полная версия

полная версияSalvation Syrup; Or, Light On Darkest England

Let us now turn to the scheme itself. Let us see what evils are to be remedied, and the nature of the remedy proposed.

In the opening chapters, written almost exclusively by Mr. Stead, there is a vivid, but, of course, exaggerated, picture of the diseases of society. The writer has walked through the “shambles of our civilisation,” until “it seemed as if God were no longer in this world, but that in his stead reigned a fiend, merciless as Hell, ruthless as the grave.” Of course the grave is neither ruthless nor tender; and, of course, it is not Hell, but the God of Hell, that is merciless. But, apart from these criticisms, it is evident that Mr. Booth-Stead or Mr. Stead-Booth, is aware of much preventible evil; nor are we disposed to quarrel with him for calling it “a satire upon our Christianity,” although we might suggest the impossibility of satirising a creed which has to make such shameful confessions after so many centuries of wealth, power, and privilege, and such a supreme opportunity of cleansing the world if it had the capacity for the task. This Christianity has failed – disastrously and ignominiously; yet has it played the dog in the manger, and refused to allow Science and Philosophy a trial; and even now, when condemned and self-condemned, it only whines for another chance, like an old offender for the hundredth time in the prisoners’ dock.

Eighteen centuries after the advent of “the Redeemer,” and in the most pious country in the world, it is Booth’s calculation that one-tenth of the population, or about three millions of men, women, and children are sunk in destitution, vice, and crime. In London alone, the city of churches, where everything but religion is tabooed on Sunday, there are 100,000 prostitutes, 85,000 thieves, and drunkards galore, to say nothing of the paupers, the idle, and the temporarily unemployed. And the disease is getting worse, according to Booth, who declares that something must be done immediately. Well, we will neither dispute his statistics nor his forecast, but just take his plan of campaign and see whether it has the remotest chance of success.

What is General Booth’s scheme for dealing with the “submerged tenth,” or three millions of the poor, the unemployed, and the vicious? And in what spirit will he set to work if he gets the hundred thousand pounds down, with the prospect of the rest of a million pounds afterwards?

Booth is a bold man and his promises are magnificent.

“If the scheme,” he says, “which I set forth in these pages is not applicable to the Thief, the Harlot, the Drunkard, and the Sluggard, it may as well be dismissed without ceremony.”

We suspect that the Sluggard will be the toughest subject of all. Booth has to solve the insoluble problem of how to put nervous energy into a body in which it is constitutionally lacking. Common sense says the thing cannot be done. You may galvanise the Sluggard for a while, but the effect will not last. Energy is not acquired, it is congenital. If Booth would take the trouble to read Mr. Havelock Ellis’s book on Criminals, not to mention more recondite ^ works, he would see that the Sluggard and the Thief are first cousins. Both have a defective vitality, only the Thief, and the Criminal generally, is capable, like all predatory creatures, of spasmodic activity. The type is well known and should be dealt with scientifically. Inveterate criminals should be segregated. There is no necessity to treat them with cruelty. They should be surrounded with comfort, but they should be rigorously prevented from procreating their like. Science shows us that the only permanently successful way of dealing with these classes is to cut off the supply.

Certainly there are many persons in gaol who are not congenital criminals, and these should be dealt with in a spirit of wisdom and humanity. Were they treated like men, subjected to proper discipline, and rewarded for good behavior and industry, instead of being punished so liberally for bad behavior and idleness, most of them would be reclaimed. In ordinary prisons – so wretched, so inhuman, and so imbecile is the system – eighty per cent, of first offenders come back again; while in the one great American prison which is conducted on a better method the percentage is exactly reversed, only twenty per cent, returning to gaol, and eighty per cent, joining the ranks of decent society.

General Booth is not a scientist. He knows nothing of the lessons of Evolution. He is not aware that thousands of men and women are born in every generation who are behind the age. They are types of a vanished order of mankind, relics of antecedent stages of culture. Natural Selection is always eliminating them, and General Booth proposes to coddle them, to surround them with artificial circumstances, and give them a better chance. He does not see that most of them, however propped up by the more energetic and independent, will always bear the stamp of unfitness; nor does he see that he will enable them to beget and rear a more numerous offspring of the same character.

