полная версия

полная версияThe Country of the Dwarfs

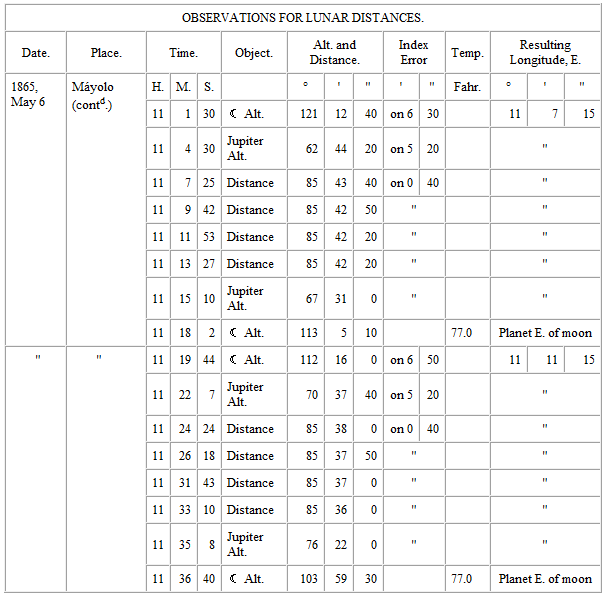

The following example will show you how a lunar distance is taken with a sextant:

Take as many lunar observations as you can east and west of the moon – the more the better – and you will be able to know your exact longitude with more certainty. It would be here too complicated to tell you how to make the calculations, but I am sure that after a while many of you would be able to make them.

By lunar observations, if sickness or some other cause has made you forget the day of the month, or even the year, you can find it again. Several times I lost my days while traveling.

The heat was intense at Mayolo. The rays of the sun were very powerful, and raised the mercury nearly to 150°. Just think of it! In order to know the heat of the sun, the thermometer was only a glass tube supported by two little sticks. I had to take care that the rays of the sun fell always perpendicularly on the mercury.

CHAPTER XVIII

SAYING GOOD-BY. – A PANIC-STRICKEN VILLAGE. – PACIFYING THE PEOPLE'S FEARS. – A TIPSY SCENE. – MAJESTY ON A SPREE. – LUNCH BY A RIVER SIDEOn the 30th of May, early in the morning, there was great excitement in Mayolo's village. That morning we were to leave for the Apono country. Mayolo himself was to take me there, and we were all getting ready, the men carefully arranging their otaitais. The horns were blown as the signal for our departure, and we took the path in single file, Igala leading, and Mayolo and I bringing up the rear.

"Good-by, Oguizi!" shouted the people. "Don't forget us, Oguizi! Come back, Oguizi!"

Following a path in the prairie, we traveled directly east. Our road lay among the ant-hills, which could be counted by tens of thousands, of which I gave you a description in my "Apingi Kingdom." After a march of seven miles we came to Mount Nomba-Obana. Mayolo once lived on the top of this mountain, but moved his village to its base, and afterward went to the place where I found him. At the foot of Nomba-Obana, on the somewhat precipitous side, were great quantities of blocks of red sandstone, and in this neighborhood we saw the ruins of Mayolo's former village. Mayolo is always changing his home, for he fancies that the places he occupies are bewitched.

At a distance of about three miles from Nomba-Obana we came to a stream called Ndooya, which we forded, but in the rainy season it must be a considerable body of water. We were approaching the Apono villages, and I felt somewhat anxious, for I did not know what kind of reception the people would give me. Groves of palm-trees were very abundant, and I could see numerous calabashes hanging at the tree-tops, ready to receive the sap, which is called palm wine.

At last we came in sight of the village of Mouendi, where we intended to stay. The chief was a great friend of Mayolo. As soon as the inhabitants saw me a shout rent the air. All the people fled, the women carrying their children, and weeping. The cry was, "Here is the Oguizi! Oguizi! Now that we have seen him, we are going to die." I saw and heard all this with dismay.

We entered the village. Not a soul was left in it; it was as still as death. I could see the traces of hurried preparations for flight as we continued our march through the street of this silent village till we came near the ouandja. There I saw Nchiengain, the chief, and two other men, who had not deserted him. These were the only inhabitants we could see. The body of the chief was marked, striped, and painted with the chalk of the alumbi. He seemed filled with fear; but the sight of Mayolo, his nkaga, "born the same day," seemed somewhat to reassure him.

