Полная версия

The Homing Instinct: Meaning and Mystery in Animal Migration

Cranes, like other large birds, grow slowly. It takes them thirty to thirty-two days to incubate their two eggs, and another fifty-five days for their (usually one) colt to be able to fly well enough to migrate. This far north there is only a narrow window of time for cranes to breed successfully, especially for those that fly even farther to breed, as some of those wintering in Mexico do, in Siberia. If late in arriving, they waste their effort of migrating the thousands of kilometers north. If they are too early, snow and ice cover all food sources. This year had been a winter of heavy snows in central Alaska. Even the boreal owls were starving from their inability to reach the voles under the snow. By late April, when I arrived, the woods around Millie and Roy’s home bog were still under at least half a meter of snow, and the cranes had not yet shown up.

I would have liked to fly with the cranes on their homeward journey, but the best I could do, apart from trying to beat them to their destination, was to see a piece of their flight path. My transcontinental flight of 3,872 kilometers from JFK Airport in New York was followed by a direct flight on April 23 from Seattle to Fairbanks, and I spent most of the three and a half hours of the 2,467-kilometer flight from Seattle north in the Boeing 737–800 with my face pressed to the window, trying to see like a crane. How did the cranes navigate and negotiate their five-thousand-kilometer journey from Texas or Mexico to come home to their own pingo out of thousands of others scattered throughout the vast and seemingly unending Alaskan taiga?

The cranes arrive lean at their main staging area, at the Platte River in Nebraska, and stay three weeks to gather reserves for their continuing journey north. When ready, they gather with thousands of others and wheel high in the sky into giant “chimneys,” to travel together on their common journey. Once in Alaska, they take separate paths to their individual homes, and a third of them fly beyond, to their homes in Siberia.

We had scarcely lifted off in Seattle when we passed over white-capped mountains with knife-edged ridges, dark forested valleys, and peninsulas surrounded by blue-gray water. An hour later, cruising at about eight hundred kilometers per hour at eleven thousand meters, there was ever more of the same — white mountains as far as the eye could see. Another hour — it was still the same. To me, barely a feature stood out from the jumble of endless peaks that melded into each other, and the vast mountain scape was broken only by frozen lakes glinting in the evening light. And so it continued for yet another hour. When we started our descent to Fairbanks, I saw oxbows of meandering rivers, and finally the thin thread of a road.

Cranes, swans, and geese travel south in the fall as family groups. On their way, the young learn the route they will later take north in the spring, to come back to try to settle near where they were born. What they see and remember seems astounding. I might, with intense concentration, memorize a tiny portion of the way, perhaps around this or over that mountain. But these cranes come not from my point of departure, the state of Washington, but from considerably farther south. (Four cranes from the Coldstream Valley that the Alaska Department of Fish and Game had equipped with radio transmitters ended up in various parts of Texas in the winter.) I could never retrace even my own much shorter flight route from Seattle, even if I were to return the day after having flown over it, much less a half-year later. What are the cognitive mechanisms that allow the birds to do this?

Day after day for almost eight months now there had been no crane at the pingo. For most of that time the ground had been under a deep layer of snow that locked any food out of reach. What would happen if, after their long-distance flying, the pair were to arrive at their home and find the bog still under snow and ice with no cranberries to be found and no voles to catch? How much can cranes afford to gamble in order to try to come on time, or even early?

It was only in the last week of April, after another snowstorm, that the weather suddenly warmed, and just then, on the 24th of April, on my first morning, we heard a crane in the distance. Still, no cranes landed on the pingo on the 25th, 26th, 27th. But the next morning at dawn I awoke to the loud and penetrating trumpeting calls of a single crane. These metallic sounds are unearthly; as Aldo Leopold wrote in his “Marshland Elegy,” they evoke “wildness incarnate.” On and on this bird shattered the dawn’s stillness, and I ran out to look. But the bird was then distant, and the sound kept shifting position, so I presumed it was flying around in great circles, possibly looking for a patch of cleared ground; the mossy floor of the nearby stunted spruce forest was still covered in deep snow.

