полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

Stage-coach and Tavern Days

By ancient common law and English law real property never ascended, that is, was never inherited by a father or mother from a child; but in absence of husband, wife, or lineal descendant passed on to the “next of kin,” which might be a distant cousin. By general interpretation the Province Laws substituted the so-called civilian method of counting kinship, by which the father could inherit.

Twice defeated in the courts, Dr. Ames boldly pushed his case in 1748 before the “Superior Court of Judicature, etc., of the Province of Massachusetts Bay,” himself preparing unaided both case and argument, and he triumphed. By the Province Laws he was given full possession of the property inherited by his infant child from the mother – thus the inn became Ames Tavern.

Nervous in temperament, excited by his victory, indignant at the injustice and loss to which he had been subjected; he was loudly intolerant of the law’s delay, and especially of the failure of Chief Justice Dudley and his associate Lynde, to unite with the three other judges, Saltonstall, Sewall, and Cushing, in the verdict; and in anger and derision he had painted for him and his tavern a new and famous sign, and he hung it in front of the tavern in caricature of the court.

The sign is gone long ago; but in that entertaining book, The Almanacks of Nathaniel Ames 1726-1775, the author, Sam Briggs, gives an illustration of the painting from a drawing found among Dr. Ames’ papers after his death, a copy of which is shown on the foregoing page. On the original sketch these words are written: —

“Sir: – I wish could have some talk on ye above subject, being the bearer waits for an answer shal only observe Mr Greenwood thinks yt can not be done under £40 Old Tenor.”

This was a good price to pay to lampoon the court, for the sign represented the whole court sitting in state in big wigs with an open book before them entitled Province Laws. The dissenting judges, Dudley and Lynde, were painted with their backs turned to the book. The court, hearing of the offending sign-board, sent the sheriff from Boston to bring it before them. Dr. Ames was in Boston at the time, heard of the order, rode with speed to Dedham in advance of the sheriff, removed the sign, and it is said had allowance of time sufficient to put up a board for the reception of the officer with this legend, “A wicked and adulterous generation seeketh after a sign, but there shall no sign be given it.”

The old road house, after this episode in its history, became more famous than ever before; and The Almanac was a convenient method of its advertisement, as it was of its distance from other taverns. In the issue of 1751 is this notice: —

“ADVERTISEMENT“These are to signify to all Persons that travel the great Post-Road South West from Boston That I keep a house of Public Entertainment Eleven Miles from Boston at the sign of the Sun. If they want Refreshment and see Cause to be my Guests, they shall be well entertained at a reasonable rate.

N. Ames.”Here lived the almanac-maker for fifteen years; here were born by a second wife his famous sons, Dr. Nathaniel Ames and Hon. Fisher Ames. Here in 1774 his successor in matrimony and tavern-keeping, one Richard Woodward, kept open house in September, 1774, for the famous Suffolk Convention, where was chosen the committee that drafted the first resolutions in favor of trying the issue with Great Britain with the sword. My great-grandfather was a member of this convention at Ames Tavern, and it has always seemed to me that this was the birthplace of the War for Independence. During the Revolution, as in the French and Indian War, the tavern doors swung open with constant excitement and interest. Washington, Lafayette, Hancock, Adams, and scores of other patriots sat and drank within its walls. It stood through another war, that of 1812, and in 1817 its historic walls were levelled in the dust.

The tavern sign-board was not necessarily or universally one of the elaborate emblems I have described. Often it was only a board painted legibly with the tavern name. It might be attached to a wooden arm projecting from the tavern or a post; it might be hung from a near-by tree. Often a wrought-iron arm, shaped like a fire crane, held the sign-board. The ponderous wooden sign of the Barre Hotel hung from a substantial frame erected on the green in front of the tavern. Two upright poles about twenty feet long were set five feet apart, with a weather-vane on top of each pole. A bar stretched from pole to pole and held the sign-board. A drawing of it from an old print is shown on page 280.

Rarely signs were hung from a beam stretched across the road on upright posts. It is said there are twenty-five such still remaining and now in use in England. A friend saw one at the village of Barley in Herts, the Fox and Hounds. The figures were cut out of plank and nailed to the cross-beam, the fox escaping into the thatch of the inn with hound in full cry and huntsmen following. Silhouetted against the sky, it showed well its inequality of outline. A similar sign of a livery stable in Baltimore shows a row of galloping horses.

Sometimes animals’ heads or skins were nailed on a board and used as a sign. Ox horns and deer horns were set over the door. The Buck Horn Tavern with its pair of branching buck horns is shown on the opposite page. This tavern stood on Broadway and Twenty-second Street, New York.