Mayolo said, "Nchiengain, do not be afraid; come nearer. Do not be afraid. Come!" Then we went under the ouandja, and seated ourselves. In the mean time, I had taken a look at Nchiengain. He was a tall, slender old negro, with a mild and almost timid expression of countenance.

Then Mayolo said, "I told you, Nchiengain, that I was coming with the Oguizi. Here we are. The Spirit has come here to do you good – to give you beads, and many nice things. Then he will leave you after a while, and go still farther on."

Then I spoke to Nchiengain in his own language, for the Aponos speak the same language as the Ashira and Otando people. I said, "Nchiengain, do not be afraid of me. I come to be a friend; I come to do you good. I come to see you, and then will pass on, leaving beads and fine things for your women and yourselves. Look here" – pointing to all the loads which my Otando porters had laid on the ground – "part of these things will be for your people," and immediately I put around his neck a necklace of very large beads, and placed a red cap on his head. I then gave necklaces of smaller beads to the two other men, and said, "Nchiengain, you will have more things, but your people must come back; I do not like to live in a village from which all the people have run away. Mayolo's people did not run away, and you do not know what great friends we are. Call your people back."

I then went around the village, and hung a few strings of beads to the trees, and Nchiengain shouted, "Come back, Aponos; come back! Do not be afraid of the Spirit. As you come back, look at the trees, and you will see the beads the Spirit has brought for us, and which he will give to us." The two men then went out upon the prairie and into the woods, and before sunset a few men and women, braver than the rest, returned to the village, taking with them the beads which they had seen hanging from the branches of the trees.

In the evening the bright fires blazing in all directions showed that the fears of the people had been allayed, and that many of them had returned to their homes.

How tired I felt that evening! for not only had I been excited all day, but I had left Mayolo's village in the morning with a heavy load on my back. Besides my revolvers, I carried a double-barreled gun, and in my bag I had fifty cartridges for revolvers, ten bullets for a long-range Enfield rifle, ten bullets for smooth-bore guns, ten steel-pointed bullets, and more than twenty pounds of small shot, buck-shot, powder, etc. In all, I carried a weight of over sixty pounds, besides my food, and my aneroids, barometers, policeman's lantern, and prismatic compass. I was so weary that I could not sleep. I resolved not to carry such big loads any more.

But my work was not yet done: in the evening I had to make astronomical observations. As I was afraid of frightening the people, I had to do this slyly. I was glad when I had finished it, but I found by my observations that we had gone directly east from Mayolo's village.

The next morning I walked from one end of the village of Mouendi to the other. The street was four hundred and forty-seven yards long, and eighteen yards broad. The soil was clay and not a blade of grass could be seen. The houses were from five to seven yards long, and from seven to ten feet broad; the height of the walls was about four feet, and the distance from the ground to the top of the roof was seven or eight feet. Back of the houses were immense numbers of plantain-trees. In the morning many of the people returned. Mayolo and Nchiengain had a long talk together. Nchiengain was fully persuaded that I could do any thing I wished; consequently, that I could make any amount of goods and beads for him. A grand palaver took place, and Mayolo began the day by making a speech. He said,

"The last moon I sent some of my people to buy salt from you Apono. You refused to sell salt, and sent word that you did not want the Oguizi to come into your country, because he brought the plague, sickness, and death. So I said to the Oguizi, 'Never mind; there is a chief in the Apono country who is my nkaga (born the same day); I will send messengers to him; he has big canoes, and I am sure he will let us cross the river with them.' Then I sent three of my nephews to you, Nchiengain, my nkaga, with beads and nice things, and I said to them, 'Go and tell Nchiengain that I am coming with the Oguizi, who is on his way to the country of the Ishogos.' You sent back your kendo, Nchiengain, with the words, 'Tell Mayolo to come with his Oguizi.' Here we are, Nchiengain, in your village, and I am sure you and your people will not slight us" (mpouguiza).

I gave to Nchiengain one shirt, six yards of prints, one coat, a red cap, one big bunch of white beads and one of red, a necklace of very large beads, files, fire-steels, spoons, knives and forks, a large looking-glass, and some other trinkets, and then called the leading men and women, and gave them presents also. This settled our friendship, for the people were pleased with the wonderful things I gave them.

The news of my untold wealth spread far and wide. People from a neighboring village, who had been very much opposed to my journey through their country, made their appearance. When Nchiengain saw them, he said, "Go away! go away! now you come because you have smelt the niva (goods and nice things). You are not afraid now."

