полная версия

полная версияJimmy Kirkland and the Plot for a Pennant

Baldwin hesitated as if thinking how best to state his case, and Clancy eyed him closely, feeling that the real object of the interview was coming, "I'm not at all pleased with the way you are working your pitchers."

"A fellow makes blunders sometimes," replied Clancy, with a meekness astounding in him.

"That's what I wanted to talk to you about," went on Baldwin blandly. "Who do you propose pitching to-day and to-morrow?"

In a flash Clancy understood. It was Baldwin who had been urging Bannard to have Williams pitch. He saw through Baldwin's motives and planned quickly how to meet them.

"Well," he said, frowning as if worried, "it's a tough game. You see, the fans never forgive a fellow if he guesses wrong at this time in a race. I planned to use Williams in one game and Morgan the other. You see the Blues hit right-handers harder than they do left-handers."

"So I understand," a gleam of cunning and triumph came into the eyes of the politician. "Morgan and Williams ought to beat them, I think."

"Yes, they ought – I'm a little afraid of Morgan." Clancy was drawing the owner out. "He hasn't shown speed in his last two games."

"Then Williams is in fine form?" The triumph and satisfaction in the big man's voice were unmistakable.

"He's good," replied Clancy. "He ought to best them sure."

"Will you pitch him to-day or to-morrow?" asked Baldwin, completely thrown off his guard. "I'm anxious to make certain he will pitch."

"Of course he'll pitch, Mr. Baldwin," replied the manager. "I've got to pitch him and he's my best man."

"All right, Clancy, all right," said the owner genially. "I'm glad I had this conference with you. I was afraid you were angry with Williams or something and would not let him work. Glad to see you have good judgment."

He went out and as the door closed he removed his hat, and, wiping his brow, smiled a smile of great relief over the fact that his purpose had been accomplished without trouble. Had he been able to see through the door he would have seen Clancy, the veins of his neck standing out purple, his face convulsed with rage, standing, shaking his fist toward the door and muttering:

"Yes, I'll pitch Williams. I'll pitch Williams, and by – he'll win."

CHAPTER XXVII

Searching

Betty Tabor had remained at the hotel in the home town with Mrs. Clancy when the Bears went to play their two-game series with the Blues.

Mrs. Clancy had refused positively to engage in any baseball conversation or to debate with Miss Tabor the chances of the Bears winning the championship.

"Heavens knows it's hard enough to be married to a baseball man," she said as she bit a thread, "him makin' base hits in his sleep and worrying the little hair he has left off his head, without havin' a girl that ought to be thinkin' of dresses and hats wantin' to din baseball into my ears all day. My dear, never marry a ball player."

"You appear to be pretty well satisfied with yours, Mother Clancy," teased the girl. "Maybe I'll find one as fine some day" —

"I'm thinkin' you've found yours now," replied Mrs. Clancy, without glancing up from her work. "A nice bye, too, although they do say the red-headed ones are hot tempered."

"Why, Mother Clancy! How dare you!" the girl expostulated, reddening.

"If you're thinkin' to deceive Ellen Clancy, you're sore mistaken," replied the manager's wife. "My Willie says I can tell when young people are in love before they know it themselves, an' ye and the red-headed McCarthy boy has all the symptoms. 'Tis a nice boy he is, too, and you'll be doin' well."

"But after ye've been married as long as we have ye'll not be wantin' to see many ball games. Many's the time I've begged Willie to quit it and get a little house out in the country, with a bit of green grass and maybe a flower bed and a little garden and a porch, and maybe a chicken yard, and let me end my days in peace, out of the sound of crowds and yellin' maniacs. Eighteen year I've ridden with him on cars smellin' of arnica, and with the train dust an' cinders in me eyes an' hair, and I long for peace. Only one season I've missed – 'twas when little Mar-rtin was born" —

She snuffled a little and dropped her work to wipe her eyes hastily. It was fifteen years since their only baby had come and gone in a short year, to leave them closer to each other, but each with a heart pain that never ceased.

A bell boy interrupted her lecture to bring in a card, and Mrs. Clancy, glancing at it, passed it over to Miss Tabor.

"'Tis for you, Betty girl," she said. "And, Mother of Mary, she'll see us this way" —

Betty Tabor sat staring at the card, at first puzzled, then in a panic of mingled emotions.

