полная версия

полная версияThe Comstock Club

"How do you manage about your cooking?" queried the Professor.

"We have a Chinaman, who is a daisy. He is cook, housekeeper, chambermaid, and would be companion and musician if we could stand it. You must come up and see us."

"I will come to-morrow evening," Alex replied, eagerly.

"So will I," said the Colonel, with a positiveness that was noticeable.

"And so will I," shouted the Professor.

Just then the eleven o'clock whistles sounded up and down the lead. "That is our signal for retiring," said Wright, "and so good night."

"Let us go out and take a night cap, first," said the Colonel.

"Well, if I must," said Wright. "Though the rule of our Club is only a little for medicine."

The night caps were ordered and swallowed. Then the men separated, the Colonel, Professor and Wright going home, the journalist to his work.

Professor Stoneman was a character. Tall and spare, with such an outline as Abraham Lincoln had. He was fifty years of age, with grave and serene face when in repose, and with the mien of one of the faculty of a university. Still he had that nature which caused him when a boy to run away from his Indiana home to the Mexican war, and he fought through all that long day at Buena Vista, a lad of eighteen years. Of course he was with the first to reach California. He had tried mining and many other things, but the deeper side of his nature was to pursue the sciences – the lighter to mingle with good fellows. He would tell a story one moment and the next would combat a scientific theory with the most learned of the Eastern scientists, and carry away from the controversy the full respect of his opponent. There was a great fund of merriment within him, and his generosity not only kept his bank account a minus number, but moreover, kept his heart aching that he had no more to give. When by himself he was an incessant student, and beside knowing all that the books taught, he had his own ideas of their correctness, especially those that deal with the formation of ore deposits. He was a learned writer, a gifted lecturer and an expert of mines, and, over all, the most genial of men.

Adrian Wright was of another stamp altogether. He was tall and strong, with large feet and hands, a massive man in all respects, and forty-five years of age.

He had a cool and brave gray eye, a firm, strong mouth, very light brown hair and carried always with him a something which first impressed those who saw him with his power, while a second look gave the thought that beside the power which was visible, he had unmeasured reserves of concealed force which he could call upon on demand.

He went an uncultured lad to California. He was at first a placer miner. Obtaining a good deal of money he became a mountain trader and the owner of a ditch, which supplied some hydraulic grounds. He was brusque in his address, said "whar" and "thar," but his head was large and firmly poised; his heart was warm as a child's, and he was loved for his clear, good sense and for the sterling manhood which was apparent in all his ways. Though uncultured in the schools, he had read a great deal, and, mixing much with men, his judgment had matured, until in his mountain hamlet his word had become an authority.

His friends persuaded him to become a candidate for the State Legislature. After he had consented to run he spent a good deal of money in the campaign. He was elected and went to Sacramento. There he was persuaded to buy largely of Comstock stocks. He bought on a margin. When it came time to put up more money he could not without borrowing. He would not do that through fear that he could not pay. He lost the stocks. He went home in the spring to find that his clerks had given large credits to miners; the hydraulic mines ceased to pay, which rendered his ditch property valueless, and a few days later his store burned down. When his debts were paid he had but a few hundred dollars left. He said nothing about his reverses, but went to Virginia City and for several years had been working in the mines.

As already said, a miners' mess had been formed. Seven miners on the Comstock might be picked out who would pretty nearly represent the whole world.

This band had been drawn together partly because of certain traits that they possessed in common, though they were each distinctly different from all the others.

We have read of Wright. Of the others, James Brewster, was the eldest of the company. He was fifty years of age, and from Massachusetts. He was not tall, but was large and powerful.

There were streaks of gray in his hair, but his eyes were clear, and black as midnight. He had a bold nose and invincible mouth; the expression of his whole face was that of a resolute, self-contained, but kindly nature. All his movements were quick and positive.

He was educated, and though of retiring ways, when he talked everybody near him listened. He was not a miner, but a mechanical engineer, and his work was the running of power drills in the mine. He never talked much of his own affairs, but it was understood that misfortune in business had caused him to seek the West somewhat late in life. The truth was he had never been rich. He possessed a moderately prosperous business until a long illness came to his wife, and when the depression which followed the reaction from the war and the contraction of the currency fell upon the North, he found he had little left, and so sought a new field.