The proverb “Good wine needs no bush” refers to the ancient sign for a tavern, a green bush set on a pole or nailed to the tavern door. This was obsolete, even in colonial days; but in Western mining camps and towns in modern days this emblem has been used to point out the barroom or grocery whiskey barrel. The name “Green Bush” was never a favorite in America. There was a Green Bush Tavern in Barrington, Rhode Island, with a sign-board painted with a green tree.

CHAPTER VIII

THE TAVERN IN WAR

The tavern has ever played an important part in social, political, and military life, has helped to make history. From the earliest days when men gathered to talk over the terrors of Indian warfare; through the renewal of these fears in the French and Indian War; before and after the glories of Louisburg; and through all the anxious but steadfast years preceding and during the Revolution, these gatherings were held in the ordinaries or taverns. What a scene took place in the Brookfield tavern, the town being then called Quawbaug! The only ordinary, that of Goodman Ayers, was a garrison house as well as tavern, and the sturdy landlord was commander of the train-band. When the outbreak called King Philip’s War took place, things looked black for Quawbaug. Hostile and treacherous Indians set upon the little frontier settlement, and the frightened families retreated from their scarcely cleared farms to the tavern. Many of the men were killed and wounded at the beginning of the fray, but there were eighty-two persons, men, women, and children, shut up within the tavern walls, and soon there were four more, for two women gave birth to twins. The Indians, “like so many wild bulls,” says a witness, shot into the house, piled up hay and wood against the walls, and set it on fire. But the men sallied out and quenched the flames. The next night the savages renewed their attack.

“They used several stratagems to fire us, namely, by wild-fire on cotton and linen rags with brimstone in them, which rags they tied to the piles of their arrows sharp for the purpose and shot them to the roof of our house after they had set them on fire, which would have much endangered in the burning thereof, had we not used means by cutting holes through the roof and otherwise to beat the said arrows down, and God being pleased to prosper our endeavours therein.”

Again they piled hay and flax against the house and fired it; again the brave Englishmen went forth and put out the flames. Then the wily Indians loaded a cart with inflammable material and thrust it down the hill to the tavern. But the Lord sent a rain for the salvation of His people, and when all were exhausted with the smoke, the August heat, the fumes of brimstone, and the burning powder, relief came in a body of men from Groton and one brought by a brave young man who had made his way by stealth from the besieged tavern to Boston. Many of the old garrison houses of New England had, as taverns, a peaceful end of their days.

A centre of events, a centre of alarms, the tavern in many a large city saw the most thrilling acts in our Revolutionary struggle which took place off the battlefields. The tavern was the rendezvous for patriotic bands who listened to the stirring words of American rebels, and mixed dark treason to King George with every bowl of punch they drank. The story of our War for Independence could not be dissociated from the old taverns, they are a part of our national history; and those which still stand are among our most interesting Revolutionary relics.

John Adams left us a good contemporaneous picture of the first notes of dissatisfaction such as were heard in every tavern, in every town, in the years which were leading up to the Revolution. He wrote: —

“Within the course of the year, before the meeting of Congress in 1774, on a journey to some of our circuit courts in Massachusetts, I stopped one night at a tavern in Shrewsbury about forty miles from Boston, and as I was cold and wet, I sat down at a good fire in the bar-room to dry my great-coat and saddle-bags, till a fire could be made in my chamber. There presently came in, one after another, half a dozen, or half a score substantial yeomen of the neighborhood, who, sitting down to the fire after lighting their pipes, began a lively conversation on politics. As I believed I was unknown to all of them, I sat in total silence to hear them. One said, ‘The people of Boston are distracted.’ Another answered, ‘No wonder the people of Boston are distracted. Oppression will make wise men mad.’ A third said, ‘What would you say if a fellow should come to your house and tell you he was come to take a list of your cattle, that Parliament might tax you for them at so much a head? And how should you feel if he was to go and break open your barn or take down your oxen, cows, horses, and sheep?’ ‘What should I say?’ replied the first, ‘I would knock him in the head.’ ‘Well,’ said a fourth, ‘if Parliament can take away Mr. Hancock’s wharf and Mr. Rowe’s wharf, they can take away your barn and my house.’ After much more reasoning in this style, a fifth, who had as yet been silent, broke out: ‘Well, it’s high time for us to rebel; we must rebel some time or other, and we had better rebel now than at any time to come. If we put it off for ten or twenty years, and let them go on as they have begun, they will get a strong party among us, and plague us a great deal more than they can now.’”

