полная версия

полная версияFrancis Beaumont: Dramatist

I wonder whether it may not be possible for us henceforth to give to Fletcher, and the whole Fletcherian syndicate, – the Massingers, Fields, Middletons and Rowleys, Dabornes, and the rest, – the praise and the blame for what they produced, but eliminate Beaumont from the award. One grows weary of the attribution to him of moral irresponsibilities and extravagances in art of which he was, in all that we have learned of his breeding, life, and mental habit the implicit opponent – very much like his brother Sir John, – and of the opposite of which he was in his poetic and dramatic output, as I have minutely demonstrated, the professed exponent. In the broad daylight of philological science and modern historical criticism we should no longer regard Beaumont-and-Fletcher as an indivisible pair of Siamese twins, constructing with all four hands at once the fabric of fifty-three plays, or even of ten, and tongue-and-grooving the boards with such diabolic deftness that each artisan shall for ever be credited with the merits and defects of both. It is, at any rate, time that the world of scholars, – and then the world of readers may follow, – render unto Cæsar the things that are Cæsar's.

As for Cæsar, we concede to him, John Fletcher, once for all, as he may be read in his independent work, by one even running, artistic virtues numerous and brilliant:260 gaiety, wit, sprightly dialogue; mastery of stage-craft, – of all the devices of captivating plot and rattling 'business,' and all the conventions and theatrically legitimate clap-trap of dramatic types and humours, hallowed by success, adored by the actor, and darling to the public. We concede skill in the weaving of romantic complications, captivatingly cunning, and in the construction of situations irresistibly ludicrous; remarkable inventiveness of sensational adventure and spectacular scene and attractive setting; realism at every turn, and an ability to portray manners, varied and minute. Above all, we admire, and thankfully rejoice in, his smoothness of mechanism, his lightness of touch, his contrivance and manipulation of pure comedy – whether of manners or intrigue, – and in his world of characters, not only laughter-compelling, but endowed with humour themselves and sworn to the enthronement of the Spirit of Mirth.

On the other hand we read on every page of Fletcher's independent contribution to English drama what, perhaps, was not the man himself, but his dramaturgic pose – still for the world the essence of the Fletcher who ruled it from the stage:261 we read his "shallowness of moral nature," his acquiescence in the ethical apathy and cynicism of the time; his indelicacy; his indifference to, if not irreverence for, the dramatic proprieties, – his subservience to popular taste and favour in an age when "the theatre had ceased to be the expression of patriotism and of the national life and had become the amusement of the idle gentleman and of such members of the lower classes as were not kept away by the Puritan disapproval of the stage." We witness with amusement but with self-reproach his presentation of characters superficial, and superficially refracting the evanescent vanities and heartless vices of Jacobean London, as if representative of actual and general life; his play of emotions feigned or sentimental; his violent contrasts, unnatural conversions, impossible revolutions of fortune; we discern the absence of subtle intuition, the failure to effect profound and lasting impression, the "lack of seriousness and of spiritual poise." We note, in the heroic-romantic dramas, improbability and extravagance; and, in the tragedies, such as Valentinian, a total disregard of the unity of interest, – just that muddling of motives of which the editor of The Nation has written, – and therefore the failure to realize unity of effect. There has been no moral sequence: the suspense has been distracted by the variety of emotions stirred. After the hours of strain to which the spectator has imaginatively subjected himself, the relief – what Aristotle calls the catharsis – is not forthcoming: because the intellect has not been clarified but fuddled; the will has not been braced; the feelings appropriate to tragedy – of pity and of fear – have not enjoyed an unthwarted, undiverted outflow. The faculties have been tantalized by manifold, deceptive, agonies of thirst. They should have been centred in one yearning, conducted to one clear spring of medicament, and purged by waters of truth, justice, and sympathy. From Fletcher's Valentinian and Bonduca despite the poetry and the onrush of the dramatic action there proceeds no calm, "all passion spent"; no beauty that is peace. And of the tragicomedies, The Loyall Subject and A Wife for a Month, this verdict may be even more readily pronounced.

