полная версия

полная версияMusical Myths and Facts, Volume 1 (of 2)

By making beautiful "mistakes," Beethoven has extended the rules of composition. Ries relates, "During a walk I took with him, I spoke to him of certain consecutive fifths which occur in his C minor Quartet, Op. 18, and which are so eminently beautiful. Beethoven was not aware of them, and maintained that I must be in error as to their being fifths. As he was in the habit of always carrying music paper with him, I asked for it, and wrote down the passage in all its four parts. When he saw that I was right, he said, 'Well, and who has forbidden them?' Not knowing how to take this question, I hesitated. He repeated it, until I replied in astonishment, 'But, they are against the first fundamental rules!' 'Who has forbidden them?' repeated Beethoven. 'Marpurg, Kirnberger, Fuchs, etc., etc. – all theorists,' I replied. 'And I permit them!' said Beethoven."

The harsh beginning of Mozart's C major Quartet (No. 6 of the set dedicated to Joseph Haydn) has been the subject of fierce attacks and controversies. Many musicians have supposed that misprints must have crept into the score; while others have endeavoured to prove in detail that all the four instruments are treated strictly according to the rules of counterpoint. Otto Jahn (in his 'Biography of Mozart,' Vol. IV. p. 74) finds it beautiful as "the afflicted and depressed spirit which struggles for deliverance." This may be so; and it is needless to conjecture what the admirers of the passage would have said, if it had emanated from an unknown composer. As it stands, it is, at any rate, interesting as an idea of Mozart, whose compositions are generally distinguished by great clearness of form and purity of harmony.

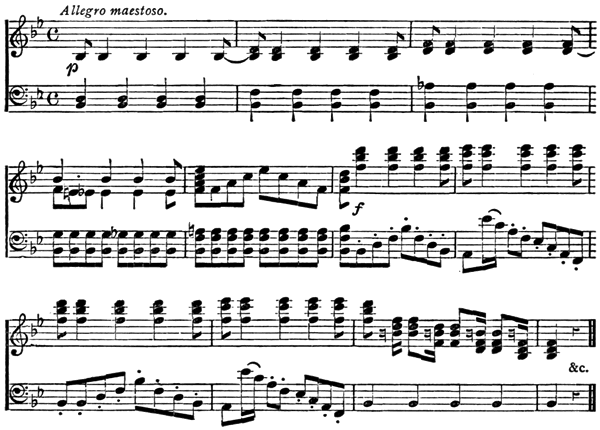

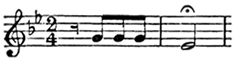

The adherence to a strictly prescribed form may easily lead the composer to the re-employment of some peculiar idea which he has already employed in a previous work. In fugues especially this may be often observed. Beethoven, in his sonatas, and likewise in his other compositions written in the sonata form, as trios, quartets, etc., introduces not unfrequently in the modulation from the tonic to the dominant certain favourite combinations of chords and modes of expression; and he has one or two phrases which may be recognised with more or less modification, in many of his compositions. Mozart, too, has his favourite successions of chords; for instance, the interrupted cadence which the German musicians call Trugschluss. Spohr repeats himself perhaps more frequently than any other composer. Mendelssohn has a certain mannerism in the rhythmical construction of many of his works, which gives them a strong family likeness. Weber has employed a certain favourite passage of his, constructed of groups of semi-quavers, so frequently, that the sight of a notation like this: —

is to the musician almost the same as the written name Carl Maria von Weber.

Some of the best examples for illustrating the studies of our great composers are to be found in those compositions which originally formed part of earlier and comparatively inferior works, and which were afterwards incorporated by the composers into their most renowned works. In thus adopting a piece which would otherwise probably have fallen into oblivion, the composer has generally submitted it to a careful revision; and it is instructive to compare the revision with the first conception. Gluck has used in his operas several pieces which he had originally written for earlier works, now but little known. For instance, the famous ballet of the Furies in his 'Orfeo,' is identical with the Finale in his 'Don Juan,' where the rake is hurled into the burning abyss; the overture to 'Armida' belonged originally to his Italian opera, 'Telemacco;' the wild dance of the infernal subjects of Hate, in 'Armida,' is the Allegro of the duel-scene in his 'Don Juan.'

