полная версия

полная версияMore Letters of Charles Darwin — Volume 1

I daresay selection by man would generally work quicker than Natural Selection; but the important distinction between them is, that man can scarcely select except external and visible characters, and secondly, he selects for his own good; whereas under nature, characters of all kinds are selected exclusively for each creature's own good, and are well exercised; but you will find all this in Chapter IV.

Although the hound, greyhound, and bull-dog may possibly have descended from three distinct stocks, I am convinced that their present great amount of difference is mainly due to the same causes which have made the breeds of pigeons so different from each other, though these breeds of pigeons have all descended from one wild stock; so that the Pallasian doctrine I look at as but of quite secondary importance.

In my bigger book I have explained my meaning fully; whether I have in the Abstract I cannot remember.

LETTER 81. TO C. LYELL. {December 5th, 1859.}

I forget whether you take in the "Times;" for the chance of your not doing so, I send the enclosed rich letter. (81/1. See the "Times," December 1st and December 5th, 1859: two letters signed "Senex," dealing with "Works of Art in the Drift.") It is, I am sure, by Fitz-Roy...It is a pity he did not add his theory of the extinction of Mastodon, etc., from the door of the Ark being made too small. (81/2. A postscript to this letter, here omitted, is published in the "Life and Letters," II., page 240.)

LETTER 82. FRANCIS GALTON TO CHARLES DARWIN. 42, Rutland Gate, London, S.W., December 9th, 1859.

Pray let me add a word of congratulation on the completion of your wonderful volume, to those which I am sure you will have received from every side. I have laid it down in the full enjoyment of a feeling that one rarely experiences after boyish days, of having been initiated into an entirely new province of knowledge, which, nevertheless, connects itself with other things in a thousand ways. I hear you are engaged on a second edition. There is a trivial error in page 68, about rhinoceroses (82/1. Down (loc. cit.) says that neither the elephant nor the rhinoceros is destroyed by beasts of prey. Mr. Galton wrote that the wild dogs hunt the young rhinoceros and "exhaust them to death; they pursue them all day long, tearing at their ears, the only part their teeth can fasten on." The reference to the rhinoceros is omitted in later editions of the "Origin."), which I thought I might as well point out, and have taken advantage of the same opportunity to scrawl down half a dozen other notes, which may, or may not, be worthless to you.

(83/1. The three next letters refer to Huxley's lecture on Evolution, given at the Royal Institution on February 10th, 1860, of which the peroration is given in "Life and Letters," II., page 282, together with some letters on the subject.)

LETTER 83. TO T.H. HUXLEY. November 25th {1859}.

I rejoice beyond measure at the lecture. I shall be at home in a fortnight, when I could send you splendid folio coloured drawings of pigeons. Would this be in time? If not, I think I could write to my servants and have them sent to you. If I do NOT hear I shall understand that about fifteen or sixteen days will be in time.

I have had a kind yet slashing letter against me from poor dear old Sedgwick, "who has laughed till his sides ached at my book."

Phillips is cautious, but decidedly, I fear, hostile. Hurrah for the Lecture — it is grand!

LETTER 84. TO T.H. HUXLEY. Down, December 13th {1859}.

I have got fine large drawings (84/1. For Mr. Huxley's R.I. lecture.) of the Pouter, Carrier, and Tumbler; I have only drawings in books of Fantails, Barbs, and Scanderoon Runts. If you had them, you would have a grand display of extremes of diversity. Will they pay at the Royal Institution for copying on a large size drawings of these birds? I could lend skulls of a Carrier and a Tumbler (to show the great difference) for the same purpose, but it would not probably be worth while.

I have been looking at my MS. What you want I believe is about hybridism and breeding. The chapter on hybridism is in a pretty good state — about 150 folio pages with notes and references on the back. My first chapter on breeding is in too bad and imperfect a state to send; but my discussion on pigeons (in about 100 folio pages) is in a pretty good state. I am perfectly convinced that you would never have patience to read such volumes of MS. I speak now in the palace of truth, and pray do you: if you think you would read them I will send them willingly up by my servant, or bring them myself next week. But I have no copy, and I never could possibly replace them; and without you really thought that you would use them, I had rather not risk them. But I repeat I will willingly bring them, if you think you would have the vast patience to use them. Please let me hear on this subject, and whether I shall send the book with small drawings of three other breeds or skulls. I have heard a rumour that Busk is on our side in regard to species. Is this so? It would be very good.

LETTER 85. TO T.H. HUXLEY. Down, December 16th {1859}.

