Полная версия

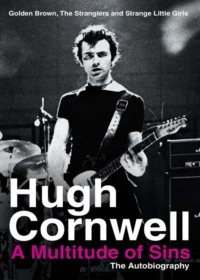

A Multitude of Sins: Golden Brown, The Stranglers and Strange Little Girls

Hugh Cornwell

A Multitude of Sins

The Autobiography

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Foreword

Prelude

1 Leave Me Alone

2 Rock ‘n’ Roll Part 1

3 Let me tell you about Sweden

4 Rock ‘n’ Roll Part 2

5 Sex

6 Drugs

7 Inside information

8 Making It

9 USA

10 Celebrity

11 Rest of the World

12 Heroes

13 The Other Three

14 Standing Room Only

15 Creativity, Cricket & Cadiz

Hugh Cornwell career flow sheet

Discography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

PICTURE CREDITS

Copyright

About the Publisher

Foreword

by Martin Roach

‘Have you tried goat’s milk?’

Hugh Cornwell, it seemed, had tried everything. I’d heard all about him, of course. About The Stranglers, about the drugs, the women, the violence, the songs, the drugs, the prisons, the controversy, the drugs …

And here he was, sitting in my front room, listening to me bleat on about the on-going health problems I suffer following a fabulous but ill-fated canoe trip down the Amazon years ago.

I hadn’t tried goat’s milk, no. Hugh said it was healthy and easy to digest, adding – in between sips from a cup of herbal tea – that it might just be worth a try.

This was just one of many incidents that bemused and yet delighted me while working with Hugh. I’d been asked to edit his life story and must admit to having felt some trepidation when his literary agent first called with the proposal. What? Work with a man who’d served time, taken more drugs than even rock ‘n’ roll’s licentious past would expect and caused more trouble than a smouldering cigarette in a firework factory? Possibly more worrying was the fact that Hugh was going to write the entire opus himself. So, yes, I have to admit to wondering whether Hugh would be up to the challenge.

I knew he would be after reading the very first sentence he e-mailed me … I should have known. After all, his musical quill has inked many songs that are rooted deep into the nation’s psyche. The jump from writing a classic song to an autobiographical book is a strange leap, but it’s one he has managed with finesse. When I did come across areas where I wanted to know more, I asked Hugh some very awkward questions. First, he would ask me why I wanted to know and then he would go away and, without a shred of resentment and always within a few hours, fill my Inbox once again. So, in many ways, Hugh has been the easiest person I’ve ever had to work with.

At the same time, we’ve argued – always with good humour – long into the night over a single word, a twist of grammar or a disputed turn of phrase. On a few occasions, he would not back down. And, on many occasions, he was right.

Some people might wonder if it is really necessary to go into such minute detail. However, I realized very early on in the process that to Hugh every word did matter, because every word represented an experience that counted, every sentence recalled a period in his life that was vital and every single syllable was there for a reason.

Of course, the text he religiously and diligently sent me had every Bacchanalian excess that I’d expected … and then some. However, more surprisingly, the words screaming down the fibre optics from the West Country to Essex were also rich in thought, musings, theories, opinions and ideas. On his countless treks around the world – while we were working together he was often away, but always available – he seemed to be an itinerant life magnet, scouring the globe for new encounters before returning back laden down with more souvenirs for his soul. If your experiences could literally be crammed into a suitcase at the end of each trip, then Hugh Cornwell would have the biggest excess baggage bill in aviation history.

Never having claimed to match rock ‘n’ roll’s finest for debauchery, I have always had to rely on a vicarious duality, experiencing lives that I could never, or would never, see myself. In living Hugh’s life these past months, I’ve had one hell of a ride.

On one occasion, I asked Hugh what on God’s green earth had gone through his mind when, faced with a knife caked in amphetamine held under his nose by a Hell’s Angel, he chose to snort the lot. ‘It just seemed polite,’ he said, raising his eyebrows.

