полная версия

полная версияThoughts on General and Partial Inoculations

Thomas Dimsdale

Thoughts on General and Partial Inoculations / Containing a translation of two treatises written when the / author was at Petersburg, and published there, by Command / of her Imperial Majesty, in the Russian Language

INTRODUCTION

To preserve the lives and health of the inferior part of mankind has been an object carefully attended to in all civilized and well regulated states, not only from motives of compassion, but because it has been plainly demonstrated that it is the interest of the wealthy in every nation to encourage population, and provide for the wants of the poor.

One would indeed, on the first thought presume, that the unavoidable necessities of the indigent would be voluntarily relieved out of the abundance of their opulent neighbours; but the number of laws that have been made for the provision of the poor, are proofs of the futility of this expectation, and the necessity of compulsion.

Among the many objects that have been provided for, it seems matter of astonishment that no one has ever pointed out the Small Pox as a distemper, whose destructive consequences might be in great measure prevented by the interposition of Legislature, and the assistance that would be certainly afforded from private charity.

It is now above fifty years since Inoculation was introduced into this country, and like other new institutions was then opposed; but at present, though it may be impossible to define the numbers that are yearly inoculated, it is certain that most of the wealthy approve and avail themselves of the practice: yet we view the Bills of Mortality with unconcern, though they demonstrate that the number of deaths from this disease is considerably increased; and with the affecting circumstance, that they are probably of the younger part of the people.

Although this matter has not been attended to here, it did not escape the penetration of the Empress of Russia; who, with a regard to the happiness of her people that deserves much greater commendation than I am able to bestow, was extremely solicitous to render Inoculation general among her subjects: and it was with a view to this that soon after the recovery of the Empress and Grand Duke from this operation, her Majesty was pleased to command me to write their cases, with the principal occurrences during the Inoculation, from an idea that being published they would tend to the removal of prejudices, and the advancement of a practice she had much at heart to encourage.

Her Imperial Majesty also frequently did me the honor to converse freely on several points respecting the natural Small Pox and Inoculation; and having been pleased to approve of the manner in which her enquiries and doubts were answered, I was afterwards commanded at different times to give in writing the substance of what had been advanced on these occasions. These orders were obeyed, the tracts translated into the Russian language, and as I imagined, were only intended for the perusal of the Empress. But in the year 1770, my treatise on Inoculation, with the following tracts, was published at Petersburg by her Majesty’s command:

I. An Account of the Inoculation for the Small Pox of her Imperial Majesty, Autocratrix of all the Russias.

II. An Account of the Inoculation for the Small Pox of his Imperial Highness the Grand Duke, the Heir of all the Russias, by Baron Thomas Dimsdale, first Physician to her Imperial Majesty.

III. Remarks on the Book, intitled, The present Method of Inoculating for the Small Pox, written by the Author now at St. Petersburg.

IV. A short Description of the Methods proposed for extending the salutary Practice of Inoculation through the whole Russian Empire.

V. A short Estimate of the Numbers of those who die of the natural Small Pox, with a View to demonstrate the Advantages that may accrue to Russia from the Practice of Inoculation, &c.

A translation of these tracts, with some further remarks on Inoculation, and a relation of my journey to Russia, has been preparing for the Press; but on some accounts unnecessary to be entered on here, is deferred.

Indeed, my appearance as a writer now is earlier than I intended, on account of a plan that I have seen of a Dispensary for inoculating the poor of London at their own houses, in which some plausible reasons for such an establishment are advanced; but I think they are much more specious than substantial; and that the plan itself is fraught with very dangerous consequences to the community, and not like to answer any good purpose if put in execution. Wherefore I thought it a duty owing to the public to publish these sentiments on the subject, that none should inadvertently misapply their charity so as to do mischief when good was intended.

In pursuance of this design, it seemed not improper to begin with the two last of the tracts that were wrote at Petersburg in the year 1768, as my opinions on the subjects treated of remain the same as at that time. But I desire that what is advanced in them, or may be found in the sequel, that tends to discountenance the practice of Inoculation by persons who have not had a medical education, may not be construed as a design to affect any of the family to whose mode of practice Inoculation is indebted for some considerable improvements; nothing can be farther from my intention, for I have been at all times disposed to do them justice, and allow all the merit that is their due.

