полная версия

полная версияMore Letters of Charles Darwin — Volume 1

I have read Nos. IV, and V. (156/1. "On our Knowledge of the Causes of the Phenomena of Organic Nature," being six Lectures to Working Men delivered at the Museum of Practical Geology by Prof. Huxley, 1863. These lectures, which were given once a week from November 10th, 1862, onwards, were printed from the notes of Mr. J.A. Mays, a shorthand writer, who asked permission to publish them on his own account; Mr. Huxley stating in a prefatory "Notice" that he had no leisure to revise the lectures.) They are simply perfect. They ought to be largely advertised; but it is very good in me to say so, for I threw down No. IV. with this reflection, "What is the good of writing a thundering big book, when everything is in this green little book, so despicable for its size?" In the name of all that is good and bad, I may as well shut up shop altogether. You put capitally and most simply and clearly the relation of animals and plants to each other at page 122.

Be careful about Fantails: their tail-feathers are fixed in a radiating position, but they can depress and elevate them. I remember in a pigeon-book seeing withering contempt expressed at some naturalist for not knowing this important point! Page 111 (156/2. The reference is to the original little green paper books in which the lectures first appeared; the paging in the bound volume dated 1863 is slightly different. The passage here is, "...If you couple a male and female hybrid...the result is that in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred you will get no offspring at all." Darwin maintains elsewhere that Huxley, from not knowing the botanical evidence, made too much of this point. See "Life and Letters," II., page 384.) seems a little too strong — viz., ninety-nine out of a hundred, unless you except plants.

Page 118: You say the answer to varieties when crossed being at all sterile is "absolutely a negative." (156/3. Huxley, page 112: "Can we find any approximation to this {sterility of hybrids} in the different races known to be produced by selective breeding from a common stock? Up to the present time the answer to that question is absolutely a negative one.") Do you mean to say that Gartner lied, after experiments by the hundred (and he a hostile witness), when he showed that this was the case with Verbascum and with maize (and here you have selected races): does Kolreuter lie when he speaks about the varieties of tobacco? My God, is not the case difficult enough, without its being, as I must think, falsely made more difficult? I believe it is my own fault — my d — d candour: I ought to have made ten times more fuss about these most careful experiments. I did put it stronger in the third edition of the "Origin." If you have a new edition, do consider your second geological section: I do not dispute the truth of your statement; but I maintain that in almost every case the gravel would graduate into the mud; that there would not be a hard, straight line between the mass of gravel and mud; that the gravel, in crawling inland, would be separated from the underlying beds by oblique lines of stratification. A nice idea of the difficulty of Geology your section would give to a working man! Do show your section to Ramsay, and tell him what I say; and if he thinks it a fair section for a beginner I am shut up, and "will for ever hold my tongue." Good-night.

LETTER 157. TO T.H. HUXLEY. Down, {January} 10th {1863}.