He was the Nestor of the Club and was exceedingly loved by his companions.

Miller, who first proposed the Club, was a New Yorker by birth, a man forty-five years of age, medium height, keen gray eyes, a clear-cut, sharp face, slight of build, but all nerve and muscle, and lithe as a panther. He had been for a quarter of a century on the west coast, and knew it well from British Columbia to Mexico, and from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific.

He was given a good education in his youth; he had mingled with all sorts of men and been engaged in all kinds of business. There was a perpetual flash to his eyes, and a restlessness upon him which made him uneasy if restrained at all. He had the reputation of being inclined to take desperate chances sometimes, but was honorable, thoroughly, and generous to a fault.

He had studied men closely, and of Nature's great book he was a constant reader. He knew the voices of the forests and of the streams; he had a theory that the world was but a huge animal; that if we were but wise enough to understand, we should hear from Nature's own voices the story of the world and hear revealed all her profound secrets.

He possessed a magnetism which drew friends to him everywhere. His hair was still unstreaked with gray, but his face was care-worn, like that of one who had been dissipated or who had suffered many disappointments.

Carlin was twenty-eight years of age, long of limb, angular, gruff, but hearty; quick, sharp and shrewd, but free-handed and generally in the best of humors. He was an Illinois man, and a good type of the men of the Old West.

His eyes were brown, his hair chestnut; erect, he was six feet in height, but seated, there seemed to be no place for his hands and hardly room enough for his feet. He was well-educated, and had been but three and a half years on the Comstock.

All the Californians in the Club insisted, of course, that there was no other place but that, but this Carlin always vehemently denied, for he came from the State of Lincoln and Douglas, and the State, moreover, that had Chicago in one corner of it, and he did not believe there was another such State in all the Republic.

Ashley was from Pennsylvania; a young man of twenty-five, above medium height, compact as a tiger in his make-up, and weighing, perhaps, one hundred and eighty pounds. His eyes were gray, his hair brown, his face almost classic in its outlines; his feet and hands were particularly small and finely formed, and there was a jollity and heartiness about his laugh which was contagious. He had an excellent education, and had seen a good deal of business in his early manhood.

Corrigan was a thorough Irishman, generous, warm-hearted, witty, sociable, brave to recklessness, curly-haired, with laughing, blue eyes; the most open and frank of faces that was ever smiling, powerfully built and ready at a moment's notice to fight anyone or give anyone his purse.

Everybody knew and liked him, and he liked everybody that, as he expressed it, was worth the liking.

He had come to America a lad of ten. He lived for twelve years in New York City, attended the schools, and was in his last year in the High School when, for some wild freak, he had been expelled. He worked two years in a Lake Superior copper mine, then went to California and worked there until lured to Nevada by the silver mines, and had been on the Comstock five years when the Club was formed.

Harding was the boy of the company, only twenty-two years of age, a native California lad. But he was hardly a type of his State.

His eyes were that shade of gray which looks black in the night; his hair was auburn. He had a splendid form, though not quite filled out; his head was a sovereign one.

But he was reticent almost to seriousness, and it was in this respect that he did not seem quite like a California boy. There was a reason for it. He was the son of an Argonaut who had been reckless in business and most indulgent to his boy. He had a big farm near Los Angeles, and shares in mines all over the coast. The boy had grown up half on the farm and half in the city. He was an adept in his studies; he was just as much an adept when it came to riding a wild horse.

He had gained a good education and was just entering the senior class in college when his father suddenly died. He mourned for him exceedingly, and when his affairs were investigated it was found there was a mortgage on the old home.

He believed there was a future for the land. So he made an arrangement to meet the interest on the mortgage annually, then went to San Francisco, obtained an order for employment on a Comstock superintendent, went at once to Virginia City and took up his regular labor as a miner. He had been thus employed for a year when the Club was formed.

