полная версия

полная версияLife and Letters of Charles Darwin — Volume 1

Urge the use of the dredge in the Tropics; how little or nothing we know of the limit of life downward in the hot seas?

My present work leads me to perceive how much the domestic animals have been neglected in out of the way countries.

The Revillagigedo Island off Mexico, I believe, has never been trodden by foot of naturalist.

If the expedition sticks to such places as Rio, Cape of Good Hope, Ceylon and Australia, etc., it will not do much.

Ever yours most truly, C. DARWIN.

[The following passage occurs in a letter to Mr. Fox, February 22, 1857, and has reference to the book on Evolution on which he was still at work. The remainder of the letter is made up in details of no interest:

"I am got most deeply interested in my subject; though I wish I could set less value on the bauble fame, either present or posthumous, than I do, but not I think, to any extreme degree: yet, if I know myself, I would work just as hard, though with less gusto, if I knew that my book would be published for ever anonymously."]

CHARLES DARWIN TO A.R. WALLACE. Moor Park, May 1st, 1857.

My dear Sir,

I am much obliged for your letter of October 10th, from Celebes, received a few days ago; in a laborious undertaking, sympathy is a valuable and real encouragement. By your letter and even still more by your paper ('On the law that has regulated the introduction of new species.' — Ann. Nat. Hist., 1855.) in the Annals, a year or more ago, I can plainly see that we have thought much alike and to a certain extent have come to similar conclusions. In regard to the Paper in the Annals, I agree to the truth of almost every word of your paper; and I dare say that you will agree with me that it is very rare to find oneself agreeing pretty closely with any theoretical paper; for it is lamentable how each man draws his own different conclusions from the very same facts. This summer will make the 20th year (!) since I opened my first note-book, on the question how and in what way do species and varieties differ from each other. I am now preparing my work for publication, but I find the subject so very large, that though I have written many chapters, I do not suppose I shall go to press for two years. I have never heard how long you intend staying in the Malay Archipelago; I wish I might profit by the publication of your Travels there before my work appears, for no doubt you will reap a large harvest of facts. I have acted already in accordance with your advice of keeping domestic varieties, and those appearing in a state of nature, distinct; but I have sometimes doubted of the wisdom of this, and therefore I am glad to be backed by your opinion. I must confess, however, I rather doubt the truth of the now very prevalent doctrine of all our domestic animals having descended from several wild stocks; though I do not doubt that it is so in some cases. I think there is rather better evidence on the sterility of hybrid animals than you seem to admit: and in regard to plants the collection of carefully recorded facts by Kolreuter and Gaertner (and Herbert,) is ENORMOUS. I most entirely agree with you on the little effects of "climatal conditions," which one sees referred to ad nauseam in all books: I suppose some very little effect must be attributed to such influences, but I fully believe that they are very slight. It is really IMPOSSIBLE to explain my views (in the compass of a letter), on the causes and means of variation in a state of nature; but I have slowly adopted a distinct and tangible idea, — whether true or false others must judge; for the firmest conviction of the truth of a doctrine by its author, seems, alas, not to be the slightest guarantee of truth!..

CHARLES DARWIN TO J.D. HOOKER. Moor Park, Saturday [May 2nd, 1857].

My dear Hooker,

You have shaved the hair off the Alpine plants pretty effectually. The case of the Anthyllis will make a "tie" with the believed case of Pyrenees plants becoming glabrous at low levels. If I DO find that I have marked such facts, I will lay the evidence before you. I wonder how the belief could have originated! Was it through final causes to keep the plants warm? Falconer in talk coupled the two facts of woolly Alpine plants and mammals. How candidly and meekly you took my Jeremiad on your severity to second-class men. After I had sent it off, an ugly little voice asked me, once or twice, how much of my noble defence of the poor in spirit and in fact, was owing to your having not seldom smashed favourite notions of my own. I silenced the ugly little voice with contempt, but it would whisper again and again. I sometimes despise myself as a poor compiler as heartily as you could do, though I do NOT despise my whole work, as I think there is enough known to lay a foundation for the discussion on the origin of species. I have been led to despise and laugh at myself as a compiler, for having put down that "Alpine plants have large flowers," and now perhaps I may write over these very words, "Alpine plants have small or apetalous flowers!"...