After two or three days the people of Mouendi began to say, "How is it that two or three days ago we were so afraid of the Spirit? Now our fears are gone, and we love him. He plays with our children, and gives beads to our women." When I heard them utter these words, I said, "Apono, that is the way I travel. Those fine things that I give you are the plague I leave behind me! I bring not death, but beads; so do not be afraid of me." They replied, "Rovano! Rovano!" ("That is so!")

A few days passed away, and then the Apono and I became great friends. They began to wonder why they had been so frightened by the Ibamba (a new name given me by the Apono), and soon all the people had returned to the village. Good old Nchiengain and Mayolo had at last a jolly frolic together, and got quite tipsy with palm wine. I wish you had heard them talk. The way they were going to travel with me was something wonderful. Such fast traveling on foot you never heard of before. Tribe after tribe were to be passed by them. They were not afraid; they did not care. We were even to travel by night over the prairie, for the full moon was coming.

After a few days at Mouendi, Nchiengain with his Aponos, and Mayolo with his own people, took me farther on; but before our departure Nchiengain and the Apono went out before daylight to obtain the palm wine which had fallen into their calabashes during the night. By sunrise they were all tipsy, and Nchiengain was reeling, but he was full of enthusiasm for the journey; Mayolo also was tipsy, but not quite so far gone as his friend Nchiengain. When I saw this state of things I demolished all the mbomi (calabashes), spilling on the ground the palm wine they contained, to the great sorrow of the Aponos.

"Where is Nchiengain?" I inquired, when we were ready to start. He could not be found; and, suspecting that he was somewhere behind his hut, drinking more palm wine before starting, I went to hunt for him. The old rascal, thinking I was busy engaged in looking after my men, was quietly drinking from the mbomi itself, with his head up and his mouth wide open. Before he had time to think, I seized his calabash, and poured the contents on the ground. Poor Nchiengain! he supplicated me not to pour it all away, but to leave a little bit for him. "I will go with you at once," he said; "give me back my mug" (a mug I had given him); "oh, Spirit, give it back to me!" By this time all the villagers had gathered about us. I put the mug on the ground, and told Nchiengain's wife to come and take it; and this gave great joy to the people, who exclaimed, "Nchiengain, go quick! go quick!"

When we left I went to the rear, to see that all the porters were ahead; but old Nchiengain lagged behind, for he could not walk fast enough.

Three quarters of an hour afterward we found ourselves on the banks of a large river, the same which is described in my "Apingi Kingdom" – that kingdom being situated farther down the stream than the point at which we were now to cross. The river could not be seen from the prairie, for its banks were lined with a belt of forest trees. We found on the banks of the stream Nchiengain's big canoe waiting for us, together with some smaller ones. The large canoe was very capacious, but before all my luggage could be ferried over it was necessary to make seven trips. I sent Igala, Rebouka, and Mouitchi to the other side with the first load to keep watch. The canoe had just returned from its seventh trip, and the men were landing, when suddenly I heard the voice of Nchiengain in the woods shouting, "I am coming, Spirit! Nchiengain is coming!" It was half past four P.M. A whole day had been lost.

Not caring to take his majesty Nchiengain reeling drunk into my canoe, I jumped into it and ordered the men to push from the shore with the utmost speed. We started in good time, for we were hardly off when I began to distinguish the king's form through the woods, and when he reached the shore we were about fifty yards distant. We heard him shout "Come back! come back to fetch me;" but the louder he called the more deaf we were. "Go on, boys!" I ordered. As our backs were turned to the king, of course we could not see him. Finally we landed, and, taking my glass, I saw poor Nchiengain gesticulating on the other side, apparently in a dreadful state, thinking that I had left him. The canoe was sent back for him, and a short time afterward he was landed on our side of the river, to his great delight. Two or three times during the passage he lost his equilibrium, but he did not fall. When he joined us he was about as tipsy as when I left him in the morning.

Poor Mayolo, who had been continually tipsy since we had left his village, fell ill during the night, and a very high fever punished him for his sins.

We built our camp where we had landed. A thick wood grew on the bank of the river, and firewood was plentiful. In the evening Nchiengain was sober again, and before ten o'clock every body was fast asleep except three of my Commi men, who were on the watch. The dogs were lying asleep, and almost in the fire. Every thing now promised well, and I was anxious to hurry forward as rapidly as possible on the following day.

