полная версия

полная версияThe Vote That Made the President

David Dudley Field

The Vote That Made the President

THE VOTE THAT MADE THE PRESIDENT

At ten minutes past four o'clock on the second morning of the present month (March, 1877), the President of the Senate of the United States, in the presence of the two Houses of Congress, made this announcement: "The whole number of the electors appointed to vote for President and Vice-President of the United States is 369, of which a majority is 185. The state of the vote for President of the United States, as delivered by the tellers, and as determined under the act of Congress, approved January 29, 1877, on this subject, is: for Rutherford B. Hayes, of Ohio, 185 votes; for Samuel J. Tilden, of New York, 184 votes;" and then, after mentioning the votes for Vice-President, he proceeded: "Wherefore I do declare, that Rutherford B. Hayes, of Ohio, having received a majority of the whole number of electoral votes, is duly elected President of the United States for four years, commencing on the fourth day of March, 1877."

Mr. Hayes was thus declared elected by a majority of one. If any vote counted for him had been counted on the other side, Mr. Tilden, instead of Mr. Hayes, would have had the 185 votes; if it had been rejected altogether, each would have had 184 votes, and the House of Representatives would immediately have elected Mr. Tilden. One vote, therefore, put Mr. Hayes into the presidential office.

To make up the 185 votes counted for him, 8 came from Louisiana and 4 from Florida. Whether they should have been thus counted is a question that affects the honor, the conscience, and the interests of the American people. There is not a person living in this country who has not a direct concern in a just answer. Not one will ever live in it whose respect for this generation will not depend in some degree upon that answer.

The 12 votes were not all alike. Some had one distinction, some another. But, not to distract attention by the discussion of several transactions instead of one, and because one in the present instance actually determined the result, I will confine my observations to a single vote. For this purpose let us take one of the votes from Louisiana, that, for instance, of Orlando H. Brewster.

Brewster was not appointed an elector, inasmuch as he did not receive a majority of the votes cast by the people of Louisiana, and inasmuch also as he could not have been appointed if he had received them all.

He did not receive a Majority of the VotesIt would be a waste of time and patience to go through the testimony taken by the two Houses of Congress for their own information, before they consented to call in the advice of the Electoral Commission. The evidence of wrongs on both sides, and the irreconcilable contradictions of witnesses, made President Seelye and Mr. Pierce, of Massachusetts, declare it to be impossible for them to reach a satisfactory conclusion upon the facts, and compelled them to break away from their party, and refuse to abide by the advice of the Commission. There are certain things, however, which we know beyond dispute, or about which there is and can be no controversy, and these only will I mention. We know that the number of votes cast in Louisiana for the Tilden electors, taking the first name on the list as representing all, was 83,723, but that the certificate of the Returning Board put them at 70,508, turning Mr. Tilden's majority of more than 6,000 into a majority for Mr. Hayes; and we know that the reduction was made by throwing out more than 13,000 votes of legal voters voting legally for Mr. Tilden, and that more than 10,000 of these were thrown out upon the assumed authority of a statute of Louisiana, which in terms gave the board power to throw out votes, upon examination and deliberation, "whenever, from any poll or voting-place, there shall be received the statement of any supervisor of registration or commissioner of election, in form as required by section 26 of this act, on affidavit of three or more citizens, of any riot, tumult, acts of violence, intimidation, armed disturbance, bribery, or corrupt influences, which prevented, or tended to prevent, a fair, free, and peaceable vote of all qualified electors entitled to vote at such poll or voting-place."

Whether the statute itself has its warrant in the Constitution is a question not necessary now to be considered. For my part, I cannot see the authority for taking out of the ballot-boxes the ballots of lawful voters and throwing them away because other voters did not vote, whatever may have been the cause of their not voting, whether they were frightened, foolish, or perverse. I cannot for the life of me perceive that the State can be held to have elected persons whom it did not in fact elect, because it is conjectured, or even made probable, that if voters who kept away from the polls had in fact attended and voted, they would have made a majority for these persons.

Without going into that question, however, and assuming for the sake of the argument that the statute had all the authority of the most clearly valid statute that was ever passed, it is certain that the only ground upon which a vote could have been thrown out, for intimidation or other corrupt influence, was the statement of a supervisor of registration or commissioner of election, founded upon the affidavits of three citizens. When, however, the vote of Louisiana was before the Electoral Commission, the following offer was made by counsel:

"We offer to prove that the statements and affidavits purporting to have been made and forwarded to said Returning Board in pursuance of the provisions of section 26, of the election law of 1872, alleging riot, tumult, intimidation, and violence, at or near certain polls, and in certain parishes, were falsely fabricated and forged by certain disreputable persons under the direction, and with the knowledge, of said Returning Board, and that said Returning Board, knowing said statements and affidavits to be false and forged, and that none of the said statements or affidavits were made in the manner or form or within the time required by law, did knowingly, willfully, and fraudulently, fail and refuse to canvass or compile more than 10,000 votes lawfully cast, as is shown by the statements of votes of the Commissioners of Election."

