полная версия

полная версияThe Intelligence of Woman

Or perhaps it is a broader view, a more socialized one. Very young, the child is acquiring a vague sense of its responsibility to the race, is very early becoming a citizen. It is directed that way; it hears that liberty consists in doing what you like, providing you injure no other man. Its personality being encouraged to develop, the child acquires a higher opinion of itself, considers that it owes something to itself, that it has rights. Sacrifice is still inculcated in the child, but not so much because it is a moral duty as because it is mental discipline. The little boy is not told to give the chocolates to his little sister because she is a dear little thing, and he must not be cruel to her and make her cry; he is told that he must give her the chocolates because it is good for him to learn to give up something. That impulse is the impulse of Polycrates, who threw his ring into the sea. But, then, Polycrates had no luck. The child, more fortunate, is tending to realize itself as a person, and so, as it becomes more responsible, acquires tolerance; it makes allowances for its parents, it is kind, it realizes that its parents have not had its advantages. All that is very swollen-headed and unpleasant, but still I prefer it to the old attitude, to the time when voices were hushed and footsteps slowed when father's latchkey was heard in the lock. To the child the parent is becoming a person instead of the God of Wrath; a person with rights, but not a person to whom everything must be given up. Sacrifice is out of date, and in the child as well as in the elders there is a denial of the dream of Ellen Sturges Cooper, for few wake up and find that life is duty. My life, my personality – all that has sprung from Stirner, from Nietzsche, from the great modern reaction against socialism and uniformity; it is the assertion of the individual. It is often harsh; the daughter who used to take her father for a walk now sends the dog. But still it is necessary; old hens make good soup. I do not think that this has killed love, for love can coexist with mutual forbearance, however much Doctor Johnson may have doubted it. Doctor Johnson was the bad old man of the English family, and I do not suppose that anybody will agree that

"If the man who turnips criesCry not when his father dies,'Tis a proof that he had ratherHave a turnip than his father."A possible sentiment in an older generation, but sentiments, like generations, grow out of date; they are swept out by new ideas and new rejections – rejection of religion, rejection of morals. We tend toward an agnostic world, with a high philosophical morality; we have attained as yet neither agnosticism nor high morality, but the child is shaking off the ready-made precepts of the faiths and the Smilesian theories. It is unwillingly bound by the ordinances of a forgotten alien race; as a puling child, carried in a basket by an eagle, like the tiny builders of Ecbatana, it calls for bricks and mortar with which to build the airy castle of the future.

3

As a house divided against itself, the family falls. It protests, it hugs that from which it suffered; it protests in speech, in the newspapers, that still it is united. The clan is dead, and blood is not as thick as marmalade. There are countries where the link is strong, as in France, for instance. I quote from a recent and realistic novel the words of a mother speaking of her young married daughter:

"Every Tuesday we dine at my mother's, and every Thursday at my mother-in-law's. Of course, now, at least once a week we go to Madame de Castelac; later on I shall expect Pauline and her husband every Wednesday."

"That is a pity," said Sorel. "That leaves three days."

"Oh, there are other calls. Every week my mother comes to us the same evening as does my father-in-law, but that is quite informal."

Family dinners are rare in England. They flourish only at weddings and at funerals, especially at funerals, for mankind collected enjoys woe. But other occasions – birthdays, Christmas – are shunned; Christmas especially, in spite of Dickens and Mr. Chesterton, is not what it was, for its quondam victims, having fewer children, and being less bound to their aunts' apron strings, go away to the seaside, or stay at home and hide. That is a general change, and many modern factors, such as travel, intercourse with strangers, emigration, have shown the family that there are other places than home, until some of them have begun to think that "East or West, home's worst." There is a frigidity among the relations in the home, a disinclination to call one's mother-in-law "Mother." Indeed, relations-in-law are no longer relatives; the two families do not immediately after the wedding call one another Kitty or Tom. The acquired family is merely a sub-family, and often the grouping resembles that of the Montagues and the Capulets, if Romeo and Juliet had married. Mrs. Herbert said, charmingly, in Garden Oats, "Our in-laws are our strained relations."