You will be weary of notes from me about the little book of yours. It is lucky for me that I expressed, before reading No. VI. (157/1. "Lectures to Working Men," No. VI., is a critical examination of the position of the "Origin of Species" in relation to the complete theory of the "causes of the phenomena of organic nature."), my opinion of its absolute excellence, and of its being well worth wide distribution and worth correction (not that I see where you could improve), if you thought it worth your valuable time. Had I read No. VI., even a rudiment of modesty would, or ought to, have stopped me saying so much. Though I have been well abused, yet I have had so much praise, that I have become a gourmand, both as to capacity and taste; and I really did not think that mortal man could have tickled my palate in the exquisite manner with which you have done the job. So I am an old ass, and nothing more need be said about this. I agree entirely with all your reservations about accepting the doctrine, and you might have gone further with further safety and truth. Of course I do not wholly agree about sterility. I hate beyond all things finding myself in disagreement with any capable judge, when the premises are the same; and yet this will occasionally happen. Thinking over my former letter to you, I fancied (but I now doubt) that I had partly found out the cause of our disagreement, and I attributed it to your naturally thinking most about animals, with which the sterility of the hybrids is much more conspicuous than the lessened fertility of the first cross. Indeed, this could hardly be ascertained with mammals, except by comparing the products of {their} whole life; and, as far as I know, this has only been ascertained in the case of the horse and ass, which do produce fewer offspring in {their} lifetime than in pure breeding. In plants the test of first cross seems as fair as test of sterility of hybrids. And this latter test applies, I will maintain to the death, to the crossing of varieties of Verbascum, and varieties, selected varieties, of Zea. (157/2. See Letter 156.) You will say Go to the Devil and hold your tongue. No, I will not hold my tongue; for I must add that after going, for my present book, all through domestic animals, I have come to the conclusion that there are almost certainly several cases of two or three or more species blended together and now perfectly fertile together. Hence I conclude that there must be something in domestication, — perhaps the less stable conditions, the very cause which induces so much variability, — which eliminates the natural sterility of species when crossed. If so, we can see how unlikely that sterility should arise between domestic races. Now I will hold my tongue. Page 143: ought not "Sanscrit" to be "Aryan"? What a capital number the last "Natural History Review" is! That is a grand paper by Falconer. I cannot say how indignant Owen's conduct about E. Columbi has made me. I believe I hate him more than you do, even perhaps more than good old Falconer does. But I have bubbled over to one or two correspondents on this head, and will say no more. I have sent Lubbock a little review of Bates' paper in "Linn. Transact." (157/3. The unsigned review of Mr. Bates' work on mimetic butterflies appeared in the "Nat. Hist. Review" (1863), page 219.) which L. seems to think will do for your "Review." Do inaugurate a great improvement, and have pages cut, like the Yankees do; I will heap blessings on your head. Do not waste your time in answering this.

LETTER 158. TO JOHN LUBBOCK {LORD AVEBURY}. Down, January 23rd {1863}.

I have no criticism, except one sentence not perfectly smooth. I think your introductory remarks very striking, interesting, and novel. (158/1. "On the Development of Chloeon (Ephemera) dimidiatum, Part I. By John Lubbock. "Trans. Linn. Soc." Volume XXIV., pages 61-78, 1864 {Read January 15th, 1863}.) They interested me the more, because the vaguest thoughts of the same kind had passed through my head; but I had no idea that they could be so well developed, nor did I know of exceptions. Sitaris and Meloe (158/2. Sitaris and Meloe, two genera of coleopterous insects, are referred to by Lubbock (op. cit., pages 63-64) as "perhaps...the most remarkable cases...among the Coleoptera" of curious and complicated metamorphoses.) seem very good. You have put the whole case of metamorphosis in a new light; I dare say what you remark about poverty of fresh-water is very true. (158/3. "We cannot but be struck by the poverty of the fresh-water fauna when compared with that of the ocean" (op. cit., page 64).) I think you might write a memoir on fresh-water productions. I suggest that the key-note is that land-productions are higher and have advantage in general over marine; and consequently land-productions have generally been modified into fresh-water productions, instead of marine productions being directly changed into fresh-water productions, as at first seems more probable, as the chance of immigration is always open from sea to rivers and ponds.

My talk with you did me a deal of good, and I enjoyed it much.

LETTER 159. TO J.D. HOOKER. Down, January 13th {1863}.

I send a very imperfect answer to {your} question, which I have written on foreign paper to save you copying, and you can send when you write to Thomson in Calcutta. Hereafter I shall be able to answer better your question about qualities induced in individuals being inherited; gout in man — loss of wool in sheep (which begins in the first generation and takes two or three to complete); probably obesity (for it is rare with poor); probably obesity and early maturity in short-horn cattle, etc., etc.

LETTER 160. TO A. DE CANDOLLE. Down, January 14th {1863}.

