полная версия

полная версияMusic-Study in Germany, from the Home Correspondence of Amy Fay

But Weitzmann, the Harmony professor, is the funniest of all. He is the dearest old man in the world, and it is impossible for him to be cross; but he takes so much pains and trouble to make his class understand, and he has the most peculiar way of talking imaginable, and accents everything he says tremendously. I go to him because Ehlert says I must, but as I know nothing of the theory of music (and if I did, the names are so entirely different in German that I never should know what they are in English) it is extremely difficult for me to understand him at all. He knew I was an American, and let me pass for one or two lessons without asking me any questions, but finally his German love of thoroughness has got the better of him, and he is now beginning to take me in hand. At the last lesson he wrote some chords on the blackboard, and after holding forth for some time he wound up with his usual "Verstehen Sie wohl – Ja? (Do you understand – Yes?)" to the class, who all shouted "Ja," except me. I kept a discreet silence, thinking he would not notice, but he suddenly turned on me and said, "Verstehen Sie wohl – Ja?" I was as puzzled what to say as the Pharisees were when they were asked if the baptism of John were of heaven or of men. I knew that if I said "Ja," he might call on me for a proof, and that if I said "Nein," he would undertake to enlighten me, and that I should not understand him.

After an instant's consideration I concluded the latter course was the safer, and so I said, boldly, "Nein." "Kommen Sie hierher! (Come here!)" said he, and to my horror I had to step up to the blackboard in front of this large class. He harangued me for some minutes, and then writing some notes on the bass clef, he put the chalk into my hands and told me to write. Not one word had I understood, and after staring blankly at the board I said, "Ich verstehe nicht (I don't understand.)" "Nein?" said he, and carefully went over all his explanation again. This time I managed to extract that he wished me to write the succession of chords that those bass notes indicated, and to tie what notes I could. A second time he put the chalk into my hands, and told me to write the chords. "Heaven only knows what they are!" thinks I to myself. In my desperation, however, I guessed at the first one, and uttered the names of the notes in trembling accents, expecting to have a cannon fired off at my head. Thanks to my lucky star, it happened to be right. I wrote it on the blackboard, and then as my wits sharpened I found the other chords from that one, and wrote them all down right. I drew a long breath of relief as he released me from his clutches, and sat down hardly believing I had done it. I have not now the least idea what it was he made me do, but I suppose it will come to me in the course of the year! As he does not understand a word of English, I cannot say anything to him unless I can say it in German, and as he is determined to make me learn Harmony, it would be of no use to explain that I did not know what he was talking about, for he would begin all over again, and go on ad infinitum. I have got a book on the Theory of Music, which I am reading with Fräulein W. She has studied with Weitzmann, also, and when I have caught up with the class I shall go on very easily. I quite adore Weitzmann. He has the kindest old face imaginable, and he hammers away so indefatigably at his pupils! The professors I have described are all thorough and well-known musicians of Berlin, and I wonder that people could tell us before I came away, and really seem to believe it, "that I could learn as well in an American conservatory as in a German one." In comparison with the drill I am now receiving, my Boston teaching was mere play.

CHAPTER II

Clara Schumann and Joachim. The American Minister's. The Museum. The Conservatory. The Opera. Tausig. ChristmasBERLIN, December 12, 1869.I heard Clara Schumann on Sunday, and on Tuesday evening, also. She is a most wonderful artist. In the first concert she played a quartette by Schumann, and you can imagine how lovely it was under the treatment of Clara Schumann for the piano, Joachim for the first violin, De Ahna for the second, and Müller for the 'cello. It was perfect, and I was in raptures. Madame Schumann's selection for the two concerts was a very wide one, and gave a full exhibition of her powers in every kind of music. The Impromptu by Schumann, Op. 90, was exquisite. It was full of passion and very difficult. The second of the Songs without Words, by Mendelssohn, was the most fairy-like performance. It is one of those things that must be tossed off with the greatest grace and smoothness, and it requires the most beautiful and delicate technique. She played it to perfection. The terrific Scherzo by Chopin she did splendidly, but she kept the great octave passages in the bass a little too subordinate, I thought, and did not give it quite boldly enough for my taste, though it was extremely artistic. Clara Schumann's playing is very objective. She seems to throw herself into the music, instead of letting the music take possession of her. She gives you the most exquisite pleasure with every note she touches, and has a wonderful conception and variety in playing, but she seldom whirls you off your feet.