These discussions soon brought decisions, and by 1768 the Sons of Liberty were organized and were holding their meetings, explaining conditions, and advocating union and action. They adopted the name given by Colonel Barré to the enemies of passive obedience in America. Soon scores of towns in the colonies had their liberty trees or liberty poles.

These patriots grew amazingly bold in proclaiming their dissatisfaction with the Crown and their allegiance to their new nation. The landlord of the tavern at York, Maine, speedily set up a sign-board bearing a portrait of Pitt and the words, “Entertainment for the Sons of Liberty.” Young women formed into companies called Daughters of Liberty, pledged to wear homespun and drink no tea. I have told the story of feminine revolt at length in my book Colonial Dames and Goodwives. John Adams glowed with enthusiasm when he heard two Worcester girls sing the “New Liberty Song,” in a Worcester tavern. In 1768 a Liberty Tree was dedicated in Providence, Rhode Island. It was a vast elm which stood in the dooryard of the Olney Tavern on Constitution Hill. On a platform built in its branches about twenty feet from the ground, stood the orator of the day, and in an eloquent discourse dedicated the tree to the cause of Liberty. In the trying years that followed, the wise fathers and young enthusiasts of Providence gathered under its branches for counsel. The most famous of these trees of patriotism was the Liberty Tree of Boston. It stood near a tavern of the same name at the junction of Essex and Washington streets, then known as Hanover Square. The name was given in 1765 at a patriotic celebration in honor of the expected repeal of the Stamp Act. Even before that time effigies of Lord Oliver and a boot for Lord Bute, placards and mottoes had hung from its branches. A metal plate was soon attached to it, bearing this legend, “This tree was planted in 1646 and pruned by order of the Sons of Liberty February 14, 1766.” Under the tree and at the tavern met all patriot bands, until the tree was cut down by the roistering British soldiers and supplied them with fourteen cords of firewood. The tavern stood till 1833. A picture of the Boston Liberty Tree and Tavern of the same name is shown on the opposite page. It is from an old drawing.

The fourteenth of August, 1769, was a merry day in Boston and vicinity. The Sons of Liberty, after assembling at the Liberty Tree in Boston, all adjourned for dinner at the Liberty Tree Tavern, or Robinson’s Tavern in Dorchester. Tables were spread in an adjoining field under a tent, and over three hundred people sat down to an abundant feast, which included three barbecued pigs. Speeches and songs inspired and livened the diners. The last toast given was, “Strong halters, firm blocks, and sharp axes to all such as deserve them.” At five o’clock the Boston Sons, headed by John Hancock in his chariot, started for home. Although fourteen toasts were given in Boston and forty-five in Dorchester, John Adams says in his Diary that “to the honor of the Sons I did not see one person intoxicated or near it.”

The tavern in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, known by the sign of Earl of Halifax, was regarded by Portsmouth patriots as a hotbed of Tories. It had always been the resort of Government officials; and in 1775, the meeting of these laced and ruffled gentlemen became most obnoxious to the Sons of Liberty, and soon a mob gathered in front of the tavern, and the irate landlord heard the blows of an axe cutting down his Earl of Halifax sign-post. Seizing an axe he thrust it into the hands of one of his powerful negro slaves, telling him to go and threaten the chopper of the sign-post. Excited by the riotous scene, the black man, without a word, at once dealt a powerful blow upon the head of a man named Noble, who was wielding the encroaching axe. Noble lived forty years after this blow, but never had his reason. This terrible assault of course enraged the mob, and a general assault was made on the tavern; windows and doors were broken; Landlord Stavers fled on horseback, and the terrified black man was found in a cistern in the tavern cellar, up to his chin in water. When Stavers returned, he was seized by the Committee of Safety and thrust into Exeter jail. He took the oath of allegiance and returned to his battered house. He would not reglaze the broken windows, but boarded them up, and it is said that many a distinguished group of officers feasted in rooms without a pane of glass in the windows.

Popular opinion was against the Earl of Halifax, however, and when the old sign-board was touched up, the name of William Pitt, the friend of America, appeared on the sign.

The portion of the old Earl of Halifax or Stavers Inn which is still standing is shown in its forlorn old age on the opposite page.