CHARLES DARWIN TO J.D. HOOKER. Down, [May] 16th [1857].

My dear Hooker,

You said — I hope honestly — that you did not dislike my asking questions on general points, you of course answering or not as time or inclination might serve. I find in the animal kingdom that the proposition that any part or organ developed normally (i.e., not a monstrosity) in a species in any HIGH or UNUSUAL degree, compared with the same part or organ in allied species, tends to be HIGHLY VARIABLE. I cannot doubt this from my mass of collected facts. To give an instance, the Cross-bill is very abnormal in the structure of its bill compared with other allied Fringillidae, and the beak is EMINENTLY VARIABLE. The Himantopus, remarkable from the wonderful length of its legs, is VERY variable in the length of its legs. I could give MANY most striking and curious illustrations in all classes; so many that I think it cannot be chance. But I have NONE in the vegetable kingdom, owing, as I believe, to my ignorance. If Nepenthes consisted of ONE or two species in a group with a pitcher developed, then I should have expected it to have been very variable; but I do not consider Nepenthes a case in point, for when a whole genus or group has an organ, however anomalous, I do not expect it to be variable, — it is only when one or few species differ greatly in some one part or organ from the forms CLOSELY ALLIED to it in all other respects, that I believe such part or organ to be highly variable. Will you turn this in your mind? It is an important apparent LAW (!) for me.

Ever yours, C. DARWIN.

P.S. — I do not know how far you will care to hear, but I find Moquin-Tandon treats in his 'Teratologie' on villosity of plants, and seems to attribute more to dryness than altitude; but seems to think that it must be admitted that mountain plants are villose, and that this villosity is only in part explained by De Candolle's remark that the dwarfed condition of mountain plants would condense the hairs, and so give them the APPEARANCE of being more hairy. He quotes Senebier, 'Physiologie Vegetale,' as authority — I suppose the first authority, for mountain plants being hairy.

If I could show positively that the endemic species were more hairy in dry districts, then the case of the varieties becoming more hairy in dry ground would be a fact for me.

CHARLES DARWIN TO J.D. HOOKER. Down, June 3rd [1857].

My dear Hooker,

I am going to enjoy myself by having a prose on my own subjects to you, and this is a greater enjoyment to me than you will readily understand, as I for months together do not open my mouth on Natural History. Your letter is of great value to me, and staggers me in regard to my proposition. I dare say the absence of botanical facts may in part be accounted for by the difficulty of measuring slight variations. Indeed, after writing, this occurred to me; for I have Crucianella stylosa coming into flower, and the pistil ought to be very variable in length, and thinking of this I at once felt how could one judge whether it was variable in any high degree. How different, for instance, from the beak of a bird! But I am not satisfied with this explanation, and am staggered. Yet I think there is something in the law; I have had so many instances, as the following: I wrote to Wollaston to ask him to run through the Madeira Beetles and tell me whether any one presented anything very anomalous in relation to its allies. He gave me a unique case of an enormous head in a female, and then I found in his book, already stated, that the size of the head was ASTONISHINGLY variable. Part of the difference with plants may be accounted for by many of my cases being secondary male or FEMALE characters, but then I have striking cases with hermaphrodite Cirripedes. The cases seem to me far too numerous for accidental coincidences, of great variability and abnormal development. I presume that you will not object to my putting a note saying that you had reflected over the case, and though one or two cases seemed to support, quite as many or more seemed wholly contradictory. This want of evidence is the more surprising to me, as generally I find any proposition more easily tested by observations in botanical works, which I have picked up, than in zoological works. I never dreamed that you had kept the subject at all before your mind. Altogether the case is one more of my MANY horrid puzzles. My observations, though on so infinitely a small scale, on the struggle for existence, begin to make me see a little clearer how the fight goes on. Out of sixteen kinds of seed sown on my meadow, fifteen have germinated, but now they are perishing at such a rate that I doubt whether more than one will flower. Here we have choking which has taken place likewise on a great scale, with plants not seedlings, in a bit of my lawn allowed to grow up. On the other hand, in a bit of ground, 2 by 3 feet, I have daily marked each seedling weed as it has appeared during March, April and May, and 357 have come up, and of these 277 have ALREADY been killed chiefly by slugs. By the way, at Moor Park, I saw rather a pretty case of the effects of animals on vegetation: there are enormous commons with clumps of old Scotch firs on the hills, and about eight or ten years ago some of these commons were enclosed, and all round the clumps nice young trees are springing up by the million, looking exactly as if planted, so many are of the same age. In other parts of the common, not yet enclosed, I looked for miles and not ONE young tree could be seen. I then went near (within quarter of a mile of the clumps) and looked closely in the heather, and there I found tens of thousands of young Scotch firs (thirty in one square yard) with their tops nibbled off by the few cattle which occasionally roam over these wretched heaths. One little tree, three inches high, by the rings appeared to be twenty-six years old, with a short stem about as thick as a stick of sealing-wax. What a wondrous problem it is, what a play of forces, determining the kind and proportion of each plant in a square yard of turf! It is to my mind truly wonderful. And yet we are pleased to wonder when some animal or plant becomes extinct.