At the second concert she was even better than at the first, if that is possible. She seemed full of fire, and when she played Bach, she ought to have been crowned with diamonds! Such noble playing I never heard. In fact you are all the time impressed with the nobility and breadth of her style, and the comprehensiveness of her treatment, and oh, if you could hear her scales! In short, there is nothing more to be desired in her playing, and she has every quality of a great artist. Many people say that Tausig is far better, but I cannot believe it. He may have more technique and more power, but nothing else I am sure. Everybody raves over his playing, and I am getting quite impatient for his return, which is expected next week. I send you Madame Schumann's photograph, which is exactly like her. She is a large, very German-looking woman, with dark hair and superb neck and arms. At the last concert she was dressed in black velvet, low body and short sleeves, and when she struck powerful chords, those large white arms came down with a certain splendor.

As for Joachim, he is perfectly magnificent, and has amazing power. When he played his solo in that second Chaconne of Bach's, you could scarcely believe it was only one violin. He has, like Madame Schumann, the greatest variety of tone, only on the violin the shades can be made far more delicate than on the piano.

I thought the second movement of Schumann's Quartette perhaps as extraordinary as any part of Clara Schumann's performance. It was very rapid, very staccato, and pianissimo all the way through. Not a note escaped her fingers, and she played with so much magnetism that one could scarcely breathe until it was finished. You know nothing can be more difficult than to play staccato so very softly where there is great execution also. Both of the sonatas for violin and piano which were played by Madame Schumann and Joachim, and especially the one in A minor, by Beethoven, were divine. Both parts were equally well sustained, and they played with so much fire – as if one inspired the other. It was worth a trip across the Atlantic just to hear those two performances.

The Sing-Akademie, where all the best concerts are given, is not a very large hall, but it is beautifully proportioned, and the acoustic is perfect. The frescoes are very delicate, and on the left are boxes all along, which add much to the beauty of the hall, with their scarlet and gold flutings. Clara Schumann is a great favorite here, and there was such a rush for seats that, though we went early for our tickets, all the good parquet seats were gone, and we had to get places on the estrade, or place where the chorus sits – when there is one. But I found it delightful for a piano concert, for you can be as close to the performer as you like, and at the same time see the faces of the audience. I saw ever so many people that I knew, and we kept bowing away at each other.

Just think how convenient it is here with regard to public amusements, for ladies can go anywhere alone! You take a droschkie and they drive you anywhere for five groschen, which is about fifteen cents. When you get into the concert hall you go into the garde-robe and take off your things, and hand them over to the care of the woman who stands there, and then you walk in and sit down comfortably as you would in a parlour, and are not roasted in your hat and cloak while at the concert, and chilled when you go out, as we are in America. Their programmes, too, are not so unconscionably long as ours, and, in short, their whole method of concert-giving is more rational than with us. I always enjoy the garde-robe, for if you have acquaintances you are sure to meet them, and you have no idea how exciting it is in a foreign city to see anybody you know.

—BERLIN, December 19, 1869.I suppose you are muttering maledictions on my head for not writing, but I am so busy that I have no time to answer my letters, which are accumulating upon my hands at a terrible rate. This week I have been out every night but one, so that I have had to do all my practicing and German and Harmony lessons in the day-time; and these, with my daily hour and a half at the conservatory, have been as much as I could manage.