"Tell her to come up," she said. "I'll see her here. Mother Clancy, don't you dare hide."

The girl hastily arranged her hair and straightened the room, and a few minutes later, when the boy ushered the visitor into the apartments, she was self-possessed and cool. She arose as the door opened, and started forward to meet her guest, but stopped staring as the color faded from her face and then slowly heightened.

"You are Miss Tabor?" inquired the visitor, her voice trembling from excitement and nervousness.

"Yes. You are Miss Helen Baldwin; you desired to see me?"

The sight of the girl she had seen talking with Kohinoor McCarthy in the hotel parlor, shortly after he joined the club, had shaken her composure.

"Oh, Miss Tabor," Helen Baldwin cried, sinking into a chair and giving way to her emotions. "I had to come – I had nowhere else to go – and they told me over the telephone only you and Mrs. Clancy were here and all the men of the team away."

"If it is baseball business," replied Miss Tabor, "perhaps you'd better see Mrs. Clancy. I'll call her" —

"No! no! no!" expostulated the girl, drying her eyes. "It is you I must see. Have you heard anything from Mr. McCarthy?"

"I have no especial reason to hear from Mr. McCarthy," said Miss Tabor, freezing slowly. "I suppose he is with the team."

"He isn't! He isn't!" pleaded the girl. "He has disappeared – Haven't you seen the papers?"

"Mr. McCarthy disappeared! Where? When?" Betty Tabor had forgotten her jealousy in her startled alarm. "He isn't with the team?"

"I read it in the papers," sobbed Helen Baldwin. "He was at my house last evening. He left there – and he has disappeared. I hoped you might know."

"At your house?" Betty Tabor's alarm struggled with her jealousy. "And he's gone? Let me see the paper."

"I haven't seen him, Miss Baldwin," she said, after glancing at the paper. "We thought he had gone with the team. Tell me what you know. Perhaps we may help you. You were engaged to him, were you not?"

"We were – once," sobbed Helen Baldwin. "But that's all over. I did him a wrong. I never loved him – that way – and it's all my fault he's in trouble now."

Betty Tabor's heart leaped with a joy that overwhelmed all other emotions. Her cold attitude toward Helen Baldwin changed, and, sinking upon the seat beside the sobbing girl, she put her arm around her.

"There, there," she said comfortingly, as a mother might, forgetting that Helen Baldwin was older that she. "You must not blame yourself. Try to tell me what happened last evening. Perhaps we may know what to do."

Slowly, with interruptions by hysterical moments, Helen Baldwin told the story of her unconscious part in the conspiracy; of her alarm for the safety of McCarthy; how she had sent for him and warned him, and of Swanson's telephone call.

"You'd better go home, dear, and rest," Betty said finally. "There is nothing we can do. The men will have started the search early this morning and notified the police. He will return."

Helen Baldwin, calmed and reassured by the brave pretense of the younger woman, prepared to go home. Betty Tabor assisted her to rearrange her disordered fair hair, murmuring her admiration for it as she worked. For the first time a smile came to the troubled face of Helen Baldwin, and when she was ready to go she kissed Betty and held her at arm's length.

"You're very good and unselfish," she said in low tones. "I hope you and he are very happy."

"Why, Miss Baldwin," exclaimed Betty, blushing, "there is nothing between us. He is scarcely a friend" —

"I know, dear," replied the taller girl, kissing her again. "He is a very good and lovable boy, and very impetuous. He really loves you."

She smiled a trifle wanly and turning, left the room.

Betty Tabor turned with a sigh, just in time to see Mrs. Clancy making violent gestures through a small crack in the door.

"You didn't ask her," exclaimed the exasperated Mrs. Clancy. "You didn't ask her!"

"Ask her what?" inquired Betty in surprise. "You heard what we talked about?"

"Every word. I listened shamelessly," replied the manager's wife. "'Tis my curiosity will kill me. You didn't ask her one word about who McCarthy is. And she knows all about him!"

"I didn't think – I forgot," said Betty, hurrying to gather her work and belongings in preparation for leaving.

"Where are you going, child?" asked Mrs. Clancy.

"I'm going to dress and get an automobile to make the rounds of all the hospitals. He may be hurt and in one."

"Glory be! I never thought of it! Dress fast, darlin', an' I'll go with you."