I thank you most sincerely for sending me your Memoir. (160/1. Etude sur l'Espece a l'occasion d'une revision de la Famille des Cupuliferes. "Biblioth. Univ. (Arch. des Sc. Phys. et Nat.)," Novembre 1862.) I have read it with the liveliest interest, as is natural for me; but you have the art of making subjects, which might be dry, run easily. I have been fairly astonished at the amount of individual variability in the oaks. I never saw before the subject in any department of nature worked out so carefully. What labour it must have cost you! You spoke in one letter of advancing years; but I am very sure that no one would have suspected that you felt this. I have been interested with every part; though I am so unfortunate as to differ from most of my contemporaries in thinking that the vast continental extensions (160/2. See Letters 47, 48.) of Forbes, Heer, and others are not only advanced without sufficient evidence, but are opposed to much weighty evidence. You refer to my work in the kindest and most generous spirit. I am fully satisfied at the length in belief to which you go, and not at all surprised at the prudent reservations which you make. I remember well how many years it cost me to go round from old beliefs. It is encouraging to me to observe that everyone who has gone an inch with me, after a period goes a few more inches or even feet. But the great point, as it seems to me, is to give up the immutability of specific forms; as long as they are thought immutable, there can be no real progress in "Epiontology." (160/3. See De Candolle, loc. cit., page 67: he defines "Epiontologie" as the study of the distribution and succession of organised beings from their origin up to the present time. At present Epiontology is divided into geography and palaeontology, "mais cette division trop inegale et a limites bien vagues disparaitra probablement.") It matters very little to any one except myself, whether I am a little more or less wrong on this or that point; in fact, I am sure to be proved wrong in many points. But the subject will have, I am convinced, a grand future. Considering that birds are the most isolated group in the animal kingdom, what a splendid case is this Solenhofen bird-creature with its long tail and fingers to its wings! I have lately been daily and hourly using and quoting your "Geographical Botany" in my book on "Variation under Domestication."

LETTER 161. TO HORACE DOBELL. Down, February 16th {1863}.

Absence from home and consequent idleness are the causes that I have not sooner thanked you for your very kind present of your Lectures. (161/1. "On the Germs and Vestiges of Disease," (London) 1861.) Your reasoning seems quite satisfactory (though the subject is rather beyond my limit of thought and knowledge) on the V.M.F. not being "a given quantity." (161/2. "It has been too common to consider the force exhibited in the operations of life (the V.M.F.) as a given quantity, to which no accessions can be made, but which is apportioned to each living being in quantity sufficient for its necessities, according to some hidden law" (op. cit., page 41.) And I can see that the conditions of life must play a most important part in allowing this quantity to increase, as in the budding of a tree, etc. How far these conditions act on "the forms of organic life" (page 46) I do not see clearly. In fact, no part of my subject has so completely puzzled me as to determine what effect to attribute to (what I vaguely call) the direct action of the conditions of life. I shall before long come to this subject, and must endeavour to come to some conclusion when I have got the mass of collected facts in some sort of order in my mind. My present impression is that I have underrated this action in the "Origin." I have no doubt when I go through your volume I shall find other points of interest and value to me. I have already stumbled on one case (about which I want to consult Mr. Paget) — namely, on the re-growth of supernumerary digits. (161/3. See Letters 178, 270.) You refer to "White on Regeneration, etc., 1785." I have been to the libraries of the Royal and the Linnean Societies, and to the British Museum, where the librarians got out your volume and made a special hunt, and could discover no trace of such a book. Will you grant me the favour of giving me any clue, where I could see the book? Have you it? if so, and the case is given briefly, would you have the great kindness to copy it? I much want to know all particulars. One case has been given me, but with hardly minute enough details, of a supernumerary little finger which has already been twice cut off, and now the operation will soon have to be done for the third time. I am extremely much obliged for the genealogical table; the fact of the two cousins not, as far as yet appears, transmitting the peculiarity is extraordinary, and must be given by me.

LETTER 162. TO C. LYELL. {February 17th, 1863.}

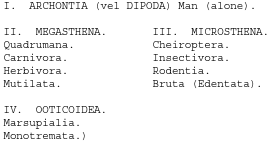

The same post that brought the enclosed brought Dana's pamphlet on the same subject. (162/1. The pamphlet referred to was published in "Silliman's Journal," Volume XXV., 1863, pages 65 and 71, also in the "Annals and Magazine of Natural History," Volume XI., pages 207-14, 1863: "On the Higher Subdivisions in the Classification of Mammals." In this paper Dana maintains the view that "Man's title to a position by himself, separate from the other mammals in classification, appears to be fixed on structural as well as physical grounds" (page 210). His description is as follows: —

The whole seems to me utterly wild. If there had not been the foregone wish to separate men, I can never believe that Dana or any one would have relied on so small a distinction as grown man not using fore-limbs for locomotion, seeing that monkeys use their limbs in all other respects for the same purpose as man. To carry on analogous principles (for they are not identical, in crustacea the cephalic limbs are brought close to mouth) from crustacea to the classification of mammals seems to me madness. Who would dream of making a fundamental distinction in birds, from fore-limbs not being used at all in {some} birds, or used as fins in the penguin, and for flight in other birds?