I thank you for your very pleasant and amusing note and invitation to dinner, which I am sorry to say I cannot accept. I shall come up (stomach willing) on Thursday for Phil. Club dinner, and return on Saturday, and I am engaged to my brother for Friday. But I should very much like to call at the Museum on Friday or Saturday morning and see you. Would you let me have one line either here or at 57, Queen Anne Street, to say at what hour you generally come to the Museum, and whether you will be probably there on Friday or Saturday? Even if you are at the Club, it will be a mere chance if we sit near each other.

I will bring up the articles on Thursday afternoon, and leave them under charge of the porter at the Museum. They will consist of large drawings of a Pouter, a Carrier, and rather smaller drawings of some sub-varieties (which breed nearly true) of short-faced Tumblers. Also a small drawing of Scanderoon, a kind of Runt, and a very remarkable breed. Also a book with very moderately good drawings of Fantail and Barb, but I very much doubt whether worth the trouble of enlarging.

Also a box (for Heaven's sake, take care!) with a skull of Carrier and short-faced Tumbler; also lower jaws (largest size) of Runt, middle size of Rock-pigeon, and the broad one of Barb. The form of ramus of jaw differs curiously in these jaws.

Also MS. of hybridism and pigeons, which will just weary you to death. I will call myself for or send a servant for the MS. and bones whenever you have done with them; but do not hurry.

You have hit on the exact plan, which, on the advice of Lyell, Murray, etc., I mean to follow — viz., bring out separate volumes in detail — and I shall begin with domestic productions; but I am determined to try and {work} very slowly, so that, if possible, I may keep in a somewhat better state of health. I had not thought of illustrations; that is capital advice. Farewell, my good and admirable agent for the promulgation of damnable heresies!

LETTER 86. TO L. HORNER. Down, December 23rd {1859}.

I must have the pleasure of thanking you for your extremely kind letter. I am very much pleased that you approve of my book, and that you are going to pay me the extraordinary compliment of reading it twice. I fear that it is tough reading, but it is beyond my powers to make the subject clearer. Lyell would have done it admirably.

You must enjoy being a gentlemen at your ease, and I hear that you have returned with ardour to work at the Geological Society. We hope in the course of the winter to persuade Mrs. Horner and yourself and daughters to pay us a visit. Ilkley did me extraordinary good during the latter part of my stay and during my first week at home; but I have gone back latterly to my bad ways, and fear I shall never be decently well and strong.

P.S. — When any of your party write to Mildenhall I should be much obliged if you would say to Bunbury that I hope he will not forget, whenever he reads my book, his promise to let me know what he thinks about it; for his knowledge is so great and accurate that every one must value his opinions highly. I shall be quite contented if his belief in the immutability of species is at all staggered.

LETTER 87. TO C. LYELL.

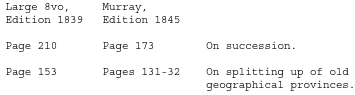

(87/1. In the "Origin of Species" a section of Chapter X. is devoted to "The succession of the same types within the same areas, during the late Tertiary period" (Edition I., page 339). Mr. Darwin wrote as follows: "Mr. Clift many years ago showed that the fossil mammals from the Australian caves were closely allied to the living marsupials of that continent." After citing other instances illustrating the same agreement between fossil and recent types, Mr. Darwin continues: "I was so much impressed with these facts that I strongly insisted, in 1839 and 1845, on this 'law of the succession of types,' on 'this wonderful relationship in the same continent between the dead and the living.' Professor Owen has subsequently extended the same generalisation to the mammals of the Old World.")

Down, {December} 27th {1859}.

Owen wrote to me to ask for the reference to Clift. As my own notes for the late chapters are all in chaos, I bethought me who was the most trustworthy man of all others to look for references, and I answered myself, "Of course Lyell." In the {"Principles of Geology"}, edition of 1833, Volume III., chapter xi., page 144, you will find the reference to Clift in the "Edinburgh New Phil Journal," No. XX., page 394. (87/2. The correct reference to Clift's "Report" on fossil bones from New Holland is "Edinburgh New Phil. Journal," 1831, page 394.) You will also find that you were greatly struck with the fact itself (87/3. This refers to the discovery of recent and fossil species of animals in an Australian cave-breccia. Mr. Clift is quoted as having identified one of the bones, which was much larger than the rest, as that of a hippopotamus.), which I had quite forgotten. I copied the passage, and sent it to Owen. Why I gave in some detail references to my own work is that Owen (not the first occasion with respect to myself and others) quietly ignores my having ever generalised on the subject, and makes a great fuss on more than one occasion at having discovered the law of succession. In fact, this law, with the Galapagos distribution, first turned my mind on the origin of species. My own references are {to the "Naturalist's Voyage"}:

Long before Owen published I had in MS. worked out the succession of types in the Old World (as I remember telling Sedgwick, who of course disbelieved it).