The law of heredity is a stern fact, and it will not budge a hair’s-breadth for General Booth and all the sentimental religionists in the world.

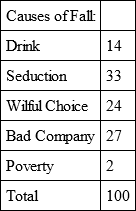

Take the Harlots, for instance. We are far from denying that many girls, after being seduced by men, are pushed into a life of vice. Christian society has no mercy on female frailty; it drives a girl who has listened to the voice of a tempter, or the first suggestions of her sexual passions, into a career of infamy; and then, when it has helped to poison her life, it hypocritically sheds tears over her and sets up associations for her rescue. This is true enough – damnably true – but it is not the whole truth. Just as there are congenital criminals, there are congenital harlots. They are cases of survival or reversion. Discipline of every kind is hateful to them. They prefer to do what they like, how they like, and when they like. Animality and vanity are strong in them, but they have little steady energy and no self-control. In a polygamous state of society they would find a place in a harem; but in a monogamous and industrial state of society they are hopelessly out of harmony with the general environment. Here is an instructive little table from General Booth’s book. He takes a hundred cases “as they come” from his Rescue Register.

Twenty-three of these girls had been in prison. Only two were pushed into vice by poverty. Seduction, wilful choice, and bad company, come to much the same thing in the end. In any case, one-fourth of the whole hundred deliberately took to prostitution. Now:

if General Booth fancies that the money he spends on these is a good investment, while a greater number of good girls are trying to lead an honest life in difficult circumstances, with little or no assistance from “charity,” we venture to say he is grievously mistaken; and we think he is basking in a Fool’s Paradise, unless he is trading on pious credulity, when he looks forward (p. 133) to the girls of Piccadilly exchanging their quarters for “the strawberry beds of Essex or Kent.”

Facts are facts. It is useless to blink them. The present writer did not make the world, or its inhabitants, and he disowns all responsibility for its miserable defects. But when you attempt to reform the world there is only one thing that will help you. Humanity is presupposed. Without it you would never make a beginning. But after that the one requisite is Science. Now all the science displayed in General Booth’s book might be written large on thick paper, and tied to the wrings of a single pigeon without impeding its flight.

General Booth himself, in one of his lucid intervals, recognises the hard facts we have just insisted on. “No change in circumstances,” he says (p. 85), “no revolution in social conditions, can possibly transform the nature of man.” “Among the denizens of Darkest England there are many who have found their way thither by defects of character which would, under the most favorable circumstances, relegate them to the same position.” Again he says (p. 204):

“There are men so incorrigibly lazy that no inducement you could offer will tempt them to work; so eaten up by vice that virtue is abhorrent to them, and so inveterately dishonest that theft is to them a master passion. When a human being has reached that stage, there is only one course that can be rationally pursued. Sorrowfully, but remorselessly, it must be recognised that he has become lunatic, morally demented, incapable of self-government, and that upon him, therefore, must be passed the sentence of permanent seclusion from a world in which he is not fit to be at large.”

These very people, who are the worst part of the social problem, Booth will not trouble himself very greatly about. Here are a few extracts from the Rules for the “Colonists,” as he calls the people who come into his scheme.

(a) Expulsion for drunkenness, dishonesty, or falsehood will follow the third offence.

(b) After a certain period of probation, and a considerable amount of patience, all who will not work to be expelled.

(c) The third offence will incur expulsion, or being handed over to the authorities.

Expulsion is Booth's whip, and a very convenient one – for him! He will soon simplify his enterprise. All who come to him will be taken, but he will speedily return to society all the liars, drunkards, thieves, and idlers; so that when the scheme is in full swing, society will still have the old problem of dealing with the residuum, and in this respect Booth will not have helped in the least.

General Booth’s scheme is thus, in the ultimate analysis, merely one for dealing with the unemployed. On this point his ideas are simply childish. He seems to imagine that work is a thing that can be found in unlimited quantities. He does not suspect the existence of economic laws. It never occurs to him that by artificially providing work for one unemployed person he may drive another person out of employment. Nor has he the least inkling of the law of population which lies behind everything.