When we finished the final draft of the manuscript, I dragged a cork out of a bottle of red wine and collapsed in front of the television for some mental respite. Channel-hopping through the usual banal Saturday night schedules, I flicked on to BBC 2 and a programme called The Rise of the Celebrity. After about thirty seconds, Hugh’s face loomed large on my old Toshiba, singing ‘No More Heroes’ on Top of the Pops. The archive footage was interspersed with a 2004 interview featuring that angry punk’s latter-day alter ego, the Hugh Cornwell I have come to know. And suddenly, everything made perfect sense.

Martin Roach, Editor, June 2004

PS. The goat’s milk worked.

Prelude

It occurred to me that it might be an idea to welcome you to this book. Although it’s an autobiography, I’ve tried to avoid a strict chronological order, basically to introduce some elements of surprise. I’ve also tried to keep it pretty much as a stream of consciousness, as that’s the way we think when we’re going about our lives. Events have popped up in my memory in a completely haphazard way, and I’ve tried to convey that while I’ve been writing. I started to write the book in my head, but I first put pen to paper in southern Spain a couple of years ago, when I wrote the opening chapter just to see how it would turn out.

Any Stranglers fan will probably want to cut to the quick, thinking that there can’t be anything worth reading that can remotely compare to that period of my life. However, there was a ‘Before’ and there most definitely is an ‘After’. But if you want to find out about the formation of the band, then the chapter ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Part 2’ is probably what you’re looking for. Chapter 1, ‘Leave me alone’, deals with my leaving the band. ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Part 1’ deals with school, university and my first trip to Sweden. If you want the riots, then go to ‘Rest Of The World’. If you want to hear about how I lost my virginity then go to ‘Sex’. If you want to find out about my band Johnny Sox and bank robberies in Sweden then go to ‘Let me tell you about Sweden’. ‘Drugs’ will tell you how I happened to end up in Pentonville for five weeks. ‘Standing Room Only’ tells you what I’ve been up to recently amongst other things. The other chapter titles speak for themselves.

I’d like to say something about the nature of memory while we’re not on the subject. One of my favourite books is called My Last Breath by the Spanish film-maker Luis Buñuel, which is his attempt at an autobiography. At the beginning, he tells a little story about how his memory plays tricks on him. He recalls finding a photograph from a friend’s wedding in the Twenties, and is surprised to see someone in the picture whom he didn’t expect to have attended the event. He telephones the bridegroom to ask about the presence of the guest, to be told that he himself was the one who didn’t attend the wedding. This amazes him, as he can remember a lot of things about it even though it transpired he wasn’t actually there. He must have heard so many stories from his friends who were there that his mind had appropriated the experience. I looked up the story to refresh my memory of it, only to find it completely different from what I had remembered. I rest my case.

So you may wonder how much of this is true. Well, as far as my memory serves me, it all is. Looking at it, I realize I couldn’t have made up better fiction if I’d tried. It’s precisely because it’s true that it has been so easy to write, as I haven’t had to scratch my head looking for any plot and character development. But it has been very different from the writing of songs that I’ve been involved in for the last thirty years, and harder too, because when you write a song, you’ve got the music to guide you. But I’ve really enjoyed the experience, even though my brain is now feeling a bit frazzled. I’m sure there’s a lot of things I haven’t been able to remember, but all the meat is here. One thing to bear in mind is that the truth depends upon where you’re standing at the time, and I totally understand it if another person disagrees with anything I’ve written.

One thing that may come as a surprise is the fact that I’ve been allowed to write this myself, without a ghost writer. Obviously HarperCollins wanted to live dangerously, and I’m very glad they did. Martin Roach has been a fantastic help as an editor, being such a seasoned writer himself. He has guided me through a lot of structural and grammatical errors, and has always been there with enthusiasm and encouragement whenever I’ve needed it. So without his input this book would definitely not have existed. I have to add that David Buckley’s biography of The Stranglers, No Mercy, has been very useful to refer to, as his chronicling is superb, even though my input to that book was very small. I’ve explained how a few key Stranglers’ songs came into existence and what they’re about, but for the full story about every song then I can recommend my previous book, The Stranglers: Song By Song which I put together with my friend Jim Drury.

