полная версия

полная версияMore Letters of Charles Darwin — Volume 2

Of nearly allied plants sleeping very differently I can give you some more instances. In the genus Olyra (at least, in the one species observed by me) the leaves bend down vertically at night; now, in Endlicher's "Genera plantarum" this genus immediately precedes Strephium, the leaves of which you saw rising vertically.

In one of two species of Phyllanthus, growing as weeds near my house, the leaves of the erect branches bend upwards at night, while in the second species, with horizontal branches, they sleep like those of Phyllanthus Niruri or of Cassia. In this second species the tips of the branches also are curled downwards at night, by which movement the youngest leaves are yet better protected. From their vertical nyctitropic position the leaves of this Phyllanthus might return to horizontality, traversing 90 deg, in two ways, either to their own or to the opposite side of the branch; on the latter way no rotation would be required, while on the former each leaf must rotate on its own axis in order that its upper surface may be turned upwards. Thus the way to the wrong side appears to be even less troublesome. And indeed, in some rare cases I have seen three, four or even almost all the leaves of one side of a branch horizontally expanded on the opposite side, with their upper surfaces closely appressed to the lower surfaces of the leaves of that side.

This Phyllanthus agrees with Cassia not only in its manner of sleeping, but also by its leaves being paraheliotropic. (687/2. Paraheliotropism is the movement by which some leaves temporarily direct their edges to the source of light. See "Movements of Plants," page 445.) Like those of some Cassiae its leaves take an almost perfectly vertical position, when at noon, on a summer day, the sun is nearly in the zenith; but I doubt whether this paraheliotropism will be observable in England. To-day, though continuing to be fully exposed to the sun, at 3 p.m. the leaves had already returned to a nearly horizontal position. As soon as there are ripe seeds I will send you some; of our other species of Phyllanthus I enclose a few seeds in this letter.

In several species of Hedychium the lateral halves of the leaves when exposed to bright sunshine, bend downwards so that the lateral margins meet. It is curious that a hybrid Hedychium in my garden shows scarcely any trace of this paraheliotropism, while both the parent species are very paraheliotropic.

Might not the inequality of the cotyledons of Citrus and of Pachira be attributed to the pressure, which the several embryos enclosed in the same seed exert upon each other? I do not know Pachira aquatica, but {in} a species, of which I have a tree in my garden, all the seeds are polyembryonic, and so were almost all the seeds of Citrus which I examined. With Coffea arabica also seeds including two embryos are not very rare; but I have not yet observed whether in this case the cotyledons be inequal.

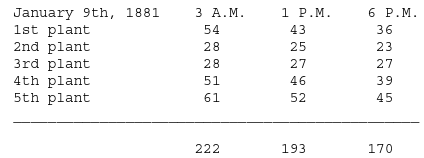

I repeated to-day Duval-Jouve's measurements on Bryophyllum calycinum (687/3. "Power of Movement in Plants," page 237. F. Muller's measurements show, however, that there is a tendency in the leaves to be more highly inclined at night than in the middle of the day, and so far they agree with Duval-Jouve's results.); but mine did not agree with his; they are as follows: —

Distances in mm. between the tips of the upper pair of leaves.

LETTER 688. TO F. MULLER. Down, February 23rd, 1881.

Your letter has interested me greatly, as have so many during many past years. I thought that you would not object to my publishing in "Nature" (688/1. "Nature," March 3rd, 1881, page 409.) some of the more striking facts about the movements of plants, with a few remarks added to show the bearing of the facts. The case of the Phyllanthus (688/2. See Letter 687.), which turns up its leaves on the wrong side, is most extraordinary and ought to be further investigated. Do the leaflets sleep on the following night in the usual manner? Do the same leaflets on successive nights move in the same strange manner? I was particularly glad to hear of the strongly marked cases of paraheliotropism. I shall look out with much interest for the publication about the figs. (688/3. F. Muller published on Caprification in "Kosmos," 1882.) The creatures which you sketch are marvellous, and I should not have guessed that they were hymenoptera. Thirty or forty years ago I read all that I could find about caprification, and was utterly puzzled. I suggested to Dr. Cruger in Trinidad to investigate the wild figs, in relation to their cross-fertilisation, and just before he died he wrote that he had arrived at some very curious results, but he never published, as I believe, on the subject.

