полная версия

полная версияCannibals all! or, Slaves without masters

But look at these unfortunates – the infant serfs of a neglected rural district! Look at them physiologically – observe their lank, colorless hair, screening the sunken eye, and trailing upon the bony neck; look at the hollow cheeks, the candle-like arms, and the unmuscular shanks which serve the young urchins for legs! But are not these children breathing a pure atmosphere? Are they not Nature's own? Yes; but there is one thing wanting to them – one ominous word clears up the mystery. Starvation! Not, indeed, such starvation as brings the sorrows of a sad lot to a speedy end; but such as drags its pining sufferings out, through the overshadowed years of childhood and youth; through those spasmodic years of manhood during which the struggle to exist wears an aspect of rugged rigor; and then through that residue of early decrepitude, haggard, bent, idiot-like, which is indeed an unblessed end of an unblessed existence. This rural population does pretty well if the father be able-bodied and sober, and the mother managing, through the summer season, of wheat-hoeing, hay-making, and wheat harvest; that is to say, when the labor of the mother and her children comes in to swell a little the weekly wages. During these weeks something of needed clothing is obtained, rent is paid up, and a pittance of animal food, weekly, is added to the bread, and the tea, and the potato of the seven months' diet.

It would be doing a wrong to our worthy farmer friends, and to the rural sporting gentry, to affirm that these miserables are actually dying of want. No, they are not dying, so as inquests must be held before they may be buried – would to God they were – they are the living – they are living to show what extremities men, women and children may endure, and yet not die; or what they hold to be worse, not to betake themselves to "the union!" But how do these same men, women and children pass five months of the year? Gladly would one find them curled round like hedgehogs, and hybernating in hollow trees; in rabbit burrows, lost to consciousness. We should, indeed, count it a miracle if, on a May morning, we were to see a group of human beings start up alive from the sward, along with the paiglus and the cowslips. But it is much less than a miracle to see the people of a depressed rural district stepping alive out of the winter months!

The instances are extremely rare in which those who were born to the soil, and destined to the plow, rise above their native level. Such instances – two, three, or five – might be hunted up, if an agricultural county were ransacked for the purpose; but the agricultural laborer, even if he had the brain and the ambition requisite, and if otherwise he could effect it, would seldom bring with him that which the social mass, into which he might rise, especially needs, namely, a fully developed and robust body. Meantime, what is it that is taking place in hundreds of instances, and every day, throughout the entire area of the manufacturing region? Men, well put together, and with plenty of bone, and nerve, and brain, using with an intense ardor those opportunities of advancement which abound in these spheres of enterprise and of prosperous achievement – such men are found to be making themselves heard of among their betters, are seen well-dressed before they reconcile themselves to the wearing of gloves; by rapid advances they are winning for themselves a place in society – a place which, indeed, they well deserve; and there they are doing what they had not thought of – they are regenerating the mass within which they have been received.

We extract the following from an article in the Edinburgh Review on Juvenile and Female Labor, in its January No., 1844. It is of the highest authority, being part of a report of commissioners appointed by Parliament, and stands endorsed as well by the action of Parliament as by the authority of the Reviewer:

Our limits will not allow us to go through all the employments reported upon in these volumes; but, as specimens, we will give a short account of the condition of the people engaged in Coal mines, Calico-printing, Metal wares, Lace-making, and Millinery.

Coal Mines.– The number of children and young persons employed in these mines is enormous; and they appear to commence working, even underground, at an earlier age than is recorded of any other occupation except lace-making. The Commissioners report —

"That instances occur in which children are taken into these mines to work as early as four years of age, sometimes at five, not unfrequently between six and seven, and often from seven to eight, while from eight to nine is the ordinary age at which their employment commences… That a very large proportion of the persons employed in these mines is under thirteen years of age; and a still larger proportion between thirteen and eighteen. That in several districts female children begin to work in the mines as early as males.

"That the nature of the employment which is assigned to the youngest children, generally that of 'trapping,' requires that they should be in the pit as soon as the work of the day commences, and, according to the present system, that they should not leave the pit before the work of the day is at an end.

