полная версия

полная версияMusical Myths and Facts, Volume 2 (of 2)

The goblins in Sweden have their principal meetings at midnight before Christmas, and their amusements consist chiefly in music and dancing. They generally assemble in those isolated spots among the mountains where are found large stones resting on pillars, around which they delight to dance. It is considered decidedly dangerous to encounter them at their pastimes on Christmas Eve.

Many years ago, – some say it was so far back as in the year 1490, – a farmer's wife in Sweden, whose name was Cissela Ulftand, distinctly heard, on Christmas Eve, the wild music of the goblins who had assembled not far from her house. The farm in which the good woman lived is called Ljungby, and the group of curiously-placed stones around which the goblins had congregated is well known to many people; indeed, almost everyone in Sweden knows the Magle-Stone.

Well, when Mistress Ulftand heard the music, she spoke to one of her farm-servants, a strong and daring young fellow, and induced him to saddle a horse and to ride in the direction of the Magle-Stone, that he might learn something about the mysterious people, and tell her afterwards all he had seen. The lad rather liked the adventure; he lost no time in mounting his horse, and was soon galloping towards the scene of the music and rejoicing. In approaching the Magle-Stone, he somewhat slackened his speed; however, he drew quite near to the dancers.

After he had been gazing a little while at the strange party, a handsome damsel came up to him and handed him a drinking-horn and a pipe, with the request that he would first drink the health of the King and then blow the pipe. The lad accepted both, the drinking-horn and the pipe; but, as soon as he had them in his hands, he poured out the contents of the horn, and spurring his horse he gallopped off over hedges and ditches straight homewards. The whole company of goblins followed him in the wildest uproar, threatening and imploring him to restore to them their property; but the fellow proved too quick for them, and succeeded in safely reaching the farm, where he delivered up the trophies of his daring enterprise to his mistress. The goblins now promised all manner of good luck to the farmer's wife and her family, if she would return to them the two articles; but she kept them, and they are still preserved in Ljungby as a testimony to the truth of this wonderful narrative.

The drinking-horn is of a metallic composition, the nature of which has not been exactly ascertained; its ornaments are, however, of brass. The pipe is made of the bone of a horse. Moreover, the possession of these relics, we are told, has been the cause of a series of disasters to the owners of the farm. The lad who brought them to the house died three days after the daring enterprise, and the day following, the horse suddenly fell down and expired. The farm-house has twice burnt down, and the descendants of the farmer's wife have experienced all kinds of misfortunes, which to enumerate would be not less laborious than painful. It is only surprising that they should still keep the unlucky horn and pipe.

THE GOLDEN HARVEST

This is a genuine Dutch story. A long time may have elapsed since the hero of the event recorded was gathered to his fathers. Howbeit, his name lives, and his deeds will perhaps be longer retained by the people in pleasant remembrance than the deeds of some heroes who have made more noise in the world.

An old village crowder, whose name was Kartof, and who lived in Niederbrakel, happened once, late in the night, to traverse a little wood on his way home from Opbrakel, where he had been playing at a dance during the wake. He had his pockets full of coppers, and felt altogether mighty comfortable and jolly; for the young folks in Opbrakel had treated him well, and the liquor was genuine Old Hollands. But, there is nothing complete in this world, as the saying is, and as old Kartof was presently to experience to his dismay, when he put his hand into his pocket for his match-box. Had he not just filled his old clay pipe in the pleasant expectation, amounting to a certainty, that he should indulge in a comfortable smoke all the way home? And did he not feel, with a certain pride, that he deserved a good smoke after all his exertions with the fiddlestick? But what use was it to rummage his pockets for the match-box! It certainly was not there, and must have been lost or left behind somewhere.

"The deuce!" muttered old Kartof, "If I had only a bit of fire now to light my pipe, I should not care for anything else in the world, I am sure!"