In his Labor Shops, in London, he proposes to make match-boxes. Well, now, the community is already supplied with all the match-boxes it wants. The demand cannot be stimulated. And every girl that Booth takes in from the streets and sets to making match-boxes, which are to be put on the market, will turn some other girl out of employment at Bryant and May’s or other match factories.

Similarly with the Salvation Bottles (p. 120) and the Social Soap (p. 136). Booth's soap, if it gets sold, will lessen the demand for other people’s soap, and thus a lot of existing soap-makers will be thrown out of work. If he collects old bottles, and furbishes them up “equal to new,” there will be so many less new bottles wanted, and a lot of existing glass-bottle makers will be thrown out of work. The wily old General of the Salvation Army, owing to a want of economic knowledge, falls into a most obvious fallacy. He is like the Irishman, who lengthened his shirt by cutting a piece off the top and sewing it on the bottom.

Getting hold of fish and meat tins, cleaning them up, and manufacturing them into toys, is hardly worth all the eloquence spent upon it by Booth’s literary adviser. Nor is there much to be said in favor of an Inquiry Office for lost people. If it be true that 18,000 people are “lost” in London every year, it may be assumed that the majority of them do not want to be found, and it is the business of the police to look after the rest. Neither is there any necessity to subvention General Booth to obtain workman’s dwellings out of town instead of ugly, dreary model dwellings in the midst of dirt and smoke. Nothing can be done until provision is made by the railway companies for conveying the workmen to and fro for twopence a day, and when this step is taken, as it must be, private enterprise will construct the dwellings without Salvation charity. With regard to the scheme of the Poor Man’s Bank, it would have been but fair to say that the idea is borrowed from infidel Paris, where for many years a benevolent Society has lent money to honest and capable poor men with gratifying results.

The giving of legal advice gratis to the poor would be a good thing if it did not lead to unlimited litigation. Of course General Booth does not say, and perhaps he does not know, that Mr. Bradlaugh has been doing this for twenty-five years. Thousands of poor men, not necessarily Freethinkers, have had the benefit of his legal advice. No one in quest of such assistance has ever knocked at his door in vain. Finally, with respect to “Whitechapel-at-Sea,” a place which Booth projects for the reception of his poor people when they badly need a little sea-air and sunshine, it must be said that this kind of charity has been carried on for years, and that Booth is only borrowing a leaf from other people's book. In fact, the “General” collects all the various charitable ideas he can discover, dishes them up into one grandiose scheme, and modestly asks for a million pounds to carry out “the blessed lot.”

Singly and collectively these projects will no more affect “the unemployed” than scratching will cure leprosy. Every effect has its cause, which must be discovered before any permanent good can be done. Now the causes of want of employment (if men desire to find it) are political and economical. The business of the true reformer is to ascertain them and to remove or counteract them. Pottering with their effects, in the name of “charity,” is like dipping out and purifying certain barrels of water from an everflowing dirty stream.

At the very best “charity” is artificial, and social remedies must be natural. Work cannot be provided. People have certain incomes and allow themselves a certain expenditure. If they give Booth, or any other charlatan, a hundred pounds to find work for “the unemployed,” they have a hundred pounds less to spend in other ways, and those who previously supplied them with that amount of commodities or service will necessarily suffer. Shuffle one pack of cards how you will, the hands may differ, but the total number of cards will be fifty-two.

General Booth talks infinite nonsense about the “failure” of Trade Unions because they only include a million and a half of workmen. Rome was not built in a day, and even the Salvation Army, with God Almighty to help it, is not yet as extensive as this “failure.” Nor does the world need Booth to tell it the benefits of co-operation. He looks to it as “one of the chief elements of hope in the future.” So do thousands of other people, but what has this to do with the Salvation Army?