"That although this employment scarcely deserves the name of labor, yet, as the children engaged in it are commonly excluded from light, and are always without companions, it would, were it not for the passing and re-passing of the coal carriages, amount to solitary confinement of the worst order.

"That in some districts they remain in solitude and darkness during the whole time they are in the pit, and, according to their own account, many of them never see the light of day for weeks together during the greater part of the winter season, excepting on those days in the week when work is not going on, and on the Sundays.

"That at different ages, from six years old and upwards, the hard work of pushing and dragging the carriages of coal from the workings to the main ways or to the foot of the shaft, begins: a labor which all classes of witnesses concur in stating, requires the unremitting exertion of all the physical power which the young workers possess.

"That, in the districts in which females are taken down into the coal mines, both sexes are employed together in precisely the same kind of labor, and work for the same number of hours; that the girls and boys, and the young men and the young women, and even married women and women with child, commonly work almost naked, and the men, in many mines, quite naked; and that all classes of witnesses bear testimony to the demoralizing influence of the employment of females underground.32

"That, in the east of Scotland, a much larger proportion of children and young persons are employed in these mines than in other districts, many of whom are girls; and that the chief part of their labor consists in carrying the coals on their backs up steep ladders.

"That when the work-people are in full employment, the regular hours of work for children and young persons are rarely less than eleven; more often they are twelve; in some districts they are thirteen; and in one district they are generally fourteen and upwards.

"That, in the great majority of these mines night-work is a part of the ordinary system of labor, more or less regularly carried on according to the demand for coals, and one which the whole body of evidence shows to act most injuriously both on the physical and moral condition of the work-people, and more especially on that of the children and young persons.

"That in many cases the children and young persons have little cause of complaint in regard to the treatment they receive, while in many mines the conduct of the adult colliers to them is harsh and cruel; the persons in authority who must be cognizant of this ill usage never interfering to prevent it, and some of them distinctly stating that they do not conceive they have a right to do so. That with some exceptions little interest is taken by the coal-owners in the children employed in their works after the daily labor is over… That in all the coalfields accidents of a fearful nature are extremely frequent, and of the work-people who perish by such accidents, the proportion of children and young persons sometimes equals, and rarely falls much below that of adults." – (First Report, p. 255-7.)

With respect to the general healthiness of the employment, there is considerable discrepancy in the evidence adduced; many witnesses stating that the colliers generally, especially the adults, are a remarkably healthy race, showing a very small average of sickness,33 and recovering with unusual rapidity from the severest accidents; – a peculiarity which the medical men reasonably enough attribute to the uniform temperature of the mines, and still more to the abundance of nutritious food which the high wages of the work-people enable them to procure. The great majority of the witnesses, however, give a very different impression. Upwards of two hundred, whose testimony is quoted, or referred to in the Report of the Central Commissioners, testify to the extreme fatigue of the children when they return home at night, and to the injurious effect which this ultimately produces on their constitution.

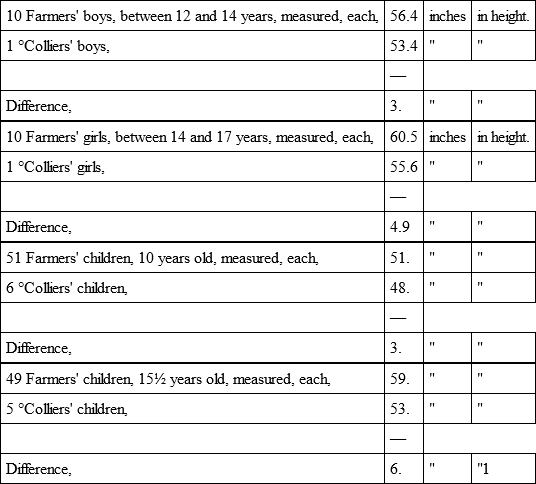

While the effect of such early and severe labor is, to cause a peculiar and extraordinary degree of muscular development in collier children, it also stunts their growth, and produces a proportionate diminution of stature, as is shown by the following comparison. – (Physical and Moral Condition of Children, p. 55.)