They returned, weary and discouraged. They had not found a trace of the missing boy. Scarcely had they reached their rooms than another call for Miss Tabor came, and a few minutes later Technicalities Feehan entered.

"Mr. Feehan, what are you doing here?" both women exclaimed in chorus.

"I'm searching for Mr. McCarthy," responded Feehan. "I reached the city shortly after five o'clock, and, having concluded my arrangements for finding Mr. McCarthy, it occurred to me that, having an evening of idleness, I might devote it to no better purpose than in escorting you ladies to some place of amusement."

"To a theatre, with a tragedy like this happening to one of our boys!" exclaimed Miss Tabor indignantly.

"Rest assured, Miss Tabor," he replied, "we can do nothing, and eventually Mr. McCarthy will be found."

"How? Who is looking for him while we waste time?" she asked hotly.

"My arrangements," he stated quietly, "did not include useless running around. I called upon our managing editor, laid the figures and conclusive data before him, and convinced him that, besides securing an excellent news story, he can serve the team and the ends of right and justice by seeking Mr. McCarthy."

"Well, what did he do?" demanded Mrs. Clancy, sadly out of patience with his deliberate manner and rather flamboyant style of expression.

"As a result of his interest in the matter," replied Technicalities, "eight of the most highly trained men of his staff – men who know the city better than anyone who lives in it does – are seeking Mr. McCarthy with orders to find him to-night."

"How did to-day's game come out?" inquired Miss Tabor, relieved. "I almost forgot the game."

"Our team was defeated, 8 to 6," replied Feehan quietly. "McCarthy's absence already has cost us one game, and I greatly fear that unless he plays to-morrow the Bears are defeated in the championship contest."

"Glory be! I've dropped two more stitches!" said Mrs. Clancy.

CHAPTER XXVIII

Williams Stands Exposed

"Now here's a bally nice mess of figures," said Kennedy, holding half a dozen much-marked-upon sheets of writing paper in his inky fingers, and looking across the table at Swanson, Norton and Holleran.

"What are you figuring, Ken?" asked Holleran.

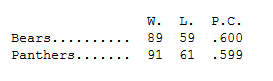

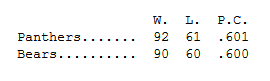

"I've been trying to figure out this pennant race," said Kennedy irritably. "Here we seem to be half a game ahead of the Panthers, and yet, just because it rained on them yesterday, and they didn't have to play but one game of their doubleheader, we've got to win two games to beat them out if they win their one game to-day."

He handed across a sheet of paper upon which was written:

"Well, ain't we ahead of them?" asked Swanson, studying the figures.

"Yes, but look here. Supposing they win to-day and we win, we'll still be ahead. But supposing they win to-day and we win, and then we lose to-morrow. Look at this."

He handed over another slip of paper, upon which was written:

"If we don't win both these games, or if it don't rain here to-day, or up home to-morrow, and keep us from playing, they beat us out by ten thousandths, or thirteen hundred thousandths. Didn't I always say thirteen was an unlucky number?"

"I wonder who Clancy will send in to pitch to-day?" asked Kennedy, idly. "Wilcox hasn't had enough rest. I suppose he'll be saved for to-morrow. Jacobson isn't right, and Morgan worked yesterday and got his trimmings. I suppose it'll be Williams."

An ugly laugh greeted his sarcastic remark, and Norton opened his lips as if to speak, but, thinking better of it, closed them again.

At that moment a bell boy came into the writing room, paging Williams. A quick exchange of glances between the players resulted and Swanson asked, "Who wants Mr. Williams?"

"Mr. Clancy, sir," said the boy. "He wants Mr. Williams in his room at once."

"Didn't I tell you?" said Kennedy, in mock triumph.

"Say, fellows," added Swanson. "I'd give a month's pay to hear what comes off up in that room. Clancy was on his ear this morning when I came down. He'd been awake half the night, trying to get some word from Kohinoor, and he was pretty well worked up. You know when he gets started to telling a fellow what he thinks of him he does it so the fellow believes it himself."

"He sure can explain a fellow's shortcomings," said Kennedy. "Look, the boy has found Williams and he is going up. He looks scared to death."

"Mamma, but I'd like to be among those present," said Swanson. "There will be several developments. Hadn't we better put mattresses under Clancy's window for Williams to light on?"