I am extremely glad that the inundation did not so greatly injure your scientific property, though it would have been a real pleasure to me to have been allowed to have replaced your scientific apparatus. (688/4. See Letter 687.) I do not believe that there is any one in the world who admires your zeal in science and wonderful powers of observation more than I do. I venture to say this, as I feel myself a very old man, who probably will not last much longer.

P.S. — With respect to Phyllanthus, I think that it would be a good experiment to cut off most of the leaflets on one side of the petiole, as soon as they are asleep and vertically dependent; when the pressure is thus removed, the opposite leaflets will perhaps bend beyond their vertically dependent position; if not, the main petiole might be a little twisted so that the upper surfaces of the dependent and now unprotected leaflets should face obliquely the sky when the morning comes. In this case diaheliotropism would perhaps conquer the ordinary movements of the leaves when they awake, and {assume} their diurnal horizontal position. As the leaflets are alternate, and as the upper surface will be somewhat exposed to the dawning light, it is perhaps diaheliotropism which explains your extraordinary case.

LETTER 689. TO F. MULLER. Down, April 12th, 1881.

I have delayed answering your last letter of February 25th, as I was just sending to the printers the MS. of a very little book on the habits of earthworms, of which I will of course send you a copy when published. I have been very much interested by your new facts on paraheliotropism, as I think that they justify my giving a name to this kind of movement, about which I long doubted. I have this morning drawn up an account of your observations, which I will send in a few days to "Nature." (689/1. "Nature," 1881, page 603. Curious facts are given on the movements of Cassia, Phyllanthus, sp., Desmodium sp. Cassia takes up a sunlight position unlike its own characteristic night-position, but resembling rather that of Haematoxylon (see "Power of Movement," figure 153, page 369). One species of Phyllanthus takes up in sunshine the nyctitropic attitude of another species. And the same sort of relation occurs in the genus Bauhinia.) I have thought that you would not object to my giving precedence to paraheliotropism, which has been so little noticed. I will send you a copy of "Nature" when published. I am glad that I was not in too great a hurry in publishing about Lagerstroemia. (689/2. Lagerstraemia was doubtfully placed among the heterostyled plants ("Forms of Flowers," page 167). F. Muller's observations showed that a totally different interpretation of the two sizes of stamen is possible. Namely, that one set serves merely to attract pollen-collecting bees, who in the act of visiting the flowers transfer the pollen of the longer stamens to other flowers. A case of this sort in Heeria, a Melastomad, was described by Muller ("Nature," August 4th, 1881, page 308), and the view was applied to the cases of Lagerstroemia and Heteranthera at a later date ("Nature," 1883, page 364). See Letters 620-30.) I have procured some plants of Melastomaceae, but I fear that they will not flower for two years, and I may be in my grave before I can repeat my trials. As far as I can imperfectly judge from my observations, the difference in colour of the anthers in this family depends on one set of anthers being partially aborted. I wrote to Kew to get plants with differently coloured anthers, but I learnt very little, as describers of dried plants do not attend to such points. I have, however, sowed seeds of two kinds, suggested to me as probable. I have, therefore, been extremely glad to receive the seeds of Heteranthera reniformis. As far as I can make out it is an aquatic plant; and whether I shall succeed in getting it to flower is doubtful. Will you be so kind as to send me a postcard telling me in what kind of station it grows. In the course of next autumn or winter, I think that I shall put together my notes (if they seem worth publishing) on the use or meaning of "bloom" (689/3. See Letters 736-40.), or the waxy secretion which makes some leaves glaucous. I think that I told you that my experiments had led me to suspect that the movement of the leaves of Mimosa, Desmodium and Cassia, when shaken and syringed, was to shoot off the drops of water. If you are caught in heavy rain, I should be very much obliged if you would keep this notion in your mind, and look to the position of such leaves. You have such wonderful powers of observation that your opinion would be more valued by me than that of any other man. I have among my notes one letter from you on the subject, but I forget its purport. I hope, also, that you may be led to follow up your very ingenious and novel view on the two-coloured anthers or pollen, and observe which kind is most gathered by bees.

LETTER 690. TO F. MULLER. {Patterdale}, June 21st, 1881.

