полная версия

полная версияBacteria in Daily Life

The Danes are enlightened and shrewd enough to realise that in order to retain their existing markets and acquire fresh ones, it is necessary to take advantage of every improvement in methods of manufacture which scientific research has placed at their disposal, and their reward is justly reaped in the prosperity of their dairy industry and the high reputation enjoyed by their produce. If we contrast the adaptability and elasticity of the continental mind in regard to new discoveries with the crude conservatism of the British manufacturer, then, indeed, is the success of our rivals and corresponding decline of our own prosperity most perfectly intelligible.

Again, we are informed that the recent visit to London of a deputation representing Russian agricultural interests is already bearing fruit, and contracts have been signed for the regular importation of large quantities of Russian dairy produce. The English market is already well supplied with Russian eggs, but an opening has now been found here for the disposal of Russian butter and cheese.

Finland, again, the total population of which is less than half that of London, exports to this country no less than 12 million marks' worth of butter annually.

As a writer recently put it: "Foreigners and colonists have captured our butter markets; if the consumption of milk sterilised in bottles becomes the fashion, they will likewise capture our milk markets." And this is no fanciful suggestion, for whilst the production of Pasteurised milk does not involve any considerable outlay in apparatus, its transport may be effected with the greatest ease. Indeed, frozen milk has been introduced into England from Norway and Sweden. It is first Pasteurised, then frozen in large wooden boxes, and shipped in the congealed condition, in which state it remains unchanged for a long period of time.

But it is undoubtedly with the public that the responsibility really rests, for as long as it does not care to create the demand for Pasteurised dairy products all the efforts of enlightened agricultural authorities in this country must inevitably end in failure.

On the Continent and in America dairy-bacteriology, as already pointed out, has made enormous strides, and has practically revolutionised the conduct of dairy work; and if we could but rouse ourselves from our lethargy we likewise should be able not only to boast of progress, but also to better hold our own ground in this important branch of agriculture; and one result would be that dairy troubles, which for so long have been accepted as more or less necessary evils, would yield here, as they have done elsewhere, to a more rigid attention to details, the significance of which scientific research has so successfully shown.

Some of the most easily preventable, but at the same time most aggressively assertive, dairy troubles are undoubtedly directly dependent upon the conduct of milking operations.

In the first place, the cow itself is only too frequently in an uncleanly condition, and as its coat offers exceptional facilities for the harbouring of dust and dirt, the danger of foreign particles falling into the milk is always present unless precautions are taken to negative, or at least minimise, all such chances of contamination.

Professor H. L. Russell, of the Wisconsin Agricultural Experiment Station, cites in his little volume on Dairy Bacteriology an instructive experiment which brings home very forcibly the importance of such precautions. A cow pastured in a meadow was selected for the experiment, and the milking was done out of doors, so as to eliminate as far as possible any intrusion of disturbing foreign factors into the experiment, such as the access of microbes from the air in the milking-shed. The cow was first partially milked without any precautions whatever being taken, and during the process a small glass dish containing a layer of sterile nutrient gelatine was exposed for one minute beneath the animal's body, in close proximity to the milk-pail. The milking was then interrupted, and before being resumed the udder, flank, and legs of the animal were thoroughly cleansed with water; a second gelatine surface was then exposed in the same place and for the same length of time. The results of these two experiments are very instructive. When the cow was milked without any special precautions being taken, 3,250 bacteria were deposited per minute on an area equal to the surface of a ten-inch milk-pail; after, however, the animal had been cleansed, only 115 bacteria were deposited per minute on the same area.

Thus a large number of organisms can, by very simple precautions and very little extra trouble, be effectually prevented from obtaining access to milk. Even in the event of the milk being subsequently Pasteurised, clean milking is of very great importance; but still more imperative is it when it is destined for consumption in its raw, uncooked condition. If we consider how cows become covered with dirt and slime, that obstinately adhere to them when they wade through stagnant ponds and mud, and realise the chance thus afforded for malevolent microbes to exchange their unsavoury surroundings for so satisfactory and nourishing a material as milk, then indeed precautions of cleanliness, however troublesome, will not appear superfluous.