Scarcely had he said these words, when he espied a light gleaming through the bushes. He went towards it, but it was much further off than it at first appeared to him; indeed, he had to go more than a hundred yards into the brush-wood before he came up to it. He now saw that it was a large fagot burning, around which a party of men and women, joined hand in hand, were dancing in a circle. "How odd!" thought old Kartof; but being a man accustomed to genteel society, he was at no loss how to address them politely; so, taking off his hat, he said: —

"Ladies and Gentlemen! Excuse me. I hope I am not intruding too much if I ask the favour of your permission to help myself to a little fire to light my pipe."

He had not even quite finished his speech, when several of the dancers stepped forward and handed him glowing embers in abundance. Now, when approaching him they perceived that he carried a violin under his arm, they importuned him to play for them to dance, intimating that he should be well rewarded for his services. "Why not?" said old Kartof: "It is only about midnight, and I can sleep to-morrow in the day-time; it will not be the first time that I have gone to bed in the morning."

While talking in this way, he tuned his instrument; and soon he struck up his best tunes, one after the other. But, though he played ever so much, he could never play enough, the dancers were so insatiable! Whenever his arm sank down from sheer fatigue, they threw a golden ducat into the sound-hole of his violin, which pleased him immensely, and always animated him to renew his exertions, especially also as they did not neglect to refresh him occasionally with a remarkably fine-flavoured Schiedam, from a bottle so oddly-shaped that he had never seen anything like it, so funny it was. He could not help smiling whenever he looked at the bottle.

Gradually his violin became heavier – of course, that was from the golden ducats which the dancers continually threw into it. But also his arm became heavier, and at last old Kartof felt altogether too heavy, sank softly down, and fell asleep.

How long he lay in this state no one knows, nor is ever likely to know. But, thus much is certain, when old Kartof awoke the day was already far advanced, and the sun shone brightly upon his face. He rubbed his eyes and looked about, doubtful whether he was a man of property or whether he had only dreamt of golden ducats. There was the violin lying in the grass near his feet. He hastily took it up; – it felt as light as usual. He shook it; – no rattling of ducats. He held it before his face and peeped into the sound holes; – to be sure, there was something in it, yellow and glittering like gold. He shook it out on the grass; – what should it be? – a score or two of decayed yellow birch-leaves.

Disappointed, old Kartof rose to his feet to look around whether he could not find the place where the fire had been.

Yes, there it was! Some embers were still glimmering in the ashes. This appeared to him more odd than anything else he had experienced. But old Kartof, after all, took the matter quietly enough. He lighted his pipe, and taking up his violin set out on his way home, resolving as he went never to go to that confounded place again after twelve o'clock at midnight.78

GIPSIES

There prevails in popular traditions much mystery respecting gipsies. No wonder that this should be the case, since these strange vagabonds are in most countries so very different from the inhabitants in their appearance and habits; and their occupations are often so well calculated to appeal to the imagination of superstitious people, that a gipsy is regarded by them almost as a sorcerer. His better-half not unfrequently pretends to be a soothsayer, and he is often a musician. However different the gipsy hordes which rove about in European countries may be from each other in some respects, they are all fond of music, magic, and mysterious pursuits. Among the gipsy bands in Hungary and Transylvania talented instrumental performers are by no means rare; and in Russia, the gipsy singers of Moscow enjoy a wide reputation for their musical accomplishments. It is told, – not as a myth but as a fact, – that when the celebrated Italian singer Signora Catalani heard in Moscow the most accomplished of the gipsy singing-girls of that town, she was so highly delighted with the performance that she took from her shoulders a splendid Cashmere shawl which the Pope had presented to her in admiration of her own talent, and embracing the dear gipsy girl, she insisted on her accepting the shawl, saying that it was intended for the matchless cantatrice which she now found she could not longer regard herself.

There is a wildness in the gipsy musical performances, which admirably expresses the characteristic features of these vagrants. Indeed theirs is just the sort of music which people ought to make who encamp in the open air, feed upon hedgehogs and whatever they can lay hand on, and profess to be adepts in sorcery and prophecy.

The following event is told by the peasants in the Netherlands as having occurred in Herzeele. A troop of gipsies had arrived in a valley near that place. They stretched a tight rope, on which they danced, springing sometimes into the air so high that all who saw it were greatly astonished. A little boy among the spectators cried: "Oh, if I could but do that!" —

"Nothing is easier," said an old gipsy who stood near him: "Here is a powder; when you have swallowed it, you will be able to dance as well as any of us."