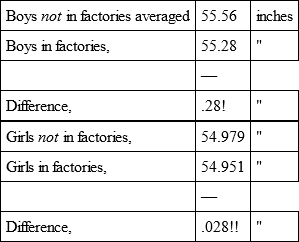

1. It is curious to contrast this with a similar comparison instituted by the Factory Commissioners, and embracing upwards of 1000 children. – (Analysis of the Evidence taken before the Factory Commissioners, p. 9.)

Labor in coal mines is also stated, by a great number of most respectable witnesses, to produce a crippled gait, and a curvature of the spinal column, as well as a variety of disorders – among which may be enumerated, affections of the heart, rupture, asthma, rheumatism, and loss of appetite; – and this not merely in a few cases, but as an habitual, and almost inevitable result of their occupation.

"Of the effect of employment in the coal mines of the East of Scotland in producing an early and irreparable deterioration of the physical condition, the Sub-commissioner thus reports: – 'In a state of society, such as has been described, the condition of the children may be easily imagined, and its baneful influence on the health cannot well be exaggerated; and I am informed by very competent authorities, that six months' labor in the mines is sufficient to effect a very visible change in the physical condition of the children: and indeed it is scarcely possible to conceive of circumstances more calculated to sow the seeds of future disease, and, to borrow the language of the instructions, to prevent the organs from being developed, to enfeeble and disorder their functions, and to subject the whole system to injury, which cannot be repaired at any subsequent stage of life.' – (Frank's Report, s. 68: App. Pt. I, p. 396.) In the West of Scotland, Dr. Thomson, Ayr, says: – 'A collier at fifty generally has the appearance of a man ten years older than he is.'" – (Evidence, No. 34; App. Pt. I, p. 371, l. 58.)

If we turn to the testimony as to the moral, intellectual, and spiritual state of the great mass of the collier population, the picture is even darker and more appalling than that which has been drawn of their physical condition. The means of instruction to which they have access are scanty in the extreme; – their readiness to avail themselves of such means, if possible still scantier; and the real results of the instruction they do obtain, scantiest of all – as the following extracts will show: —

"As an example of the mental culture of the collier children in the neighborhood of Halifax, the Sub-commissioner states, that an examination of 219 children and young persons at the bottom of one of the coal-pits, he found only 31 that could read an easy book, not more than 15 that could write their names, these latter having received instruction at some day-school before they commenced colliery labor, and that the whole of the remaining number were incapable of connecting two syllables together." – (Scriven, Report, Mines: App. Pt. II, 73, s. 91.)

"Of the state of education in the coalfields of Lancashire, the Sub-commissioner gives the following account: – 'It was my intention to have laid before the Central Board evidence of the effects of education, as shown by the comparative value of educated and uneducated colliers and children employed in coal mines, as workmen, and to have traced its effects, as shown by the superior moral habits and generally more exalted condition of those who had received the benefits of education over those who had not, which I had observed and proved to exist in other branches of industry. I found, however that the case was hopeless; there were so few, either of colliers or their children, who had even received the first rudiments of education, that it was impossible to institute a comparison.' – (Kennedy, Report, Mines: App. Pt. II, p. 183, s. 268.)

"In the coalfields of North Lancashire examined by Mr. Austin, it is stated that the education of the working-people has been almost wholly neglected; that they have received scarcely any instruction at all, either religious or secular; that they cannot therefore be supposed to have any correct conception of their moral duties, and that in fact their intellects are as little enlightened as their places of work – 'darkness reigns throughout.' – (Report, Mines: App. Pt. II, p. 805, s. 26.)

"In the East of Scotland a marked inferiority in the collier children to those of the town and manufacturing population. Upwards of 100 heads of collier families, most of whom leave their children to themselves – to ignorance and irreligion." – (Ibid. p. 426, l. 42.) 'Many of the children are not educated at all.'" – (Ibid. p. 428, l. 30.)

It appears that, in the principal mining districts, few of the colliers attend any place of worship; and of their entire ignorance of the most elementary truths, either of secular or religious knowledge, the following extracts will give some idea: —

"Yorkshire. – With respect even to the common truths of Christianity and facts of Scripture,' says Mr. Symons, 'I am confident that a majority are in a state of heathen ignorance. I unhesitatingly affirm that the mining children, as a body, are growing up in a state of absolute and appalling ignorance; and I am sure that the evidence I herewith transmit, alike from all classes – clergymen, magistrates, masters, men, and children – will fully substantiate and justify the strength of the expressions which I have alone felt to be adequate to characterize the mental condition of this benighted community.'