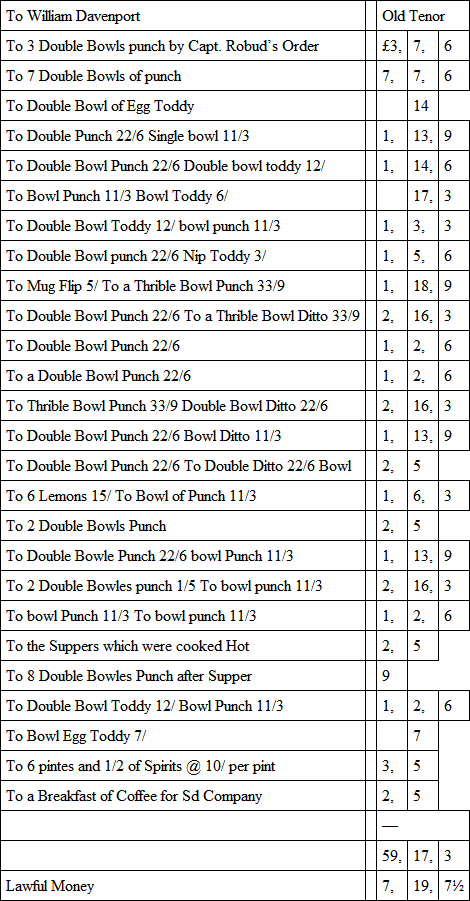

Mr. George Davenport, of Boston, a lineal descendant of old William Davenport, owns one of the most interesting tavern bills I have ever seen. It is of the old Wolfe Tavern at Newburyport. To those who can read between the lines it reveals means and methods which were calculated to arouse enthusiasm and create public sentiment during the exciting days of the Stamp Act. The bill and its items read thus: —

“Dr. Messrs. Joseph Stanwood & Others of the Town of Newburyport for Sunday expences at My House on Thirsday, Septr. 26th, A.D. 1765. At the Grate Uneasiness and Tumult on Occasion of the Stamp Act.

Newbury Port 28 Sept. 1765.

Errors excepted William Davenport.”

There was also a credit account of eleven pounds received in various sums from Captain Robud, Richard Farrow, and one Celeby.

It is impossible to do more than to name, almost at haphazard, a few of the taverns that had some share in scenes of Revolutionary struggle. Many served as court-rooms when court-martials were held; others were seized for military prisons; others were fired upon; others served as barracks; some as officers’ headquarters; others held secret meetings of patriots; many were used as hospitals.

Many an old tavern is still standing which saw these scenes in the Revolutionary War. A splendid group of these hale and hearty old veterans is found in the rural towns near Boston. At the Wright Tavern, in Concord (shown on page 417), lodged Major Pitcairn, the British commander, and in the parlor on the morning before the battle of Concord, he stirred his glass of brandy with his bloody finger, saying he would thus stir the rebel’s blood before night. The Monroe Tavern, of Lexington (facing page 406), was the headquarters of Lord Percy on the famous 19th of April, 1775. The Buckman Tavern, of the same town (page 23), was the rallying place of the Minute Men on April 18th, and contains many a bullet hole made by the shots of British soldiers. The Cooper Tavern (page 68) and the Russel Tavern (page 379), both of Arlington, were also scenes of activity and participation in the war. The Wayside Inn of Sudbury (page 372) and the Black Horse Tavern of Winchester were the scenes of the reassembling of the soldiers after the battle of Lexington.

On the south side of Faneuil Hall Square in Boston, a narrow passageway leads into the gloomy recesses of a yard or court of irregular shape; this is Corn Court, and in the middle of this court stands, overshadowed by tall modern neighbors, the oldest inn in Boston. It has been raised and added to, and disfigured with vast painted signs, and hideous fire escapes, but within still retains its taproom and ancient appearance. As early as 1634, Samuel Cole had an ordinary on this spot, and in 1636, Governor Vane entertained there Miantonomah and his twenty warriors. This building, built nearly two centuries ago, was given the name of Hancock in 1780, when he became governor. In 1794, Talleyrand was a guest at this old hostelry, and Louis Philippe in 1797. Washington, Franklin, and scores of other patriots have tarried within its walls; and in its taproom were held meetings of the historic Boston Tea-party.

The Green Dragon Inn was one of the most famous of historic taverns. A representation of it from an old print is shown on page 187. The metal dragon which gave the name projected from the wall on an iron rod.

Warren was the first Grand Master of the first Grand Lodge of Masons that held its meetings at this inn; and other patriots came to the inn to confer with him on the troublous times. The inn was a famous resort for the sturdy mechanics of the North End. Paul Revere wrote: —

“In the fall of 1774 and winter of 1775, I was one of upwards of thirty men, chiefly mechanics, who formed ourselves with a Committee for the purpose of watching the movements of the British soldiers and gaining every intelligence of the movements of the Tories. We held our meetings at the Green Dragon Tavern. This committee were astonished to find all their secrets known to General Gage, although every time they met every member swore not to reveal their transactions even to Hancock, Adams, Otis, Warren or Church.”