I get on slowly with your grand work, for I am overwhelmed with odds and ends and letters.

LETTER 163. TO J.D. HOOKER.

(163/1. The following extract refers to Owen's paper in the "Linn. Soc. Journal," June, 1857, in which the classification of the Mammalia by cerebral characters was proposed. In spite of the fact that men and apes are placed in distinct Sub-Classes, Owen speaks (in the foot-note of which Huxley made such telling effect) of the determination of the difference between Homo and Pithecus as the anatomist's difficulty. (See Letter 119.))

July 5th, 1857.

What a capital number of the "Linnean Journal!" Owen's is a grand paper; but I cannot swallow Man making a division as distinct from a chimpanzee as an Ornithorhynchus from a horse; I wonder what a chimpanzee would say to this? (163/2. According to Owen the sub-class Archencephala contains only the genus Homo: the Gyrencephala contains both chimpanzee and horse, the Lyencephala contains Ornithorhynchus.)

LETTER 164. TO T.H. HUXLEY. Down {February?} 26th, 1863.

I have just finished with very great interest "Man's Place." (164/1. "Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature," 1863 (preface dated January 1863).) I never fail to admire the clearness and condensed vigour of your style, as one calls it, but really of your thought. I have no criticisms; nor is it likely that I could have. But I think you could have added some interesting matter on the character or disposition of the young ourangs which have been kept in France and England. I should have thought you might have enlarged a little on the later embryological changes in man and on his rudimentary structure, tail as compared with tail of higher monkeys, intermaxillary bone, false ribs, and I daresay other points, such as muscles of ears, etc., etc. I was very much struck with admiration at the opening pages of Part II. (and oh! what a delicious sneer, as good as a dessert, at page 106) (164/2. Huxley, op. cit., page 106. After saying that "there is but one hypothesis regarding the origin of species of animals in general which has any scientific existence — that propounded by Mr. Darwin," and after a few words on Lamarck, he goes on: "And though I have heard of the announcement of a formula touching 'the ordained continuous becoming of organic forms,' it is obvious that it is the first duty of a hypothesis to be intelligible, and that a qua-qua-versal proposition of this kind, which may be read backwards or forwards, or sideways, with exactly the same amount of significance, does not really exist, though it may seem to do so." The "formula" in question is Owen's.): but my admiration is unbounded at pages 109 to 112. I declare I never in my life read anything grander. Bacon himself could not have charged a few paragraphs with more condensed and cutting sense than you have done. It is truly grand. I regret extremely that you could not, or did not, end your book (not that I mean to say a word against the Geological History) with these pages. With a book, as with a fine day, one likes it to end with a glorious sunset. I congratulate you on its publication; but do not be disappointed if it does not sell largely: parts are highly scientific, and I have often remarked that the best books frequently do not get soon appreciated: certainly large sale is no proof of the highest merit. But I hope it may be widely distributed; and I am rejoiced to see in your note to Miss Rhadamanthus (164/3. This refers to Mr. Darwin's daughter (now Mrs. Litchfield), whom Mr. Huxley used to laugh at for the severity of her criticisms.) that a second thousand is called for of the little book. What a letter that is of Owen's in the "Athenaeum" (164/4. A letter by Owen in the "Athenaeum," February 21st, 1863, replying to strictures on his treatment of the brain question, which had appeared in Lyell's "Antiquity of Man."); how cleverly he will utterly muddle and confound the public. Indeed he quite muddled me, till I read again your "concise statement" (164/5. This refers to a section (pages 113-18) in "Man's Place in Nature," headed "A succinct History of the Controversy respecting the Cerebral Structure of Man and the Apes." Huxley follows the question from Owen's attempt to classify the mammalia by cerebral characters, published by the "Linn. Soc." in 1857, up to his revival of the subject at the Cambridge meeting of the British Association in 1862. It is a tremendous indictment of Owen, and seems to us to conclude not unfittingly with a citation from Huxley's article in the "Medical Times," October 11th, 1862. Huxley here points out that special investigations have been made into the question at issue "during the last two years" by Allen Thomson, Rolleston, Marshall, Flower, Schroeder van der Kolk and Vrolik, and that "all these able and conscientious observers" have testified to the accuracy of his statements, "while not a single anatomist, great or small, has supported Professor Owen." He sums up the case once more, and concludes: "The question has thus become one of personal veracity. For myself I will accept no other issue than this, grave as it is, to the present controversy.") (which is capitally clear), and then I saw that my suspicion was true that he has entirely changed his ground to size of Brain. How candid he shows himself to have taken the slipped Brain! (164/6. Owen in the "Athenaeum," February 21st, 1863, admits that in the brain which he used in illustration of his statements "the cerebral hemispheres had glided forward and apart behind so as to expose a portion of the cerebellum.") I am intensely curious to see whether Lyell will answer. (164/7. Lyell's answer was in the "Athenaeum" March 7th, 1863.) Lyell has been, I fear, rather rash to enter on a subject on which he of course knows nothing by himself. By heavens, Owen will shake himself, when he sees what an antagonist he has made for himself in you. With hearty admiration, Farewell.