Such are the excellences and defects of Fletcher. Let us give him all the glory of the former: but stay from burdening Beaumont, who had faults of his own, with responsibility for the latter, – with the unmorality or immorality or extravagant artistry of Fletcher when not associated with Beaumont. With the vices and virtues of Fletcher's rocket, bursting in stellar polychrome, Beaumont had nothing to do. To him justice can be accorded only if he, after these three centuries, be considered alone, – not for ever coupled with Fletcher, but spoken and thought of, and known, as dramatist, poet, man of far sounder fibre, and more virile marrow, – of superior insight, imagination, and art.

Next to Shakespeare, the most essentially poetic dramatist of the early Jacobean period was Francis Beaumont. He had not the learning of Jonson, nor the long career, nor the dictatorial position; nor did he attempt to rival him in comedy, or criticism. But his great poem, The Maides Tragedy is a thousand times more enthralling and poetic than Sejanus or Catiline. Shakespeare always excepted, the only author of tragedy in that day whose intuitions and lines of astounding splendour at all compete with, sometimes surpass, Beaumont's is Webster; but the fascination of his Duchess of Malfy is lurid, miasmatic, stupefying; that of The Maides Tragedy, breathless and heart-breaking.

In the drama of mingled motive, Jonson produced but one masterpiece that in poetry, valiancy of design, and portrayal of the ridiculous, equals Beaumont's A King and No King, – the Volpone; but that is not tragicomedy, and it drips venom. All that stands between A King and No King and artistic perfection is the dénouement. If the lovers had died, their struggle against temptation still continuing, their passion unfulfilled, – if in the moment of death, they had discovered that their union were no incest after all, Beaumont would have left behind him another consummate tragedy. As it is, to find a parallel in Jacobean literature, outside of Shakespeare, one must turn to Ford's 'Tis a Pity, She's a Whore. There again with poetic effulgence the problem of incest is dramatized; but how half-hearted the struggle, insincere the moral, – the poetry, purple and unconvincing!

In romantic comedy, between 1603 and 1625, others have produced plays which from the dramatic point of view equal Philaster, – Dekker, Heywood, Marston, Chapman, Middleton, and Rowley. Not all even of Shakespeare's romantic comedies come up to Philaster in literary or dramatic excellence; but only Shakespeare has written what surpasses it.

In the comedy that delineates humours, The Woman-Hater, as regards both poetry and technique, falls below several plays of Dekker, Chapman, Marston, Middleton, and Jonson, and below the earlier efforts of Shakespeare; but in characterization it is as good as some of Shakespeare's. There is no comic figure in Love's Labour's Lost, the Two Gentlemen of Verona, or the Comedy of Errors, that surpasses Beaumont's Hungry Courtier; and the humorous dialogue and the prose as a whole of The Woman-Hater are more natural, and more intelligible to the modern ear. With Shakespeare's later comedies that in any degree avail themselves of the 'humours' element, or with Jonson's masterpieces in this kind, The Woman-Hater, of course, can not be placed in comparison. But if for the nonce, we consider Beaumont's Knight of the Burning Pestle, merely in its 'humours' aspect, we must acknowledge that its characters are as clear-cut, as typical of the time and as provocative of laughter as those of Every Man in his Humour, which for all its historic significance most people nowadays read, or might read, with a yawn; and that it is less artificial in construction, more human in motive and character, more modern in mirth than The Silent Woman, – even though the object of its ridicule be now caviare to the general.