Since receiving your last letter on Hooker, I have read his introduction as far as page xxiv (87/4. "On the Flora of Australia, etc.; being an Introductory Essay to the Flora of Tasmania": London, 1859.), where the Australian flora begins, and this latter part I liked most in the proofs. It is a magnificent essay. I doubt slightly about some assertions, or rather should have liked more facts — as, for instance, in regard to species varying most on the confines of their range. Naturally I doubt a little his remarks about divergence (87/5. "Variation is effected by graduated changes; and the tendency of varieties, both in nature and under cultivation, when further varying, is rather to depart more and more widely from the original type than to revert to it." On the margin Darwin wrote: "Without selection doubtful" (loc. cit., page viii).), and about domestic races being produced under nature without selection. It would take much to persuade me that a Pouter Pigeon, or a Carrier, etc., could have been produced by the mere laws of variation without long continued selection, though each little enlargement of crop and beak are due to variation. I demur greatly to his comparison of the products of sinking and rising islands (87/6. "I venture to anticipate that a study of the vegetation of the islands with reference to the peculiarities of the generic types on the one hand, and of the geological conditions (whether as rising or sinking) on the other, may, in the present state of our knowledge, advance other subjects of distribution and variation considerably" (loc. cit., page xv).); in the Indian Ocean he compares exclusively many rising volcanic and sinking coral islands. The latter have a most peculiar soil, and are excessively small in area, and are tenanted by very few species; moreover, such low coral islands have probably been often, during their subsidence, utterly submerged, and restocked by plants from other islands. In the Pacific Ocean the floras of all the best cases are unknown. The comparison ought to have been exclusively between rising and fringed volcanic islands, and sinking and encircled volcanic islands. I have read Naudin (87/7. Naudin, "Revue Horticole," 1852?.), and Hooker agrees that he does not even touch on my views.

LETTER 88. J.D. HOOKER TO CHARLES DARWIN. {1859 or 1860.}

I have had another talk with Bentham, who is greatly agitated by your book: evidently the stern, keen intellect is aroused, and he finds that it is too late to halt between two opinions. How it will go we shall see. I am intensely interested in what we shall come to, and never broach the subject to him. I finished the geological evidence chapters yesterday; they are very fine and very striking, but I cannot see they are such forcible objections as you still hold them to be. I would say that you still in your secret soul underrate the imperfection of the Geological Record, though no language can be stronger or arguments fairer and sounder against it. Of course I am influenced by Botany, and the conviction that we have not in a fossilised condition a fraction of the plants that have existed, and that not a fraction of those we have are recognisable specifically. I never saw so clearly put the fact that it is not intermediates between existing species we want, but between these and the unknown tertium quid.

You certainly make a hobby of Natural Selection, and probably ride it too hard; that is a necessity of your case. If the improvement of the creation-by-variation doctrine is conceivable, it will be by unburthening your theory of Natural Selection, which at first sight seems overstrained — i.e., to account for too much. I think, too, that some of your difficulties which you override by Natural Selection may give way before other explanations. But, oh Lord! how little we do know and have known to be so advanced in knowledge by one theory. If we thought ourselves knowing dogs before you revealed Natural Selection, what d — d ignorant ones we must surely be now we do know that law.

I hear you may be at the Club on Thursday. I hope so. Huxley will not be there, so do not come on that ground.

LETTER 89. TO T.H. HUXLEY. January 1st {1860}.