This offer the Commission rejected by a vote of 8 to 7.

In the Commission Mr. Abbott moved the following:

"Resolved, That testimony tending to show that the so-called Returning Board of Louisiana had no jurisdiction to canvass the votes for electors of President and Vice-President is admissible."

This was rejected by the same vote.

In explaining the reason of their decision in the case, the Commission used the following language:

"And the Commission has, by a majority of votes, decided, and does hereby decide, that it is not competent, under the Constitution and the law as it existed at the date of the passage of said act, to go into evidence aliunde, the papers opened by the President of the Senate, in the presence of the two Houses, to prove that other persons than those regularly certified to by the Governor of the State of Louisiana, on and according to the determination and declaration of their appointment by the returning officers for elections in the said State prior to the time required for the performance of their duties, had been appointed electors, or by counter-proof to show that they had not; or that the determination of the said returning officers was not in accordance with the truth and the fact, the Commission, by a majority of votes, being of opinion that it is not within the jurisdiction of the two Houses of Congress, assembled to count the votes for President and Vice-President, to enter upon a trial of such questions."

Whether, therefore, the decisions of the Commission or the reasons given for them be sound or unsound, it may be assumed, that Brewster did not receive a majority of the votes cast by the people of Louisiana, and that the action of the Returning Board in cutting down the majority of his competitor, so as to reduce it below his, was taken without jurisdiction, and upon the pretense of statements and affidavits which they themselves had caused to be forged.

Brewster could not have been appointed Elector if he had received the Votes of all the People of LouisianaHe had been made Surveyor-General of the United States, for the District of Louisiana, on the 2d of February, 1874; was recommissioned by President Grant on the 11th of February, 1875, and is at present exercising the office. Whether he has ever been out of the office depends upon the facts now to be mentioned. Eight or nine days after the election of November 7, 1876, at which he was a candidate on the Republican electoral ticket, there was received at the Department of the Interior, from the hands of the President, this letter:

Monroe, November 4, 1876.Dear Sir: I hereby tender my resignation of the office of Surveyor-General of the State of Louisiana, with the request that it be accepted immediately. With many thanks for your kindness,

I remain, yours respectfully,O. H. Brewster.U. S. Grant, President United States.

When the letter was written does not appear. It is certain that Brewster was acting as Surveyor-General on the 10th of November.

On the 16th of November a letter was addressed to the Commissioner of the General Land-Office, as follows:

Department of the Interior,Washington, November 16, 1876. }Sir: I have received the resignation of Mr. Orlando H. Brewster, Surveyor-General of Louisiana, which he has requested may take effect immediately. Please inform Mr. Brewster that his resignation has been accepted by the President, to take effect November 4th instant, that being the date of his letter of resignation to this Department.

Very respectfully,Z. Chandler, Secretary.At what time, if ever, the Commissioner informed Brewster of the acceptance of his resignation we do not know, but it could not have been earlier than the 20th of November.

On the morning of the 6th of December, the four men who assumed to act as the Returning Board of Louisiana filed in the office of the Secretary of that State a certificate that Brewster, with seven other persons, had been appointed presidential electors. There was then on the statute-book of Louisiana this enactment:

"If any one or more of the electors chosen by the people shall fail from any cause whatever to attend at the appointed place at the hour of 4 p. m. of the day prescribed for their meeting, it shall be the duty of the other electors immediately to proceed by ballot to fill such vacancy or vacancies."

What Brewster did is thus told by Kellogg, one of the Hayes electors, on his examination at Washington in January:

"Q. Did Levissee and Brewster vote at the meeting of electors?

A. I believe they did.

Q. Was not an appointment made for somebody to fill Brewster's place?

A. I believe that that is the case.

Q. Who was appointed to fill Brewster's place?

A. Brewster himself.

Q. The same man?

A. The same man.

Q. Were you also instructed by these committees (National and Congressional Republican Committees) how to dispose of Brewster and Levissee?

A. My recollection is that some one of the electors had received a letter suggesting that in case of a vacancy or in case of the absence of Levissee and Brewster, they should be chosen in their own places. That is my recollection.

Q. And yet they absented themselves from the electoral college, and you filled their vacancies with themselves?

A. They were absent from the college when the college met, and we filled their vacancies by themselves."

Being thus installed, they voted for Mr. Hayes within an hour after they were chosen to fill their own vacancies; and three days afterward Brewster addressed the following letter to the President:

New Orleans, Louisiana, December 9, 1876.Sir: I respectfully apply to be appointed Surveyor-General for the District of Louisiana. Commendations from prominent gentlemen will be submitted to your Excellency to justify the appointment.