This was the company that had formed a mess. Miller had worked up the scheme.

It had been left to Miller to prepare the house – to buy the necessary materials for beginning housekeeping, like procuring the dishes, knives and forks and spoons, and benches or cheap chairs, for the dining room, and it was agreed to begin on the next pay day.

CHAPTER II

About four o'clock in the afternoon of the day appointed for commencing housekeeping, our miners gathered at this new home. The provisions, bedding and chairs had been sent in advance, in care of Miller, who had remained above ground that day, in order to have things in apple-pie shape. The chairs were typical of the men. Brewster's was a common, old-fashioned, flag-bottomed affair, worth about three dollars. Carlin and Wright each had comfortable armchairs; Ashley and Harding had neat office chairs, while Miller and Corrigan each had heavy upholstered armchairs, which cost sixty dollars each.

When all laughed at Brewster's chair, he merely answered that it would do, and when Miller and Corrigan were asked what on earth they had purchased such out-of-place furniture for, to put in a miner's cabin, Miller answered: "I got trusted and didn't want to make a bill for nothing," and Corrigan said: "To tell the truth, I was not over-much posted on this furniture business, I did not want to invest in too chape an article, so I ordered the best in the thavin' establishment, because you know a good article is always chape, no matter what the cost may be."

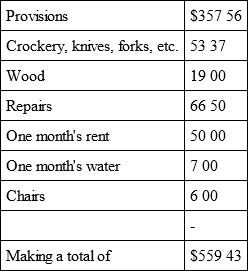

The next thing in order was to compare the bills for provisions. Brewster drew his bill from his pocket and read as follows: Twenty pounds bacon, $7.50; forty pounds potatoes, $1.60; ten pounds coffee, $3.75; one sack flour, $4.00; cream tartar and salaratus, $1.00; ten pounds sugar, $2.75; pepper, salt and mustard, $1.50; ten pounds prunes, $2.50; one bottle XXX for medicine, $2.00; total, $32.60.

The bill was receipted. The bills of Wright and Harding each comprised about the same list, and amounted to about the same sum. They, too, were receipted. The funny features were that each one had purchased nearly similar articles, and the last item on each of the bills was a charge of $2.00 for medicine. It had been agreed that no liquor should be bought except for medicine.

The bills of Carlin and Ashley were not different in variety, but each had purchased in larger quantities, so that those bills footed up about $45 each. On each of the bills, too, was an item of $4.75 for demijohn and "half gallon of whisky for medicine." All were receipted.

Corrigan's bill amounted to $73, including one-half gallon of whisky and one bottle of brandy "for medicine," and his too was receipted.

Miller read last. His bill had a little more variety, and amounted to $97.16. The last item was: "To demijohn and one gallon whisky for medicine, $8.00." On this bill was a credit for $30.00.

A general laugh followed the reading of these bills. The variety expected was hardly realized, as Corrigan remarked: "The bills lacked somewhat in versatility, but there was no doubt about there being plenty of food of the kind and no end to the medicine."

When the laugh had subsided, Brewster said: "Miller estimated that our provisions would not cost to exceed $15.00 per month apiece. I tried to be reasonable and bought about enough for two months, but here we have a ship load. Why did you buy out a store, Miller?"

"I had to make a bill and I did not want the grocery man to think we were paupers," retorted Miller.

"How much were the repairs on the house, Miller?" asked Carlin.

"There's the beggar's bill. It's a dead swindle, and I told him so. He ought to have been a plumber. He had by the Eternal. He has no more conscience than a police judge. Here's the scoundrel's bill," said Miller, excitedly, as he proceeded to read the following:

"'To repairing roof, $17.50; twenty battens, $4.00; to putting on battens, $3.00; hanging one door, $3.50; six lights glass, $3.00; setting same, $3.00; lumber, $4.80; putting up bunks, $27.50; total, $66.30.'

"The man is no better than a thief; if he is, I'm a sinner."

"You bought some dishes, did you not, Miller?" inquired Ashley. "How much did they amount to?"