To set Beaumont's burlesque as a comedy of manners beside any of Shakespeare's comedies from 1594 down, would be futile, but of the early Shakespearian plays mentioned above none shakes more with fun than The Knight of the Burning Pestle, and not one gives us the flavour of London, – its citizens, their affectations and ideals, their reading, habits and life, – or of England, that the Knight affords in every scene. If Shakespeare instead of writing, say, the Comedy of Errors had written The Knight of the Burning Pestle, scholars would now be flooding us with Variorum editions of it, women's literary clubs would be likening him with fervour to Cervantes, and the public might be so well educated to its allusions and ideas that our Hebrew emperors of the theatrical world and arbiters of dramatic vogue would be "starring" it through the country to the delight of audiences that wisely make a show of understanding and enjoying everything that Shakespeare wrote. To what unrealized extent the fate of plays hangs upon the tradition of the green-room, the actor's whim, the manager's enterprise or ignorance, and luck, is material for an essay in itself. I am not asserting that The Knight of the Burning Pestle pretends to poetry, as do all of Shakespeare's plays; but that for chuckling and side-long mirth, and for manners and insight into the life of a rarely interesting period, it is fine comedy, while as burlesque it is equalled by few of the kind in our language and excelled by none.

It may be true that burlesques lose their flavour with the passing of their victims. But that does not hold true of the drama of problems perennially recurring and of emotions common to men of every age and clime. Of such drama are The Maides Tragedy and A King and No King. They are not antiquated. And I doubt whether they are stronger meat than some of Shakespeare's plays, all of which are more or less 'arranged' before they are placed upon the modern stage. As to strong meat, the difference between the Elizabethan taste and the present Georgian is more a matter of variety than of flavour. Our forefathers liked their venison in gobbets, for three hours at a stretch, and washed it down with a tun or two of sack. The theatre-going public to-day likes its game just as high, but it varies the meal with other dishes as highly seasoned, – and washes it down with a foreign-labeled little bottle of champagne. Our ancestors called a depraved woman by a brief bad name, and put it into poetry. We denominate her, if at all, by some euphemistic circumlocution, in prose; but we none the less throng the theatre to see Dalilah play, and we follow with apparent gusto her sinuous enticements upon the stage. We rejoice in problem-plays more erotic, and far more subtly perilous, than those which Shakespeare and Beaumont beheld. We are of an age of uplift, and meticulous reform. We would eliminate fornication and adultery; but not from our plays. They teem with – suggestion. There is nothing neurotic, nothing insidious in The Maides Tragedy and A King and No King. The grave of sin is wide open; and the spade that digged it stands in plain view, and is called a spade. On the whole I had rather have the Anglo-Saxon bluntness and gleaming poetry of the Beaumont than the whitewashed epigram and miching-mallecho of the twentieth-century play I saw last night. There is no reason why, properly cut and staged, Beaumont's greatest plays should not yield delight to-day. And as for the reader why should he not turn back to "the inexhaustible treasures" of entertainment offered by these plays. "They were," as says Mr. Paul Elmer More, "they were to the Elizabethan age what the novel is to ours, and I wonder how many readers three centuries from now will go back to our fiction for amusement as we to-day can go back to Beaumont and Fletcher."

I began this book by quoting from an historian of the drama of marked repute: "In the Argo of the Elizabethan drama – as it presents itself to the imagination of our own latter days – Shakespeare's is and must remain the commanding figure. Next to him sit the twin literary heroes, Beaumont and Fletcher – more or less vaguely supposed to be inseparable from one another in their works." And also from the last great poet of the Victorian age: "If a distinction must be made between the Dioscuri of English poetry, we must admit that Beaumont was the twin of heavenlier birth. Only as Pollux was on one side a demigod of diviner blood than Castor can it be said that on any side Beaumont was a poet of higher and purer genius than Fletcher; but so much must be allowed by all who have eyes and ears to discern in the fabric of their common work a distinction without a difference." If I have succeeded in showing that in the fabric of their common work the distinction between Beaumont and Fletcher is measured by a wide and clearly visible difference, I shall be happy. Others, to whom I have repeatedly expressed my indebtedness even when disagreeing with particulars of their criticism, have cleared the way. If in this book anything has been added to their services that may help the world to distinguish these two dramatists not only hand from hand but mind from mind, and to see Beaumont plain, as I see him in the long gallery of his contemporaries, I shall be happier still; but most amply rewarded if, for the future, it may be fittingly recognized not only that Beaumont was the twin of heavenlier birth – the Pollux, but why he was. Then, perhaps, the world of sagacious readers may turn from talking always of Beaumont-and-Fletcher, and protest occasionally and with well-informed reason in the name of Francis Beaumont alone.