In fact, I am an advocate for Inoculation; and wish the design of extending the benefit to the poor may be so conducted, as to afford its enemies as few opportunities of objecting to it on any solid ground as possible; and that the affair may be so well understood, as to make it plain in what manner charitably disposed persons may most usefully employ their benevolence.

A Description of the METHODS PROPOSED

For extending the salutary practice of Inoculation through the whole Russian Empire.

Written at Petersburg by her Imperial Majesty’s first Physician Baron Thomas Dimsdale.

In obedience to the orders received from her Imperial Majesty, I shall endeavour to demonstrate in a clear and concise manner the destructive effects of the Small Pox in the natural way, and the safety and advantage of Inoculation, even when performed after the old manner; and afterwards exhibit the improvement of the method, being the same which is now introduced into this great empire.

It will not be in my power to execute this plan with the accuracy I could wish, being engaged in an employment that demands much time and attention. But I will use my best endeavours to describe in the first place a method of propagating the practice of Inoculation, so that it may not be dangerous to those in the neighbourhood, who, either on account of bad health, age, prejudice, or other reasons, are unwilling to submit to the operation, and at the same time render it salutary to such as are proper objects and approve of it.

It is not to be supposed that the method now practised in England so successfully, can be received in Russia without some alteration. The experiments however which I have made in England, in order to ascertain the most commodious manner of conducting the affair, may be of use here; which I shall therefore describe as clearly as possible.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *In the original published in Russia, there followed a circumstantial account of the house I had built for the accommodation of my patients in England, and the manner of conducting the process, &c. there; which, as it would be of no consequence or use to insert in this translation, I have omitted.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *One, and indeed no inconsiderable advantage derived from a plan of this sort is, that by collecting all the patients together in one house, the physician will be enabled to attend a great number at the same time in a proper manner, and also to pay particular attention to such as may more immediately require his assistance.

And it is of no small importance to those who have been inoculated, that the necessary regulations in respect to regimen, as well as every other circumstance that requires the physician’s attention, may here be properly observed.

There is likewise another advantage obtained by this method, that, with proper caution, the Small Pox will not be communicated to others in the natural way of infection.

Notwithstanding all these conveniencies it will doubtless happen here, as it did in my neighbourhood, that many persons of distinction will rather prefer the inoculation of their families at their own houses. In this case it is submitted to the wisdom of government, whether it would not be proper to give orders that such persons should give public notice of their intention to inoculate, mentioning the time when the operation is to be performed, and also of their perfect recovery. By these means such as have not had the Small Pox, will have it in their power to avoid the infection.

So much with regard to the accommodation of persons of rank, who may be inoculated under one or the other abovementioned regulations. But the poor cannot enjoy those advantages. Humanity however and the interest of the state equally demand, that all possible attention should be bestowed for their assistance and preservation.

In order to attain this end, I know of no better or more certain method than that which I followed, on charitable motives only, in my own neighbourhood, by inoculating all the inhabitants of a village who had never had the Small Pox, on the same day: and, if this be performed in a proper manner, they might be all duly visited, and proper medicines administered at a moderate expence, and the whole be over in about three weeks: after which, this village would have nothing to apprehend from the Small Pox for some years. According to this plan, it will be unavoidably necessary that every child should be inoculated for the Small Pox soon after its birth, or that inoculation should be performed in every town or village once in five or six years. This last method I would rather recommend, and therefore, in order to make this proposal perfectly intelligible, I shall endeavour to explain it more particularly.