I should be much obliged if you could without much trouble send me seeds of any heterostyled herbaceous plants (i.e. a species which would flower soon), as it would be easy work for me to raise some illegitimate seedlings to test their degree of infertility. The plant ought not to have very small flowers. I hope that you received the copies of "Nature," with extracts from your interesting letters (690/1. "Nature," March 3rd, 1881, Volume XXIII., page 409, contains a letter from C. Darwin on "Movements of Plants," with extracts from Fritz Muller's letter. Another letter, "On the Movements of Leaves," was published in "Nature," April 28th, 1881, page 603, with notes on leaf-movements sent to Darwin by Muller.), and I was glad to see a notice in "Kosmos" on Phyllanthus. (690/2. "Verirrte Blatter," by Fritz Muller ("Kosmos," Volume V., page 141, 1881). In this article an account is given of a species of Phyllanthus, a weed in Muller's garden. See Letter 687.) I am writing this note away from my home, but before I left I had the satisfaction of seeing Phyllanthus sleeping. Some of the seeds which you so kindly sent me would not germinate, or had not then germinated. I received a letter yesterday from Dr. Breitenbach, and he tells me that you lost many of your books in the desolating flood from which you suffered. Forgive me, but why should you not order, through your brother Hermann, books, etc., to the amount of 100 pounds, and I would send a cheque to him as soon as I heard the exact amount? This would be no inconvenience to me; on the contrary, it would be an honour and lasting pleasure to me to have aided you in your invaluable scientific work to this small and trifling extent. (690/3. See Letter 687, also "Life and Letters," III., page 242.)

LETTER 691. TO F. MULLER.

(691/1. The following extract from a letter to F. Muller shows what was the nature of Darwin's interest in the effect of carbonate of ammonia on roots, etc. He was, we think, wrong in adhering to the belief that the movements of aggregated masses are of an amoeboid nature. The masses change shape, just as clouds do under the moulding action of the wind. In the plant cell the moulding agent is the flowing protoplasm, but the masses themselves are passive.)

September 10th, 1881.

Perhaps you may remember that I described in "Insectivorous Plants" a really curious phenomenon, which I called the aggregation of the protoplasm in the cells of the tentacles. None of the great German botanists will admit that the moving masses are composed of protoplasm, though it is astonishing to me that any one could watch the movement and doubt its nature. But these doubts have led me to observe analogous facts, and I hope to succeed in proving my case.

LETTER 692. TO F. MULLER. Down, November 13th, 1881.

I received a few days ago a small box (registered) containing dried flower-heads with brown seeds somewhat sculptured on the sides. There was no name, and I should be much obliged if some time you would tell me what these seeds are. I have planted them.

I sent you some time ago my little book on earthworms, which, though of no importance, has been largely read in England. I have little or nothing to tell you about myself. I have for a couple of months been observing the effects of carbonate of ammonia on chlorophyll and on the roots of certain plants (692/1. Published under the title "The Action of Carbonate of Ammonia on the Roots of Certain Plants and on Chlorophyll Bodies," "Linn. Soc. Journ." XIX., 1882, pages 239-61, 262-84.), but the subject is too difficult for me, and I cannot understand the meaning of some strange facts which I have observed. The mere recording new facts is but dull work.

Professor Wiesner has published a book (692/2. See Letter 763.), giving a different explanation to almost every fact which I have given in my "Power of Movement in Plants." I am glad to say that he admits that almost all my statements are true. I am convinced that many of his interpretations of the facts are wrong, and I am glad to hear that Professor Pfeffer is of the same opinion; but I believe that he is right and I wrong on some points. I have not the courage to retry all my experiments, but I hope to get my son Francis to try some fresh ones to test Wiesner's explanations. But I do not know why I have troubled you with all this.

LETTER 693. TO F. MULLER. {4, Bryanston Street}, December 19th, 1881.

I hope that you may find time to go on with your experiments on such plants as Lagerstroemia, mentioned in your letter of October 29th, for I believe you will arrive at new and curious results, more especially if you can raise two sets of seedlings from the two kinds of pollen.