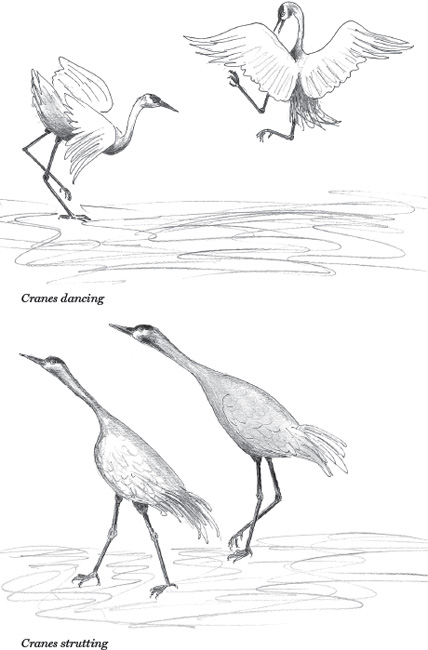

That evening we sat down to supper by the window facing the wide-open panorama of the pingo in front of us. The sun was still high. We were just polishing off the last of our freshly grilled salmon when we looked up to see a crane with spread wings gliding down for a landing. Its long thin legs touched down gently on the still-thick ice of the pond. It bugled and sprang up half a meter or so, unfurling its long neck with beak held skyward and with extended wings at the apogee of its graceful leap as if to catch itself in the air to prolong this moment. It looked like a physical embodiment of joy and excitement. The crane kept leaping, all the while continuing its stirring bugling. Cranes don’t do this every time they land; this was indeed a special landing. Finishing its dance, the crane started to walk in a contrastingly slow and deliberate manner, thrusting its head forward and up with each step, and at the same time opening its bill and making a very different, trilling, call.

The crane walked and leaped in several more repetitions of its dance before eventually lifting off with even wing beats to sail off in the same direction from which it had come, its haunting cries growing faint in the distance. Two hours later the (same?) crane came again, but this time it circled the bog only once before leaving, continuing its calling. It had given the impression that it was glad to be back but was at the same time agitated and looking for something; a mate? In previous years Millie and Roy had always returned as a couple, George and Christy told me, so lacking positive identification, we were skeptical that this was either of them.

I had barely gone to bed that night when I heard another one or possibly two cranes calling excitedly, while a third seemed to answer from the distance. I jumped up and rushed outside to look: a pair were walking from one end of the bog to the other. George and Christy were up also, and for the next hour, until it got dark at 11:15 p.m., we watched. One of the cranes stood tall and extended his head and neck forward and up, reminding me of the dominance display of a male raven. This was Roy. The second one, whom I would soon identify by her walk and talk and narrower white face patch, held her neck and head in a more downward curve like a heron’s, projecting her head slightly forward with each step. She started to pick up cattail fronds and grasses and then to deposit them, sitting down briefly on the materials. Was she encouraging her mate by suggesting to him that it was time to start nesting at one or another of these potential nest sites? I could hardly wait to see what would happen next.

Crane pair coming home

Another clamor awoke me in the early dawn, around 4:00 a.m. There had been a heavy overnight frost and the two cranes were standing on the ice in the middle of the bog. Both Millie and Roy tossed their heads up in a quick motion, their bills opening wide during each call. We heard what sounded like a hammer hitting a metal bell or drum, as he opened his bill once to make each call and she chimed in at the same time but called and opened her bill twice to make two short similar cries of a higher pitch. It was a composite call made by both together; a duet. A third, distant crane responded. The distant calls, and the pair’s duet, were repeated back and forth, often and loudly.

The vigor of the pair’s unison calling was still palpable, even when the first morning light lit the sky and silhouetted the black spruces, and when I thought about the enormous effort they had invested to get here, I realized what was at stake: home ownership. The pair’s loud clanging calls attracted no others flying in from the distance; instead, the calls are a vocal “no trespassing” sign, one leaving no doubt that any potential challenger would be facing not just one bird, but a united, cooperating pair.

I watched the pair for another hour. She by then occasionally fluffed herself out and, as she had done the day before, continued periodically to squat where she had pulled at or dropped sedge and other potential nesting material.