On Monday I went to a party at the Bancroft's, which I enjoyed extremely. It was a very brilliant affair, and the toilettes were superb. At the entrance I was ushered in by a very fine servant dressed in livery. A second man showed me the dressing-room, where my bewildered sight first rested on a lot of Chinamen in festive attire. I could not make out for a second what they were, and I thought to myself, "Is it possible I have mistaken the invitation, and this is a masquerade?" Another glance showed me that they were Chinese, and it turned out that Mr. Burlingame, the Chinese Minister, was there, and these men were part of his suite. The ladies and gentlemen had the same dressing-room, which was a new feature in parties to me, and as we took off our things the servant took them and gave us a ticket for them, as they do at the opera. I should think there were about a hundred persons present. There were a great many handsome women, and they were beautifully dressed and much be-diamonded and pearled. Corn-colour seemed to be the fashion, and there were more silks of that colour than any other.

Mr. Burlingame seemed to be a very genial, easy man. I was not presented to him, but stood very near him part of the time. He looks upon the introduction of the Chinese into our country as a great blessing, and laughs at the idea of it being an evil. He says that the reason railroads can't be introduced into China is because the whole country is one vast grave-yard, and you can't dig any depth without unearthing human bones, so that there would be a revolution on the part of the people if it were done now, but it will gradually be brought about. He travels with a suite of forty attendants, and says he has got all his treaties here arranged to his wishes, and that Prussia has promised to follow the United States in everything that they have agreed on with China. He is going to resign his office in a year and go back to America, where he wants to get into politics again. Mr. Bancroft introduced many of the ladies to the Chinese, one of whom could speak English, and he interpreted to the others. It was very quaint to see them all make their deep bows in silence when some one was presented to them. They were in the Chinese costume – Turkish trousers, white silk coats, or blouses, and red turbans, and their hair braided down their backs in a long tail that nearly touched their heels.

On Thursday I went to Dr. A.'s to dinner. He seems to be a very influential man here, and is a great favorite with the Americans. He has a great big heart, and I suspect that is the reason of it. Mrs. A., too, is very lovely. I saw there Mr. Theodore Fay, who used to be our minister in Switzerland, and who is also an author. He is very interesting, and the most earnest Christian I ever met. He has the tenderest sympathies in the world, and in a man this is very striking. He has a high and beautiful forehead, and a certain spirituality of expression that appeals to you at once and touches you, also. At least he makes a peculiar impression on me. There is something entirely different about him from other men, but I don't know what it is, unless it be his deep religious feeling, which shines out unconsciously.

Last week I made my first visit to the Museum. It is one of the great sights of Berlin, but it is so immense that I only saw a few rooms. In fact there are two Museums – an old and a new. I was in the new one. It is a perfect treasure house, and the floors alone are a study. All are inlaid with little coloured marbles, and every one is different in pattern. One of the most beautiful of the rooms was a large circular dome-roofed apartment round which were placed the statues of the gods, and in the centre stood a statue in bronze of one of the former German kings in a Roman suit of armour. Half way up from the floor ran round a little gallery in which you could stand and look down over the railing, and here were placed on the walls Raphael's cartoons, which are fac-similes of those in the Vatican, and are all woven in arras. They are very wonderful, and you feel as if you could not look at them long enough. The contrast is impressive as you look down and see all the heathen statues standing on the marble floor, each one like a separate sphinx, and then look up and see all the Christian subjects of Raphael. The statues are so cold and white and distant, and the pictures are so warm and bright in colour. They seem to express the difference between the ancient and the modern religions. We went through the rooms of Greek and Roman statues, of which there is an immense number, and on the walls are Greek and Italian landscapes, all done by celebrated painters.

We had to pass through these rooms rather hastily in order to get a glimpse of the "Treppen Halle," which is the place where the two grand stair-cases meet that carry you into the upper rooms of the Museum. This is magnificent, and is all gilding and decoration. An immense statue stands by each door, and on the wall are six great pictures by Kaulbach, three on each side. "The Last Judgment," of which you're seen photographs, is one of them. I ought to go to the Museum often to see it properly, but it is such a long distance off that I can't get the time. Berlin is a very large city, and the distances are as great as they are in New York.

At the last "Reading" at the conservatory the four best scholars played last. One of them was an American, from San Francisco, a Mr. Trenkel, but who has German parents. He plays exquisitely, and has just such a poetic musical conception as Dresel, but a beautiful technique, also. He is a thorough artist, and he looks it, too, as he is dark and pale, and very striking. I always like to see him play, for he droops his dark eyes, and his high pale forehead is thrown back, and stands out so well defined over his black brows. His expression is very serious and his manner very quiet, and he has a sort of fascination about him. He is a particular favorite of Tausig's.