I am so sorry that you will not be at the Club. I see Mrs. Hooker is going to Yarmouth; I trust that the health of your children is not the motive. Good-bye.

My dear Hooker, ever yours, C. DARWIN.

P.S. — I believe you are afraid to send me a ripe Edwardsia pod, for fear I should float it from New Zealand to Chile!!!

CHARLES DARWIN TO J.D. HOOKER. Down, June 5 [1857].

My dear Hooker,

I honour your conscientious care about the medals. (The Royal Society's medals.) Thank God! I am only an amateur (but a much interested one) on the subject.

It is an old notion of mine that more good is done by giving medals to younger men in the early part of their career, than as a mere reward to men whose scientific career is nearly finished. Whether medals ever do any good is a question which does not concern us, as there the medals are. I am almost inclined to think that I would rather lower the standard, and give medals to young workers than to old ones with no ESPECIAL claims. With regard to especial claims, I think it just deserving your attention, that if general claims are once admitted, it opens the door to great laxity in giving them. Think of the case of a very rich man, who aided SOLELY with his money, but to a grand extent — or such an inconceivable prodigy as a minister of the Crown who really cared for science. Would you give such men medals? Perhaps medals could not be better applied than EXCLUSIVELY to such men. I confess at present I incline to stick to especial claims which can be put down on paper...

I am much confounded by your showing that there are not obvious instances of my (or rather Waterhouse's) law of abnormal developments being highly variable. I have been thinking more of your remark about the difficulty of judging or comparing variability in plants from the great general variability of parts. I should look at the law as more completely smashed if you would turn in your mind for a little while for cases of great variability of an organ, and tell me whether it is moderately easy to pick out such cases; For IF THEY CAN BE PICKED OUT, and, notwithstanding, do not coincide with great or abnormal development, it would be a complete smasher. It is only beginning in your mind at the variability end of the question instead of at the abnormality end. PERHAPS cases in which a part is highly variable in all the species of a group should be excluded, as possibly being something distinct, and connected with the perplexing subject of polymorphism. Will you perfect your assistance by further considering, for a little, the subject this way?

I have been so much interested this morning in comparing all my notes on the variation of the several species of the genus Equus and the results of their crossing. Taking most strictly analogous facts amongst the blessed pigeons for my guide, I believe I can plainly see the colouring and marks of the grandfather of the Ass, Horse, Quagga, Hemionus and Zebra, some millions of generations ago! Should not I [have] sneer[ed] at any one who made such a remark to me a few years ago; but my evidence seems to me so good that I shall publish my vision at the end of my little discussion on this genus.

I have of late inundated you with my notions, you best of friends and philosophers.

Adios, C. DARWIN.

CHARLES DARWIN TO J.D. HOOKER. Moor Park, Farnham, June 25th [1857].