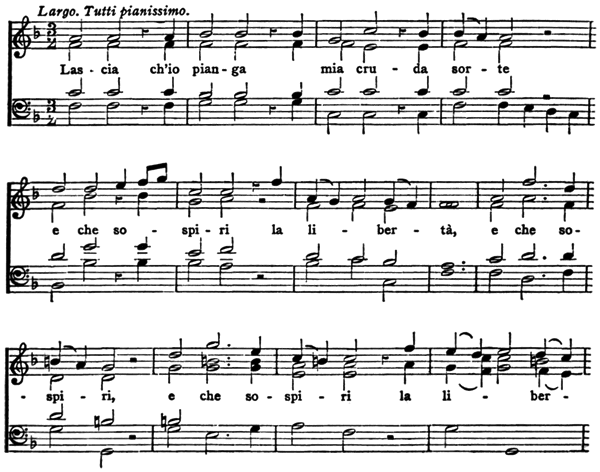

As an instance of adoption from a former work wonderfully improved by reconstruction, may be noticed Handel's Sarabande, in his opera 'Almira,' performed the first time at Hamburg in the year 1705: —

From this Sarabande, Handel, six years later, constructed the beautiful air "Lascia ch'io pianga," in his opera 'Rinaldo,' performed in London in the year 1711: —

Beethoven's third overture to his opera 'Leonora' (later called 'Fidelio') is a reconstruction of the second. A comparison of these two overtures affords an interesting insight into Beethoven's studies. It must be remembered that Beethoven, not satisfied with the first overture, wrote a second, and subsequently a third, and a fourth. The first three, which are in C major, he wrote when the opera was known by the name of 'Leonora;' and the fourth, which is in E major, when the opera was brought anew on the stage in its revised form under the name of 'Fidelio.' The air of Florestan is indicated in Nos. 1, 2, and 3, composed in 1805 and 1806. No. 2 has the distant trumpet-signal, produced on the stage; and in No. 3 this idea is further carried out; but in No. 4, written in 1814, it is dropped.

A composer who borrows from his former works deserves reproach as little as a person who removes his purse from one pocket into another which he thinks a better place. To borrow from the works of others, as some composers have done, is altogether a different thing. However, it would be unreasonable to regard such a plagiarism as a theft unless the plagiarist conceals the liberty he is taking by disguising the appropriation so as to make it appear a creation of his own. Some inferior musicians display much talent in this procedure. Our great composers, on the other hand, have often so wonderfully ennobled compositions of other musicians which they have thought advisable to admit into their oratorios, operas, or other elaborate works, that they have thereby honoured the original composers of those pieces as well as benefited art. It is a well-known fact that Handel has, in several of his oratorios, made use of the compositions of others. As these adoptions have been pointed out by one or two of Handel's biographers, it may suffice here to allude to them. Beethoven has adopted remarkably little. His employment of popular tunes where they are especially required, as for example in his Battle Symphony, Op. 91, can hardly be regarded as an instance to the contrary. At any rate, popular tunes have frequently been adopted by our great composers for the purpose of giving to a work a certain national character. Weber has done this very effectively in his 'Preciosa.' Gluck, in his 'Don Juan,' introduces the Spanish fandango. Mozart does the same in his 'Le Nozze di Figaro,' twenty-five years later. Here probably Mozart took a hint from Gluck. However this may be, there can be no doubt that Gluck's 'Don Juan' contains the germs of several beautiful phrases which occur in Mozart's 'Don Giovanni.' Even on this account it deserves to be better known to musicians than it is, independently of its intrinsic musical value. A detailed account of it here would, however, be a transgression. Suffice it to state that Gluck's 'Don Juan' is a ballet which was composed at Vienna in the year 1761, twenty-six years before Mozart produced his 'Don Giovanni.' The programme of the former work, which has been printed from a manuscript preserved in the Bibliothèque de l'Ecole Royale de Musique of Paris, shows that it is nearly identical with the scenarium of the latter work. The instrumental pieces, of which there are thirty-one, are mostly short, and increase in beauty and powerful expression towards the end of the work. The justly-deserved popularity in Vienna of Gluck's 'Don Juan' probably induced Mozart to have his 'Don Giovanni' first performed under the title of 'Il Dissoluto Punito,' and the great superiority of this opera may perhaps be the cause of Gluck's charming production having fallen into obscurity.

Mozart's facility of invention was so remarkably great that he can have had but little inducement to borrow from others. Plagiarisms occur but rarely in his works, but are on this account all the more interesting when they do occur. Take for instance the following passage from 'Ariadne of Naxos,' a duodrama by Georg Benda. It is composed to be played by the orchestra while Ariadne exclaims: "Now the sun arises! How glorious!"