I would also like to take this opportunity to express my gratitude to Hans Wärmling, the fifth Strangler. It was he who acted as my mentor when I was in Sweden the second time, and encouraged me to play electric guitar, to sing, and to write songs. I am sure things wouldn’t have turned out quite the same way if I’d never met him. He was a very nice man, and acted as a fine example of hard work and dedication for me in those early days when I wasn’t sure where my destiny lay.

Hugh Cornwell

Cádiz, Spain, June 2004.

CHAPTER ONE Leave me alone

You can probably guess what questions I get asked most.

‘WHY DID YOU LEAVE THE STRANGLERS?’ and:

‘WHEN ARE YOU GOING TO GET BACK WITH THE GROUP?’

And whatever answer I give, however lucid it might be, the questioner always looks at me with that ‘there-must-be-more-to-it-than-that’ look. So, I thought it would be a perfect way to start this book by answering these two questions finally, definitively … forever.

ROOM INTERIOR. SWISS COTTAGE HOLIDAY INN. 11 AUGUST, 1990. 5P.M.

The Stranglers are headlining a sold-out show at Alexandra Palace in north London, sponsored by Capital Radio. The gig is going to be filmed and we’ve done a lengthy sound-check earlier in the afternoon. I’m watching England bat against India in the second Test Match at Old Trafford on TV. The ninth wicket has gone down and Devon Malcolm, England’s number eleven, strolls out to the wicket. My interest perks up as Malcolm is always good for a laugh to watch, being such a terrible batsman. He takes guard and after a couple of almighty swings, he manages to connect with the ball, which goes sailing out into one of the stands for a six. Malcolm is all smiles and the crowd has woken up to cheer him on. Unexpectedly, I suddenly identify with this character and recognize that the effort being made to fight his way out of the straitjacket situation in which the Indian bowlers have placed him, perfectly mirrors my own current, repressed state within the group. As I watch the ball soar high over the turf, it comes to me in a flash that I should leave The Stranglers, tonight, after the gig.

Thinking for a while, I realize that the momentous decision I have just made has been staring me in the face for a long time, but I could not accept it any earlier as being the solution. The more I think about it, the more obvious it becomes. I cannot believe how I have managed to avoid considering leaving for so long, and the word

DENIAL

pops into my brain. When a moment like this occurs, it feels like the top of your head is going to explode, rather like having a hit of freebase cocaine. I want to share this moment with someone and celebrate the end of an era of uncertainty, but understand there’s no way I can say a word to anyone, just in case I change my mind in a few hours’ time.

Inevitably, Devon Malcolm gets himself out and his moment passes, but mine continues. The teams traipse off the field for a break between the innings and I’m left to weigh up the consequences of my decision. I feel terribly guilty and start to think I should have seen it all earlier. Therefore I have been deceiving everyone, including myself. But that’s a ridiculous conclusion to come to. I acknowledge this and stop feeling like crap. I remember the last time I felt like this, living in Sweden in 1974, when I handed in my notice to my professor at Lund University and stopped my PhD. That night I went to sleep thinking that I wasn’t going to wake up the next day, or that someone was going to switch off my daylight (see lyrics to ‘Always The Sun’). But the next day did come and to my surprise it was brilliantly sunny. The only difference was I didn’t have to go into the laboratory. That’s the trouble with commitment and loyalty, it brings with it a sense of obligation, accompanied by insecurity and a fear of the unknown, which creeps into the void created when you leave a situation.

BACK TO THE HOTEL ROOM

It’s getting to the time to prepare for the gig and I’m not feeling any different. I am convinced that I’ve finally seen the light at the end of the tunnel and I just want to get on with it. I go through all the little rituals I do to prepare for a gig: I have a cat nap for about ten minutes, I have a shit and a shave, I check that my shoelaces are tight but not too tight, and I wait for the call down to the hotel lobby.