At a quarter past six o'clock A.M. we left our encampment, every body being perfectly sober. Soon afterward we emerged from the woods into a prairie, and passed several villages, the people of which seemed to have heard wonderful stories of my wealth. They came out, and followed me with supplies of goats and plantain, and begged Nchiengain and his people to remain with the Oguizi. In the villages they went so far as to promise several slaves to Nchiengain if he would do this. Hundreds of these villagers, while following us, gazed at me, but if I looked at them they fled in alarm. Finally, seeing that it was useless to follow, they went back, shouting to Nchiengain and to Mayolo that it was their fault if I did not stop. My porters joined them in their grumbling, for the fat goats tempted them.

About midday we halted in a beautiful wooded hollow, through which ran a little rivulet of clear water, and by its side we seated ourselves for breakfast. I was really famished. After spending an hour in eating and resting, we started again. When we came out of the wood we saw paths leading in different directions, one going directly east to several Apono villages. Nchiengain was opposed to our passage through them, and therefore we struck a path leading in a more southerly direction, or S.S.E. by compass. For three hours we journeyed over an undulating prairie dotted with clumps of woods, and then crossed a prairie called Matimbié irimba (the prairie of stones), the soil of which was covered with little stones containing a good deal of iron. The men suffered greatly as they stepped upon them.

CHAPTER XIX

RUMORS OF WAR. – THROUGH A BURNING PRAIRIE. – IMMINENT PERIL. – NARROW ESCAPE FROM A HORRIBLE DEATH. – A LONELY NIGHT-WATCHWar began to loom up as we reached the southeast end of the Matimbié irimba. We came to a village called Dilolo, the path we were following leading directly to it, and as we approached we found that the place had been barricaded, and that it was guarded outside by all its fighting men. On the path charms had been placed, to frighten away the Aponos. The men were armed with spears, bows and arrows, and sabres. When we came near earshot, having left the path with the intention of passing by the side of the village, they vented bitter curses against Nchiengain for bringing the Oguizi into their country – "the Oguizi who comes with the eviva (plague) into villages," they shouted. "Do not come near us; do not try to enter our village, for there will be war!" The war-drums were beaten, and the men advanced and retired before us, spear in hand, as if to drive us away, for they thought we had come too near. We marched forward, nevertheless. So long as the Apono porters did not show the white feather, I felt safe; they also had their spears and their bows, and my men held their guns in readiness. Suddenly fires appeared in different parts of the prairie. The people of Dilolo had set fire to the grass, hoping that we might perish in the flames. The fire spread with fearful rapidity, but we soon came to a place where our path made a turn by the village, and we reached the rear of the place. At that moment we observed a body of villagers moving in our direction, evidently intending to stop our progress. Presently two poisoned arrows were shot at us. I thought we were going to have a fight, but ordered my men to keep cool, and not to fire. Nchiengain walked all along the line to cheer up his men, and shouted that "Nchiengain's people were not afraid of war," but at the same time he begged me not to fire a gun unless some of our people were hit with the arrows.

We continued our march, keeping close together, so that we might help each other in case of need. My men were outside the path, between Nchiengain and the Dilolo people, with their guns ready to fire when I gave the word. The villagers, mistaking our forbearance for fear, became bolder, and the affair was coming to a crisis. A warrior, uttering a fierce cry of battle, came toward us, and, with his bow bent, stood a few yards in front of Rapelina, threatening to take his life. I could see the poison on the barbed arrow. My eyes were fixed upon the fellow, and I felt very much like sending a bullet through his head. Plucky Rapelina faced his enemy boldly, and, looking him fiercely in the face, uttered the war cry of the Commi, and, lowering the muzzle of his gun, advanced two steps, and shouted in the Apono language that if the Dilolo did not put down his bow he would be a dead man before he could utter another word. By this time all my Commi men had come up, with the muzzle of their guns pointing toward the Dilolo, awaiting my order to fire. The bow fell from the warrior's hand, and he retreated.

Nchiengain behaved splendidly. He began to curse the Dilolo people, and said to them, "You will hear of me one of these days;" and my Aponos threw down their loads and got ready to fight.

"Let us hurry," I said to the men; "don't you see the country is getting into a blaze of fire? We must get out of it."

I fired a gun after we had passed the village, and the inhabitants were terrified at the noise. Nchiengain was furious, and again shouted to the enemy, "You will see that I am not a boy, and that my name is Nchiengain!"