A list of the names and ages of such inhabitants of every town and village as have not had the Small Pox, is the first necessary step to be taken; and marks should be made against the names of those who on account of their ill state of health, or other reasons, are not thought fit subjects for the operation in the judgment of the inoculator; and such persons should be provided with a separate place of abode, where they may not be in danger of receiving the infection: the rest should be collected together in one place, inoculated at one time, and proper medicines, with directions specifying the time and manner in which they are to be taken, should be distributed to each individual. On the fourth day after the inoculation they should again be assembled together, the punctures examined, and such farther medicines given as the inoculator may think proper. After the seventh the patients should be examined daily; for from that time to the eleventh, or perhaps fourteenth, is a period that requires more particular attention. During the whole of this time, and indeed throughout the whole process, the sick may continue at their own houses. And it may be reasonably presumed, that there will be a sufficient number of such as are but slightly indisposed, who may be able to assist the others, so as to make the expence and trouble of nurses unnecessary. But we must also suppose, that of the very great number inoculated there will be some who may have the disease severely, or whose cases may require more constant attendance than they can possibly have at their own habitations. To provide for such extraordinary instances, therefore, a proper house and other conveniencies should be previously appointed, to which they should be removed when thought necessary.

It will be impossible to determine precisely how many patients may want such attendance, and consequently difficult to provide exactly the necessary accommodations; but I imagine there will not be more than four or five out of one hundred.

The diet of all should consist of vegetables, milk, bread, and the like; and in some cases a little mutton-broth may be allowed. The drink should be nothing but water, unless by the particular direction of the inoculator.

But in order to secure the observance of this regimen more exactly, all salted provision and every kind of strong liquor ought to be removed from the place, and every necessary precaution taken to prevent the patients from procuring any. In respect to medicines, the prescriptions being agreed on by the faculty, a sufficient quantity should be prepared, and proper doses; agreeable to the different age and constitution, put up separately, and distributed by the inoculator among the patients, with directions in what manner they should be administered; and their recovery should be completed with some proper purgative.

A licence or exclusive permission ought to be granted to such physicians or surgeons as undertake to inoculate for the Small Pox; for the mischief arising from the practice of inoculation by the illiterate and ignorant is beyond conception1. Such persons, instead of confining the infection within narrow limits, too often, through want of skill or honesty, are the means of propagating it, to the great terror of many people, the fatal consequences of which, and the destructive tokens, remain in many places in England. For besides the dreadful mortality which the disease itself has occasioned, it has often proved the source of discord and contention among neighbours, and disturbed that harmony and friendship which had before subsisted among the inhabitants.

To conclude, I beg this small treatise may be considered only as an imperfect sketch drawn up in haste; but if it should be approved of, and her Imperial Majesty be pleased to command me to enter into farther particulars, I will employ my utmost endeavours to render it more perfect, and also assist in the execution of any part of what has been therein proposed.

A short estimate of the number of those who die of the natural Small Pox, with a view to demonstrate the advantages that may accrue to Russia, from the practice of inoculation.

It is needless to expatiate upon the havock which the Small Pox makes in most parts of the known world: probably there is not a country, city, or smaller community, which has not experienced its devastations in its turn. The very idea of it is insupportable; but its real effects, in places unapprised and unacquainted with the proper treatment and remedies against it, are not less general and fatal than the plague itself.

Though this fact is generally allowed, yet many, I think, are ignorant of the immense loss mankind sustains by this distemper. It may not be amiss therefore to shew, from well attested accounts, the proportion of persons who die of the natural Small Pox: for which purpose it will be necessary to chuse some country or city where an exact register of the births and deaths, as well as an accurate list of diseases, is regularly kept.

Dr. Jurin, secretary to the Royal Society in London, carried this into execution in 1722, soon after Inoculation had been introduced into England, being desirous of shewing the different effects of the natural and inoculated Small Pox.

I shall not here insert all that was published by this ingenious author, as the whole may be found in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, under № 374. The following extract will be sufficient for my present purpose.

The Doctor for forty-two years selected from the Bills of Mortality in London, such as died there of the Small Pox and other distempers. His observation may appear perhaps somewhat extraordinary: nevertheless he makes it plain, that out of 1000 infants, 386 die under two years of age, which is considerably more than one third. He then deducts such as he supposes die of the diseases natural to infancy; and afterwards proceeds to demonstrate, that if the whole bulk of mankind be taken at the age of two years, the eighth part will die of the natural Small Pox; and that of such as have it in the natural way, one in five or six dies.