"There's another scalper," answered Miller, warmly. "I told him we wanted a few dishes, knives, forks, etc. – just enough for seven men to cabin with – and here is the bill. It foots up $63.37. A bill for wood also amounts to $15.00; two extra chairs, $6.00."

Brewster, who had been making a memorandum, spoke up and said: "If I have made no error the account stands as follows:

Or, in round numbers, eighty dollars per capita for us all. I settled my account at the store, amounting to $32.60, which leaves $47.40 as my proportion of the balance. Here is the money."

This was like Brewster. Some of the others settled and a part begged-off until next pay-day.

The next question was about the cooking. After a brief debate it was determined that all would join in getting up the first supper. So one rushed to a convenient butcher shop and soon returned with a basket full of porter house steaks, sweetbreads and lamb chops; another prepared the potatoes and put them in the oven; another attended to the fire; another to setting the table. Brewster was delegated to make the coffee. To Corrigan was ascribed the task of cooking the meats, while Miller volunteered to make some biscuits that would "touch their hearts."

He mixed the ingredients in the usual way and thoroughly kneaded the dough. He then, with the big portion of a whisky bottle for a rolling-pin, rolled the dough out about a fourth of an inch thick. He then touched it gently all over with half melted butter; rolled the thin sheet into a large roll; then with the bottle reduced this again to the required thickness for biscuits, and, with a tumbler, cut them out. His biscuit trick he had learned from an old Hungarian, who, for a couple of seasons, had been his mining partner. It is an art which many a fine lady would be glad to know. The result is a biscuit which melts like cream in the mouth – like a fair woman's smile on a hungry eye. Corrigan had his sweetbreads frying, and when the biscuits were put in the oven, the steak and chops were put on to broil. The steak had been salted and peppered – miner's fashion – and over it slices of bacon, cut thin as wafers, had been laid. The bacon, under the heat, shriveled up and rolled off into the fire, but not until the flavor had been given to the steak. One of the miners had opened a couple of cans of preserved pine-apples; the coffee was hot, the meats and the biscuits were ready, and so the simple supper was served. Harding had placed the chairs; Brewster's was at the head of the table.

Corrigan waited until all the others had taken their seats at the table; then, with a glass in his hand and a demijohn thrown over his right elbow, he stepped forward and said:

"To didicate the house, and also as a medicine, I prescribe for aitch patient forty drops."

Each took his medicine resignedly, and as the last one returned the glass, Corrigan added: "It appears to me I am not faling ony too well meself," and either as a remedy or preventive, he took some of the medicine.

The supper was ravenously swallowed by the men, who for months had eaten nothing but miners' boarding-house fare. With one voice they declared that it was the first real meal they had eaten for weeks, and over their coffee they drank long life to housekeeping and confusion to boarding-houses.

When the supper was over and the things put away, the pipes were lighted. By this time the shadow of Mount Davidson around them had melted into the gloom of the night, and for the first time in months these men settled themselves down to spend an evening at home. It was a new experience.

"It is just splendid," cried Wright. "No beer, no billiards, no painted nymphs, no chance for a row. We have been sorry fools for months – for years, for that matter – or we would have opened business at this stand long ago."

"We have, indeed," said Ashley. "To-night we make a new departure. What shall we call our mess?"

Many names were suggested, but finally "The Comstock Club" was proposed and nominated by acclamation.

It was agreed, too, that no other members, except honorary members, should be admitted, and no politics talked. Then the conversation became general, and later, confidential; and each member of the Club uncovered a little his heart and his hopes.

Miller meant, so soon as he "made a little stake," to go down to San Francisco and assault the stock sharps right in their Pine and California street dens. He believed he had discovered the rule which could reduce stock speculation to an exact science, and he was anxious for the opportunity which a little capital would afford, "to show those sharpers at the Bay a trick or two, which they had never yet 'dropped on.'" He added, patronizingly: "I will loan you all so much money, by and by, that each of you will have enough to start a bank."

"I shtarted a bank alridy, all be mesilf, night before last," said Corrigan.

"What kind of a bank was it, Barney?" asked Harding.