The pair continued their slow, deliberate steps that morning while meandering from one end of the bog to the other, as though inspecting every square centimeter of it, and at 9:00 p.m. we saw Roy jump high and with outstretched wings dance by himself out on the ice. Millie dashed by him with fluttering wings, to round out a mutual performance. A little later we heard a purring call as she spread her wings to the sides and stood still. Roy, with outstretched neck and elevated bill, jumped onto her back and, balancing himself with a few wing beats, mated. He dismounted after a couple of seconds. Both then bowed to each other and continued their walk. They were home, intended to nest, and had now sealed the deal.

Still, the lone bird that had tried to intrude on their turf did not easily abandon its intended claim. But why would this crane want a claim without a mate to nest with? Was it Oblio, their grown colt from last summer? Was he, now that Millie and Roy were re-nesting, finally being “thrown out of the nest” by his parents, who no longer tolerated company of any sort? I suspect this was the case. The offspring of most birds have a strong attachment to home. This emotion is a biologically relevant drive, because home is where reproduction has proven to be successful. But the young have a lifetime ahead of them, and if for some reason the parents don’t make it back home, the offspring could inherit their territory. If the parents do come back to reclaim their home, at least nearby territory would be more like the old home than the far-off unknown. Even if a bird is without a mate, finding a suitable territory is often a prerequisite to getting one.

Shortly after we had breakfast the next morning, the lone crane flew over once again, and the pair immediately launched their synchronized duet as a vocal challenge. This time, although the lone crane did not land, the pair jumped into the air and chased it until all three were out of our sight and hearing. But the pair returned soon and then again performed several nest-building probes. They again mated in what would become a routine for the next several days: at least once in the morning and once in late afternoon or at night.

When I first saw the cranes the next dawn, each was standing on one leg with its head tucked into its back feathers. Ice had again solidly covered their pond, after having partially melted along the edges the day before. Both Millie and Roy seemed to be asleep, although he, balancing himself on one leg, occasionally reached up with the other to scratch his chin and head with the toes of the foot. But whenever a crane called from the distance, both their heads shot up instantly, and they renewed their spirited in-unison call, she making the two short notes and her mate making one, at a lower pitch.

We had so far not seen them feed. Indeed, it was hard to imagine that there was food available in any case. If lucky, they might by now catch a vole or find a few of last year’s cranberries, but this year that would probably not be likely until days later when the snow would melt. A crane’s large body size requires much more food than a small bird’s, but that same large size is an advantage in tiding them over during lean periods, and thus to return to their homes before the anticipated flush of food becomes available.

As it got lighter on this dawn, the cranes soon had company. A pair of swans and then a small flock of five Canada geese flew by. A robin sang. By about 7:00 a.m., the crane pair became animated as well, walking over the bog while picking here and there, and again mating.

We did not see the pair most of that afternoon. The lone crane, seemingly to take advantage of their absence, again flew in and this time landed, looked around, and repeatedly made a trilling call. But in about fifteen seconds the pair flew in as if out of nowhere, and one of them sped over the ice as if to attack the interloper, which immediately flew off. The pair gave chase, and all three disappeared from sight. In several minutes the single bird returned. Again the pair came and caught up to the lone crane before it had a chance to take off, and this time they attacked it viciously, in a flurry of flailing wings.

The pair had by now, after the third day, won the major part of the battle. Barring accidents, they would within days lay their two eggs and go on to raise their colt. Normally both eggs hatch, but as in some eagles and vultures, usually only one chick survives, probably because one gets fed less and then weakens and eventually starves. Presumably through evolutionary history, for the fast growth required to reach full development and readiness to migrate by August, there has not been enough food to raise two colts at once. One might suppose the cranes could simply lay only one egg, but sometimes an egg does not hatch, and the second is insurance.

The pair seemed more animated after their last fight with the lone intruder, and by evening they again mated (for at least the third time that day). In most birds one mating is enough to fertilize the eggs. Perhaps several matings are insurance, but this seemed more than enough for insurance. Perhaps, like their dances, mating is additionally part of their bonding ritual.

