полная версия

полная версияMusical Myths and Facts, Volume 2 (of 2)

The Half-Minor Scale contains the Minor Third, while its other intervals are identical with those of the Major Scale. This is the case in descending, where the seventh and sixth are lowered, as well as in ascending.

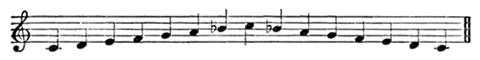

Furthermore, we have the Chromatic Scale, a regular progression in semitones, which is much used by modern composers; and the Enharmonic Scale, which may be said to exist only in notation, since it is not executable on most of our musical instruments, but which is likely to become important in the music of a future period when our instruments have been brought to the degree of perfection which permits the most delicate modifications in pitch by the performer, and which is at present almost alone obtainable on instruments of the violin kind.

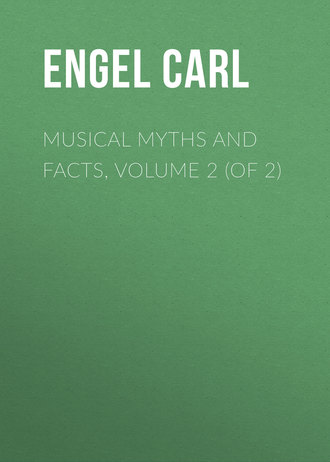

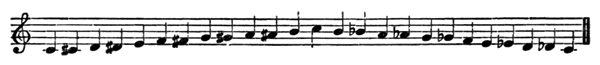

5. THE CHROMATIC SCALE

Furthermore, we find at the present day the following scales in use among foreign nations: —

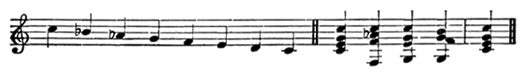

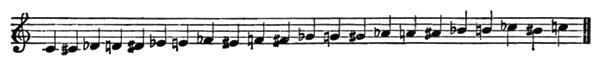

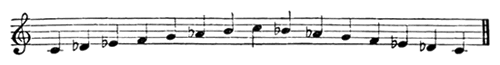

7. THE MINOR SCALE WITH TWO SUPERFLUOUS SECONDS

If the lover of music is acquainted with the popular songs and dance-tunes of the Wallachians, or with the wild and plaintive airs played by the gipsy bands in Hungary, he need not be told that the Minor Scale with two Superfluous Seconds is capable of producing melodies extremely beautiful and impressive. Indeed, it would be impossible to point out more charming and stirring effects than those which characterise the music founded on this scale.

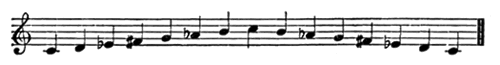

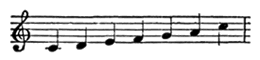

8. THE PENTATONIC SCALE

The Pentatonic Scale was in ancient times apparently more universally in use than it is at present. It is still popular in China, in Malaysia, and in some other Eastern districts. Traces of it are found in the popular tunes of some European nations, especially in those of the Celtic races. Its charming effect is known to most of our musicians through some of the Scotch and Irish melodies. Also among the Javanese tunes, which have been brought to Europe by travellers, and which are generally strictly pentatonic, some specimens are very melodious and impressive.

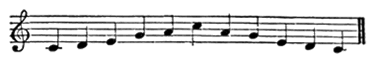

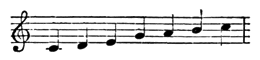

9. THE DIATONIC SCALE WITH MINOR SEVENTH

The Diatonic Scale with Minor Seventh is likewise an Eastern scale. Among European nations, the Servians especially have popular tunes which are founded on this scale. The Servian tunes frequently end with the interval of the Fifth instead of the First or the Octave. As the leading tone of our diatonic order of intervals – the Major Seventh – is wanting, our common cadence, or the usual harmonious treatment of the conclusion of a melody to which our ear has become so much accustomed that any other appears often unsatisfactory, cannot be applied to those tunes. Nevertheless, they will be found beautiful by inquirers who are able to dismiss prejudice and to enter into the spirit of the music. Although the scale with Minor Seventh bears a strong resemblance to one of our antiquated Church Modes, called Myxo-Lydian, it is in some respects of a very different stamp, since its characteristic features would become veiled if it were harmonised like that Church Mode.