"One of King Pharo's. I put a twenty-dollar pace upon the Quane; that shtarted the bank. The chap on the other side of the table commenced to pay out the pictures, and the Quane – "

"Well, what of the Queen, Barney?" asked Carlin.

"She fill down be the side of the sardane box, and the chap raked in me double agle."

"How do you like that style of banking, Barney?" asked Ashley.

"Oh! Its mighty plisant and enthertainin', of course; the business sames to be thransacted with a grate dale of promptness and dispatch; the only drawback seems to be that the rates of ixchange are purty high."

Tom Carlin knew of a great farm, a store, a flour mill, and a hazel-eyed girl back in Illinois. He coveted them all, but was determined to possess the girl anyway.

After a little persuasion, he showed her picture to the Club. They all praised it warmly, and Corrigan declared she was a daisy. In a neat hand on the bottom of the picture was written: "With love, Susie Richards." Carlin always referred to her as "Susie Dick."

Harding, upon being rallied, explained that his father came with the Argonauts to the West; that he was brilliant, but over-generous; that he had lived fast and with his purse open to every one, and had died while yet in his prime, leaving an encumbered estate, which must be cleared of its indebtedness, that no stain might rest upon the name of Harding. There was a gleam in the dark eyes, and a ring to the voice of the boy as he spoke, that kindled the admiration of the Club, and when he ceased speaking, Miller reached out and shook his hand, saying: "You should have the money, my boy!"

Back in Massachusetts, Brewster had met with a whole train of misfortunes; his property had become involved; his wife had died – his voice lowered and grew husky when mentioning this – he had two little girls, Mable and Mildred. He had kept his children at school and paid their way despite the iron fortune that had hedged him about, and he was working to shield them from all the sorrows possible, without the aid of the Saint who had gone to heaven. The Club was silent for a moment, when the strong man added, solemnly, and as if to himself: "Who knows that she does not help us still?"

In his youth, Brewster acquired the trade of an engineer. At this time, as we learned before, he was running a power drill in the Bullion. He was a great reader and was thorough on many subjects.

Wright had his eyes on a stock range in California, where the land was cheap, the pasturage fine, the water abundant, and where, with the land and a few head of stock for a beginning, a man would in a few years be too rich to count his money. He had been accustomed to stock, when a boy, in Missouri, and was sure that there was more fun in chasing a wild steer with a good mustang, than finding the biggest silver mine in America.

Ashley had gained some new ideas since coming West. He believed he knew a cheap farm back in Pennsylvania, that, with thorough cultivation, would yield bountifully. There were coal and iron mines there also, which he could open in a way to make old fogies in that country open their eyes. He knew, too, of a district there, where a man, if he behaved himself, might be elected to Congress. It was plain, from his talk, that he had some ambitious plans maturing in his mind.

Corrigan had an old mother in New York. He was going to have a few acres of land after awhile in California, where grapes and apricots would grow, and chickens and pigs would thrive and be happy. He was going to fix the place to his own notion, then was going to send for his mother, and when she came, every day thereafter he was going to look into the happiest old lady's eyes between the seas.

So they talked, and did not note how swiftly the night was speeding, until the deep whistle of the Norcross hoisting engine sounded for the eleven o'clock shift, and in an instant was followed by all the whistles up and down the great lode.

Then the good nights were said, and in ten minutes the lights were extinguished and the mantles of night and silence were wrapped around the house.

CHAPTER III

An early breakfast was prepared by the whole Club, as the supper of the previous evening had been. The miners had to be at the mines, where they worked, promptly at 7 o'clock, to take the places of the men who had worked since eleven o'clock the previous night.

While at breakfast the door of the house was softly opened and a Chinaman showed his face. He explained that he was a "belly good cook," and would like to work for ten dollars a week.

Carlin was nearest the door, and in a bantering tone opened a conversation with the Mongolian.

"What is your name, John?"

"Yap Sing."

"Are you a good cook, sure, Yap?"

"Oh, yes, me belly good cook; me cookie bleef-steak, chickie, turkie, goosie; me makie bled, pie, ebbything; me belly good cook."

"Have you any cousins, Yap?"