полная версия

полная версияThe Turkish Empire, its Growth and Decay

A third cause, however, for the failure of the Ottomans to maintain their Empire in Europe is undoubtedly to be found in the continually worsening conditions of the Christian populations subject to it. In the earlier period there is good reason to conclude that the average condition of the rayas in the Christian provinces subjected to Ottoman rule and law was somewhat better than that of the peasants in some neighbouring States, such as Hungary, Austria, and Russia. There was something in the way of fixity of tenure accorded to the rayas which was absent from the feudal serfs.

It was alleged that peasants from Hungary not infrequently migrated into the Balkan States in order to enjoy this better treatment, and it is certain that the Greeks of the Morea and Crete preferred the rule of the Ottomans, bad as it was, to that of the Venetians, who were even more cruel and rapacious. However that may have been, it is certain that everywhere under Turkish rule, during the last three hundred years, the conditions of the Christian populations became more wretched and intolerable, and relatively far worse than in neighbouring States. This was greatly due to the degeneracy and corruption of the central Government at Constantinople, and to its evil example and influence throughout the Empire. Governors of provinces and all local officials became more corrupt and rapacious. There was no security for life or property. Justice was not obtainable in the local tribunals. Arbitrary exactions were levied on the peasantry. Brigandage everywhere increased. Money levied in the provinces was never expended for the benefit of their populations. Turkish rule acted as a blight on the districts subject to it. Provinces liberated from it improved in condition beyond recognition. The comparison with them was an ever present object-lesson to those who remained under Turkish rule. The efforts of the combined Powers of Europe to induce or compel the Porte to effect improvements in the government of its subjects proved to be futile and impotent. Treaty obligations with this object were habitually disregarded by the Porte and were treated as waste-paper. Provinces thus conditioned were always on the brink of rebellion. They were kept in subjection, not by the maintenance of any large armed forces there, but by periodic massacres of a ruthless character. These were not the product of religious fanaticism, as has often been suggested, but of deliberate policy, and were instigated by orders direct from the Porte, with the hope of inspiring terror in the minds of the subject races.

Foreign intervention, incited not so much by territorial ambition as by popular sympathy for the oppressed, was resorted to for the purpose of redressing grievous wrongs and for preserving the peace of Europe. As a result of these causes, extending over more than three hundred years, the Turkish Empire, so far as Europe is concerned, and in the sense of a dominant Power over subject races, has ceased to exist. In countries which it held in subjection for over five hundred years it has left no trace that it ever existed. The very few Turks and the Tartars and Circassians who had been planted there by the Porte when the Crimea and the Caucasus were subjected by Russia have departed bag and baggage from Europe. They have migrated to Asia Minor at the instigation of their mollahs. The few Moslems who remain behind in these districts are not of Ottoman or Turkish descent; they are of the same races as their neighbours. Their ancestors adopted Islam to save their property.

The Young Turks, who of late years have controlled the Empire, have signally failed to arrest the great movement which we have above described. They have further developed their policy of Turkifying what remains to them of the Empire during the existing war. Their massacres and deportations of Armenians in Asia Minor have been on a scale and with a cruelty without precedent in history. Whether responsibility for this indelible crime will be enforced on them, and whether, as it richly deserves, the Turkish Empire will suffer further reductions, will depend on the issue of the colossal struggle in which the nations of Europe are now engaged. Whatever the future may have in store in these respects, there is one certain moral to be drawn from the story which has been told in these pages, namely that an Empire originally founded on the predatory instincts of an alien military caste, and whose rulers during the last four hundred years have never recognized that they had any responsibility for the good government and well-being of the races subject to them, could not, if there be any law of human progress in the world, be permanent, and was destined ultimately to perish by the sword.

APPENDIX

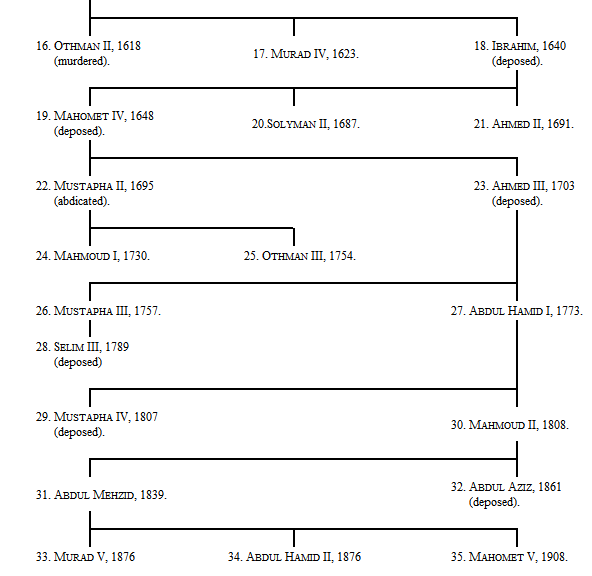

GENEALOGY OF THE OTTOMAN SULTANS

1

Von Hammer, i. p. 28 (French translation).

2

Cantemir, p. 20.