My dear Hooker,

This requires no answer, but I will ask you whenever we meet. Look at enclosed seedling gorses, especially one with the top knocked off. The leaves succeeding the cotyledons being almost clover-like in shape, seems to me feebly analogous to embryonic resemblances in young animals, as, for instance, the young lion being striped. I shall ask you whether this is so...(See 'Power of Movement in Plants,' page 414.)

Dr. Lane (The physician at Moor Park.) and wife, and mother-in-law, Lady Drysdale, are some of the nicest people I ever met.

I return home on the 30th. Good-bye, my dear Hooker.

Ever yours, C. DARWIN.

[Here follows a group of letters, of various dates, bearing on the question of large genera varying.]

CHARLES DARWIN TO J.D. HOOKER. March 11th [1858].

I was led to all this work by a remark of Fries, that the species in large genera were more closely related to each other than in small genera; and if this were so, seeing that varieties and species are so hardly distinguishable, I concluded that I should find more varieties in the large genera than in the small...Some day I hope you will read my short discussion on the whole subject. You have done me infinite service, whatever opinion I come to, in drawing my attention to at least the possibility or the probability of botanists recording more varieties in the large than in the small genera. It will be hard work for me to be candid in coming to my conclusion.

Ever yours, most truly, C. DARWIN.

P.S. — I shall be several weeks at my present job. The work has been turning out badly for me this morning, and I am sick at heart; and, oh! how I do hate species and varieties.

CHARLES DARWIN TO J.D. HOOKER. July 14th [1857?].

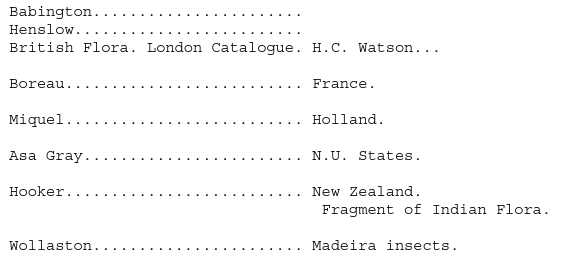

...I write now to supplicate most earnestly a favour, viz., the loan of "Boreau, Flore du centre de la France", either 1st or 2nd edition, last best; also "Flora Ratisbonensis," by Dr. Furnrohr, in 'Naturhist. Topographie von Regensburg, 1839.' If you can POSSIBLY spare them, will you send them at once to the enclosed address. If you have not them, will you send one line by return of post: as I must try whether Kippist (The late Mr. Kippist was at this time in charge of the Linnean Society's Library.) can anyhow find them, which I fear will be nearly impossible in the Linnean Library, in which I know they are.

I have been making some calculations about varieties, etc., and talking yesterday with Lubbock, he has pointed out to me the grossest blunder which I have made in principle, and which entails two or three weeks' lost work; and I am at a dead-lock till I have these books to go over again, and see what the result of calculation on the right principle is. I am the most miserable, bemuddled, stupid dog in all England, and am ready to cry with vexation at my blindness and presumption.

Ever yours, most miserably, C. DARWIN.

CHARLES DARWIN TO JOHN LUBBOCK. Down, [July] 14th [1857].

My dear Lubbock,

You have done me the greatest possible service in helping me to clarify my brains. If I am as muzzy on all subjects as I am on proportion and chance, — what a book I shall produce!

I have divided the New Zealand Flora as you suggested, there are 329 species in genera of 4 and upwards, and 323 in genera of 3 and less.

The 339 species have 51 species presenting one or more varieties. The 323 species have only 37. Proportionately (339: 323:: 51: 48.5) they ought to have had 48 1/2 species presenting vars. So that the case goes as I want it, but not strong enough, without it be general, for me to have much confidence in. I am quite convinced yours is the right way; I had thought of it, but should never have done it had it not been for my most fortunate conversation with you.

Un quite shocked to find how easily I am muddled, for I had before thought over the subject much, and concluded my way was fair. It is dreadfully erroneous.

What a disgraceful blunder you have saved me from. I heartily thank you.

Ever yours, C. DARWIN.

P.S. — It is enough to make me tear up all my MS. and give up in despair.

It will take me several weeks to go over all my materials. But oh, if you knew how thankful I am to you!

CHARLES DARWIN TO J.D. HOOKER. Down, August [1857].