Mozart was in his youth a great admirer of this duodrama. He mentions in one of his letters that he carried its score constantly with him. The great air of the Queen of Night in 'Die Zauberflöte,' Act 1, commences thus: —

It is, however, quite possible that Mozart had made Benda's work so thoroughly his own that he borrowed from it in the present instance without being aware of the fact.

Again, Johann Heinrich Rolle published in the year 1779 an oratorio entitled 'Lazarus, oder die Feier der Auferstehung' (Lazarus, or the Celebration of the Resurrection). The second part of this oratorio begins with an introductory symphony, as follows: —

Perhaps Mozart was not acquainted with Rolle's oratorio when he wrote his overture to the 'Zauberflöte,' in the year 1791. The curious resemblance in the two compositions may be entirely owing to the form of the fugue in which they are written.

Moreover, the theme of Mozart's overture to the 'Zauberflöte' resembles also the theme of a Sonata by Clementi which was composed ten years earlier than the overture. In Clementi's Sonata it is as follows: —

In the complete edition of Clementi's pianoforte compositions this Sonata is published with the appended notice that Clementi played it to the Emperor Joseph II. when Mozart was present, in the year 1781. Mozart appears to have been fond of the theme, for he introduces a reminiscence of it into the first movement of his Symphony in D major, dating from the year 1786.

The first chorus in Mozart's 'Requiem' was evidently suggested by the first chorus in Handel's 'Funeral Anthem for Queen Caroline.' The motivo of both is however an old German dirge dating from the sixteenth century, which begins thus: —

and which may have been familiar to Mozart as well as to Handel.

The motivo of the Kyrie Eleison in Mozart's 'Requiem:' —

occurs also in Handel's oratorio 'Joseph:' —

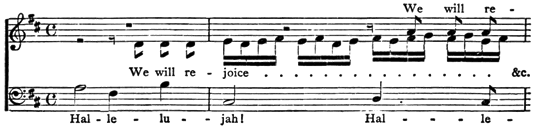

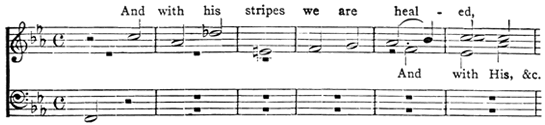

and in Handel's 'Messiah:' —

Likewise in a Quartet for stringed instruments by Haydn, Op. 20, thus: —

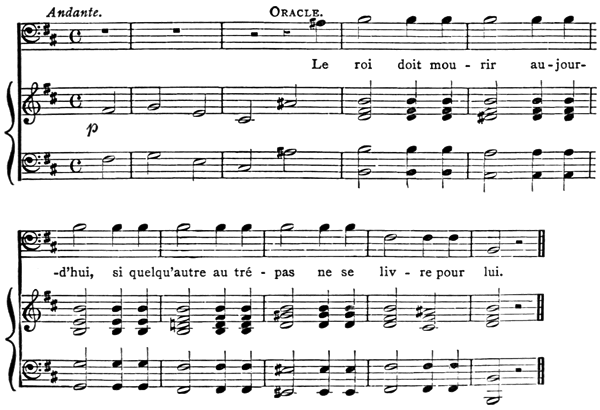

In the solemn phrase of the Commendatore, in 'Don Giovanni,' we have an interesting example of the happy result with which Mozart has carried out ideas emanating from Gluck. In the opera 'Alceste,' by Gluck, the Oracle sings in one tone, while the orchestral accompaniment, including three trombones, changes the harmony in each successive bar, as follows: —

That Mozart was much impressed with the effect of Gluck's idea may be gathered from the circumstance of his having adopted it in 'Don Giovanni,' and likewise, to some extent, in 'Idomeneo.' The Commendatore in 'Don Giovanni' sings, accompanied by trombones: —

There can hardly be a greater difference in the styles of two composers than exists in the style of Gluck and that of J. S. Bach. The masterly command of Bach over the combination of different parts according to the rules of counterpoint is just the faculty in which Gluck is deficient. It is on this account especially interesting to observe how Gluck has employed an idea which he apparently borrowed from Bach. The student may ascertain it by carefully comparing the air, 'Je l'implore, et je tremble,' in 'Iphigenia in Tauris,' with J. S. Bach's beautiful gigue in B flat major, commencing: —

Clementi, a pianoforte composer, who has certainly but little in common with Gluck, has for his B minor Sonata dedicated to Cherubini – perhaps his best work – a theme which may be recognised as that of the dance of the Scythians in 'Iphigenia in Tauris.'