The discomfited warriors of Dilolo gradually left us, probably thinking that the fire, so rapidly spreading, would do the work they could not perform; and, indeed, while we had escaped a conflict through our good common sense, we were now exposed to a far greater danger. The fire was gaining fearfully. The whole country seemed to be in a blaze. Happily, the wind blew from the direction in which we were going; still the flames were fast encircling us, and there was but one break in the circuit it was making. I shouted, "Hurry, boys! hurry! for if we do not get there in time, we shall have to go back, and then we must fight, for we will have to get into the village of Dilolo." So we pressed forward with the utmost speed, and finally our road lay between two walls of fire, but the prairie was clear of flames ahead. Although the walls of fire were far apart, they were gaining upon us. "Hurry on, boys!" I exclaimed; "hurry on!" We walked faster and faster, for the smoke was beginning to reach us. The fire roared as it went through the grass, and left nothing but the blackened ground behind it. We began to feel the heat. The clear space was getting narrower and narrower. I turned to look behind, and saw the people of Dilolo watching us. Things were looking badly. Were we going to be burned to death? Again looking back toward Dilolo, I saw that the fires had united, and that the whole country lying between ourselves and Dilolo was a sheet of flame.

Onward we sped, Nchiengain exhorting his men to hurry. We breathed the hot air, but happily there was still an open space ahead. We came near it, and felt relieved. At last we reached it, and a wild shout from Nchiengain, the Aponos, and my Commi rent the air. We were saved, but nearly exhausted.

I said to my Commi men, "Are we not men? There is no coming back after this! Boys, onward to the River Nile!" They all shouted in reply, "We must go forward; we are going to the white man's country."

Between four and five o'clock we came to another wood, in the midst of which was a cool spring of water. We encamped there for the night, and not far in the distance on the prairie we could see the smoke coming out of a cluster of Apono villages. They dreaded our approach. In the silence of the twilight, the wind from the mountains brought to us the cries of the people. We could hear the shrieks and the weeping of the women, and the beating of the war-drums. Afterward the people came within speaking distance, and shouted to us, "Oh, Nchiengain, why have you brought this curse upon us? We do not want the Oguizi in our country, who brings the plague with him. We do not want to see the Ibamba. The Ishogo are all dead; the Ashango have all left; there is nothing but trees in the forest. Go back! go back!" They yelled and shouted till about ten o'clock, and then all became silent, and soon afterward my people were asleep by the fires which they had lighted. They all suffered from sore feet. Igala, Mouitchi, and Rapelina were to keep watch with me, while my other Commi men were resting; but they, too, after a while, went to sleep. Even our poor dogs were tired, and were also sound asleep.

I stood all alone, watching over the whole camp, so anxious that I could not sleep. Things did look dark indeed. A most terrible dread of me had taken possession of the people. Something had to be done to allay their fears, or my journey would come to an end.

How quiet every thing was! The rippling of the water coming from the little brook sounded strangely in the midst of the silent night. I looked at the strange scene around me. Each of my men had his gun upon his arm, but I thought of how useless the weapons would be in the hands of men so weary, and sunk in deep sleep. If, that night, any one of you could have been there, you would have seen Paul Du Chaillu leave the camp and the woods, and then have seen him all alone upon the prairie, standing like a statue, no one by him, his gun in one hand, his revolvers hung by his side. The stars shone beautifully above his head, as if to cheer him in his loneliness, for lonely and sad enough he felt. Then, with an anxious feeling, he looked through his spy-glass in the direction of the Apono villages to see if any thing was going on there. No. All there, too, was silent as death.

At three o'clock in the morning I awakened Igala and some of my Commi boys, and told them to keep watch while I tried to get a little sleep.

CHAPTER XX

A DEPUTATION FROM THE VILLAGE. – A PLAIN TALK WITH THEM. – A BEAUTIFUL AND PROSPEROUS TOWN. – CHEERFUL CHARACTER OF THE PEOPLE. – MORE OBSERVATIONSBefore daylight I arose, and again went out upon the prairie, but saw no one there from the Apono villages, and heard no war-drumming. After a while a deputation of three men came from the village to Nchiengain, and said, "Why have you brought this Oguizi to us? He will give us the eviva."

"No," said Nchiengain; "months ago the eviva was in the country. I myself got it; people died of it, and others got over it. The eviva has worked where it pleased, and gone where it pleased, and that when the Spirit had never made his appearance. He has nothing to do with the eviva. Go and tell your people that Nchiengain said so, and that the Spirit has only been a few days in our country." The men went off without seeing me, for Nchiengain was afraid they might be frightened.