With the closeness of the family goes the regard for the name, once so strong. I feel sure that in all seriousness, round about 1850, a father may have said to his son that he was disgracing the name of Smith. Now he may almost disgrace the name of FitzArundel for all anybody cares. There was a time when it was thought criminal that a man should become a bankrupt, but few families will now mortgage their estate to prevent a distant member's appearance before the official receiver. The name of the family is now merely generic, and the bold young girl of to-morrow will say, "My father began life as a forger and was ultimately hanged, but that shouldn't bother you, should it?" Much of that deliquescence is due to the factory system, for it opened opportunities to all, which many took, raised men high in the scale of wealth; one brother might be a millionaire in Manchester, while another tended a bar in Liverpool. Sometimes the rich member of the family came back, such as the uncle who returned from America with a fortune, in a state of sentimental generosity, but most of the time it has meant that the family split into those who keep their carriage and those who take the tram. Perhaps Cervantes did not exaggerate when saying that there are only two families: Have-Much and Have-Little.

4

What the future reserves I disincline to prophesy. It is enough to point to tendencies, and to say, "Along this road we go, we know not whither." But of one thing I feel certain: the family will not become closer, for the individualistic tendency of man leads to instinctive rebellion; his latent anarchism to isolate him from his fellows. There is a growing rebellion among women against the thrall of motherhood, which, however delightful it may be, is a thrall – the velvet-coated yoke is a yoke still. I do not suppose that the mothers of the future will unanimously deposit their babies in the municipal crèche. But I do believe that with the growth of coöperative households, and especially of that quite new class, the skilled Princess Christian or Norland nurses, there will be a delegation of responsibility from the mother to the expert. It will go down to the poor as well as to the rich. Already we have district nurses for the poor, and I do not see why, as we realize more and more the value of young life, there should not be district kindergartens. They would remove the child still more from its home; they would throw it in contact with creatures of its own age in its very earliest years, prepare it for school, place it in an atmosphere where it must stand by itself among others who will praise or blame without special consideration, for they are strangers to it and do not bear its name.

I suspect, too, that marriage will be freer; it will not be made more easy or more difficult, but greater facilities will be given for divorce so that human beings may no longer be bound together in dislike, because they once committed the crime of loving unwisely. This, too, must loosen the family link, to-day still strong because people know that it is so hard to break it. It will be a conditional link when it can easily be done away with, a link that will be maintained only on terms of good behavior on both sides. The marriage service will need a new clause; we shall have to swear to be agreeable. The relation between husband and wife must change more. Conjugal tyranny still exists in a country such as England where the wife is not co-guardian of the child, for during his wife's lifetime a husband may remove her child into another country, refuse her access save at the price of a costly and uncertain legal action. The child itself must have rights. At present, all the rights it has are to such food as its parents will give it; it needs very gross cruelty before a man can be convicted of starving or neglecting his child. And when that child is what they call grown up – that is to say, sixteen – in practice it loses all its rights, must come out and fend for itself. I suspect that that will not last indefinitely, and that the new race will have upon the old race the claim that owing to the old race it was born. A socialized life is coming where there will be less freedom for those who are unfit to be free, those who do not feel categorical impulses, the impulse to treat wife and child gently and procure their happiness. Men will not indefinitely draw their pay on a Friday and drink half of it by Sunday night. Their wages will be subject to liens corresponding to the number of their children. These liens may not be light, and may extend long beyond the nominal majority of the child. I suspect that after sixteen, or some other early age, children will, if they choose, be entitled to leave home for some municipal hostel where for a while their parents will be compelled to pay for their support. It will be asked, "Why should a parent pay for the support of a child who will not live in his house?" It seems to me that the chief reply is, "Why did you have that child?" There is another, too: "By what right should this creature for whom you are responsible be tied to a house into which it has been called unconsulted? Why should it submit to your moral and religious views? to your friends? to your wall-paper?" It is a strong case, and I believe that, as time goes on and the law is strengthened, the young will more and more tend to leave their homes. In good, liberal homes they will stay, but the others they will abandon, and I believe that no social philosopher will regret that children should leave homes where they stay only because they are fed and not because they love.