Many thanks for the facts about the effect of rain and mud in relation to the waxy secretion. I have observed many instances of the lower side being protected better than the upper side, in the case, as I believe, of bushes and trees, so that the advantage in low-growing plants is probably only an incidental one. (693/1. The meaning is here obscure: it appears to us that the significance of bloom on the lower surface of the leaves of both trees and herbs depends on the frequency with which all or a majority of the stomata are on the lower surface — where they are better protected from wet (even without the help of bloom) than on the exposed upper surface. On the correlation between bloom and stomata, see Francis Darwin "Linn. Soc. Journ." XXII., page 99.) As I am writing away from my home, I have been unwilling to try more than one leaf of the Passiflora, and this came out of the water quite dry on the lower surface and quite wet on the upper. I have not yet begun to put my notes together on this subject, and do not at all know whether I shall be able to make much of it. The oddest little fact which I have observed is that with Trifolium resupinatum, one half of the leaf (I think the right-hand side, when the leaf is viewed from the apex) is protected by waxy secretion, and not the other half (693/2. In the above passage "leaf" should be "leaflet": for a figure of Trifolium resupinatum see Letter 740.); so that when the leaf is dipped into water, exactly half the leaf comes out dry and half wet. What the meaning of this can be I cannot even conjecture. I read last night your very interesting article in "Kosmos" on Crotalaria, and so was very glad to see the dried leaves sent by you: it seems to me a very curious case. I rather doubt whether it will apply to Lupinus, for, unless my memory deceives me, all the leaves of the same plant sometimes behaved in the same manner; but I will try and get some of the same seeds of the Lupinus, and sow them in the spring. Old age, however, is telling on me, and it troubles me to have more than one subject at a time on hand.

(693/3. In a letter to F. Muller (September 10, 1881) occurs a sentence which may appropriately close this series: "I often feel rather ashamed of myself for asking for so many things from you, and for taking up so much of your valuable time, but I can assure you that I feel grateful.")

2. XI.III. MISCELLANEOUS, 1868-1881.

LETTER 694. TO G. BENTHAM. Down, April 22nd, 1868.

I have been extremely much pleased by your letter, and I take it as a very great compliment that you should have written to me at such length...I am not at all surprised that you cannot digest pangenesis: it is enough to give any one an indigestion; but to my mind the idea has been an immense relief, as I could not endure to keep so many large classes of facts all floating loose in my mind without some thread of connection to tie them together in a tangible method.

With respect to the men who have recently written on the crossing of plants, I can at present remember only Hildebrand, Fritz Muller, Delpino, and G. Henslow; but I think there are others. I feel sure that Hildebrand is a very good observer, for I have read all his papers, and during the last twenty years I have made unpublished observations on many of the plants which he describes. {Most of the criticisms which I sometimes meet with in French works against the frequency of crossing I am certain are the result of mere ignorance. I have never hitherto found the rule to fail that when an author describes the structure of a flower as specially adapted for self-fertilisation, it is really adapted for crossing. The Fumariaceae offer a good instance of this, and Treviranus threw this order in my teeth; but in Corydalis Hildebrand shows how utterly false the idea of self-fertilisation is. This author's paper on Salvia (694/1. Hildebrand, "Pringsheim's Jahrbucher," IV.) is really worth reading, and I have observed some species, and know that he is accurate}. (694/2. The passage within {} was published in the "Life and Letters," III., page 279.) Judging from a long review in the "Bot. Zeitung", and from what I know of some the plants, I believe Delpino's article especially on the Apocynaea, is excellent; but I cannot read Italian. (694/3. Hildebrand's paper in the "Bot. Zeitung," 1867, refers to Delpino's work on the Asclepiads, Apocyneae and other Orders.) Perhaps you would like just to glance at such pamphlets as I can lay my hands on, and therefore I will send them, as if you do not care to see them you can return them at once; and this will cause you less trouble than writing to say you do not care to see them. With respect to Primula, and one point about which I feel positive is that the Bardfield and common oxlips are fundamentally distinct plants, and that the common oxlip is a sterile hybrid. (694/4. For a general account of the Bardfield oxlip (Primula elatior) see Miller Christy, "Linn. Soc. Journ." Volume XXXIII., page 172, 1897.) I have never heard of the common oxlip being found in great abundance anywhere, and some amount of difference in number might depend on so small a circumstance as the presence of some moth which habitually sucked the primrose and cowslip. To return to the subject of crossing: I am experimenting on a very large scale on the difference in power and growth between plants raised from self-fertilised and crossed seeds, and it is no exaggeration to say that the difference in growth and vigour is sometimes truly wonderful. Lyell, Huxley, and Hooker have seen some of my plants, and been astonished; and I should much like to show them to you. I always supposed until lately that no evil effects would be visible until after several generations of self-fertilisation, but now I see that one generation sometimes suffices, and the existence of dimorphic plants and all the wonderful contrivances of orchids are quite intelligible to me.

LETTER 695. TO T.H. FARRER (Lord Farrer). Down, June 5th, 1868.