As usual, no one says much during the ride to the venue. John Ellis, ex-Vibrators, is with us on this tour as a second guitarist and he is the most talkative. I promise myself that I will put everything into this concert as it’s going to be my last one as a Strangler. Normally a live set goes quicker than you would expect, but this one just races by. Before I know it, we are on stage doing an encore or two and then it’s all over and we are backstage in a caravan winding down. Someone asks me something about next week and I mutter an incoherent answer over my shoulder as I change my clothes. It’s been a good performance and the last thing I want to do is bring everyone down by announcing my news to the rest of the group. I make some excuses and manage to get away as soon as I can. I pass John Ellis on the way out the door, and I say, ‘Have a nice life’ to him, probably because he’s an outsider and has nothing to do with my decision. I grab one of the courtesy cars at our disposal and get a ride into Soho, where I get paralytically drunk with some unsuspecting friends …

Anyone who has been in a professional band for any length of time can tell you that it resembles being in a marriage without the sex. Long periods of time are spent in one another’s company; there are many shared experiences, in sickness and in health, for richer for poorer, etc, etc. It does help if you share a similar sense of humour or have similar tastes, but most of all, you have to enjoy each other’s company. Apparently, Sam & Dave, the immortal soul singers, only meet when they take to the stage together, and when the show is over they exit from different sides of the theatre.

Maybe I wouldn’t have left the group if I’d been having sex with one of them. To be really safe, maybe I should have been shagging them all. The only trouble is, gee whiz, I’m not that way inclined. As Sam Kinnison, the American stand-up comedian used to say, ‘I can’t stand the hairy backs.’

So I guess you can reach the conclusion that I wasn’t enjoying the company of Messrs Black, Burnel and Greenfield any more. When we first got together, we were finding out so much about each other. There was always something to ponder over and be curious about. I suppose we had got to know each other so well by 1990 that there was nothing left to find out, or nothing left that I was interested in. To spend sixteen years with one person is quite an achievement. I’d spent it with all three of them.

We had been working continuously together for all those years by the time I left and I remember one moment when the passage of time became a realization. We had returned to The 100 Club in Oxford Street, London, to play a secret gig prior to a tour, having last played there some seven or eight years previously. I found myself there in the afternoon while Jet was setting his drums up. I heard him laughing to himself. He was sitting on his drum stool and had recalled the last gig we’d played there all those years before. He’d remembered taking his watch off and finding a space in a brick wall beside him in which to put it. He had then forgotten about it until that moment and had checked the spot. Not only was the watch still there, but it was still keeping time. Passage of time is barely perceptible unless you can see that something has changed. The trouble is that The 100 Club still looks more or less the same as it did in the Sixties.

By contrast, I was a regular at another Soho club just round the corner, The Marquee, which no longer exists. It was there that I saw The Who, The Yardbirds (with Beck, Page and Clapton all playing together in the same line-up on one occasion), The Spencer Davis Group, and my favourites, The Graham Bond Organisation, with Graham Bond on organ, mellotron and soprano sax, Dick Heckstall-Smith on sax, Jack Bruce on bass and Ginger Baker on drums (they had tried out John McGoughlin on guitar but had sacked him). Then there was The Mark Leeman Five and The Action.

I was still at school and I’d go there by myself maybe twice a week. After the gig I’d get the Tube home and be back before midnight. One night a dodgy man in a raincoat offered me some purple hearts as I walked back to the Tube station. The Marquee was a very, very cool place, and hardly anyone spoke to one another, or barely moved. They just stood still and listened to the bands. It was perfectly portrayed by Michelangelo Antonioni in his film, Blow Up, in which The Yardbirds are playing and Jeff Beck destroys his guitar and throws it into the crowd as an offering. Going back there with The Stranglers it seemed a lot smaller, but it was a thrill for me. We played there once in the early days for a fiver supporting Ducks Deluxe, who shared the same management as us. After the gig we packed our equipment back into the ice-cream van and I went to collect the fiver from Sean Tyla of Ducks Deluxe, as instructed by Dai Davies, one of the managers. Sean fobbed me off a couple of times, saying he hadn’t been paid yet and I’d have to wait. I finally got it out of him about two hours later, and had great pleasure seeing him six months later when his new band The Tyla Gang were supporting us at Oxford Polytechnic.