So, flying apart by a sort of centrifugal force, the family will become looser and looser, until it exists only for those who care for one another enough to maintain the association. It cannot remain as it is, with its right of insult, its claim to society; we can have no more slave daughters and slave wives, nor shall we chain together people who spy out one another's loves and crush one another's youth. The family is immortal, but the immortals have many incarnations – from Pan and Bacchus sprang Lucifer, Son of the Morning. There is a time to come – better than this because it is to come – when the family, humanized, will be human.

VII

SOME NOTES ON MARRIAGE

1

The questioning mind, sole apparatus of the socio-psychologist, has of late years often concerned itself with marriage. Marriage always was discussed, long before Mrs. Mona Caird suggested in the respectable 'eighties that it might be a failure, but it is certain that with the coming of Mr. Bernard Shaw the institution which was questioned grew almost questionable. Indeed, marriage was so much attacked that it almost became popular, and some believe that the war may cut it free from the stake of martyrdom. Perhaps, but setting aside all prophecies, revolts and sermons, one thing does appear: marriage is on its trial before a hesitating jury. The judge has set this jury several questions: Is marriage a normal institution? Is it so normal as to deserve to continue in a state of civilization? given that civilization's function is to crush nature.

A thing is not necessarily good because it exists, for scarlet fever, nationality, art critics, and black beetles exist, yet all will be rooted out in the course of enlightenment. Marriage may be an invention of the male to secure himself a woman freehold, or, at least, in fee simple. It may be an invention of the female designed to secure a somewhat tyrannical protection and a precarious sustenance. Marriage may be afflicted with inherent diseases, with antiquity, with spiritual indigestion, or starvation: among these confusions the socio-psychologist, swaying between the solidities of polygamy and the shadows of theosophical union, loses all idea of the norm. There may be no norm, either in Christian marriage, polygamy, Meredithian marriage leases; there may be a norm only in the human aspiration to utility and to happiness.

For we know very little save the aimlessness of a life that may be paradise, or its vestibule, or an instalment of some other region. Still there is a key, no doubt: the will to happiness, which, alas! opens doors most often into empty rooms. It is the search for happiness that has envenomed marriage and made it so difficult to bear, because in the first rapture it is so hard to realize that there are no ways of living, but only ways of dying more or less agreeably.

Personally, I believe that with all its faults, with its crudity, its stupidity shot with pain, marriage responds to a human need to live together and to foster the species, and that though we will make it easier and approach free union, we shall always have something of the sort. And so, because I believe it eternal, I think it necessary.

But why does it fare so ill? Why is it that when we see in a restaurant a middle-aged couple, mutually interested and gay, we say: "I wonder if they are married?" Why do so many marriages persist when the love knot slips, and bandages fall away from the eyes? Strange cases come to my mind: M 6 and M 22, always apart, except to quarrel, meanly jealous, jealously mean, yet full of affability – to strangers; M 4 and many others, all poor, where at once the wife has decayed; when you see youth struggling in vain on the features under the cheap hat, you need not look at the left hand: she is married. It is true that however much they may decay in pride of body and pride of life, when all allowances are made for outer gaiety and grace, the married of forty are a sounder, deeper folk than their celibate contemporaries. Often bled white by self-sacrifice, they have always learnt a little of the world's lesson, which is to know how to live without happiness. They may have been vampires, but they have not gone to sleep in the cotton wool of their celibacy. Even hateful, the other sex has meant something to them. It has meant that the woman must hush the children because father has come home, but it has also meant that she must change her frock, because even father is a man. It has taught the man that there are flowers in the world, which so few bachelors know; it has taught the woman to interest herself in something more than a fried egg, if only to win the favor of her lord. Marriage may not teach the wish to please, but it teaches the avoidance of offence, which, in a civilization governed by negative commandments, is the root of private citizenship.