Again, Beethoven's style, especially in his later works, is as different from Haydn's as possible; nevertheless we occasionally meet with a phrase in Beethoven's later works which appears to have been suggested by Haydn. For instance, Haydn, in his Symphony in B flat major (No. 2 of Salomon's set) has a playful repetition of a figure of semi-quavers leading to the re-introduction of the theme, thus: —

In Beethoven's famous E minor Quartet, Op. 59, a similar figure leads to the theme, thus: —

A more exact comparison of the two passages than the present short notations permit will probably convince the student of the great superiority of Beethoven's conception. He was one of those rare masters who convert into gold whatever they touch.

But it is not the object here to give a list of the similarities and adaptations which are traceable in the works of different musical composers. Such a list would fill a volume, even if composers of secondary rank, who are often great borrowers, were ignored. For the present essay a few examples must suffice, especially as others will probably occur to the reflecting reader.

Some insight into the studies of our great composers may also be obtained by comparing together such of their operas or other elaborate vocal compositions with instrumental accompaniment as are founded on the same subject. Note, for instance, the love-story of Armida, taken by the compilers of the various librettos from the episode of Rinaldo and Armida in Tasso's 'Gerusalemme Liberata.' The story had evidently a great attraction for the musical composers of the eighteenth century. There have been above thirty operas written on it, several of which it might now be difficult to procure, nor would an examination of them perhaps repay the trouble. However, the operas on the subject composed by Lulli, Gluck, Graun, Handel, Traetta, Jomelli, Naumann, Haydn, Sarti, Cimarosa, Rossini, Sacchini, etc., would suffice for the purpose. Thus also, a comparison of several compositions depicting a storm – most of our masters have written such a piece – elicits valuable hints for the musical student. Compare, for instance, with each other the storms in Gluck's 'Iphigenia in Tauris,' Haydn's 'Seasons,' Beethoven's 'Sinfonia Pastorale,' Cherubini's 'Medea.'

Even arrangements may illustrate the studies. Take, for instance, the arrangements of Vivaldi's violin concertos by J. S. Bach. It is, however, but seldom that eminent composers have occupied themselves with arranging the works of others. Instructive examples of this kind are therefore rare.

It is recorded of some composers that they were in the habit of founding their instrumental works on certain poetical ideas. Haydn is said to have done this almost invariably. Schindler, in his biographical notices of Beethoven, states that the two pianoforte Sonatas, Op. 14, of Beethoven, were explained to him by the composer as representing a dialogue between two lovers. When Schindler asked the meaning of the motivo of the C minor Symphony,

Beethoven exclaimed, "Thus Fate knocks at the gate!" And being requested by Schindler to supply him with the key to the Sonatas in D minor, Op. 31, and in F minor, Op. 57, Beethoven's answer was: "Read Shakespeare's 'Tempest!'" Beethoven probably resorted to such replies merely to satisfy troublesome inquirers somewhat resembling the inquisitive gentleman in Washington Irving's 'Tales of a Traveller,' who "never could enjoy the kernel of the nut, but pestered himself to get more out of the shell." Several of the titles of Beethoven's instrumental compositions ('Pastoral Sonata,' 'Moonlight Sonata,' 'Sonata appassionata,' etc.) did not originate with the composer, but were given to the pieces by the publishers to render them more attractive to the public. The title of his sonata Op. 81, 'Les Adieux, l'Absence et le Retour,' emanates however from Beethoven himself. This is noteworthy inasmuch as it has brought the advocates of descriptive music into an awkward dilemma. They found in this sonata an unmistakable representation of the parting and ultimate reunion of two ardent lovers, – when, unhappily for them, Beethoven's autograph manuscript of the sonata was discovered, in the library of Archduke Rudolph, bearing the inscription (in German), "The Farewell, Absence, and Return of His Imperial Highness the Venerated Archduke Rudolph."

A similar subject is treated by J. S. Bach, in a capriccio for the harpsichord, entitled, 'On the Departure of a very dear Brother,' in which the different movements are headed as follows: – "No. 1. Entreaty of friends to put off the journey. – No. 2. Representation of the various accidents which might befall him. – No. 3. General lament of friends. – No. 4. Entreaty being of no avail, the friends here bid farewell. – No. 5. Air of the postillion. – No. 6. Fuga in imitation of the post-horn."