3

Mr. Gibbons refuses credence to this interesting story on the ground mainly of its inherent improbability. His argument does not convince me. The succession of the younger brother to the Emirate without a fight for it, on the part of the elder one, was an event so remarkable, and so contrary to all experience in Ottoman history, as to make the explanation given a reasonable one. The probabilities seem to me to be all in its favour. Alaeddin died in 1337. It is admitted that for seven years he acted as the first Grand Vizier of the Ottoman State. It may well be, therefore, that he commenced, if he did not complete, the important organization of the army with which he has been credited by Turkish historians.

4

This was not the corps of Janissaries, which, as Mr. Gibbons has shown, was created not by Orchan but by his son Murad.

5

Mr. Gibbons in his account of the origin of this corps disputes the figures as reported above from previous writers, and also the alleged motives for its constitution. After careful consideration of the question, I have preferred to adhere to the version given by Sir Edwin Pears, who has investigated the subject with great care in the early Greek and Turkish histories. I have, however, followed Mr. Gibbons in one point, namely, in attributing the constitution of the force to Murad I rather than to Orchan. Mr. Gibbons’s account of the corps of Janissaries is to be found on pp. 118-20 of the Foundation of the Ottoman Empire, and that of Sir Edwin Pears in his work on the Destruction of the Greek Empire, pp. 223-30.

6

Pears, p. 228.

7

Knolles, i. p. 139.

8

Gibbons, p. 221.

9

Froissart, xvi. 47.

10

Boucicaut in 1399, with four ships and two armed galleys and twelve hundred knights and foot soldiers, after defeating an Ottoman fleet in the Dardanelles, arrived at Constantinople and gave assistance to the Emperor in defence of the city.

11

Gibbon, viii. p. 114.

12

This story of the cage, which forms the subject of a scene in Marlowe’s play of Tamerlane, has been discredited by some historians of late years. But Mr. Gibbons, after a full and careful examination of all the records of the time, has re-established its veracity.

13

Gibbon, viii. p. 242.

14

Von Hammer, ii. p. 379.

15

Sir Edwin Pears, Destruction of the Greek Empire, p. 217.

16

The four pages which Gibbon devotes to a description of this attempted union of the two Churches are masterpieces of irony and scorn (Gibbon, viii. pp. 287-91).

17

The writer, in 1890, had the advantage of viewing what remained of these walls in the company of Sir Edwin Pears, who has fully described them in his admirable account of the great siege.

18

Stone balls of considerable size were used by the Turks to defend the Dardanelles up to a late date. When in 1855 the writer visited the forts there, he observed that they were still provided for some of the guns.

19

Speech of Mahomet recorded by the historian Christobulus, quoted by Sir Edwin Pears, pp. 323-4.

20

Quoted by Pears, p. 303.

21

Von Hammer, vii. p. 4.

22

Sir T. Roe’s Embassy, pp. 66-7.

23

Ibid. p. 178.

24

Ibid. p. 206.

25

Ibid. p. 243.

26

Von Hammer, xi. p. 378.

27

Schimmer, Two Sieges of Vienna, p. 137.

28

Von Hammer, xii. p. 372.

29

See the Mémoires de Morosini, iii. pp. 112, 113.

30

Whitworth to Leeds, January 10, 1781; Record Office.

31

Ranke’s History of Serbia, p. 115.

32

Moltke, p. 257.

33

Moltke, p. 443.

34

Finlay, vii. 59.

35

The above conversations are reported in Parliamentary Papers, 1854, Eastern Question, House of Commons, 84.

36

Life of Lord Stratford, ii. p. 442.

37

Life of Lord Stratford, ii. p. 436.

38

The above is from notes of conversations with Lord Stratford made at the time.

39

Life of Lord Stratford, ii. p. 449.

40

Lord Morley’s Life of Gladstone, ii. p. 555.

41

It may be well to add, what has not been mentioned by his able biographer, doubtless because Lord Stratford’s daughters were alive when the book was published in 1888, that the Great Elchi gave testimony of his belief in the permanence of the Turkish Empire by investing the greater part of his personal property and savings in Turkish Bonds. In 1874, when the Porte became bankrupt and repudiated payment of interest on the debt, some friend at Constantinople wrote to Lord Stratford giving timely information of what was coming and advising him to sell his bonds while there was yet time. Lord Stratford, however, thought it was inconsistent with his sense of honour to act on this advice. His means were greatly reduced by the bankruptcy of the Porte. After his death and the cessation of his pension, his daughters would have been in very reduced circumstances if it had not been for the generosity of a personal friend of their father, the late Lady Ossington, who made up to these ladies, for their lives, the amount of the pension from the State which had lapsed by the death of Lord Stratford.

42

The Bulgarian Horrors and the Question in the East, 1876.

43

House of Commons, April 24, 1877.

44

Bismarck induced Lord Beaconsfield to propose this to the Congress.

45

Parliamentary Report, House of Commons, July 30, 1878.

46

Nineteenth Century Review, December 1890. This article, which contained other severe criticisms on the rule of Abdul Hamid, was translated into the Turkish language, for his perusal, by the late Professor Arminius Vambéri, who was the guest of the Sultan at the time of my visit to Constantinople in 1890, and who had suggested to him that he should favour me with an audience. The Professor backed up my statements by remonstrances on his own behalf, with the result that the Sultan took grave offence. He withdrew the pension which he had annually paid to the Professor and put an end to their long friendship.

47

The Near East from Within, p. 38.

48

The Balkan Cockpit, G. M. Crawford Price, p. 102.