The boy took the powder and swallowed it. In a moment his feet became so light that he found it impossible to keep them on the ground. The slightest movement which he made raised him into the air. He danced upon the ears of the growing corn, on the tops of the trees, – yea, even on the weather-cock of the church-tower. The people of the village thought this suspicious, and shook their heads, especially when they furthermore observed a disinclination in the boy to attend church. They, therefore, consulted with the parson about the boy. The parson sent for him, and got him all right on his legs again by means of exorcism; but it was a hard struggle to banish the potent effects of the gipsy's powder.79

The gipsies were formerly supposed to be descendants of the ancient Egyptians. The German peasants call them Taters,80 a name indicating an Asiatic origin; and it has been ascertained that they migrated from Western India. The roving Nautch-people in Hindustan are similarly musical and mysterious.

THE NAUTCH-PEOPLE

The Nautch-people in Hindustan are not only singers and dancers who exhibit their skill before those who care to admire and to reward them; but they possess also dangerous charms.

In a popular story of the Hindus, called 'Chandra's Vengeance' we are told of a youth who, on hearing the music of the Nautch-people at a great distance, is irresistibly compelled to traverse the jungle in search of them. When, after twelve days' anxious endeavour to reach them, he discovers their encampment, Moulee, the daughter of the chief Nautch-woman, approaches him singing and dancing, and throws to him the garland of flowers which she wears on her head. He feels spell-bound, and the Nautch-people offer him a drink which, as soon as he has tasted it, makes him totally forget his family and his dear home. So he remains with the Nautch-people, and wanders with them about the country as one of the company.

Again, in a Hindu story called 'Panch-Phul Ranee,' a Rajah, or King, is enchanted by the Nautch-people, so that he finds his happiness in roving with them from place to place, and in beating the drum for the dancers. His enchantment is accomplished in this way: He had set out on a journey, leaving his wife and infant son behind. One day he happened to fall in with a gang of Nautch-people, singing and dancing. He was a remarkably handsome man, and the Nautch-people, on seeing him approach, said to each other "How well he would look beating the drum for the dancers!" The Rajah was hungry and told them that he required some food; whereupon one of the women offered him a little rice, upon which her companions threw a certain powder. He ate it, and the effect was that it made him forget his wife, child, rank, journey, and whatever had happened to him in all his life. He willingly remained with the Nautch-people, and wandered about with them, beating the drum at their performances, full eighteen years. His son, the prince, being now grown up, could no longer be detained from setting out in the world in search of his beloved father. After many fruitless attempts the prince discovered his father among the Nautch people, – a wild, ragged-looking man whose business it was to beat the drum. The joyful prince summoned the wisest doctors in the kingdom to restore the Rajah to his former consciousness; but their exertions did not at first prove at all successful. In vain did they assure the old drummer that he was a Rajah, and that he ought to remember his former greatness and splendour. The old man always answered that he remembered nothing but how to beat the drum; and, to prove his assertion, he treated them on the spot with a tap and roll on his tom-tom. He really believed that he had beaten it all his life.

However, through the unabated exertions of the doctors, a slight remembrance came gradually over him; and by-and-by his former mental power returned. He now recollected that he had a wife and a son. He also recognized his old friends and servants. Having reseated himself on the throne, he governed as if nothing had ever occurred to interrupt his reign.81

THE MONK OF AFFLIGHEM

The aim of the present series of popular stories demands that some notice should now be taken of such musical legends as breathe a thorough Christian spirit. Several of these are, as might be expected, very beautiful; but they are familiar to most readers. One or two which are less well known may, however, find a place here.

The legend of the Monk of Afflighem bears some resemblance to the beautiful tradition of the Seven Sleepers. If it fails to interest the reader, the cause must be assigned to the simple manner in which it is told rather than to the subject itself.

Towards the end of the eleventh century occurred in the Abbey of Afflighem, in Dendermonde, East Flanders, a most wonderful event, the pious Fulgentius being at that time the Abbot of the monastery.