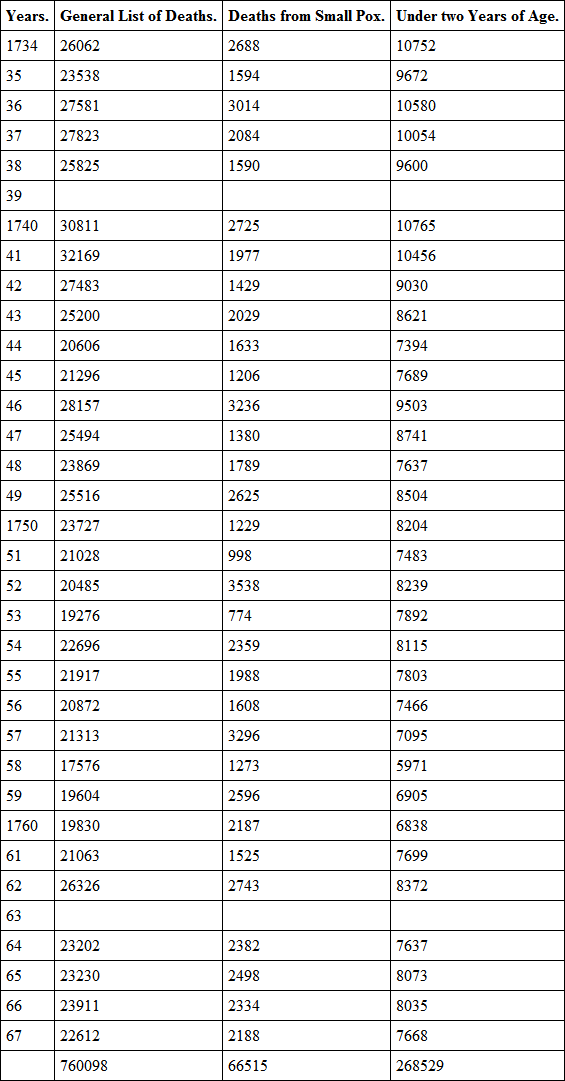

With respect to my own calculations on this subject, I endeavoured to find out whether the Small Pox proved equally fatal after the time mentioned by the Doctor. With this view, before I left England, I procured the Bills of Mortality of the City of London for the last thirty-four years, excepting two, which could not be found. Of these I made a table, which I have added at the end of this treatise. I was surprized to find the number for these thirty-two years past tally so exactly with the observations made by Dr. Jurin.

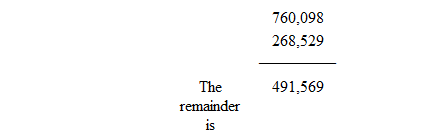

On examining the table it appears, that within these last thirty-two years 760,098 persons have died, and of those 268,529 have been infants under two years of age, which agrees with Dr. Jurin’s calculation, in being rather more than one-third of the whole.

I suppose, with Dr. Jurin, that the deaths of these were occasioned by different diseases incidental to infancy, and I deduct them out of the whole number, viz.

It appears likewise that in the same course of time there died of the Small Pox 66,515, which confirms Dr. Jurin’s account, and indeed exceeds the eighth part. Hence we may fairly conclude, that in general the Small Pox carried off the eighth part of those who died in London in the period abovementioned. I procured also the best accounts I possibly could of the whole number of those who had had the disease from places where the Small Pox had raged most, and found, that near one out of five died who had had the disease in the natural way. This also agrees with Dr. Jurin’s observations. We see then that even in London, where the climate is temperate, the disease well known, and the treatment of the sick very ably conducted, this single disease destroyed more than the eighth part of the inhabitants.

But if we turn our eyes towards other dominions, and give credit to the accounts told us, we shall find the disease still more fatal, and in some cities it is almost as destructive as the plague.

It is impossible for me to ascertain with any degree of certainty, the precise number of persons who die annually of the Small Pox in Russia. I am persuaded however, both from good intelligence as well as my own observations, that it is exceeding fatal here. Though I cannot confirm this assertion by proofs, yet from some conversation with the learned I am credibly informed, that of those who have the Small Pox in the natural way one-half die, including the rich and poor.