My dear Hooker,

It is a horrid bore you cannot come soon, and I reproach myself that I did not write sooner. How busy you must be! with such a heap of botanists at Kew. Only think, I have just had a letter from Henslow, saying he will come here between 11th and 15th! Is not that grand? Many thanks about Furnrohr. I must humbly supplicate Kippist to search for it: he most kindly got Boreau for me.

I am got extremely interested in tabulating, according to mere size of genera, the species having any varieties marked by Greek letters or otherwise: the result (as far as I have yet gone) seems to me one of the most important arguments I have yet met with, that varieties are only small species — or species only strongly marked varieties. The subject is in many ways so very important for me; I wish much you would think of any well-worked Floras with from 1000-2000 species, with the varieties marked. It is good to have hair-splitters and lumpers. (Those who make many species are the "splitters," and those who make few are the "lumpers.") I have done, or am doing: —

Has not Koch published a good German Flora? Does he mark varieties? Could you send it me? Is there not some grand Russian Flora, which perhaps has varieties marked? The Floras ought to be well known.

I am in no hurry for a few weeks. Will you turn this in your head when, if ever, you have leisure? The subject is very important for my work, though I clearly see MANY causes of error...

CHARLES DARWIN TO ASA GRAY. Down, February 21st [1859].

My dear Gray,

My last letter begged no favour, this one does: but it will really cost you very little trouble to answer to me, and it will be of very GREAT service to me, owing to a remark made to me by Hooker, which I cannot credit, and which was suggested to him by one of my letters. He suggested my asking you, and I told him I would not give the least hint what he thought. I generally believe Hooker implicitly, but he is sometimes, I think, and he confesses it, rather over critical, and his ingenuity in discovering flaws seems to me admirable. Here is my question: — "Do you think that good botanists in drawing up a local Flora, whether small or large, or in making a Prodromus like De Candolle's, would almost universally, but unintentionally and unconsciously, tend to record (i.e., marking with Greek letters and giving short characters) varieties in the large or in the small genera? Or would the tendency be to record the varieties about equally in genera of all sizes? Are you yourself conscious on reflection that you have attended to, and recorded more carefully the varieties in large or small, or very small genera?"

I know what fleeting and trifling things varieties very often are; but my query applies to such as have been thought worth marking and recording. If you could screw time to send me ever so brief an answer to this, pretty soon, it would be a great service to me.

Yours most truly obliged, CH. DARWIN.

P.S. — Do you know whether any one has ever published any remarks on the geographical range of varieties of plants in comparison with the species to which they are supposed to belong? I have in vain tried to get some vague idea, and with the exception of a little information on this head given me by Mr. Watson in a paper on Land Shells in United States, I have quite failed; but perhaps it would be difficult for you to give me even a brief answer on this head, and if so I am not so unreasonable, I ASSURE YOU, as to expect it.

If you are writing to England soon, you could enclose other letters [for] me to forward.

Please observe the question is not whether there are more or fewer varieties in larger or smaller genera, but whether there is a stronger or weaker tendency in the minds of botanists to RECORD such in large or small genera.

CHARLES DARWIN TO J.D. HOOKER. Down, May 6th [1858].

...I send by this post my MS. on the "commonness," "range," and "variation" of species in large and small genera. You have undertaken a horrid job in so very kindly offering to read it, and I thank you warmly. I have just corrected the copy, and am disappointed in finding how tough and obscure it is; I cannot make it clearer, and at present I loathe the very sight of it. The style of course requires further correction, and if published I must try, but as yet see not how, to make it clearer.

If you have much to say and can have patience to consider the whole subject, I would meet you in London on the Phil. Club day, so as to save you the trouble of writing. For Heaven's sake, you stern and awful judge and sceptic, remember that my conclusions may be true, notwithstanding that Botanists may have recorded more varieties in large than in small genera. It seems to me a mere balancing of probabilities. Again I thank you most sincerely, but I fear you will find it a horrid job.

Ever yours, C. DARWIN.

P.S. — As usual, Hydropathy has made a man of me for a short time: I hope the sea will do Mrs. Hooker much good.