After he played, came a young lady who has been a pupil of Von Bülow for two years. She plays splendidly, and I could have torn my hair with envy when she got up, and Ehlert went up to her and shook her hand and told her before the whole school that she had "real talent." After her came my favorite, little Fräulein Timanoff, who sat down and did still better. She is a little Russian, only fifteen, and is still in short dresses. She has almost white hair, it is so light, and she combs it straight back and wears it in two long braids down her back, which makes her look very childish. It is really wonderful to see her! She takes her seat with the greatest confidence, and plays with all the boldness of an artist.

Almost all the scholars in Tausig's class are studying to play in public, and I should think he would be very proud of all those that I have heard. There are many scholars in the conservatory, but he teaches only the most advanced. He only returned to Berlin on Saturday, and I have not yet seen him, though I am dying to do so, for all the Germans are wild over his playing. The girls in his class are mortally afraid of him, and when he gets angry he tells them they play "like a rhinoceros," and many other little remarks equally pleasing.

—BERLIN, January 11, 1870.Since my last letter I have been quite secluded, and have seen nothing of the gay world. I have been to the opera twice – once to "Fantaska," a grand ballet, and the second time to "Trovatore." The opera house here is magnificent, and I would that I could go to it every week. It is extremely difficult to get tickets to it, as the rich Jews manage to get the monopoly of them and the opera house is crowded every night. It is the most brilliant building, and so exquisitely painted! All the heads and figures of the Muses and portraits of composers and poets which decorate it, are so soft and so beautifully done. The curtain even is charming. It represents the sea, and great sea monsters are swimming about with nymphs and Cupids and all sorts of things, and one lovely nymph floats in the air with a thin gauzy veil which trails along after her. The scenery and dresses are superb, and I never imagined anything to equal them. The orchestra, too, plays divinely.

The singing is the only thing which could be improved. The Lucca, who is the grand attraction, is a pretty little creature, but I did not find her voice remarkable. The Berlinese worship her, and whenever Lucca sings there is a rush for the tickets. Wachtel and Niemann are the star singers among the men. Niemann I have not heard, but Wachtel we should not rave over in America. I am in doubt whether indeed the Germans know what the best singing is. They have most wonderful choruses, but when it comes to soloists they have none that are really great – like Parepa and Adelaide Phillips; at least, that is my judgment after hearing the best singers in Berlin, though as the voice is not my "instrument," I will not be too confident about it. Everything else is so far beyond what we have at home that perhaps I unconsciously expect the climax of all – the solo singing, to be proportionally finer also.

They have beautiful ballet-dancers here, though. There is one little creature named Fräulein David, who is a wonderful artist. She does such steps that it turns one's head to see her. She is as light as down, and so extremely graceful that when you watch her floating about to the enchanting ballet music, it is too captivating. There were four other dancers nearly as good, who were all dressed exactly alike in white dresses trimmed with pink satin. They would come out first, and dance all together, sometimes separately and sometimes forming a figure in the middle of the stage. Then suddenly little David, who was dressed in white and blue, would bound forward. The others would immediately break up and retire to the side of the stage, and she would execute a wonderful pas seul. Then she would retire, and the others would come forward again, and so it went. It was perfectly beautiful. Finally they all danced together and did everything exactly alike, though little David could always bend lower, and take the "positions" (as we used to say at Dio Lewis's,) better than all the rest.