That a very real relationship does exist between the bacterial and dirt contents of milk has been clearly shown by actual investigation. A German scientist has made a special study of the subject, and has determined in a large number of milk samples the amount of foreign impurities present per litre, and the accompanying bacterial population per cubic centimetre.

The following results may be taken as typical of those obtained: in milk containing 36·8 milligrammes of dirt per quart as many as 12,897,600 bacteria were present per cubic centimetre; in cleaner samples, with 20·7 milligrammes of dirt per quart, the number of bacteria fell to 7,079,820; whilst in a still more satisfactory sample, containing 5·2 milligrammes of dirt per quart, there were 3,338,775 bacteria per cubic centimetre.

Such results indicate how important a factor is scrupulous cleanliness in milking operations in determining the initial purity of milk, for there is no doubt that bacterial impurities in milk are in the first instance, to a very great extent, controlled by the solid impurities present.

I do not know of any determinations which have been made of the actual amount of such solid impurities present in our public milk-supplies, but such estimations have been made in many of those belonging to large cities in Germany. Thus, Professor Renk found in a litre of milk supplied to Halle about 75 milligrammes, whilst in another sample as much as 0·362 grammes per litre were detected. In Berlin 10 milligrammes, and in Munich 9 milligrammes per litre, were found. Dr. Backhaus has estimated that the city of Berlin alone consumes daily with its milk no less than 300 cwt. of cow-dung. If we associate these amounts of solid impurities with their consequent bacterial impurities, then we shall obtain some idea of what the microbial population of these milk-supplies may amount to.

These impurities are almost wholly preventable, but, unfortunately, but little importance is apparently attached to their presence in milk as a rule by dairymen.

In a letter published in the Sussex Daily News a correspondent and well-known authority on dairy matters sounds a timely note of warning to our dairy managers: —

"I happen to know," he writes, "for a fact that Americans who visited one of our Dairy Shows at Islington were so disgusted at the method – or rather lack of cleanly method – exhibited there as our ordinary way of milking cows, that these visitors stated that nothing would induce them to drink milk while in England. I mention this circumstance so as to bring home to the minds of English dairy-farmers who may read this letter how very backward we are in this country as compared with more studious and careful foreign competitors. It is insisted upon by our foreign teachers that our cow-stalls are too short and not roomy enough, and our cow-houses badly constructed; that we do not (1) groom our cows or (2) clean the teats, nor (3) sponge their udders, bellies, and sides before milking with clean, tepid water; (4) that the milkers do not tie up the cow's tail nor clean their own hands and persons, nor (5) cover their clothes with a clean, well-aired blouse during milking; that (6) they generally milk in a foul atmosphere (bacterially), tainted with the odour of dung, brewer's grains, or farmyard refuse. I am sorry to state that there is too much solid fact about the contentions which, based upon bacteriology, are given as causes of injury to quality… Cleanliness is now a matter requiring the primary attention of English dairy-farmers. The study of bacteria proves that such inattention is greatly the cause of foreign butters beating ours."

It follows as a natural sequence that all the cans and vessels used for dairy purposes should be absolutely beyond suspicion of contamination. Professor Russell has shown by actual experiment that, even where the vessels are in good condition and fairly well cleaned, the milk has a very different bacterial population when collected in them and in vessels sterilised by steam.

Two covered cans were taken, one of which had been cleaned in the ordinary way, and the other sterilised by steam for half an hour. Previous to milking the animal was carefully cleaned, and special precautions were taken to avoid raising dust, whilst the first milk, always rife with bacteria, was rejected. Directly after milking bacterial gelatine-plates were respectively prepared from the milk in these two pails, with the following results: In one cubic centimetre of milk taken from the sterilised pail there were 165 bacteria; in that taken from the ordinary pail as many as 4,265 were found.