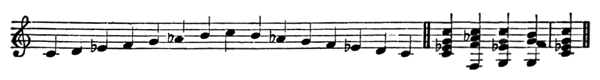

In addition to the nine scales which have been enumerated, some others could be pointed out which are popular in European countries; but, as they resemble more or less those which have been given above, and as they may be regarded as modifications, it will suffice here to refer to them only briefly. There are, for instance, in the Irish tunes many of a pentatonic character in which one of the two semitones of the diatonic scale is extant, and the scale of which therefore consists of six intervals, either thus

We also meet with a pentatonic order of intervals in which the Third is flat like in our diatonic minor scale.

Again, some nations which have the diatonic order of intervals deviate slightly from it by habitually intoning some particular interval in a higher or lower pitch than it occurs in our tempered system. For instance, careful observers have noticed that the Swiss peasants in singing their popular airs are naturally inclined to intone the interval of the Fourth sharper than it sounds on the pianoforte. Thus, in C-major it is raised so as to give almost the impression of F sharp. This peculiarity is supposed to have arisen from the Alphorn, a favourite instrument of the Swiss, on which the interval of the Fourth, like on a trumpet, is higher than it is in our Diatonic Scale. No doubt many peculiarities of this kind are traceable to the construction of certain popular instruments. This is perhaps more frequently observable among uncivilized nations than with Europeans. Professor Lichtenstein, who, during his travels in South Africa, in the beginning of the present century, investigated the music of the Hottentots, asserts that these people sing the interval of the Third slightly lower than the Major Third, but not so low as the Minor Third; and the Fifth and Minor Seventh likewise lower than in our intonation. He found that the same deviations from our intervals exist on the Gorah, a favourite stringed instrument of the Hottentots.

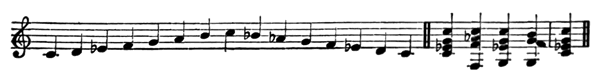

Other peculiarities of the kind are more difficult to explain. In the Italian popular songs of the peasantry, for instance, we not unfrequently meet with the Minor Second, where to an ear accustomed to our Minor Scale it appears like a whimsical substitution for the Major Second. It occurs, however, only occasionally. When it is used, the scale is as follows; the Seventh being Major in ascending, and Minor in descending: —

In some instances such peculiarities have evidently been derived, as has already been stated, from the series of tones produced on a popular instrument. But there are many instances in which the tones yielded by the instrument have been purposely adopted in the construction of the instrument from the previously existing popular scale of the vocal music. Thus, it may possibly be that, as some inquirers maintain, the pentatonic character of certain Irish airs has its origin in the primitive scale of the ancient rural bagpipe of Celtic races, or, as others believe, in the simple construction of the ancient Irish harp; – on the other hand, the Chinese and Javanese, as we have seen, contrive in the construction of their instruments to obtain the pentatonic scale on which their vocal music is usually founded.

Those theorists who regard our diatonic major scale as the most perfect one, which ultimately must be universally accepted as the only true one, will probably not admit that under certain circumstances the sounding of one or other of its intervals a little "out of tune" may actually increase the beauty of a musical performance. Such is, however, unquestionably the case. To note a curious instance in proof of the correctness of this assertion as afforded by the clavichord, a contemporary of the harpsichord and predecessor of the pianoforte: – The strings of the clavichord are not sounded by being twanged with quills, as is the case in the harpsichord, but are vibrated by means of iron pins, called tangents, which press under the strings when the keys are struck. The pressure of the tangent lasts as long as the key to which the tangent is attached is held down. The deeper the performer presses the key down with his finger, the stronger is the pressure of the tangent against the string, and the more the string is raised by it. The raising of the string has the effect of slightly raising the pitch of its tone. The performer, therefore, has it in his power to modify in some degree the pitch of a tone, and by this means to distinguish any tone to which he desires to give emphasis, or to render prominent in expressing a melody, or in executing a passage with delicacy. The aptness of the clavichord for yielding to these deviations from the intonation of the intervals in which it is tuned, combined with its aptness for producing with great delicacy different degrees of loudness, constitute the principal charms of the instrument, and sufficiently account for the love which our old classical composers, – Handel, Bach, etc., – bore for the clavichord.