"'Throughout the whole district of the coal-field,' says Mr. Scriven, 'the youthful population is in a state of profaneness, and almost of mental imbecility.'

"'The ignorance and the degraded state of the colliers and their children,' says Mr. Kennedy, 'are proverbial throughout this district. They are uneducated, ignorant, and brutal; deteriorated as workmen and dangerous as subjects.'"

But nothing can show their mental state in so striking a manner, as the evidence derived from the examination of the children themselves, by the Sub-commissioner: —

"'A girl eighteen years old – I never learnt nought. I never go to church or chapel. I have never heard that a good man came into the world, who was God's Son, to save sinners. I never heard of Christ at all. Nobody has ever told me about him, nor have my father and mother ever taught me to pray. I know no prayer: I never pray. I have been taught nothing about such things.' – (Evidence, Mines, p. 252, 11, 35, 39.) 'The Lord sent Adam and Eve on earth to save sinners.' – (Ibid. p. 245, l. 66.) 'I don't know who made the world; I never heard about God.' – (Ibid. p. 228, l. 17.) 'Jesus Christ was a shepherd; he came a hundred years ago to receive sin. I don't know who the Apostles were.' – (Ibid. p. 232, l. 11.) 'Jesus Christ was born in heaven, but I don't know what happened to him; he came on earth to commit sin. Yes; to commit sin. Scotland is a country, but I don't know where it is. I never heard of France.' – (Ibid. p. 265, l. 17.) 'I don't know who Jesus Christ was; I never saw him, but I've seen Foster, who prays about him.' – (Ibid. p. 291, l. 63.) 'I have been three years at a Sunday-school. I don't know who the Apostles were. Jesus Christ died for his son to be saved.' – (Ibid. 245, l. 10.) Employer (to the Commissioner,) 'You have expressed surprise at Thomas Mitchell (the preceding witness) not having heard of God. I judge there are few colliers hereabouts that have.'" – (Second Report, p. 156.)

The moral state of the collier population is represented by the Sub-commissioners as deplorable in the extreme: —

"Lancashire. – 'All that I have seen myself,' says the Sub-commissioner, 'tends to the same conclusion as the preceding evidence; namely, that the moral condition of the colliers and their children in this district, is decidedly amongst the lowest of any portion of the working-classes.' – (Ibid. Report, s. 278, et seq.)

"Durham and Northumberland. – The religious and moral condition of the children, and more particularly of the young persons employed in the collieries of North Durham and Northumberland, is stated by clergymen and others, witnesses, to be 'deplorable.' 'Their morals,' they say, 'are bad, their education worse, their intellect very much debased, and their carelessness, irreligion, and immorality' exceeding any thing to be found in an agricultural district." – (Leifchild, Report, Mines: Evidence, Nos. 795, 530, 500, 493, 668.)

Calico-Printing.– This employs a vast number of children of both sexes, who have to mix and grind the colors for the adult work-people, and are commonly called teerers. They begin to work, according to the Report, sometimes before five years of age, often between five and six, and generally before nine. The usual hours of labor are twelve, including meal-time; but as the children generally work the same time as the adults, "it is by no means uncommon in all the districts for children of five or six years old to be kept at work fourteen and even sixteen hours consecutively." – (Second Report, p. 59.) In many instances, however, it will be seen that even these hours are shamefully exceeded, during a press of work.

"352. Thomas Sidbread, block-printer, after taking a child who had already been at work all day to assist him as a teerer through the night, says – 'We began to work between eight and nine o'clock on the Wednesday night; but the boy had been sweeping the shop from Wednesday morning. You will scarcely believe it, but it is true – I never left the shop till six o'clock on the Saturday morning; and I had never stopped working all that time, excepting for an hour or two, and that boy with me all the time. I was knocked up, and the boy was almost insensible.'