Another experiment illustrates perhaps even more strikingly the effect of cleanly operations in milking upon the initial bacterial contents of milk. The preliminary precautionary measures were carried out by an ordinary workman, and are in no sense so refined as to be beyond the reach of ordinary daily practice. "The milk was received in steamed pails, the udder of the animal, before milking, was thoroughly carded, and then moistened with water, so as to prevent dislodgment of dirt. Care was taken that the barn air was free from dust, and in milking the first few streams of milk were rejected. The milk from a cow treated in this way contained 330 bacteria per cubic centimetre, while that of the mixed herd, taken under the usual conditions, contained 15,500 in the same volume. The experiment was repeated under winter conditions, at which time the mixed milk showed 7,600 bacteria per cubic centimetre, while the carefully secured milk only had 210 in the same volume. In each of these instances the milk secured with greater care remained sweet over twenty-four hours longer than the ordinary milk."

An organism which has exceptional opportunities for finding its way into cows' milk is the Bacillus coli communis, normally present in the fæces of all animals. This microbe is a very undesirable adjunct to milk, and may greatly interfere with the souring process, by multiplying extensively, and so producing a change in the milk which renders it impossible for the particular souring bacteria to carry on their work, resulting in their collapse and ultimate extinction. But this is not the only injurious effect which these Coli bacilli can produce in milk, for there is a growing conviction that their presence is responsible for many intestinal disturbances with which young children are specially troubled. Quite recently determinations of the bacterial contents of cow-dung have been made, and it has been ascertained that a single gramme,6 freshly collected, of this material may contain as many as 375,000,000 bacteria, of which the majority were found to be the above undesirable organism, the B. coli communis.

Milk may also contain bacteria characterised by their remarkable resistance to heat, which is due to their possessing what is known as the hardy spore in addition to the ordinary rod form. The numbers in which they are present in milk varies with different samples; but they may be taken as a sort of index as to the care observed in milking, for they are always present in great quantity in uncleanly-collected milk. Careful studies have been made of this class of milk bacteria by Professor Flügge and others, and it has been found that when added to milk upon which puppies were subsequently fed the latter succumbed under symptoms of violent diarrhœa.

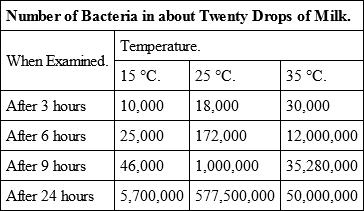

The danger of even a few bacteria gaining access to milk is serious, on account of the fabulous rapidity with which they multiply when they find themselves in such congenial surroundings. Professor Freudenreich has made very exhaustive investigations to show how milk microbes may multiply in the time which elapses between milking and the receipt of the milk by the consumer. The following example will convey some notion of what bacterial propagation under these circumstances is capable of.

The sample of milk in question was found to possess on reaching the laboratory, two and a half hours after milking, a little over 9,000 bacteria in a cubic centimetre. The sample was divided into three portions, which were kept at different temperatures, and after definite intervals of time they were examined. The following table shows at a glance the results obtained: —

Thus, after being kept in the laboratory for three hours the original 9,000 bacteria had in one case doubled, and in another more than trebled themselves. It will be seen that the temperature most favourable to the multiplication of these bacteria was 25 degrees Centigrade.

If a sample of milk containing originally such a comparatively small number of bacteria – for a figure under 10,000 per cubic centimetre sinks into utter insignificance when we read of samples containing 2,500,000 – if such relatively bacterially pure samples may support such prodigious numbers of these Lilliputians, what the microbial population of less satisfactory samples may amount to well-nigh baffles our powers of calculation. Professor Russell writes: "If we compare the bacterial flora of milk with that of sewage, a fluid that is popularly, and rightly, supposed to be teeming with germ life, it will almost always be observed that milk when it is consumed is richer in bacteria by far than the sewage of our large cities. Sedgwick, in his Report to the Massachusetts Board of Health for 1890, found that the sewage of the city of Lawrence contained at the lowest 100,000 germs, whilst the maximum number was less than 4,000,000 per cubic centimetre.7 This range in numbers is much less than is usually found in the milk-supply of our large cities."