On Friday I am going to hear Rubinstein play. I suppose he will give a beautiful concert, as he and Bülow, Tausig and Clara Schumann are the grand celebrities now on the piano, Liszt having given up playing in public. After our lesson was over yesterday, Ehlert took his leave, and left us to wait for TAUSIG – my dear! – who was to hear us each play. He came in very late, and just before it was time to give his own lesson. He is precisely like the photograph I sent you, but is very short indeed – too short, in fact, for good looks – but he has a remarkably vivid expression of the eyes. He came in, and, scarcely looking at us, and without taking the trouble to bow even, he turned on me and said, imperiously, "Spielen Sie mir Etwas vor. (Play something for me.)" I got up and played first an Etude, and then he asked for the scales, and after I had played a few he told me I "had talent," and to come to his lessons, and I would learn much. I went accordingly the next afternoon. There were two girls only in the class, but they were both far advanced. I had never heard either of them play before. The second one played a fearfully difficult concerto by Chopin, which I once heard from Mills. It is exquisitely beautiful, and she did it very well. From time to time Tausig would sweep her off the stool, and play himself, and he is indeed a perfect wonder! If, as they say, Liszt's trill is "like the warble of a bird," his is as much so. It is not surprising that he is so celebrated, and I long to hear him in concert, where he will do full justice to his powers. He thrills you to the very marrow of your bones. He is divorced from his wife, and I think it not improbable that she could not live with him, for he looks as haughty and despotic as Lucifer, though he has a very winning way with him when he likes. His playing is spoken of as sans pareil.

I spent a very pleasant Christmas. The family had a pretty little tree, and we all gave each other presents. It was charming to go out in the streets the week before. The Germans make the greatest time over Christmas, and the streets are full of Christmas trees, the shops are crammed with lovely things, and there are little booths erected all along the sidewalks filled with toys. They have special cakes and confections that they prepare only at this season.

CHAPTER III

Tausig and Rubinstein. Tausig's Pupils. The Bancrofts. A German RadicalBERLIN, February 8, 1870.I have heard both Rubinstein and Tausig in concert since I last wrote. They are both wonderful, but in quite a different way. Rubinstein has the greatest power and abandon in playing that you can imagine, and is extremely exciting. I never saw a man to whom it seemed so easy to play. It is as if he were just sporting with the piano, and could do what he pleased with it. Tausig, on the contrary, is extremely restrained, and has not quite enthusiasm enough, but he is absolutely perfect, and plays with the greatest expression. He is pre-eminent in grace and delicacy of execution, but seems to hold back his power in a concert room, which is very singular, for when he plays to his classes in the conservatory he seems all passion. His conception is so very refined that sometimes it is a little too much so, while Rubinstein is occasionally too precipitate. I have not yet decided which I like best, but in my estimation Clara Schumann as a whole is superior to either, although she has not their unlimited technique.

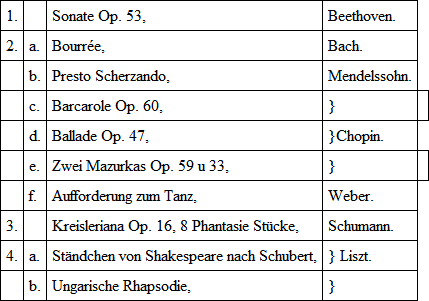

This was Tausig's programme:

Tausig's octave playing is the most extraordinary I ever heard. The last great effect on his programme was in the Rhapsody by Liszt, in an octave variation. He first played it so pianissimo that you could only just hear it, and then he repeated the variation and gave it tremendously forte. It was colossal! His scales surpass Clara Schumann's, and it seems as if he played with velvet fingers, his touch is so very soft. He played the great C major Sonata by Beethoven – Moscheles' favorite, you know. His conception of it was not brilliant, as I expected it would be, but very calm and dreamy, and the first movement especially he took very piano. He did it most beautifully, but I was not quite satisfied with the last movement, for I expected he would make a grand climax with those passionate trills, and he did not. Chopin he plays divinely, and that little Bourrée of Bach's that I used to play, was magical. He played it like lightning, and made it perfectly bewitching.

Altogether, he is a great man. But Clara Schumann always puts herself en rapport with you immediately. Tausig and Rubinstein do not sway you as she does, and, therefore, I think she is the greater interpreter, although I imagine the Germans would not agree with me. Tausig has such a little hand that I wonder he has been able to acquire his immense virtuosity. He is only thirty years old, and is much younger than Rubinstein or Bülow.