A pair of mallards, and then a pair of pintails, arrived in the evening, and the ducks swam next to each other near the cranes at the edge of the pond, where some open water had reappeared during the day. The cranes ignored them and again walked in their stately manner back and forth across the ice of the pond, and now they pecked in the low vegetation being exposed along the edges. They were by now finding overwintered cranberries exposed by the melting snow.

On the evening before I would leave for my journey home, Christy and George hosted a potluck party. Shadows fell on the white frozen middle of the pingo as the western sky turned yellow and orange and the spruces became dark silhouettes. A pair of pintails again landed in the open water along the pond’s edge. The cranes were standing, each on one leg, their heads tucked into their back feathers. People crowded around the spotting scope in the living room, watching them occasionally shift position, lower a leg, poke a head out to look around. Suddenly the person then at the scope erupted with an exclamation: “They are mating!” She had seen the male approach the female with her spread wings, mount, flutter, and jump off. The pair had bowed to each other. Suddenly many people crowded around the scope to watch.

Why, I wondered, would anyone, or almost everyone, want to watch cranes mate? Why was nobody interested in watching the mating activity of the two ducks, or of the numerous redpolls? Could it be, I wondered, because we feel a closer kinship with cranes than with other birds?

Cranes are similar to us in many ways. Some are nearly as tall as a person. They walk on two long legs like us, albeit with a much more graceful and deliberate gait, so that they remind one of a caricature of a gentleman or an elegant woman on a leisurely stroll. The sandhill crane’s red bald pate and sharp yellow eye add to the caricature. Cranes form lifelong pairs and stay together as families, but they are also gregarious and join up into large groups. They form a strong attachment to their home. They not only make music with trumpeting calls that sound like bugles, but they also dance, and do so on various occasions.

All of the fourteen species of the world’s cranes dance. Crane dancing involves running, leaping into the air, flapping the wings, turning in circles, stiff-legged walking, bowing, stopping and starting, pirouetting, and even throwing sticks. Dancing is primarily done by pairs and presumably functions in cementing pair bonds and/or synchronizing reproduction. But it can also be induced at any time, and it stimulates other cranes to dance. Even the young colts perform some of the species’ dance. Possibly it serves as practice and could be motivated by the same basic emotions of joy that are an indicator of health important to mating.

Cranes’ dances often stimulate humans to dance as well and have been mimicked in many cultures all over the world where cranes live. Crane dances were performed by ancient Chinese, Japanese, southern African, and Siberian people. If not emulated, cranes are admired. In the Blackfoot tribe of Native Americans of northern Montana, the last name “Running Crane” is common.

Nerissa Russell, an anthropologist, and Kevin McGowan, an ornithologist from Cornell University, revealed that eighty-five hundred years ago at a Neolithic site in what is now Turkey, people probably performed crane dances using crane wings as props that were laced to the arms. Furthermore, someone of these people apparently hid a single crane wing in a narrow space in the wall of a mud-brick house along with other special objects (a cattle horn, goat horns, a dog head, and a stone mace head). Russell and McGowan also found evidence that vultures may have been hunted for their feathers for presumably a much different costume worn as well for a ceremonial purpose. The authors inferred that the cranes were linked with happiness, vitality, fertility, and renewal (since they arrived in the spring). While the crane dance was one of life and birth, and possibly marriage and rebirth, the vulture dance was associated with death and perhaps return to the afterlife.

Russell and McGowan believe that the crane wing interred in the wall of the house was never intended to be seen. It was a symbolic object related to marriage and construction of a new home and may have been coincident with a particular human marriage and home-making. The associations among dancing, pairing, and raising young and home would have been natural for people who saw cranes return to their home ground, just as I had seen Millie and Roy do. Seeing the close parallels in the biology of the birds with their own lives, and understanding the cranes’ dancing as helping to make or cause the good things that followed, Neolithic people would have been compelled to symbolically emulate the crane dance of homecoming and of new life.

BEELINING

Observation sets the problem; experiment solves it, always presuming that it can be solved.