A musical instrument containing all conceivable perfections for performance, we do not yet possess. Such an instrument would be required to yield not only Whole-Tones and Semitones, but likewise Demi-semitones, Semidemi-semitones, – in short, every modification of an interval which the performer desires. It must have the greatest compass obtainable in tones. All its tones must be of equal power, sonorousness and beauty. The sustaining, the increasing and decreasing in loudness, must be possible with each tone separately, at the option of the performer, even in harmonious combinations. Likewise the difference in manner of expression, such as legato, staccato, etc., must be thus obtainable. The greatest possible difference in the quality of sound (timbre) must be at the command of the performer for any tone which he wishes to be thus affected. The instrument must permit the simultaneous sounding of as many of its tones as the performer desires, whatever their distance from each other may be, and this must be achievable by him with about the same facility as he requires for the production of a single tone. The instrument must be playable by only one performer; it must not present any extraordinary difficulty to musicians to play it well; and it must permit being easily kept in tune. Perhaps the organ approaches the nearest to this perfection, but is still far from it. The violin and the violoncello are in some respects ahead of all – at any rate, as regards delicacy of expression.

But, fascinating though it may be to depict such a nearly perfect musical instrument of the Future, the real substitutes of our present contrivances, a century or two hence, will probably be very different from our ideal, especially if we found our speculation on the impression that our Tonal System is the only right one, and that our diatonic major scale will be as everlasting as a mathematical truth, or as the axiom that two and two are four.

Indeed, the mutability of the musical taste of man appears to be unlimited, and it is certainly possible that our children's children may find decidedly objectionable some rule of musical composition which is now thought highly satisfactory. Did not our ancestors at the time of Hucbald relish consecutive Fifths and Octaves as an harmonious accompaniment to a melody? A Chinese Mandarin, on hearing a French Jesuit, at Pekin, play on a clavecin some Suites de Pièces of a celebrated French composer, endeavoured to convince the performer that the Chinese music was the only true music "because," he said, "it appeals to the heart, while yours makes only noise." When Villoteau, during his residence in Egypt, investigated the Arabic music, his Arab music-master at Cairo endeavoured to convince him that the division of the Octave into seventeen intervals was more natural and tasteful than the European division into twelve chromatic intervals. A Nubian musician, on hearing Mr. Lane play the pianoforte, remarked: "Your instrument is very much out of tune, and jumps very much." He evidently missed the accustomed small intervals connecting the whole-tones in his own music. Livingstone, in his 'Missionary Travels in South Africa,' relates that on a certain occasion when an English missionary sang a hymn to an assembly of Bechuana Kafirs, "the effect on the risible faculties of the audience was such that the tears actually ran down their cheeks;" and the same may have happened to the missionary when he heard the Kafirs sing.

Many more examples from nations in different stages of civilization could be cited evidencing the remarkable variety and instability of musical taste. Much of our own music, which about a century ago was greatly admired, appears now unimpressive; and great masters who introduce important innovations are sure at first not to be understood by the majority of musical people.

Instead of regarding our Tonal System as exhibiting the highest degree of perfection attainable, and of repudiating musical conceptions which reveal another foundation, as our musicians are apt to do, it would be more wise in them to study the various systems on which the music of different nations is founded, to acquaint themselves especially with the characteristics of the various scales, and, by adopting them on proper occasions, to produce new effects more refreshing than the hackneyed phrases and modulations which usually pervade their works.

FINIS1

Vol. I., p. 94.

2

Hawkins's 'History of Music,' Vol. V., p. 253.

3

Halle.

4

Should be 1685.

5

That Handel was born on the 23rd of February, 1685, and not on the 24th of February, 1684, is correctly stated in J. J. Walther's 'Musicalisches Lexicon,' Leipzig, 1732. To settle the uncertainty about the date, which appears to have arisen chiefly through Mainwaring's mis-statement, J. J. Eschenburg consulted the Baptismal Register of the Frauenkirche in Halle, where he found the year 1685 given. (See 'Dr. Karl Burney's Nachricht von Georg Friedrich Handel's Lebens umständen, und der ihm zu London im May und Juny, 1784, angestellten Gedächtnissfeyer, aus den Englischen übersetzt von J. J. Eschenburg; Berlin, 1785'). – Förstemann ('Händel's Stammbaum,' Leipzig, 1844), and others, have subsequently convinced themselves that Eschenburg's date is correct. The year 1684, given on Handel's Monument in Westminster Abbey, therefore, requires rectifying.