APPENDIX

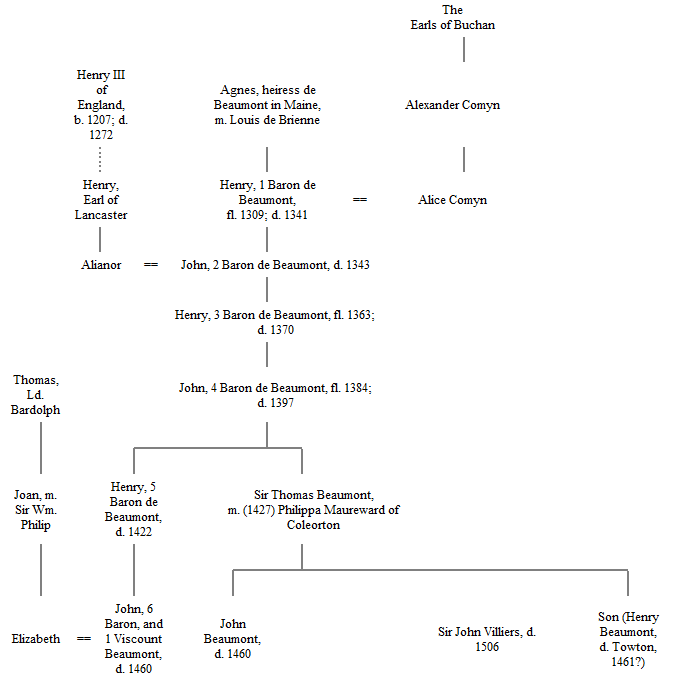

GENEALOGICAL TABLES

TABLE A.