The only part of Booth’s scheme which is of the least value is the one he has borrowed from a Freethinker. The Farm Colony is suggested by the Rahaline experiment associated with the name of Mr. E. T. Craig. But not only was Mr. Craig a Freethinker, the same may be said of Mr. Vandeleur, the landlord who furnished the ground for the experiment. At any rate, he was a disciple and friend of Robert Owen, who declared that the great cause of the frustration of human welfare was “the fundamental errors of every religion that had hitherto been taught to man.” “By the errors of these systems,” said Owen, “he has been made a weak, imbecile animal; a furious bigot and fanatic; and should these qualities be carried, not only into the projected villages, but into Paradise itself, a Paradise would no longer be found.”

The Rahaline experiment was a co-operative one, while Booth’s is to be despotic. He proposes to put the unemployed at work on a big farm, and afterwards to draft them to an Over-sea Colony, where the reformed “thieves, harlots, drunkards, and sluggards” are to lay the foundations of a new province of the British Empire. Something, of course, might be done in this way, but it is doubtful if Booth will get hold of the right material to do it with, or if his Salvation methods will be successful. Much greater effects than “charity” could realise would be produced by a wise alteration of our Land Laws, which would lead to the application of fresh capital and labor to the cultivation of the soil. It is, indeed, one of the prime evils of Booth's scheme, no less than of almost every other charitable effort, that it helps to divert attention from political causes of social disorders. No doubt charity is an excellent thing in certain circumstances, but the first thing to agitate for is justice; and when our laws are just, and no longer create evils, it will be time enough for a huge system of charity to mitigate the still inevitable misery.

So far we have discovered nothing original in General Booth's scheme. Its elements may be reduced to three. There is (a) the reformation of weak, vicious, and criminal characters, which is a rather hopeless task especially when the attempt is made with adults. Something might be done with children, and in this respect Dr. Barnardo’s work, with all its defects, is infinitely more sensible than General Booth’s. Then there is (b) providing labor for the unemployed, which, whether attempted by governments or charitable bodies is an economical fallacy. Finally there is (c) the planting of town populations on the land, which has a certain small promise of success if the scheme were to take the form of allotments to capable cultivators; but which, on the other hand, will surely come to grief if the experiment is made with even the selected residuum of great cities.

But supposing the scheme of General Booth were in itself full of social promise, a reasonable person would still ask, What are the qualifications of a religious body like the Salvation Army for carrying out such a scheme?

First of all, let us take the General. He plainly tells us he is to be the head of everything. He is not only to be the leader, but the brain; in fact, he expounds this function of his in a long passage of dubious physiology. Now, the General is undoubtedly a clever man.

But is he such a universal genius as to “boss” everything, from playing tambourines to making tin toys, from preaching “blood and fire” to the administration of a big farm, from walking backwards for Jesus to superintending a gigantic emigration agency? Unless he combines a vast diversity of faculties with supernatural energy, he is sure to come to grief; for absolute obedience to him is indispensable, and if hefails, the whole experiment fails with him.

Even if General Booth prove himself equal to the occasion, the despotic nature of the management makes the success of the scheme precarious. Everything hangs upon the single thread of his life, which may be snapped at any moment. Even if we admit his consummate and comprehensive genius, what guarantee is there that his successor will inherit it?

General Booth bids us remember that the Salvation Army has succeeded, and its past achievements are a pledge of its future triumphs. But let us look into this, and see how much it is to the point.

That the Salvation Army is a striking success is not to be disputed. But what is the character of its success? This is an all-important question: for a man, or an organisation, may be very successful in one direction, and hopelessly impotent in another.

Undoubtedly the Salvation Army caters for hysterical persons who are sick and tired of the “respectable” forms of religion. But is it true that the Army reforms the thief, the drunkard, and the profligate? Now in answering this question it is well to bear in mind that solitary cases prove absolutely nothing. There is no principle, no system, no organisation, which has not absorbed some persons who previously led lives of selfish indulgence, aroused in them an interest in impersonal objects, and surrounded them with a restraining public opinion. The real question is this – How is the Salvation Army in the main recruited?