I have the honor to remainYour very obedient servant,Orlando H. Brewster.U. S. Grant, President United States, Washington, D. C.

The reappointment was made on the 5th of January, 1877. The Chief of the Appointment Division in the Interior Department was asked and testified about it as follows:

"Q. Who recommended his appointment in January?

A. I think the probability is (although there is no evidence of it) that there was no recommendation, further than his own application to the President.

Q. You do not know of any recommendation?

A. I do not know of any.

Q. There is none on file?

A. There is none on file to the best of my knowledge. There is none on file in the Interior Department."

Who does not perceive the shallow trick by which Brewster pretended to have divested himself of his Federal office that he might vote; only to be reinvested as soon as he had voted?

The letter of resignation, with its false date, and its pretended acceptance, to take effect as of a time past, were evident shams to make it appear that he was not holder of a Federal office when he was elected; his affecting to be absent on the 6th of December, and coming in immediately to fill the vacancy occasioned by his own absence, in order to make it appear that his appointment was made on that 6th of December, instead of the 7th of November, and his barefaced application on the third day thereafter to be reappointed to the Federal office, from which he could not possibly have perfected his resignation before the 20th of November – all these were but so many contrivances to evade the highest enactment known to our civil polity. In the eye of reason and of law, he acted during the whole period under that influence of office which it was the design of the Constitution to prevent, and he must have entered more thoroughly into the work of his Federal master than if he had not gone through the form of resigning, inasmuch as that placed him, more than before, in his master's power.

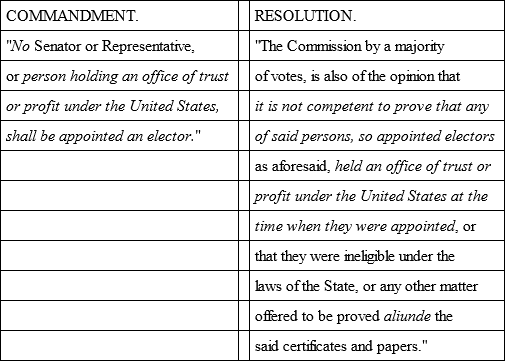

Let us now place side by side the commandment of the Constitution and the resolution of the Electoral Commission:

It would be unjust to cast upon the Electoral Commission the blame of all the wrong that has been practised in this presidential count. The Commission was but a council of advice, which Congress might have taken or not, as it pleased, the only condition being that, in order to reject it, both Houses must have agreed. The responsibility of the final decision lay, after all, upon Congress, or rather, upon the Senate, which voted throughout to follow the Commission.

The facts thus briefly recited present certain questions – moral, political, and legal – which cannot be considered too soon for our good repute and our self-respect.

The Moral QuestionWhatever differences of opinion there may be about the political and legal questions involved, there can be none about the moral. The presidential office is the gift of the people of the several States, of their own free-will, expressed according to the laws. A falsification of that will is an offense against the State where it is committed, and against all the States. If the falsification is beyond the reach of the law, it is not beyond the reach of the conscience. A robbery is none the less a robbery because it is beyond the range of vision or the arm of justice. If the possessor of an estate has entered through the forgery of a record or the spoliation of a will, which although believed by every neighbor is beyond judicial proof, all the world pronounces his possession fraudulent, even though he scatters his wealth in charities and gathers many companions around his luxurious table. The example is corrupting, but it is against the eternal law of justice that the act should be respected or the actors continue forever to prosper.

It is no answer to these observations to say that frauds have been practised on the other side. Unhappily there is too much reason to believe that neither party is free from practices which are at once a scourge and a dishonor. Neither has the disgraceful monopoly of such practices, whichever may have the bad preëminence. But this is certain: one wrong neither justifies nor palliates another.

There is no set-off known to the moral law. Because A has defrauded B, that is no reason why B should defraud A. If it were so, society would go on forever in a compound ratio of crime. The first breach of the law would furnish excuse for the second, and their progeny would follow in sad progression to the end of time. This is not, however, the moral condition of the world. The lex talionis has been abolished by the law of civilization and the higher law of the gospel.

In this case of Louisiana there can be neither excuse nor palliation for the misconduct of the Returning Board.

On the 10th of November, President Grant telegraphed to the General of the Army instructions about troops in Louisiana and Florida, and added that "no man worthy of the office of President should be willing to hold it if counted in or placed there by fraud. Either party can afford to be disappointed in the result. The country cannot afford to have the result tainted by the suspicion of illegal or false returns." And again: "The presence of citizens from other States, I understand, is requested in Louisiana, to see that the Board of Canvassers makes a fair count of the vote actually cast. It is to be hoped that representative and fair men of both parties will go."