PLANTAGENET, COMYN, BEAUMONT, AND VILLIERS

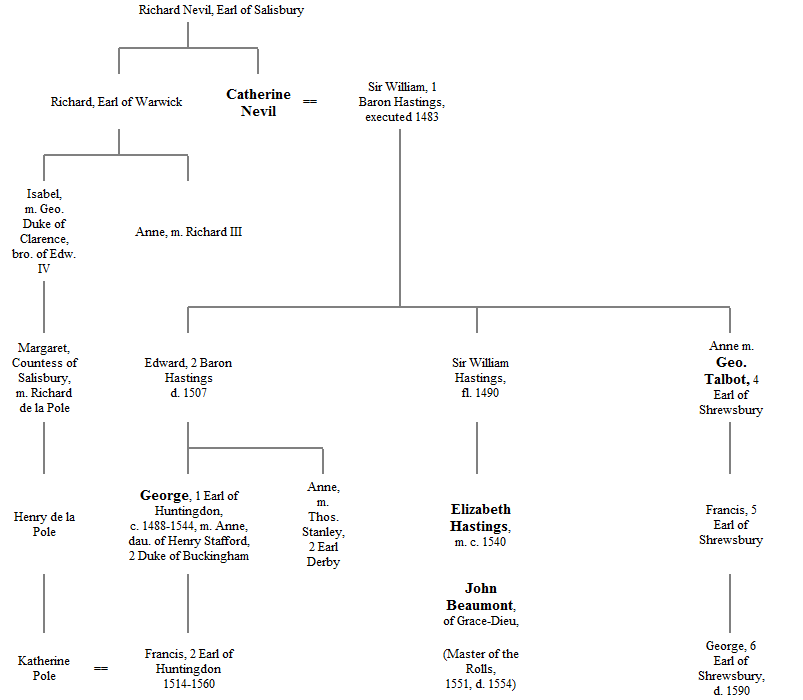

TABLE B

NEVIL, HASTINGS, BEAUMONT, TALBO

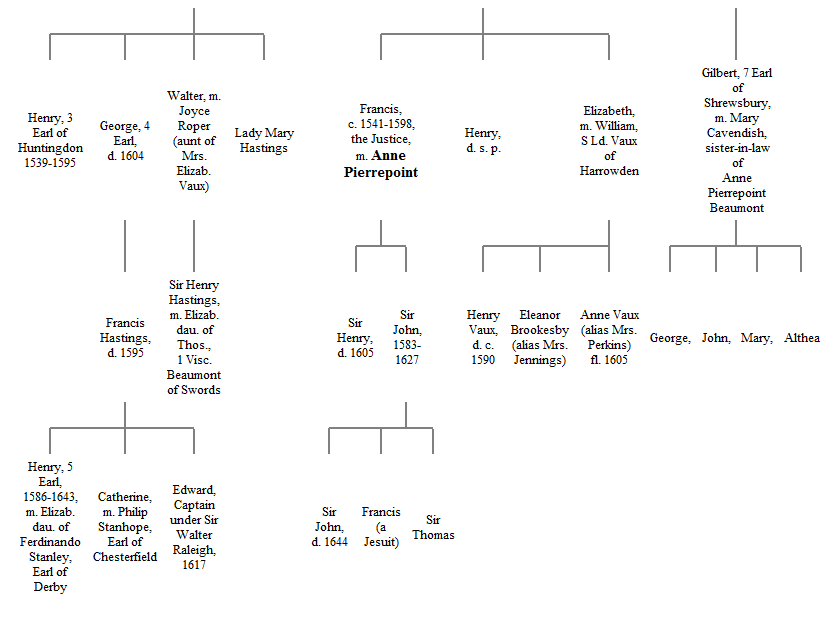

TABLE C.