I write one line merely to thank you for your pleasant note, and to say that I will keep your secret. I will shake my head as mysteriously as Lord Burleigh. Several persons have asked me who wrote that "most remarkable article" in the "Times." (89/1. The "Times," December 26th, 1859, page 8. The opening paragraphs were by one of the staff of the "Times." See "Life and Letters," II., page 255, for Mr. Huxley's interesting account of his share in the matter.) As a cat may look at a king, so I have said that I strongly suspected you. X was so sharp that the first sentence revealed the authorship. The Z's (God save the mark) thought it was Owen's! You may rely on it that it has made a deep impression, and I am heartily glad that the subject and I owe you this further obligation. But for God's sake, take care of your health; remember that the brain takes years to rest, whilst the muscles take only hours. There is poor Dana, to whom I used to preach by letter, writes to me that my prophecies are come true: he is in Florence quite done up, can read nothing and write nothing, and cannot talk for half an hour. I noticed the "naughty sentence" (89/2. Mr. Huxley, after speaking of the rudimental teeth of the whale, of rudimental jaws in insects which never bite, and rudimental eyes in blind animals, goes on: "And we would remind those who, ignorant of the facts, must be moved by authority, that no one has asserted the incompetence of the doctrine of final causes, in its application to physiology and anatomy, more strongly than our own eminent anatomist, Professor Owen, who, speaking of such cases, says ("On the Nature of Limbs," pages 39, 40), 'I think it will be obvious that the principle of final adaptations fails to satisfy all the conditions of the problem.'" — "The Times," December 26th, 1859.) about Owen, though my wife saw its bearing first. Farewell you best and worst of men!

That sentence about the bird and the fish dinners charmed us. Lyell wrote to me — style like yours.

Have you seen the slashing article of December 26th in the "Daily News," against my stealing from my "master," the author of the "Vestiges?"

LETTER 90. TO J.L.A. DE QUATREFAGES. {Undated}

How I should like to know whether Milne Edwards has read the copy which I sent him, and whether he thinks I have made a pretty good case on our side of the question. There is no naturalist in the world for whose opinion I have so profound a respect. Of course I am not so silly as to expect to change his opinion.

LETTER 91. TO C. LYELL.

(91/1. The date of this letter is doubtful; but as it evidently refers to the 2nd edition of the "Origin," which appeared on January 7th, 1860, we believe that December 9th, 1859, is right. The letter of Sedgwick's is doubtless that given in the "Life and Letters," II., page 247; it is there dated December 24th, 1859, but from other evidence it was probably written on November 24th)

{December?} 9th {1859}.

I send Sedgwick's letter; it is terribly muddled, and really the first page seems almost childish.

I am sadly over-worked, so will not write to you. I have worked in a number of your invaluable corrections — indeed, all as far as time permits. I infer from a letter from Huxley that Ramsay (91/2. See a letter to Huxley, November 27th, 1859, "Life and Letters," II., page 282.) is a convert, and I am extremely glad to get pure geologists, as they will be very few. Many thanks for your very pleasant note. What pleasure you have given me. I believe I should have been miserable had it not been for you and a few others, for I hear threatening of attacks which I daresay will be severe enough. But I am sure that I can now bear them.

LETTER 92. TO T.H. HUXLEY.

(92/1. The point here discussed is one to which Mr. Huxley attached great, in our opinion too great, importance.)

Down, January 11th {1860?}.

I fully agree that the difficulty is great, and might be made much of by a mere advocate. Will you oblige me by reading again slowly from pages 267 to 272. (92/2. The reference is to the "Origin," Edition I.: the section on "The Fertility of Varieties when crossed, and of their Mongrel Offspring" occupies pages 267-72.) I may add to what is there said, that it seems to me quite hopeless to attempt to explain why varieties are not sterile, until we know the precise cause of sterility in species.

Reflect for a moment on how small and on what very peculiar causes the unequal reciprocity of fertility in the same two species must depend. Reflect on the curious case of species more fertile with foreign pollen than their own. Reflect on many cases which could be given, and shall be given in my larger book (independently of hybridity) of very slight changes of conditions causing one species to be quite sterile and not affecting a closely allied species. How profoundly ignorant we are on the intimate relation between conditions of life and impaired fertility in pure species!

The only point which I might add to my short discussion on this subject, is that I think it probable that the want of adaptation to uniform conditions of life in our domestic varieties has played an important part in preventing their acquiring sterility when crossed. For the want of uniformity, and changes in the conditions of life, seem the only cause of the elimination of sterility (when crossed) under domestication. (92/3. The meaning which we attach to this obscure sentence is as follows: Species in a state of nature are closely adapted to definite conditions of life, so that the sexual constitution of species A is attuned, as it were, to a condition different from that to which B is attuned, and this leads to sterility. But domestic varieties are not strictly adapted by Natural Selection to definite conditions, and thus have less specialised sexual constitutions.) This elimination, though admitted by many authors, rests on very slight evidence, yet I think is very probably true, as may be inferred from the case of dogs. Under nature it seems improbable that the differences in the reproductive constitution, on which the sterility of any two species when crossed depends, can be acquired directly by Natural Selection; for it is of no advantage to the species. Such differences in reproductive constitution must stand in correlation with some other differences; but how impossible to conjecture what these are! Reflect on the case of the variations of Verbascum, which differ in no other respect whatever besides the fluctuating element of the colour of the flower, and yet it is impossible to resist Gartner's evidence, that this difference in the colour does affect the mutual fertility of the varieties.