6

Chrysander ('G. F. Handel,' Leipzig, 1858, Vol. I., p. 52) surmises that Handel was not in Berlin in 1698, but in 1696, when he was eleven years old.

7

This is a mis-statement. Handel, born in 1685, was 18 years old; and Mattheson, born in 1681, was 22 years old.

8

Wych?

9

Keiser.

10

Mattheson.

11

He was not quite twenty years old.

12

See the note above, page 11.

13

Mainwaring had probably obtained some of his information from Handel himself; but he may have forgotten the dates, or Handel may not have remembered them exactly.

14

Handel was 74 years old when he died.

15

Mattheson is mistaken here. It has been satisfactorily ascertained that Handel left Hamburg for Italy in the year 1706. (See G. F. Händel, von F. Chrysander, Leipzig, 1858, Vol. I., p. 139.)

16

The following well-authenticated data may serve to correct the "corrections" of Mattheson: – Handel was born in 1685; went to Hamburg in 1703; thence to Italy in 1706; from Italy to Hanover in 1710; thence to London in 1710; back to Hanover in 1711; returned to England in 1712, where he died in 1759.

17

Two works by Mattheson.

18

Page 4.

19

Page 7.

20

'Sagen, Gebräuche, und Märchen aus Westfahlen, gesammelt von A. Kuhn. Leipzig, 1859.' Vol. I., p. 175.

21

'Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland, by T. Crofton Croker; London, 1862,' p. 22. – Compare also 'Hans mein Igel,' in Grimm's Kinder und Hausmärchen.

22

'Deutsche Sagen, herausgegeben von den Brüdern Grimm; Berlin, 1816;' Vol. I., p. 330.

23

'Niederländische Sagen, herausgegeben von J. W. Wolf; Leipzig, 1843;' p. 464.

24

'Tonkünstler-Lexicon Berlin's, von C. Freiherrn von Ledebur;' Berlin, 1861; p. 6.

25

'Biographie von Ludwig van Beethoven, verfasst von A. Schindler;' Münster, 1845; p. 141.

27

'Biographische Notizen über L. van Beethoven, von Wegeler und Ries;' Coblenz, 1838; p. 34.

28

'Historisch-Kritische Beiträge zur Aufnahme der Musik, von F. W. Marpurg.' Vol. II., Berlin, 1756; p. 575.

29

'Franz Schubert, von H. Kreiszle von Hellborn;' Wien, 1865, p. 272.

30

£8.

31

'Franz Schubert, von H. Kreiszle von Hellborn;' Wien, 1865; p. 388.

32

Op. 114.

33

£6.

34

'Franz Schubert, von H. Kreiszle von Hellborn;' Wien, 1865; p. 442.

35

'Biographie W. A. Mozart's, von G. N. von Nissen;' Leipzig, 1828, p. 584.

36

See above, page 23.

37

Barbaja, the Impressario of the San Carlo Theatre at Naples.

38

'Aus dem Tonleben unserer Zeit, von Ferdinand Hiller; Leipzig, 1868.' Vol. II., p. 22.

39

'Jahrbücher für Musikalische Wissenschaft, herausgegeben von F. Chrysander.' Leipzig, 1863, p. 434.

40

See above, p. 45.

41

'Music and Friends, by William Gardiner.' Vol. III., London, 1853, p. 378.

42

'Carl Maria von Weber, ein Lebensbild,' von Max C. M. von Weber; Leipzig, 1864. Vol. II., p. 270.

43

'Illustrations of the Manners, Customs and Condition of the North American Indians, by G. Catlin.' London, 1848; Volume I., p. 40.

44

'Four Years in British Columbia and Vancouver Island, by R. C. Mayne.' London, 1862; p. 261.

45

'Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition during the years 1838-42, by Charles Wilkes.' London, 1845; Vol. IV., p. 399.

46

'Missionary Labours in British Guiana,' by the Rev. J. H. Bernau; London, 1847. p. 55.

47

'Two Thousand Miles' Ride through the Argentine Provinces,' by William MacCann; London, 1853. Vol. I., p. 111.

48

Machi is evidently identical with Manchi.