This is but a modest essay in tone-painting compared with a certain production by Johann Kuhnau, a predecessor of Bach, who depicted entire biblical stories in a set of six sonatas for the clavichord, which were published in Leipzig in the year 1700. Each sonata is prefaced by a programme, which informs the player what is meant by the several movements – a very necessary proceeding. The stories depicted are from the Old Testament. One of the sonatas is entitled, 'Jacob's Marriage;' another, 'Saul cured by David's Music;' another, 'The Death of Jacob;' and so on. To show how far Kuhnau ventures into detailed description, the explanation printed with the sonata called 'Gideon' may find a place here. It runs as follows: – "1. Gideon mistrusts the promises made to him by God that he should be victorious. – 2. His fear at the sight of the great host of the enemy. – 3. His increasing courage at the relation of the dream of the enemy, and of its interpretation. – 4. The martial sound of the trombones and trumpets, and likewise the breaking of the pitchers and the cry of the people. – 5. The flight of the enemy and their pursuit by the Israelites. – 6. The rejoicing of the Israelites for their remarkable victory."

Still earlier, in the seventeenth century, Dieterich Buxtehude depicted in seven suites for the clavichord, 'The Nature and Qualities of the Planets;' and Johann Jacob Frohberger, about the same time, composed for the harpsichord a 'Plainte, faite à Londres, pour passer la mélancolie,' in which he describes his eventful journey from Germany to England – how in France he was attacked by robbers, and how afterwards in the Channel, between Calais and Dover, he was plundered by Tunisian pirates. Frohberger composed also an allemande intended to commemorate an event which he experienced on the Rhine. The notation is so contrived as to represent a bridge over the Rhine. Mattheson is said to have cleverly introduced into one of his scores, by means of the notation, the figure of a rainbow. Such music one must not hear; enough if one sees it in print. It deserves to be classed with the silent music mentioned in Shakespeare's 'Othello,' Act III., Scene 1: —

"Clown.– But, masters, here's money for you: and the General so likes your music, that he desires you, for love's sake, to make no more noise with it.

"First Musician.– Well, sir, we will not.

"Clown.– If you have any music that may not be heard, to't again: but, as they say, to hear music the General does not greatly care.

"First Musician.– We have none such, sir.

"Clown.– Then put your pipes in your bag, for I'll away: go, vanish into air; away!"

It may afford satisfaction to the lover of descriptive music to imagine he hears in certain choruses by Handel the leaping of frogs, the humming of flies, or the rattling of hailstones; but the judicious admirer of these compositions values them especially on account of their purely musical beauties. These may in a great measure be traced to euphony combined with originality. Music must be above all things melodiously beautiful. Our great composers bore this in mind, or acted upon it as a matter of course; hence the fascinating charms of their music. The euphony does not depend upon the consonant harmony prevailing in the composition; if this were the case, music would be the more euphonious the fewer dissonant chords it contains, and the major key would be more suitable for euphony than the minor key, since the major scale is founded upon the most simple relation of musical intervals yielding concords. However, our finest compositions contain numerous dissonant chords; and many – perhaps most – are in the minor key. Some of our great composers have certainly written more important works in minor than in major keys. Mozart, in those of his compositions which are in major keys, often manifests extraordinary inspiration as soon as he modulates into a minor key.

Remarkably devoid of euphony are the compositions of some musicians who, having taken Beethoven's last works as the chief models for their aspirations, have thereby been prevented from properly cultivating whatever gift they may naturally possess for expressing their ideas melodiously and clearly. Moreover, they talk and act as if affected originality, or far-fetched fancies, constituted the principal charm of a composition. Not less tedious are the works of some modern composers who possess no originality, but who write very correctly in the style of some classical composer. There has been published a vast amount of such stale and unprofitable productions. Music, to be interesting, must possess some quality in a high degree. If it is very good, it is just what it ought to be; if it is very bad, one can honestly condemn it, and leave it to its fate. But music which is neither very good nor very bad – which deserves neither praise nor blame, and which one cannot easily ignore because it is well meant – this is the most wearisome. And often how long such productions are! The composers show with many notes that they have felt but little, while our great composers show with but few notes that they have felt much.