It seems hardly necessary to shew, how much the riches and strength of states depend upon the number of inhabitants. But perhaps there is not any country in which the certainty of this position is more indisputable than in Russia; for not only the strength of the empire, but the riches of every individual also, must be in proportion to the degree of population. If therefore in London, which enjoys the many advantages already recited, more than 2000 persons die annually of the Small Pox, we may surely suppose, that the loss which Russia in its whole extent sustains by this distemper in the same space of time, amounts to two millions of souls. And this havock must greatly retard the increase of the human species.

There are some diseases peculiar to old age, which terminate a life almost entirely spent, and totally useless to the community.

Such diseases, considered in a political sense, are not hurtful to the state. But the Small Pox spreads destruction chiefly upon the younger part of the species, from whose labours in their several callings the public might otherwise have expected advantages beyond all computation. The disappointment and loss incurred is of course neither to be calculated nor conceived.

A discourse upon this subject might be extended to a great length; but it seems unnecessary to enlarge, especially when I consider to whose judgment this essay is with all humility submitted.

The public, I am persuaded, must be sufficiently convinced from fact and demonstration, that Inoculation is the only means of preventing the mischiefs arising from the Small Pox.

In a former treatise I have laid down a plan for an effectual method of general practice, by which the spreading of the natural Small Pox will be prevented, and the cure of the inoculated rendered as easy and safe as possible to the patient.

I have therefore nothing more to add but my wishes, that the empire of Russia may meet with the utmost success from this discovery, under the reign of so illustrious and beneficent a Sovereign.

An objection to the practice of Inoculation considered

From the time that Inoculation was introduced into this country one may date the opposition to its practice; many learned and ingenious men soon entered the field against it, and were encountered by others of equal abilities in its defence. The questions were warmly agitated, and in a short time foreigners of great name became authors on both sides. But the strength of argument on the part of the defenders of Inoculation, supported by the good success of the practice, hath almost silenced opposition; and the concurrence of the courts of Petersburg, Vienna, and France, who have submitted to the operZation, and by their illustrious examples encouraged its progress in their dominions, will probably close the dispute in its favour.

One objection alone seems not to have been satisfactorily removed, which, although it does not relate to the safety or health of the patient, is yet of great importance to the community, and well deserves the most attentive consideration.

You have, say the objectors, produced accurate and satisfactory accounts and calculations of the alarming proportion of deaths that happen from the natural Small Pox, and also proved, that the loss sustained under Inoculation is inconsiderable. But admitting what you have advanced to be true, whence comes it that the same Bills of Mortality to which you appeal, prove also a certain increase instead of a diminution of deaths from the Small Pox, and that for such a series of years as to leave no room to dispute the fact? does it not naturally follow, that though almost the whole number of the inoculated recover, the disease must have been spread by their means, and a greater proportion having taken the natural disease, a consequent greater loss has been sustained by the public? If the above is admitted, it will be difficult to exculpate Inoculation from having been hurtful to society2.

Several attempts have been made to obviate this objection, many of which I have perused; but consistent with my intention of brevity, and avoiding all controversy, I shall decline entering into particulars, or inserting any quotations from authors. It will be sufficient to say, that although the arguments advanced have been ingenious, and in some respects just, they do not in my apprehension remove the objection that has been mentioned.

Let us see then whether the practice may not be fairly chargeable with some blame; and this will appear more evidently, if we take a view of the usual conduct of families on such occasions; which however pertinent to the question, seems hitherto to have been avoided, or not attended to, by the several writers on the subject.

In London it has been the general custom for those who intend to inoculate, to take into account all the circumstances that may be material for the conveniency of their families and friends, and these being settled to their minds, few precautions are thought necessary respecting the security of others: what passes previous to the eruptive fever, does not claim our consideration, since it is universally allowed that no infection can be communicated before that time; but it is after this period the danger begins, and the disease may be spread by the intercourse of visitants, trades people, washerwomen, servants, and others, and in a mild state of the disease, the frequent excursions of the sick by way of airings, and often in hired carriages of various kinds, contribute greatly towards spreading the infection. It would perhaps be deemed a designed omission, if the inoculators were not also supposed to be of the number of those that contribute to spread the disease.