Did the President of that day misrepresent his party, or his successor, or has the party changed and the successor also? Had the virtuous impulses of November faded away in February? Was there a change of heart or a change of opportunity? Neither Congress nor the Electoral Commission could give an honest title, without investigating the honesty of the transactions on which the title was founded; and yet a President has been installed, in the face of rejected offers to prove frauds, the grossest, the most shameless, and the most corrupting, in all our history.

Then what was the object of the committees of each House of Congress, sent into the disputed States? Was it to blind the people? Was it to conceal a meditated fraud? On the very first day of the session, December 4th, Mr. Edmunds, in the Senate, moved certain resolutions, of which this was one:

"Resolved further, That the said committee" (the Committee on Privileges and Elections) "be, and is hereby, instructed to inquire into the eligibility to office under the Constitution of the United States of any persons alleged to have been ineligible on the 7th day of November last, or to be ineligible as electors of President and Vice-President of the United States, to whom certificates of election have been, or shall be, issued by the Executive authority of any State, as such electors, and whether the appointment of electors, or those claiming to be such, in any of the States, has been made either by force, fraud, or other means otherwise than in conformity with the Constitution and laws of the United States, and the laws of the respective States; and whether any such appointment or action of any such elector has been in any wise unconstitutionally or unlawfully interfered with; and to inquire and report whether Congress has any constitutional power, and, if so, what and the extent thereof, in respect of the appointment of or action of electors of President and Vice-President of the United States, or over returns or certificates of votes of such electors," etc.

Was all this parade of committees sent hither and thither, summoning witnesses from far and near, committing the recusant to prison, and looking into State archives; was all this a mock show, a piece of pantomime, for the amusement of the lookers-on, while conspirators were plotting how to conceal what they pretended to be wishing to discover? Taken all in all, the sounding profession, the bustling search, and the studied concealment, make a drama, half comedy and half tragedy, the like of which this generation has not seen till now, but the like of which it and its successors may see many times, if the audience does not hiss the play, and remit the actors to the streets.

It has been objected, as a reason for not receiving offered evidence, that there was not time to take it before the 4th of March. How was that known? Perhaps it could have been taken in an hour. Why was not the question asked, how much time the evidence would take, before it was excluded? If the certificate was false, and the falsehood was susceptible of proof, every effort possible should have been made to receive it, and receive it all. It is not commonly accepted as good reason for not searching after the truth, that the search may be difficult. Nor is it an unusual occurrence to require an argument or decision to be made within a period limited. Ten minutes' speeches in Congress, two hours' argument in the Supreme Court, a jury shut in a room until they agree upon a verdict, a court required by statute to render its decision by a day fixed, are not so strange as to be remarkable, or found in practice so embarrassing as to cause the practice to be abandoned.

Nor is it any answer to say that, if the offer of evidence had been accepted, the proof would have fallen short of the offer. That does not lie in the mouth of any one to say, who excluded the evidence, or justified its exclusion. The characters of the counsel who made the offer, and of the commissioner who moved its acceptance, are a guarantee not only of their good faith, but of a reason for their belief. No man has any right to deny that the proof offered would have been made good, who refused the opportunity. They who closed their ears should in decency keep their mouths shut. But it was not the counsel and the commissioner alone who believed that the proof offered would be made good. Every one who witnessed the examinations in Washington, every one who read the testimony taken by the Congressional Committees in Louisiana, must have been satisfied that the conduct of the Returning Board was throughout unlawful, wicked, and shocking, to the last degree.

The title of the acting President, however valid in law, if valid at all, is tainted with fraud in fact. There was fraud in certifying that Brewster had received a majority of the votes of Louisiana, and fraud in attempting to evade that part of the Constitution which pronounced his disqualification. When the Electoral Commission advised Congress, and Congress accepted, by not rejecting, the advice, that fraud could not be proved, that advice being but the equivalent of saying that fraud was of no consequence; when it advised that the incompetency of the Returning Board, for want of jurisdiction, could not be proved, such proof being but the equivalent of proof that the pretended board was not a board at all; when it advised that the forgery, by direction of the board, of the statements and affidavits on which it pretended to act as true could not be proved, that proof being but the equivalent of proof that the pretended statements and affidavits were not statements and affidavits at all; when it advised that the barrier raised by the Constitution against the appointment of a Federal officer to choose a Federal President, was not a barrier at all – the moral sense of the whole American people was shocked. No form of words can cover up the falsehood; no sophistry can hide it; no lapse of time wash it out. It will follow its contrivers wherever they go, confront them whenever they turn, and as often as one of them asks the suffrages of his countrymen, he may expect to hear them reply, "Why do you reason with us, why seek to persuade us into giving you our votes, you that have taught us such a contempt for votes, that one fraudulent certificate is better than ten thousand of them?"