"353. Henry Richardson, block-printer, states – 'At four o'clock I began to work, and worked all that day, all the next night, and until ten the following day. I had only one teerer dining that time, and I dare say he would be about twelve years old. I had to shout to him towards the second night, as he got sleepy. I had one of my own children, about ten years old, who was a teerer. He worked with me at Messrs. Wilson & Crichton's, at Blakely. We began to work together about two or three in the morning, and left off at four or five in the afternoon.'

Night-work, too, with all its evil consequences, is very common in this trade; – and of the general state of education among the block-printers in Lancashire, the Commissioners thus speak, (p. 172.)

"The evidence collected by Mr. Kennedy in the Lancashire district, tends to show that the children employed in this occupation are excluded from the opportunities of education; that this necessarily contributes to the growth of an ignorant and vicious population; that the facility of obtaining early employment for children in print-fields empties the day-schools; that parents without hesitation sacrifice the future welfare of their children through life for the immediate advantage or gratification obtained by the additional pittance derived from the child's earnings, and that they imagine, or pretend, that they do not neglect their children's education if they send them to Sunday-schools."

Metal Wares.– The chief seats of manufactures in metal are Birmingham, Wolverhampton, and Sheffield; but many of the minor branches are carried on in different parts of Scotland, and in Worcestershire and Lancashire. In the various departments of this species of manufacture many thousands of children of both sexes are employed. They begin to work generally about their eighth year, as in Birmingham and Sheffield, but often earlier; while in pin-making, as carried on at Warrington, both boys and girls commence when five years old, and work twelve hours a-day, and sometimes, though rarely, even more. The hours of work in most of the metal manufactures are very irregular, generally from ten to thirteen a-day; but, especially in the neighborhood of Wolverhampton, it is by no means unfrequent to extend them to fifteen or sixteen for weeks together. The places in which the occupations are carried on are occasionally large, clean, and well ventilated; but in the great majority of cases, a very different description of them is given.

"In general the buildings are very old, and many of them are in a dilapidated, ruinous, and even dangerous condition. Nothing is more common than to find many of the windows broken; in some cases I observed more broken than whole panes; great and just complaint is made upon this point by those employed. The shops are often dark and narrow; many of them, especially those used for stamping, are from four to seven feet below the level of the ground; these latter, which are cold and damp, are justly complained of by the workers. From defective construction all these old shops are liable to become 'sufficatingly hot in summer (and also at night when the gas is lighted) and very cold in winter. Efficient ventilation is a thing unknown in these places. The great majority of the shops are never whitewashed, but there are many creditable exceptions to this statement.'

"It has been already stated, that although the whole population of the town of Wolverhampton and the neighborhood, of all ranks, are engaged in the different manufactures of the place, yet that there are few manufactories of large size, the work being commonly carried on in small workshops. Those workshops are usually situated at the backs of the houses, there being very few in the front of a street; so that the places where the children and the great body of the operatives are employed are completely out of sight, in narrow courts, unpaved yards, and blind alleys. In the smaller and dirtier streets of the town, in which the poorest of the working classes reside, 'there are narrow passages, at intervals of every eight or ten houses, and sometimes at every third or fourth house. These narrow passages are also the general gutter, which is by no means always confined to one side, but often streaming all over the passage. Having made your way through the passage, you find yourself in a space varying in size with the number of houses, hutches, or hovels it contains. They are nearly all proportionately crowded. Out of this space there are other narrow passages, sometimes leading to other similar hovels. The workshops and houses are mostly built on a little elevation sloping towards the passage.'" – (Second Report, p. 33.)

The most painful portions, however, of the Report on the metal manufactures, are those which relate to the treatment of the children and apprentices at Willenhall, near Wolverhampton, and to the noxious influences of those departments which are carried on at Sheffield. – (P. 83.)

"455. The district which requires special notice on account of the general and almost incredible abuse of the children, is that of Wolverhampton and the neighborhood. In the town of Wolverhampton itself, among the large masters children are not punished with severity, and in some of the trades, as among the japanners, they are not beaten at all; but, on the other hand, in the nail and tip manufactories, in some of the founderies, and among the very numerous class of small masters generally, the punishments are harsh and cruel; and in some cases they can only be designated as ferocious.