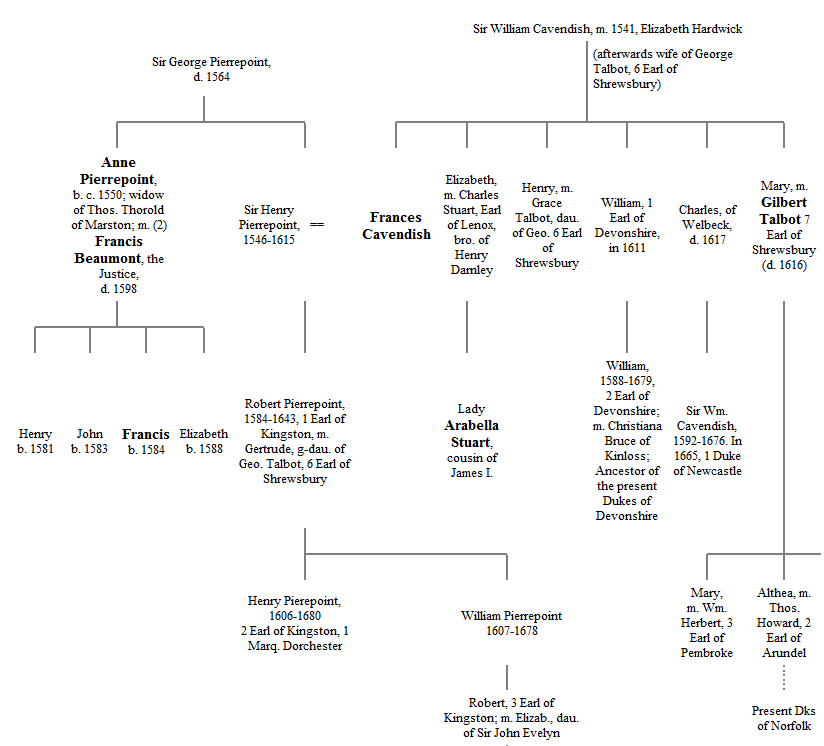

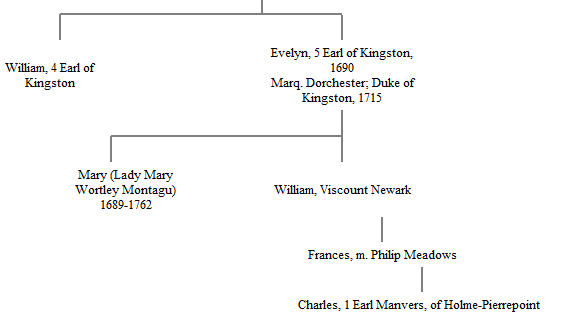

BEAUMONT. PIERREPOINT. CAVENDISH, TALBOT

TABLE D

BEAUMONT, VAUX, TRESHAM, CATESBY

TABLE E

FLETCHER, BAKER, SACKVILLE

1

Leland's Itinerary, Ed. L. T. Smith, Vol. I, 18-19.

2

Leland's Itinerary, Ed. L. T. Smith, Vol. IV, 126.

3

Collins, Peerage of England, IX, 460.

4

J. Nichols, Collections toward the History of Leicestershire (Biblioth. Topogr. Brit., VII, 534). See, below, Appendix, A.

5

Letters relating to the Suppression of the Monasteries, pp. 251-252, Camden Society, 1843. The editor, Thos. Wright, describes the petitioner as of Thringston, Co. Leicester.

6

J. M. Rigg, Dict. Nat. Biog. art., John Beaumont; and Nichols's History of Leicestershire, III, ii, 651, et seq.

7

Collins, Peerage, VI, 648, et seq.; H. N. Bell, The Huntingdon Peerage, 1821. See also, below, Appendix, Table B.

8

Calendar of State Papers (Domestic), 1595, p. 154.

9

Challoner, Missionary Priests, I, 347.

10

For the preceding details, and some of those which follow, see the respective articles in the Dictionary of National Biography; Dyce's Works of Beaumont and Fletcher, Vol. I, Biographical Memoir; Grosart, Sir John Beaumont's Poems, and the sources as indicated. See also, below, Appendix, Table C.

11

See Shaw's Knights of England; Collins, Peerage; and articles in D. N. B. under names.

12

Dyce says that the Judge was knighted; so Rigg (D. N. B.) and others. The Inner Temple Records speak of him thirty times, but only once, Nov. 5, 1581, as "Sir," though others in memoranda running to 1601 which mention him are given the title. In the codicil to his will he is plain "Mr. Beaumont"; and he is not included in Shaw's Knights of England.

13

For a Seat in the Groves of Coleorton.

14

Works of B. and F., XVI.

15

Inns of Court and Chancery (Lond., 1912), p. 45; W. R. Douthwaite, Gray's Inn, its History and Associations (Lond., 1886), pp. 36, 78, 253. For the Beaumonts, and what follows, see, also, Inderwick, Inner Temple Records (Lond. 1896), I, 421; II, 435; Introductions, and subjects as indexed.

16

Inns of Court, etc., p. 163.

17

The Dedication first appears in the folio of 1616.

18

H. E. Duke, K. C., M. P., Gray's Inn in Six Lectures on the Inns of Court and of Chancery, 1912.

19

Early English Classical Tragedies, Introduction, p. lxxxvi.

20

Letters and Life of Francis Bacon, I, 342.

21

Cunliffe, E. E. Class. Tragedies, p. lxxxvi.

22

Reprinted by Dramaticus, Sh. Soc. Pap. III, 94 (1847).

23

Dramaticus, (as above).