— Jean-Henri Fabre

CRANES FLY AN ENORMOUS DISTANCE TWICE ANNUALLY, BUT relative to their size, bees also fly huge distances — up to ten kilometers — and the foragers may perform such trips hourly. We can experiment with them to find out how they navigate. What we know about bee homing so far is nothing less than astounding, and it is built on a long history of research, primarily pioneered by the imaginative experiments dreamed up and performed by an Austrian named Karl von Frisch and his colleagues that date back over a half-century. Arguably, our knowledge dates back still further to early American frontiersmen trying to find bees’ treasure troves of honey.

In 1782, Hector St. John Crèvecoeur, a writer and farmer from Orange County in New York State, wrote:

After I have done sowing, by way of recreation, I prepare for a week’s jaunt in the woods, not to hunt either the deer or the bear, as my neighbors do, but to catch the more harmless bees … I proceed to such woods as one at a distance from any settlements. I carefully examine whether they abound in large trees, if so, I make a small fire on some flat stones, in a convenient place; on the fire I put some wax; close by this fire, on another stove, I drop honey in distinct drops, which I surround with small quantities of vermillion, laid on the stones; and I retire carefully to watch whether any bees appear. If there are any in the neighborhood, I rest assured that the smell of burnt wax will unavoidably attract them; they will find the honey, for they are fond of preying on that which is not their own; and in their approach they will necessarily tinge themselves with some particles of vermillion, which will adhere long to their bodies. I next fix my compass, to find out their course — and, by the assistance of my watch, I observe how long those are returning which are marked with vermillion. Thus possessed of the course, and, in some measure the distance, which I can easily guess at, I follow the first, and seldom fail of coming to the tree where those republics are lodged. I then mark it [presumably with his name to claim ownership].

James Fenimore Cooper, author of the Leatherstocking Tales of the American frontier, of which The Last of the Mohicans is probably best known, in 1848 published the novel The Oak-Openings; or, The Bee-Hunter. Here Cooper depicts a different, perhaps more reliable method than Crèvecoeur’s of the frontier activity that came to be called “beelining.” Cooper’s story takes place during July 1812, in the “unpeopled forest of Michigan,” where, due to the Native Americans’ lighting periodic fires to clear the ground, there were many flowers among the scattered oaks. This was ideal honeybee habitat, and here the bee hunter Benjamin Boden, nicknamed “Ben Buzz,” practices his art. Ben captures a bee from a flower by placing a glass tumbler over it and sliding his hand underneath. He then places the tumbler with the captured bee on a stump next to a piece of filled honeycomb. He puts his hat over the tumbler and the honeycomb so the bee will not be able to escape. He waits as the bee, stumbling around in the dark, eventually finds the honey. Once it is preoccupied with imbibing the honey, it quits buzzing, and the silence is the signal for Ben to remove the hat and then the glass, as the bee will stay to finish its feast and will fly up, circle the honeycomb, and depart directly toward its nest. He then follows the bee to the tree, chops it down, and is rewarded with just over one hundred kilograms of honey. Easier said than done.

American honey hunters eventually added refinements to their beelining techniques. The main improvement was the invention and use of a “bee box,” a small wooden box designed to catch a bee and get it “drunk” on a hunk of honeycomb. It was used in Maine when I was a kid (I still own mine). George Harold Edgell, a lifelong bee tree hunter from New Hampshire, wrote in 1949 in a pamphlet titled The Bee Hunter that “one’s first task is to catch a bee and paint its tail blue” and “this must be done gently [because] bees do not like to be painted. To paint a bee, it is best to wait until it is eagerly sucking up a thick sugar syrup and is too pre-occupied to notice.”

By 1901 Maurice Maeterlinck, the Belgian playwright and Nobel laureate in literature, described in The Life of the Bee his scientific experiments on bees that were individually identified with daubs of paint, from which he deduced that these insects could communicate their discoveries of food bonanzas to hive mates that would then navigate directly to the food. However, American woodsmen not only had used similar methods, but had also, through their beelining, already gleaned that same surprising insight into what the bees could do. Maeterlinck credited his American predecessors for their discoveries and wrote, “The possession of this faculty [to communicate food locations to hive mates that then can navigate to the food] is so well known to American bee hunters that they trade upon it when engaged in searching for nests.”