2

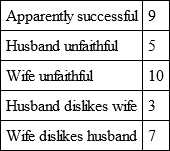

For the closer examination of the marriage problem, I am considering altogether one hundred and fifty cases; my acquaintance with them varies between intimate and slight. I have thrown out one hundred and sixteen cases where the evidence is inadequate: the following are therefore not loose generalizations, but one thing I assert: those one hundred and sixteen cases do not contain a successful marriage. Out of the remaining thirty-four, the following results arise:

Success is a vague word, and I attempt no definition, but we know a happy marriage when we see it, as we do a work of art.

It should be observed that when one or both parties are unfaithful, the marriage is not always unsuccessful, but it generally is; moreover, there are difficulties in establishing proportion, for women are infinitely more confidential on this subject than are men; they also frequently exaggerate dislike, which men cloak in indifference. Still, making all these allowances, I am unable to find more than nine cases of success, say six per cent. This percentage gives rise to platitudinous thoughts on the horrid gamble of life.

Two main conclusions appear to follow: that more wives than husbands break their marriage vows, and (this may be a cause as well as an effect) that more wives than husbands are disappointed in their hopes. This is natural enough, as nearly all women come ignorant to a state requiring cool knowledge and armored only with illusion against truth, while men enter it with experience, if not with tolerance born of disappointment. I realize that these two conclusions are opposed to the popular belief that a good home and a child or two are enough to make a woman content. (A bad home and a child or nine is not considered by the popular mind.)

There is no male clamor against marriage, from which one might conclude that man is fairly well served. No doubt he attaches less weight to the link; even love matters to him less than to women. I do not want to exaggerate, for Romeo is a peer to Juliet, but it is possible to conceive Romeo on the Stock Exchange, very busy in pursuit of money and rank, while Juliet would remain merely Juliet. Juliet is not on the Stock Exchange. If business is good, she has nothing to do, and if Satan does not turn her hands to evil works, he may turn them to good ones, which will not improve matters very much. Juliet, idle, can do nothing but seek a deep and satisfying love: mostly it is a lifelong occupation. All this makes Juliet very difficult, and no astronomer will give her the moon.

Romeo is in better plight, for he makes less demands. Let Juliet be a good housekeeper, fairly good looking and good tempered; not too stupid, so as to understand him; not too clever, so that he may understand her; such that he may think her as good as other men's wives, and he is satisfied. The sentimental business is done; it is "Farewell! Farewell! ye lovely young girls, we're off to Rio Bay." So to work – to money – to ambition – to sport – to anything – but Juliet. While he forgets her, the modern woman grows every day more attractive, more intellectually vivid. She demands of her partner that he should give her stimulants, and he gives her soporifics. She asks him for far too much; she is cruel, she is unjust, and she is magnificent. She has not the many children on whom in simpler days her mother used to vent an exacting affection, so she vents it on her husband.

Yet it is not at first sight evident why so easily in England a lover turns into a husband, that is to say, into a vaguely disagreeable person who can be coaxed into paying bills. I suspect there are many influences corrupting marriage, and most of them are mutual in their action; they are of the essence of the contract; they are the mental reservations of the marriage oath. So far as I can see, they fall into sixteen classes: —

1. The waning of physical attraction.

2. Diverging tastes.

3. Being too much together.

4. Being too much apart. (There is no pleasing this institution.)

5. The sense of mutual property.

6. The sense of the irremediable.

7. Children.

8. The cost of living.

9. Rivalry.

10. Polygamy in men and "second blooming" in women.

11. Coarseness and talkativeness.

12. Sulkiness.

13. Dull lives.

14. Petty intolerance.

15. Stupidity.

16. Humour and aggressiveness.

There are other influences, but they are not easily ascertained; sometimes they are subtle.

M 28 said to me: "My husband's grievance against me is that I have a cook who can't cook; my grievance against him is that he married me."