One day, a monk of very venerable appearance, whom no one remembered to have seen before, knocked at the door of the monastery, announcing himself as one of the brotherhood. The pious Abbot Fulgentius asked him his name, and from what country he had come. Whereupon the monk looked at the Abbot with surprise, and said that he belonged to the house. Being further questioned, he replied that he had only been away for a few hours. He had been singing the Matins, he said, in the morning of the same day in the choir with the other brothers. When, in chanting, they came to the verse of the ninetieth psalm, which says: "For, a thousand years in thy sight are but as yesterday!" he pondered upon it so deeply that he did not perceive when the singers left the choir, and he remained sitting alone, absorbed by the words. After he had been a while in this state of reflection, he heard heavenly strains of music, and on looking up he saw a little bird which sang with a voice so enchantingly melodious that he arose in ecstasy. The little bird flew to the neighbouring wood, whither he followed it. He had been only a little while in the wood listening to the heavenly song of the bird; and now, in coming back he felt bewildered, – the appearance of the neighbourhood was so changed he scarcely knew it again.

When the pious Abbot Fulgentius heard the monk speak thus, he asked of him the name of the Abbot, and also the name of the King who governed the country. And after the monk had answered him and mentioned the names, it was found to the astonishment of all that these were the names of the Abbot and the King who had lived three hundred years ago. The monk startled, lifted up his eyes, and said: "Now indeed I see that a thousand years are but as one day before the Lord." Whereupon he asked the pious Abbot Fulgentius to administer to him the Holy Sacraments; and having devoutly received them, he expired.82

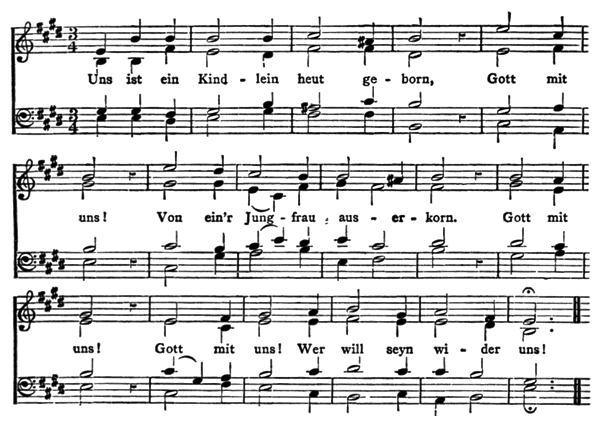

THE PLAGUE IN GOLDBERG

The inhabitants of Goldberg, a town in Germany, observe an old custom of inaugurating Christmas, which is peculiar to themselves. Having attended divine service, which commences at midnight on Christmas Eve, they assemble at two o'clock to form a procession to the Niederring, a hill situated close to the town. When the procession has arrived at the top of the Niederring, old and young unite in singing the Chorale Uns ist ein Kindlein heut geboren ("For us this day a child is born"). As soon as this impressive act of devotion is concluded, the town band stationed in the tower of the old parish church performs on brass instruments the noble Chorale Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr ("All glory be to God on High"), which in the stillness of the night is heard over the whole town, and even in the neighbouring villages.

The origin of this annual observance dates from the time when the town of Goldberg was visited by a deadly plague called Der schwarze Tod ("The black Death"). According to some accounts the awful visitation occurred in the year 1553; at all events this date appears to have been assigned to it on an old slab embedded in the wall of the parish church of Goldberg; but the inscription has become so much obliterated in the course of time, that no one can make out the year with certainty. Thus much, however, is declared by all to be authentic: The plague spread throughout the town with frightful rapidity. The people died in their houses, in the streets, everywhere, at night, and in the day-time. Some, while at their work, suddenly were stricken and fell down dead. Some died while at their meals; others while at prayers; others in their endeavours to escape the scourge by hastening away from the doomed town. Indeed, it was as if the Angel of Death had stretched out his hand over the place, saying "Ye are all given up to me!"