The whole case seems to me far too mysterious to rest (92/4. The word "rest" seems to be used in place of "to serve as a foundation for.") a valid attack on the theory of modification of species, though, as you say, it offers excellent ground for a mere advocate.

I am surprised, considering how ignorant we are on very many points, {that} more weak parts in my book have not as yet been pointed out to me. No doubt many will be. H.C. Watson founds his objection in MS. on there being no limit to infinite diversification of species: I have answered this, I think, satisfactorily, and have sent attack and answer to Lyell and Hooker. If this seems to you a good objection, I would send papers to you. Andrew Murray "disposes of" the whole theory by an ingenious difficulty from the distribution of blind cave insects (92/5. See "Life and Letters, Volume II., page 265. The reference here is to Murray's address before the Botanical Society, Edinburgh. Mr. Darwin seems to have read Murray's views only in a separate copy reprinted from the "Proc. R. Soc. Edin." There is some confusion about the date of the paper; the separate copy is dated January 16th, while in the volume of the "Proc. R. Soc." it is February 20th. In the "Life and Letters," II., page 261 it is erroneously stated that these are two different papers.); but it can, I think, be fairly answered.

LETTER 93. TO T.H. HUXLEY. Down, {February} 2nd {1860}.

I have had this morning a letter from old Bronn (93/1. See "Life and Letters, II., page 277.) (who, to my astonishment, seems slightly staggered by Natural Selection), and he says a publisher in Stuttgart is willing to publish a translation, and that he, Bronn, will to a certain extent superintend. Have you written to Kolliker? if not, perhaps I had better close with this proposal — what do you think? If you have written, I must wait, and in this case will you kindly let me hear as soon as you hear from Kolliker?

My poor dear friend, you will curse the day when you took up the "general agency" line; but really after this I will not give you any more trouble.

Do not forget the three tickets for us for your lecture, and the ticket for Baily, the poulterer.

Old Bronn has published in the "Year-book for Mineralogy" a notice of the "Origin" (93/2. "Neues Jahrb. fur Min." 1860, page 112.); and says he has himself published elsewhere a foreboding of the theory!

LETTER 94. TO J.D. HOOKER. Down, February 14th {1860}.

I succeeded in persuading myself for twenty-four hours that Huxley's lecture was a success. (94/1. At the Royal Institution. See "Life and Letters," II., page 282.) Parts were eloquent and good, and all very bold; and I heard strangers say, "What a good lecture!" I told Huxley so; but I demurred much to the time wasted in introductory remarks, especially to his making it appear that sterility was a clear and manifest distinction of species, and to his not having even alluded to the more important parts of the subject. He said that he had much more written out, but time failed. After conversation with others and more reflection, I must confess that as an exposition of the doctrine the lecture seems to me an entire failure. I thank God I did not think so when I saw Huxley; for he spoke so kindly and magnificently of me, that I could hardly have endured to say what I now think. He gave no just idea of Natural Selection. I have always looked at the doctrine of Natural Selection as an hypothesis, which, if it explained several large classes of facts, would deserve to be ranked as a theory deserving acceptance; and this, of course, is my own opinion. But, as Huxley has never alluded to my explanation of classification, morphology, embryology, etc., I thought he was thoroughly dissatisfied with all this part of my book. But to my joy I find it is not so, and that he agrees with my manner of looking at the subject; only that he rates higher than I do the necessity of Natural Selection being shown to be a vera causa always in action. He tells me he is writing a long review in the "Westminster." It was really provoking how he wasted time over the idea of a species as exemplified in the horse, and over Sir J. Hall's old experiment on marble. Murchison was very civil to me over my book after the lecture, in which he was disappointed. I have quite made up my mind to a savage onslaught; but with Lyell, you, and Huxley, I feel confident we are right, and in the long run shall prevail. I do not think Asa Gray has quite done you justice in the beginning of the review of me. (94/2. "Review of Darwin's Theory on the Origin of Species by means of Natural Selection," by "A.G." ("Amer. Jour. Sci." Volume XXIX., page 153, 1860). In a letter to Asa Gray on February 18th, 1860, Darwin writes: "Your review seems to me admirable; by far the best which I have read." ("Life and Letters," II., 1887, page 286.) The review seemed to me very good, but I read it very hastily.