The latter, Dr. Church, proved to be the traitor. The mass meeting of these mechanics and their friends held in this inn when the question of the adoption of the Federal Constitution was being considered was deemed by Samuel Adams one of the most important factors of its acceptance. Daniel Webster styled the Green Dragon the Headquarters of the Revolution. During the war it was used as a hospital.

It is pleasant to note how many old taverns in New England, though no longer public hostelries, still are occupied by descendants of the original owners. Such is the home of Hon. John Winn in Burlington, Massachusetts. It stands on the road to Lowell by way of Woburn, about eleven miles out of Boston. The house was used at the time of the battle of Bunker Hill as a storage-place for the valuables of Boston and Charlestown families. The present home of the Winns was built in 1734 upon the exact site of the house built in 1640 by the first Edward Winn, the emigrant. In it the first white child was born in the town of Woburn, December 5, 1641.

The tavern was kept in Revolutionary days by Lieutenant Joseph Winn, who marched off to join the Lexington farmers on April 19, 1775, at two o’clock in the morning, when the alarm came “to every Middlesex village and farm” to gather against the redcoats. He came home late that night, and fought again at Bunker Hill.

The tavern sign bore the coat of arms of the Winns; it was – not to use strict heraldic terms – three spread eagles on a shield. As it was not painted with any too strict obedience to the rules of heraldry or art, nor was it hung in a community that had any very profound knowledge or reverence on either subject, the three noble birds soon received a comparatively degraded title, and the sign-board and tavern were known as the Three Broiled Chickens.

A building in New York which was owned by the De Lanceys before it became a public house is still standing on the southeast corner of Broad and Pearl streets; its name is well known to-day, Fraunces’ Tavern. This name came from the stewardship of Samuel Fraunces, “Black Sam,” a soldier of the American Revolution. The tavern originally bore a sign with the device of the head of Queen Charlotte, and was known as the Queen’s Head, but in Revolutionary times Black Sam was a patriot, and in his house were held many patriotic and public meetings. The most famous of these meetings, one which has given the name of Washington’s Headquarters to the tavern, was held in the Long Room on December 4, 1783: whereat Washington sadly bade farewell to his fellow-officers who had fought with him in the War for Independence. In this room, ten days previously, had been celebrated the evacuation of the city of New York by the British, by a dinner given to General Washington by Governor Clinton, at which the significant thirteen toasts were drunk to the new nation. Black Sam was a public benefactor as well as a patriot. He established a course of lectures on natural philosophy, and opened an exhibition of wax figures, seventy in all, for the amusement of New Yorkers. His story, and that of the tavern bearing his name, have been told at length many times in print.

Another interesting Revolutionary inn in New York was the Golden Hill Inn. The general estimate of the date of its building is 1694; then 122 William Street was a golden grainfield, on one corner of the Damon Farm. After three-quarters of a century of good hospitality it was chosen as the headquarters of the Sons of Liberty in New York, and within its walls gathered the committee in 1769, to protest against Lieutenant-governor Colden’s dictum that the colonists must pay for supplies for the British soldiers. The result was a call for a meeting of the citizens and the governor’s angry offer of a reward for knowledge of the place of meeting. The cutting down of the liberty pole on the night of January 17, 1770, and the seizure of four red-coats by the patriots ended in a fight in the inn garden and the death of one patriot. A century of stirring life followed until 1896, when the old tavern sadly closed its doors under the pressure of the Raines Law.

The Keeler Tavern was a famous hostelry for travellers between New York and Boston. Its old sign-board is shown on page 205. During the Revolution, landlord Keeler was well known to be a patriot, and was suspected of manufacturing cartridges in his tavern. The British poured a special fire upon the building, and one cannon ball lodged in a timber on the north side of the house still is to be seen by drawing aside the shingle that usually conceals it. A companion cannon ball whistled so close to a man who was climbing the stairs of the house that he tumbled down backward screaming, “I’m a dead man,” until his friends with difficulty silenced him, and assured him he was living. A son of the landlord, Jeremiah Keeler, enlisted in the Continental army when but seventeen; he became a sergeant, and was the first man to scale the English breastworks at Yorktown. He was presented with a sword by his commanding officer, Lafayette, and it is still preserved.