But to get back to the point, it just wasn’t happening for me in The Stranglers anymore. The last thing I wanted to do was to go through the motions and become an anachronism. The whole band had grown apart. When, we started out, we were each other’s family. One by one, the band members started their own families and we stopped relaxing together. We’d meet up, rehearse, disperse, reconvene at a studio, record, disperse again, and the same thing would happen when a tour was scheduled. I had no idea what any of the other three were up to outside of when we worked together. It really had become a day job and you know what they say about that. But I did give it up and I feel much better for it. I just couldn’t see myself being in a group at the age of fifty, but I could see a future making music.

I was also getting tired of compromising. In a group, there is a certain amount of democracy or it won’t function. A group’s collective psyche or image is a mixture of all the things that everyone brings in, and the less you bring in, the less of you is found in the collective psyche. The Stranglers’ coat didn’t fit me anymore. I didn’t feel like one any longer and the more I thought about it, the less comfortable I felt, and the less satisfied I became. I was writing more and more by myself, creating even more of a distance from the others. While we were working on the last studio album I was on, called 10, I was accused of trying to turn it into a solo album, because I was layering harmonies on top of my own voice on a song I’d written, which the others had approved for the album.

A big paradox of the punk movement occurred to me recently. Most of all the significant bands of that period are alive and well and still performing more or less the way they were back then. This seems funny, considering it was a nihilistic movement and yet there was only one star casualty, namely Sid Vicious. But the reason is simple enough. The bands are still there because it pays the rent. There’s nothing wrong with that, it’s the ethic behind why most people all over the world do their jobs every day. But I did take a huge financial risk when I left The Stranglers. We were due to sign a new publishing deal soon afterwards that would have brought in a fat cheque for us to share, but I knew to stick around just for that didn’t make any sense. Any decent lawyer would have smelt a rat if I’d left after signing, and we’d have been sued. The funny thing is, we’d very nearly split up years before when Dai Davies and Derek Savage, our first managers, suggested we should call it a day after the first three albums, which we’d released in the unbelievably short period of just fourteen months.

After I left, our accountants clarified that our greatest money-making period had been in those first frenetic years. Our first three albums had cost very little to make, and our tastes were sufficiently crude then that we didn’t expect the luxuries one can get accustomed to. We were so delighted to be successful that we failed to realize we weren’t actually taking home much money. Our managers knew that as long as we had everything we needed, we would be content enough to carry on regardless. On several occasions, a planned tour of Europe would come in costing more than it generated in concert fees, so our managers would go to the record company asking them to pay the difference. This they would do, but charge it against our royalties. The managers would leave with the cheque for the shortfall, and then promptly take their commission off, leaving the tour still in the red, and them in the black. We would go and do the tour, staying in five-star hotels, not realizing that we were paying all the costs. This all helps to paint the picture of a golden goose laying eggs which everybody gets a nice piece of … except the goose. I think it’s pretty accurate. I somehow feel that this part of my story is probably the same as that of a lot of musicians, but I’m not complaining. After all, I got to perform on stage, I got to shag the birds, and I got to take the drugs and drink the booze. And I got my picture in the paper!

The unsung heroine of the punk era is Shirley Bassey. If she hadn’t been selling truckloads of records in the mid-Seventies, United Artists Records wouldn’t have been able to sign The Stranglers, Buzzcocks, Dr Feelgood, 999, Wire and many others. She was the ‘cash cow’ of punk and has never realized it. She also provided us with our first record producer, Martin Rushent, who was the straightest person any of us knew apart from our parents. He’d been producing Shirl’s records for a while and was assigned by the record label essentially to record what we did in live performance. Originally it was thought that we’d release a live album, but as soon as we got into TW Studios in Fulham, with Martin and Alan Winstanley (the house engineer), we were able to improve on our live performance. We’d already recorded demos at TW Studios before being signed to the label, so we had suggested to United Artists that we go there again.