I must write a line to cry peccavi. I have seen the action in Ophrys exactly as you describe, and am thoroughly ashamed of my inaccuracy. (695/1. See "Fertilisation of Orchids," Edition II., page 46, where Lord Farrer's observations on the movement of the pollinia in Ophrys muscifera are given.) I find that the pollinia do not move if kept in a very damp atmosphere under a glass; so that it is just possible, though very improbable, that I may have observed them during a very damp day.

I am not much surprised that I overlooked the movement in Habenaria, as it takes so long. (695/2. This refers to Peristylus viridis, sometimes known as Habenaria viridis. Lord Farrer's observations are given in "Fertilisation of Orchids," Edition II., page 63.)

I am glad you have seen Listera; it requires to be seen to believe in the co-ordination in the position of the parts, the irritability, and the chemical nature of the viscid fluid. This reminds me that I carefully described to Huxley the shooting out of the pollinia in Catasetum, and received for an answer, "Do you really think that I can believe all that!" (695/3. See Letter 665.)

LETTER 696. TO J.D. HOOKER. Down, December 2nd, 1868.

It is a splendid scheme, and if you make only a beginning on a "Flora," which shall serve as an index to all papers on curious points in the life-history of plants, you will do an inestimable good service. Quite recently I was asked by a man how he could find out what was known on various biological points in our plants, and I answered that I knew of no such book, and that he might ask half a dozen botanists before one would chance to remember what had been published on this or that point. Not long ago another man, who had been experimenting on the quasi-bulbs on the leaves of Cardamine, wrote to me to complain that he could not find out what was known on the subject. It is almost certain that some early or even advanced students, if they found in their "Flora" a line or two on various curious points, with references for further investigation, would be led to make further observations. For instance, a reference to the viscid threads emitted by the seeds of Compositae, to the apparatus (if it has been described) by which Oxalis spurts out its seeds, to the sensitiveness of the young leaves of Oxalis acetosella with reference to O. sensitiva. Under Lathyrus nissolia it would {be} better to refer to my hypothetical explanation of the grass-like leaves than to nothing. (696/1. No doubt the view given in "Climbing Plants," page 201, that L. nissolia has been evolved from a form like L. aphaca.) Under a twining plant you might say that the upper part of the shoot steadily revolves with or against the sun, and so, when it strikes against any object it turns to the right or left, as the case may be. If, again, references were given to the parasitism of Euphrasia, etc., how likely it would be that some young man would go on with the investigation; and so with endless other facts. I am quite enthusiastic about your idea; it is a grand idea to make a "Flora" a guide for knowledge already acquired and to be acquired. I have amused myself by speculating what an enormous number of subjects ought to be introduced into a Eutopian (696/2. A mis-spelling of Utopian.) Flora, on the quickness of the germination of the seeds, on their means of dispersal; on the fertilisation of the flower, and on a score of other points, about almost all of which we are profoundly ignorant. I am glad to read what you say about Bentham, for my inner consciousness tells me that he has run too many forms together. Should you care to see an elaborate German pamphlet by Hermann Muller on the gradation and distinction of the forms of Epipactis and of Platanthera? (696/3. "Verhand. d. Nat. Ver. f. Pr. Rh. u. Wesfal." Jahrg. XXV.: see "Fertilisation of Orchids," Edition II., pages 74, 102.) It may be absurd in me to suggest, but I think you would find curious facts and references in Lecoq's enormous book (696/4. "Geographie Botanique," 9 volumes, 1854-58.), in Vaucher's four volumes (696/5. "Plantes d'Europe," 4 volumes, 1841.), in Hildebrand's "Geschlechter Vertheilung" (696/6 "Geschlechter Vertheilung bei den Pflanzen," 1 volume, Leipzig, 1867.), and perhaps in Fournier's "De la Fecondation." (696/7. "De la Fecondation dans les Phanerogames," par Eugene Fournier: thesis published in Paris in 1863. The facts noted in Darwin's copy are the explosive stamens of Parietaria, the submerged flowers of Alisma containing air, the manner of fertilisation of Lopezia, etc.) I wish you all success in your gigantic undertaking; but what a pity you did not think of it ten years ago, so as to have accumulated references on all sorts of subjects. Depend upon it, you will have started a new era in the floras of various countries. I can well believe that Mrs. Hooker will be of the greatest possible use to you in lightening your labours and arranging your materials.