Numerous researches have been carried out during the last half-dozen years to try and localise the origin of some of the principal dairy troubles, with a view to their possible extinction, or at least control. In the course of these investigations quite a number of the bacteria found in milk have been successfully hunted down, and their offences brought home to them.

Thus, from so-called "bitter" milk a bacillus has been isolated by Professor Weigmann, and found responsible for this particular change. Another microbe was discovered in bitter cream whose office apparently consisted in rendering milk strongly acid and extremely bitter. Again, that objectionable condition of milk known as slimy, ropy, or stringy, is brought about by certain bacteria which render it viscous; whilst another crop of microbes are occupied in conferring upon it the power of sticking to everything that touches it, making it capable of being drawn out into threads from several inches to several feet in length.

Although we object in this country to slimy milk, in Holland it is in special request for the production of a certain cheese known under the name of Edam. In Norway this kind of milk forms a popular drink called Taettemjolk, and to produce it artificially they put the leaves of the common butter-wort (Pinguicula vulgaris) into milk. Professor Weigmann has discovered a micro-organism which frequents the leaves of this plant endowed with particular powers of producing slimy milk, and doubtless the credit of furnishing Taettemjolk is really due to this microbe, and not to the innocent butter-wort. "Soapy" milk, again, has been traced to a specific germ discovered in large numbers in straw used for bedding, whilst it was also detected in the hay that served for fodder. During milking these sources had supplied the infection, and the peculiar fermentation was distinctly shown to be microbial in origin. So-called red and blue milk, and those various hues ranging from bright lemon to orange and amber, are also now known to be directly attributable to bacterial activity.

But of even greater significance than all these bacterial dairy troubles is the risk of spreading disease which is furnished by milk contaminated with pathogenic micro-organisms.

"There can be no shadow of doubt," said the Lancet now many years ago, "that the contagia of typhoid and scarlet fever are disseminated by milk, and that boiled milk enjoys a much greater immunity from the chance of conveying disease."

This was written at a time when the study of bacteria was yet in its infancy, and before any direct experimental evidence had been obtained on the behaviour of microbes in milk or concerning the part played by them in the dissemination of disease. The writer evidently did not venture to cast further aspersions on the character of milk, or he might have included diphtheria amongst the diseases which can be spread by its means; but there is another omission which still more conclusively indicates the remote age in the history of bacterial science at which this correspondent to the Lancet wrote, and that is the absence of all reference to the tubercle bacillus in relation to milk. At the present day hardly a bacteriological journal is published which does not contain some reference to the question of tuberculosis and milk, and the transmissibility of this disease when present in cattle to man.

As regards the dissemination of various zymotic diseases by milk, the evidence which has been collected points very conclusively to the responsible part which may be played by milk in this connection. Many instances have been cited, also, of the culpability of milk in distributing typhoid germs. A striking case which occurs to me, and which may be mentioned in passing, is one which occurred in a city in America a few years ago, in which an outbreak of this disease was traced to a dairy in which the vessels had been washed out with typhoidal-polluted water. No less than 386 cases of typhoid declared themselves in six weeks, and of this number over 97 per cent. occurred amongst families obtaining their milk from the same dairy. A careful inspection revealed the fact that the milk-cans had been rinsed out with water from a shallow well contaminated with typhoid dejecta.

Diphtheria is also justly associated with infected milk, and if we take into consideration the now established fact that diphtheria bacilli thrive and multiply with particular facility in milk, even more so than in ordinary broth cultures; that they have been found in air in a vital and virulent condition, and may be scattered far and wide attached to dust particles; and if we remember the numerous opportunities offered for the infection of milk by persons handling it, who either themselves are suffering from this disease or are in diphtheria surroundings – then indeed we can readily understand how milk becomes a diphtheria-carrier of the first order.

Tuberculosis in cattle, and how this disease may affect the character of dairy produce, is, as already pointed out, a subject which is attracting the attention of a large number of investigators.