I am fearfully disappointed at Lyell's excessive caution (164/8. In the "Antiquity of Man": see "Life and Letters," III., page 8.) in expressing any judgment on Species or {on the} origin of Man.

LETTER 165. TO JOHN SCOTT. Down, March 6th, 1863.

I thank you for your criticisms on the "Origin," and which I have not time to discuss; but I cannot help doubting, from your expression of an "INNATE...selective principle," whether you fully comprehend what is meant by Natural Selection. Certainly when you speak of weaker (i.e. less well adapted) forms crossing with the stronger, you take a widely different view from what I do on the struggle for existence; for such weaker forms could not exist except by the rarest chance. With respect to utility, reflect that 99/100ths part of the structure of each being is due to inheritance of formerly useful structures. Pray read what I have said on "correlation." Orchids ought to show us how ignorant we are of what is useful. No doubt hundreds of cases could be advanced of which no explanation could be offered; but I must stop. Your letter has interested me much. I am very far from strong, and have great fear that I must stop all work for a couple of months for entire rest, and leave home. It will be ruin to all my work.

LETTER 166. TO J.D. HOOKER. Down, April 23rd {1863}.

The more I think of Falconer's letter (166/1. Published in the "Athenaeum" April 4th, 1863, page 459. The writer asserts that Lyell did not make it clear that certain material made use of in the "Antiquity of Man" was supplied by the original work of Mr. Prestwich and himself. (See "Life and Letters," III., page 19.)) the more grieved I am; he and Prestwich (the latter at least must owe much to the "Principles") assume an absurdly unwarrantable position with respect to Lyell. It is too bad to treat an old hero in science thus. I can see from a note from Falconer (about a wonderful fossil Brazilian Mammal, well called Meso- or Typo-therium) that he expects no sympathy from me. He will end, I hope, by being sorry. Lyell lays himself open to a slap by saying that he would come to show his original observations, and then not distinctly doing so; he had better only have laid claim, on this one point of man, to verification and compilation.

Altogether, I much like Lyell's letter. But all this squabbling will greatly sink scientific men. I have seen a sneer already in the "Times."

LETTER 167. TO H.W. BATES. At Rev. C. Langton, Hartfield, Tunbridge Wells, April 30th {1863}.

You will have received before this the note which I addressed to Leicester, after finishing Volume I., and you will have received copies of my little review (167/1. "Nat. Hist. Review," 1863, page 219. A review of Bates' paper on Mimetic Butterflies.) of your paper...I have now finished Volume II., and my opinion remains the same — that you have written a truly admirable work (167/2. "The Naturalist on the Amazons," 1863.), with capital original remarks, first-rate descriptions, and the whole in a style which could not be improved. My family are now reading the book, and admire it extremely; and, as my wife remarks, it has so strong an air of truthfulness. I had a letter from a person the other day, unknown to you, full of praise of the book. I do hope it may get extensively heard of and circulated; but to a certain extent this, I think, always depends on chance.