24

On these identifications, see Fleay, Chron. Eng. Dr., I, 143-145; Elton, Michael Drayton, pp. 13, 58; Child, Michael Drayton (in Camb. Hist. Lit., IV, 197, et seq.).

25

Gardiner, Hist. Engl. 1603-1607, p. 87.

26

Shaw's Knights of Engl., Vol. II, under dates.

27

Grosart (D. N. B. art. John Beaumont) says that John had been admitted to the Inner Temple with Henry. John does not appear in Inderwick.

28

John Morris, Life of Father John Gerard, p. 311, et seq.

29

Morris, op. cit., p. 113. See below, Appendix, Table D.

30

Gardiner, Hist. Engl. 1603-1642, I, 234.

31

Morris, p. 360. See also, below, Appendix, Table D.

32

Fletcher's connections, also, the Bakers, Lennards, and Sackvilles were interested in the fortunes of Francis Tresham; for he had married Anne Tufton of Hothfield, Kent, granddaughter of Mary Baker who was sister of Sir Richard of Sissinghurst and of Cicely, first Countess of Dorset. – Collins, III, 489; Hasted, VII, 518. See below, Appendix, Tables D, E.

33

The facts as here presented are drawn from the Calendar of State Papers (Domestic), the Gunpowder Plot Book, and Father Gerard's Narrative (in Morris), in the order of dates as indicated.

34

Nov. 5-8.

35

Morris, Life of Father Gerard, p. 385.

36

Morris, pp. 413-414.

37

Cal. State Papers (Dom.), April 7, 1593.

38

Briefe View of the State of the Church.

39

Nichols's Progresses of Queen Elizabeth, II, 506-510.

40

See the story in Camden Miscellany, III (1854).

41

Sir Richard Baker, in his Chronicle of the Kings of England.

42

Fuller's Worthies, as cited by Dyce, I, x, xi.

43

The materials as furnished by Dyce, B. and F., I, xiv-xv, from Birch's Mem. of Elizabeth, and the Bacon Papers in the Lambeth Library are confirmed by Cal. St. Papers (Dom.), June 1596, July 9, 1597, etc.

44

As her monument in Canterbury would indicate. Hasted, Hist. Kent, XI, 397.

45

For the Bakers and their connections, see Hasted, Hist. Kent, III, 77; IV, 374, et seq.; VII, 100-101; for the Sackvilles. – Hasted, III, 73-82; for the Lennards, – Hasted, III, 108-116; the Peerages of Collins, Burke, etc., and the articles in D. N. B. See also, below, Appendix, Table E.

46

The King's letter to Salisbury (undated, but of 1608). Gardiner, Hist. Engl. 1603-1642, II, 43-45.

47

This much more distinguished favour has been overlooked by Thorndike and other critics. But it is possible that Shaw, Knights of England, I, 154, may be confounding him with another Carr, a favourite of Queen Anne's.

48

Dyce, B. and F., Vol. I, p. 53.

49

Act IV, 14, 50-54.

50

Cf., Lazarillo's Farewells, Act III, 3.

51

See Chap. XXIV, below.

52

Prologue, for a revival, in 1649, of The Woman-Hater, which D'Avenant mistakenly attributes to Fletcher.

53

Reasons for dating an earlier version of the play about 1604 are given by Oliphant, Engl. Studien, XV, 338-339, and Thorndike, Infl. of B. and F., 70-71. In its present form, however, the play dates later than Jonson's Epicoene, 1610. See Gayley, Rep. Eng. Com., III, Introd., § 15.

54

I heartily concur with W. W. Greg's interpretation, Pastoral Poetry and Pastoral Drama, p. 274.

55

See Fleay, Chron. Eng. Dr., I, 312, and Thorndike, Infl. of B. and F., 64.

56

Folio, 1647, 'mortallitie'; a misprint.

57

See Chap. XXIII, below.