Meantime, in Manager Clancy's room a scene was being staged that fulfilled all the expectations of the players. Williams entered the room with a swaggering pretense of ignorance of the nature of the summons.

"Morning, Manager," he said with an effort at innocent playfulness. "How's things?"

"Sit down, you crook!"

Clancy had arisen as Williams entered. He shot the order at the pitcher viciously and without warning, and, as he spoke, he stepped past the player, and locked the door.

Williams had gone pale. His mouth dropped open. He started to say something, choked and sat down.

"What – what do you mean?" he managed to stammer as Clancy came close and stood over him threateningly.

After his first outburst of rage Clancy was strangely quiet, speaking in low tones, vibrating with repressed feeling. From the moment Barney Baldwin had revealed to him his ownership of the Bears, and had issued his positive orders that Williams should pitch the game, Clancy had been fighting within himself, studying to find some plan of vengeance that would strike all the plotters. Never for an instant had he considered the thought of permitting the championship to be surrendered by the orders of the owner.

"Williams," he said, "you're a never-to-be-sufficiently-spit-upon cur. You're the lowest, yellowest dog in the world. I've known for two weeks that you have been trying to lose the pennant for us."

"Shut up!" he snapped, lifting his voice sharply as the pitcher attempted to speak. "I know what you've done and what you plan to do. I know who is back of you" —

The pitcher cowered under the scathing denunciation and started as if to rise.

"Who – who's been telling you this stuff?" he quavered, terror-stricken.

"You – you rat." Clancy's scorn stung like a lash and Williams quivered. "I know everything. I've waited and watched when you thought you were putting something over. I've waited for a chance to get you" —

He paused a moment, while Williams, palsied with terror, sat unable to answer.

"And I've got you, Williams!"

He shot the sentence at the pitcher, who half started from his seat, lifting his hands as if to protect himself from attack.

"I'm not going to choke you to death, I wouldn't soil my hands on you," said the manager with a scornful laugh.

"What are you going to do, Bill?" William's voice quivered.

"I'm going to make you pitch to-day's game," said the manager quietly.

A gasp of amazement and relief came from Williams.

"You're going to pitch to-day's game, Williams," the manager repeated. "And you're going to win it. You're going to win it, or if you don't win I'll tell the crowd you were bribed, and I'll let the crowd handle you. They'll tear you to pieces, Williams, and kick the pieces around the diamond – and I'll help them do it."

"You won't do anything to me if I win?" pleaded the pitcher.

"No; I won't do a thing to you," said Clancy, and he spat as if to relieve himself of a bad taste, as he turned and went out, locking the door.

"Good God, look at Clancy," whispered Swanson in awed tones as the manager stepped out of the elevator a minute or two later. "He's in his blackest form. I honestly pity Williams."

"Swanson," said Clancy sharply.

"What is it, Boss?" asked Swanson anxiously.

"Nothing," snapped Clancy, "I want you to do something."

"All right."

"Williams is locked in my room. You watch the door. If he breaks out kill him."

He turned and stalked away like a man in a trance, leaving the big shortstop staring after him.

CHAPTER XXIX

Found

Technicalities Feehan was directing the hunt for Kohinoor McCarthy, the missing third baseman of the Bears, even though it appeared to the two women that he was wasting time. His easy confidence and certainty that McCarthy would be found inspired something of the same spirit in Mrs. Clancy and in Betty Tabor, and they found themselves enjoying the light summer opera to which he had taken them, and later had laughed at his quaint, droll tales of baseball and stories of his own experiences during his long years of travel with the team.

Feehan had found an appreciative audience at last, and it was half after eleven before he broke off suddenly and announced that at midnight he was to get reports of the results of the search and offer his own services in the effort to find the missing player.

"I will telephone you when I reach the office whether anything has been ascertained," he promised, as he left them at their apartments. "After that I will not disturb you until seven o'clock, unless McCarthy is found. We must find him and get him to the station to catch the train at 6.35 or our effort is wasted in so far as baseball is concerned, although, of course, that will not cause us to cease our efforts."

"You'll telephone me the moment you have news?" asked Miss Tabor. "Any time – I shall not sleep much, any news – good – or bad."

Feehan found the office force in the throes of getting out an edition, and he sidled through the hurrying, jostling office force to the city editor.

"Any news?" he asked quietly.