The general public is perhaps hardly aware of how widespread this disease is amongst cattle, and it is only of late years that very careful inquiries have elicited the fact that it is not only very extensively distributed, but may be present in animals to all outward appearance in perfect health.

In Germany it was asserted a few years ago that every fifth cow was tuberculous, and even this was regarded as a moderate estimate. The distinguished Danish pathologist, Professor Bang, is responsible for the announcement that during the years 1891-3 17·7 per cent. of the animals slaughtered in Copenhagen were infected with tuberculosis. In Paris we have been told that, of every thirteen samples of milk sold, one was infected with tubercle bacilli, whilst in Washington one in every nineteen samples of milk was stated to be similarly tainted.

The existence of tubercular disease in cows, and its transmission to other animals fed with their milk, has been brought out in a striking manner in investigations published by the Massachusetts Society for the Promotion of Agriculture. In one case as many as over 33 per cent. of the calves fed with milk from tuberculous cows succumbed to the same disease. According to Hirschberger, 10 per cent. of the cows living in the neighbourhood of towns where the conditions of their environment are not generally the most satisfactory or conducive to health suffer from tuberculosis, and 50 per cent. of these animals yield milk containing tubercle bacilli.

The demand which is being made by municipal authorities to be invested with the power of inspecting the country farms from whence their cities are supplied with milk and other agricultural produce could not have received stronger support than was recently supplied by a case tried in Edinburgh, and as this is only a sample of what is doubtless a daily, although undetected occurrence in many municipalities, it will not be out of place to quote the following from the published report of the proceedings: —

"A cow was brought into the city for sale as food, and the evidence showed it to be in the last stages of tubercular disease. 'Its head was hanging down; it breathed with difficulty, and it had frequent fits of coughing; while its udder was swollen with the disease.' All the organs were diseased, and the milk teemed with bacilli. Yet, it seemed, the milk from this animal had been regularly sent into Edinburgh for sale. In face of facts like these, it is difficult to see on what grounds the claim of towns to inspect country dairies doing a town business can be resisted. At least the towns should have the power to refuse admission to milk from sources not open to inspection. It is not enough for the county authorities to say that they inspect the dairies in their own areas. In this case the condition of the animal was only found out when it was brought into the town to be sold for food."

Further comment is unnecessary!

Some German investigators have discovered the interesting fact that the centrifugal method of separating milk not only has a remarkable effect upon its bacterial contents, but also upon tubercle bacilli when present. On examining the so-called "separator slime," it is found to contain not only large quantities of solid matters, but also masses of bacteria which have been thrown out during the operation. This method of treating milk has, curiously, a particular effect upon tubercle bacilli present, for Professor Scheurlen has found that they are nearly all left in the slime. Naturally his observation was not slow in being tested by other investigators; but Professor Bang has quite independently confirmed Scheurlen's discovery, and, still more recently, Moore purposely infected milk with these bacilli, and found that they were deposited in the slime to a most remarkable extent. Coupled, however, with this peculiar behaviour of tubercle bacilli in separated milk is the fact called attention to by Ostertag, that tuberculosis is much more prevalent among swine in Denmark and North Germany, where the centrifugal process in creaming is extensively used, and where, until recently, this slime was given to the animals in its raw, uncooked condition.

Before leaving this subject of separated milk, reference may be made to a danger, which has recently been publicly called attention to, surrounding the use which is made of skim milk. By an arrangement with the farmers who supply the milk, those clients who principally use it for producing butter return the skim milk to them after it has been through the separator, when it is employed for stock-feeding purposes. The milk in large dairies derived from different farmers is mixed, and hence the skim milk which is returned is also mixed. Thus, in the event of the milk from one farm being infected, not only is the whole milk-supply of a particular dairy infected, but, in returning the mixed skim milk likewise infected in its proper proportion to the different farmers, the virus is distributed over several farms. So real is this danger, and such unfortunate results have followed this practice of returning mixed infected skim milk, that since 1894 the Prussian Government has issued special orders for its disinfection by means of heat, in the hope of coping with this difficulty.