Again and again it has been asserted by outsiders, and admitted by candid members, that the Army is principally recruited from other sects. Some years ago this assertion was publicly made in the Times by the Rev. Llewellyn Davies, who was prepared to prove it in his own parish of Marylebone. Mr. Davies was answered by “Commissioner” Railton, who indulged in vague generalities, which were cut short by the simple request to produce the notorious sinners converted in that parish. Of course they were not produced: for the most part these “converts” exist on paper.

The Army’s pretensions are disproved by statistics. It boasts of nearly ten thousand officers and a million of adherents. Now if these, or a considerable proportion of them, had been drawn from the moral residuum of England, a very serious impression would have been made on the ranks of vice and crime. But what are the facts? While the Education Act has made a difference in the number of young criminals, there is no perceptible diminution in the number of hardened offenders. Prostitutes, also, are as numerous as ever, and the national drink-bill actually increases.

Revival movements have always boasted of moral successes, but history shows that they make no real impression on the community. The method is unscientific and doomed to failure. A salvation meeting, with its noise and excitement, has as much effect on public morality as a savage’s tom-tom has upon the heavens. The noisy things in nature are generally futile. Whirlwinds and earthquakes affect the imagination, but it is the regular action of air and water that produces the greatest changes, and the gentle action of rain and sunshine that ripens the harvest. These “spiritual,” and nearly always hysterical, agencies for human improvement, are based upon a denial of the physical basis of life, and of the doctrine of moral causation. They attract great attention, and their leaders gain tremendous applause. But all the while the real work of progress is being done by other agencies – by the spread of knowledge, the growth of education, the discoveries of science, the silent triumphs of art, and the gradual expansion of the human mind. Agitation is not necessarily progress. What is wanted is a new ingredient, and that is furnished by the more obscure, and often lonely men, whose greatness is only known to a few, although their thoughts are the seed of future harvests of wisdom and happiness for the human race.

Suppose, however, we concede, for the sake of argument, all the claims of the Salvation Army as a religious agency of reform. This would afford a presumption of its continued success on the old lines. But the new lines are a fresh departure. General Booth himself admits that “the new sphere on which we are entering will call for faculties other than those which have hitherto been cultivated.” What guarantee has he then, beyond an unbounded and possibly exaggerated belief in himself, that those “faculties” will come when he “calls for” them? Will men of the required stamp of character and ability enrol themselves under the despotism of General Booth? And if they did, how long would he be able to hold them together? First of all, at any rate he has to get them. The ordinary Salvation Army captain is not equal to these things. This is obvious to General Booth; hence his fervid appeal to persons of greater capacity to throw themselves into his enterprise. But we do not believe he will obtain their assistance. It is far easier to extract a hundred thousand pounds, or even a million, from a gullible public, than to induce men and women of the stamp required in the successful conduct of a big social experiment to place themselves at the absolute command of a religious revivalist.

Let us now turn to a tremendously important aspect of General Booth’s scheme, which up to the present has been only alluded to. Lady Florence Dixie has pointed out, with her accustomed courage, that the scheme would, if successful, increase the pressure of population in the worst way by multiplying the unfit. Booth does not believe in celibacy, and we agree with him. But we are far from approving his idea of setting up a Matrimonial Bureau and bringing marriageable persons together. The marriages he is likely to promote will, of course, be chiefly among the classes he will try to reclaim. Such a prospect is anything but pleasant to those who understand the population question, and is quite appalling to those who understand the philosophy of Evolution.

When Archdeacon Farrar was preaching at Westminster Abbey on behalf of General Booth’s scheme, he made this observation: – “The country is being more and more depleted, the great cities are becoming more and more densely overcrowded, and in great cities there is always a tendency to the deterioration of manhood – morally, physically, and spiritually. Our population is increasing at the rate of a thousand a day, and the most rapid increase is among the destitute and unfit.” Precisely so; and it is among these very classes that General Booth, if he honestly means what he says, will do his best to promote an increase of population. In this respect his scheme involves a grave social danger. On the whole, it seems pretty plain, as Professor Huxley observes, that if General Booth does sixpennyworth of good, he will do a good shillings-worth of harm.