49

'The Geographical, Natural, and Civic History of Chili,' by the Abbé Don J. Ignatius Molina; London, 1809. Vol. II., p. 105.

50

'The Araucanians,' by E. R. Smith; London, 1855; p. 235.

51

'A Description of Patagonia and the adjoining parts of South America,' by Thomas Faulkner; Hereford, 1774; p. 115.

52

'Journal of a Residence among the Negroes in the West Indies,' by M. G. Lewis; London, 1845; p. 158.

53

The word Obeah is probably identical with Piaie, mentioned above, page 89.

54

'History of Loango,' by the Abbé Proyard; Paris, 1776. 'A General Collection of Voyages and Travels,' by John Pinkerton; London, 1808; Vol. XIV., p. 572.

55

'Reisen in Süd-Africa,' von Ladislaus Magyar; Pest, 1859; Vol. I., p. 26.

56

'The Kafirs of Natal and the Zulu Country,' by J. Shooter; London, 1857; p. 173.

57

'Outlines of a Grammar, Vocabulary, and Phraseology of the Aboriginal Language of South Australia.' By G. C. Teichelmann and C. W. Schürmann. Adelaide, 1840; part II.

58

'An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Islands.' By John Hunter. London, 1793; p. 476.

59

'Nineteen Years in Polynesia.' By the Rev. G. Turner. London, 1861.

60

Dried dung, which constitutes the chief, and indeed in many places the sole fuel in Tartary, is called argols.

61

'Travels in Tartary, Thibet, and China, during the years 1844-46,' by M. Huc; Vol. I., p. 76.

62

'Travels in South-eastern Asia,' by H. Malcom; Boston, 1839; Vol. II., p. 197.

63

'Six Months in British Burmah,' by C. F. Winter; London, 1858; p. 161.

64

'Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung;' Leipzig, 1841, No. 17.

65

'Travels and Observations relating to Barbary,' by Thomas Shaw. 'A General Collection of Voyages and Travels,' by J. Pinkerton; London, 1808; Vol. XV., p. 635.

66

'A Voyage to Abyssinia, etc.' By Henry Salt. London, 1814; p. 33.

67

'Griechische und Albanische Märchen, gesammelt von J. G. v. Hahn.' Leipzig, 1864; Vol. I., p. 273.

68

See above, Vol. I., p. 84.

69

'Old Deccan Days; or Hindu Fairy Legends, current in Southern India.' Collected from oral tradition by M. Frere. London, 1868; p. 25.

70

'Popular Tales from the Norse, translated by G. W. Dasent.' Edinburgh, 1859; p. 27.

71

'Sagen, Märchen und Lieder der Herzogthümer Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg,' von Karl Müllenhoff; Kiel, 1845; p. 336.

72

'Aberglaube und Sagen aus dem Herzogthum Oldenburg, herausgegeben von Strackerjan;' Oldenburg, 1867; Vol. I., p. 190.

73

'Aberglaube and Sagen aus dem Herzogthum Oldenburg, herausgegeben von Strackerjan;' Oldenburg, 1867; Vol. I., p. 375.

74

'Griechische und Albanische Märchen, gesammelt von J. G. v. Hahn;' Leipzig, 1864; Vol. I., p. 222, and Vol. II., p. 240.

75

'Wallachische Märchen, herausgegeben von A. Schott;' Stuttgart, 1845, p. 228.

76

Aix-la-Chapelle.

77

'Deutsche Märchen and Sagen, gesammelt von J. W. Wolf.' Leipzig, 1845; p. 472.

78

'Niederländische Sagen, herausgegeben von J. W. Wolf;' Leipzig, 1843; p. 466.

79

'Niederländische Sagen, herausgegeben von J. W. Wolf;' Leipzig, 1843; p. 648.

80

Taters is evidently synonymous with Tartars.

81

'Old Deccan Days; or Hindu Fairy Legends, current in Southern India.' Collected from oral tradition, by M. Frere. London, 1868; pp. 139, 273.

82

'Niederländische Sagen, herausgegeben von J. W. Wolf;' Leipzig, 1843. p. 230.

83

'Deutsche Volksfeste, von F. A. Reimann;' Weimar, 1839; p. 218.

84

'Popular Customs, etc., of the South of Italy,' by Charles Mac Farlane, London, 1846; p. 68.