"Hello, Technicalities. Nothing yet. You take the case."

Feehan hurried to his desk, instructed the telephone girls to connect all reporters working on the McCarthy case with his desk, then extracted a mass of papers from various pockets and commenced to study and compile his unending statistics.

The reporters engaged in the search were under instructions to report at once any trace of the missing player and to report once an hour their whereabouts and progress. Every five or ten minutes one reported, and Feehan, laying aside his work, answered the call and suggested new lines of investigations.

Two o'clock came. The office was growing quieter. Weary news gatherers slipped into their coats and departed quietly. Copy readers and editors completed their tasks and went away.

Three o'clock came, and Feehan was busy tabulating the statistics of some player in a far-off league, when the telephone rang. By some inspiration he knew a trail had been found and he reached for the instrument with more haste than he had shown, his seventh sense spurring him on.

"Hello! Yes – that you, Jimmy?"

"I've hit a trail."

The voice was that of little Jimmy Eames, the most tireless and persistent member of the force of news hounds employed by the paper.

"Where?" Feehan was as calm as if only recording a fly out.

"North Ninetieth Street Police Station," said Eames rapidly. "I picked up a clue over on the other side of the city – inside police dope. Man taken there last night in taxi. I'm off for there."

Feehan pocketed his statistics and prepared for action. His voice had ceased to drag. He uttered commands in sharp, quick words. Briefly he detailed to each man as he called on the telephone the nature of Eames's discovery. "Get to North Ninetieth Street Station."

Thirty-five minutes after Eames flashed the first word to the office, Cramer, the star police reporter, announced over the telephone.

"McCarthy is in the black hole at North Ninetieth street. Orders from captain. No one permitted to see him. Not booked. Sergeant in charge don't know what he is accused of."

"Get him out. Report in ten minutes."

"Two hours and a half to get him out and put him on that train," Feehan muttered.

It was twelve minutes before Cramer called again.

"Sergeant says he dares not turn the fellow loose. Don't know he is McCarthy. Says orders are strict to keep him and to keep everyone away from him."

"Is he hurt?"

"Turnkey says he has cut in head and bruised, but all right."

"Pound him – pound the sergeant; make him act. Scare him! Who is the captain?"

"Raferty."

"I'll reach him by 'phone." Feehan hung up the receiver. "Joe," he said to the night man, "raise Minette, the office lawyer. Lives somewhere up that way. His home is only a short distance from Judge Manasse's house. Ask him for a writ of habeas corpus or something."

Feehan was rapidly calling numbers. In fifteen minutes he had aroused Captain Raferty.

"Raferty," said the little man, "sorry to disturb you, but you've got a man in the black hole in your station that we want."

"Can't be done. Orders to hold him."

"Orders from whom?"

"Higher up."

"How high?"

"None of your business."

"Raferty, I'm going to the top," said Feehan quickly. "If that man isn't out by six o'clock, you'll be broken."

"What's all this fuss about some skate?" Raferty was alarmed. "It ain't any of my business. I'm told to hold him and not book him and I do it. What have you got it in for me for?"

"You'd better get to the station and get that man out or you'll have this sheet all over you," threatened Feehan, transformed. "I'm going higher now."

He cut off the spluttering police captain in the midst of a snarling complaint, half whine, half defiance.

Half an hour of hard work brought the indignant superintendent of police to the telephone. He curtly declined to interfere, denied all knowledge of any such prisoner, and hung up the receiver while Feehan was expostulating with him.

The mild mannered, gentle little reporter was rising to the emergency. He wiped his forehead free from the beads of sweat and looked at his watch. It was two minutes to five when the night man reported again.

"Minette's on his way to the station," he said. "He'll try to get Judge Manasse to order the release, and he is carrying ten thousand dollars in securities as a bond."

"Good," said Feehan rapidly. "Give me Gracemont 1328," he called quickly.

"Going after the mayor?" inquired the night man casually. "He'll be sore as a boil. Orders are not to disturb him after midnight."

"I've got to get him," said Feehan. "We can't fall down now after we've located McCarthy."

There was no reply to the call for the mayor's telephone number, and while waiting, Feehan slipped to another telephone and called the hotel at which the ball players lived, asking for the Clancy apartments. Betty Tabor answered the summons.

"We've found him," said Feehan. "He's alive and well."