Indeed, sentiment and the scullery painfully represent the divergence of the two sexes. One should not exaggerate the scullery; the philosopher who said "Feed the brute" was not entirely wrong, but it is quite easy for a woman to ignore the emotional pabulum that many a man requires. It is quite true that "the lover in the husband may be lost", but very few women realize that the wife can blot out the mistress. Case M 19 confessed that she always wore out her old clothes at home, and she was surprised when I suggested that though her husband was no critic of clothes, he might often wonder why she did not look as well as other women. Many modern wives know this; in them the desire to please never quite dies; between lovers, it is violent and continuous; between husband and wife, it is sometimes maintained only by shame and self-respect: there are old slippers that one can't wear, even before one's husband.

The problem arises very early with the waning of physical attraction. I am not thinking only of the bad and hasty marriages so frequent in young America, but of the English marriages, where both parties come together in a state of sentimental excitement born of ignorance and rather puritanical restraint. Europeans wed less wisely than the Hindoo and the Turk, for these realize their wives as Woman. Generally they have never seen a woman of their own class, and so she is a revelation, she is indeed the bulbul, while he, being the first, is the King of men. But the Europeans have mixed too freely, they have skimmed, they have flirted, they have been so ashamed of true emotion that they have made the Song of Solomon into a vaudeville ditty. They have watered the wine of life.

So when at last the wine of life is poured out, the draught is not new, for they have quaffed before many an adulterated potion and have long pretended that the wine of life is milk. For a moment there is a difference, and they recognize that the incredible can happen; each thinks the time has come:

"Wenn ich dem Augenblick werd sagen:Verweile doch, du bist so schön."Then the false exaltation subsides: not even a saint could stand a daily revelation; the revelation becomes a sacramental service, the sacramental service a routine, and then, little by little, there is nothing. But nature, as usual abhorring a vacuum, does not allow the newly opened eyes to dwell upon a void; it leaves them clear, it allows them to compare. One day two demi-gods gaze into the eyes of two mortals and resent their fugitive quality. Another day two mortals gaze into the eyes of two others, whom suddenly they discover to be demi-gods. Some resist the trickery of nature, some succumb, some are fortunate, some are strong. But the two who once were united are divorced by the three judges of the Human Supreme Court: Contrast, Habit, and Change.

Time cures no ills; sometimes it provides poultices, often salt, for wounds. Time gives man his work, which he always had, but did not realize in the days of his enchantment; but to woman time seldom offers anything except her old drug, love. Oh! there are other things, children, visiting cards, frocks, skating rinks, Christian Science teas, and Saturday anagrams, but all these are but froth. Brilliant, worldly, hard-eyed, urgent, pleasure-drugged, she still believes there is an exquisite reply to the question:

"Will the love you are so rich inLight a fire in the kitchen,And will the little God of Love turn the spit, spit, spit?"Only the little God of Love does not call, and the butcher does.

It is her own fault. It is always one's own fault when one has illusions, though it is, in a way, one's privilege. She is attracted to a strange man because he is tall and beautiful, or short and ugly and has a clever head, or looks like a barber; he comes of different stock, from another country, out of another class – and these two strangers suddenly attempt to blend a total of, say, fifty-five years of different lives into a single one! Gold will melt, but it needs a very fierce fire, and as soon as the fire is withdrawn, it hardens again. Seldom is there anything to make it fluid once more, for the attraction, once primary, grows with habit commonplace, with contrast unsatisfactory, with growth unsuitable. The lovers are twenty, then in love, then old.

It is true that habit affects man not in the same way as it does woman; after conquest man seems to grow indifferent, while, curiously enough, habit often binds woman closer to man, breeds in her one single fierce desire: to make him love her more. Man buys cash down, woman on the instalment plan, horribly suspecting now and then that she is really buying on the hire system. A rather literary case, Case M 11, said to me: "I am much more in love with him than I was in the beginning; he seemed so strange and hard then. Now I love him, but … he seems tired of me; he knows me too well. I wonder whether we only fall in love with men just about the time that they get sick of us."