The plague raged for some weeks, and then quietness reigned in Goldberg. The few survivors had shut themselves up solitarily in their houses, not knowing of each other; for, no one now ventured into the street; neither did anyone open a window, fearing the poisonous air; for the corpses were lying about, and there remained none living to bury the dead.

Such was the condition of Goldberg in the month of December, just before Christmas. On Christmas Eve one of the solitary survivors, deeply impressed with the import of the holy festival, attained the blessing of a firm trust in the wisdom of the inscrutable decrees of Providence. He thought of the happy time of his childhood when his parents lighted up for him the glorious Christmas tree; and this recalled to his mind the simple and impressive Christmas hymn which his mother had taught him to recite on the occasion. Strengthened by devout contemplation, he ventured to open the window. The night was beautiful, and the air wafted to him so pure and delicious that he resolved to leave his prison. At the second hour after midnight he went out of the house, and bent his steps through the desolated streets towards the Niederring. Arrived at the top of the hill he knelt down and sang from the depth of his heart the Christmas hymn.

His voice was heard by another solitary survivor, who perceiving that he was not, as he had supposed, the only person still living in Goldberg, gained courage and likewise from his hiding place repaired to the Niederring, and kneeling down joined the singer with sincere devotion. Soon a third person made his appearance, slowly drawing near like one risen from the grave. Then a fourth, a fifth, until the number of them amounted to twenty-five; and these were all the inhabitants of Goldberg who had escaped the ravages of the Black Death.

The Christmas Chorale sung in the refreshing mountain air wonderfully invigorated their desponding spirits. They arose and solemnly vowed henceforth to unite in Christian fellowship, with reliance upon the wisdom of the divine ordinances. The next day they buried their dead; and when their vow became known in the neighbourhood, many good people were drawn to Goldberg. The town soon revived, and prospered more than ever.

The inhabitants have not forgotten the visitation which befel their forefathers, but remember it in humiliation; and this is a lasting blessing.83

FICTIONS AND FACTS

Knowledge is, of course, to superstition as light is to darkness; still, some nations endowed with a lively imagination, although they are much advanced in mental development, cling to the superstitions of their forefathers, since the superstitions accord with their poetical conceptions, or are endeared to them by associations which pleasantly engage the imaginative faculties.

Besides, in countries where the inhabitants frequently witness grand and awful natural phenomena, their poetical conceptions are likely to be more or less nourished by these impressive occurrences, however well acquainted they may be with their natural causes.

It is therefore not surprising that many superstitious notions, such as have been recorded in the preceding stories, should be found in civilized nations.

Moreover, in some countries, a more careful research into the old traditions harbouring among the uneducated classes of the people has been made, than in other countries. It would, therefore, be hasty, from the sources at present accessible, to judge of the degree of mental development attained by individual nations. The Germans are not less rational than the English; nevertheless, a far greater number of Fairy Tales have been collected in Germany than in England.

An enquiry into the musical traditions of the different European races is likely to increase in interest the more we turn to the mythological conceptions originally derived from Central Asia, and dispersed throughout Europe at a period on which history is silent, but upon which some light has been thrown by recent philological and ethnological researches.

A word remains to be said on the musical myths of modern date. We read in the biographies of our celebrated musicians facts which would almost certainly be regarded as fictions, were they not well authenticated. On the other hand, it would not be difficult to point out modern myths referring to the art of music. Tempting as it might be to cite the most remarkable examples of this kind, and anecdotes relating to musicians in which fiction is strangely mingled with fact, it is unnecessary to notice them here; for, are they not written in our works on the history of the art and science of music?

DRAMATIC MUSIC OF UNCIVILIZED RACES

The first music of a dramatic kind originated probably in the passion of love. Savages, unacquainted with any other dramatic performances, not unfrequently have dances representing courtship, and songs to which these dances are executed. However rude the exhibitions may be, and however inartistic the songs may appear, – which, in fact, generally consist merely of short phrases constantly repeated, and perhaps interspersed with some brutish utterances, – they may nevertheless be regarded as representing the germ from which the opera has gradually been developed. Dancing is not necessarily associated with dramatic music; the dances of nations in a low degree of civilization are, however, often representations of desires or events rather than unmeaning jumps and evolutions.