полная версия

полная версияElkan Lubliner, American

Benson made a circular gesture with his right hand.

"I could get lots of partners with big money, Mr. Lubliner," he said, "but why should I divide my profits? Am I right or wrong?"

"Well, that depends how you are looking at it," Elkan said.

"I am looking at it from the view of a business man, Mr. Lubliner," Benson rejoined. "Here I got a proposition which I am going to put on – a show of idees – a big production, understand me; which if Ryan & Bernbaum makes from their 'Diners Out' a hundred thousand dollars, verstehst du, I could easily make a hundred and fifty thousand! And yet, Mr. Lubliner, all I invest is five thousand dollars and five thousand more which I am making a loan at a bank."

"Which bank?" Elkan asked – so quickly that Benson almost jumped in his seat.

"I – I didn't decide which bank yet," he replied. "You see, Mr. Lubliner, I got accounts in three banks. First I belonged to the Fifteenth National Bank. Then they begged me I should go in the Minuit National Bank. All right. I went in the Minuit National Bank. H'afterward Sam Feder comes to me and says: 'Benson,' he says, 'you are an old friend from mine,' he says. 'Why do you bother yourself you should go into this bank and that bank?' he says. 'Why don't you come to my bank?' he says, 'and I would give you all the money you want.' So you see, Mr. Lubliner, it is immaterial to me which bank I get my money from."

Again he passed his jewelled fingers through his hair.

"No, Mr. Lubliner," he announced after a pause, "my own brother even I wouldn't give a look-in."

Elkan made no reply. As a result of Benson's gesture he was busy estimating the value of eight and a quarter carats at eighty-seven dollars and fifty cents a carat.

"Because," Benson continued, "the profits is something you could really call enormous! If you got the time I would like to show you a few figures."

"I got all evening," Elkan answered, whereat Benson pulled from his waistcoat pocket a fountain pen ornamented with gold filigree.

"First," he said, "is the costumes."

And therewith he plunged into a maze of calculation that lasted for nearly an hour. Moreover, at the end of that period he entered into a new series of figures, tending to show that by the investment of an additional five thousand dollars the profits could be increased seventy-five per cent.

"But I'm satisfied to invest my ten thousand," he said, "because five thousand is my own and the other five thousand I could get easy from the Kosciuscko Bank, whereas the additional five thousand I must try to interest somebody he should invest it with me. And so far as that goes I wouldn't bother myself at all."

"You're dead right," Elkan said by way of making himself agreeable, whereat Benson grew crimson with chagrin.

"Sure I'm dead right," he said; "and if you and Mrs. Lubliner would come down to my office in the Siddons Theatre Building to-morrow night, eight o'clock, I would send one of my associates round with you and he will get you tickets for the 'Diners Out,' understand me; and then you would see for yourself what a big house they got there. Even on Monday night they turn 'em away!"

"I'm much obliged to you," Elkan replied. "I'm sure Mrs. Lubliner and me would enjoy it very much."

"I'm sorry for you if you wouldn't," Benson retorted; "and that there 'Diners Out' ain't a marker to the show I'm putting on, Mr. Lubliner – which you can see for yourself, a business proposition, which pans out pretty near two hundred thousand dollars on a fifteen-thousand-dollar investment, is got to be right up to the mark. Ain't it?"

"I thought you said ten thousand dollars was the investment," Elkan remarked.

"I did," Benson replied with some heat; "but if some one comes along and wants to invest the additional five thousand dollars I wouldn't turn him down, Mr. Lubliner."

He rose to his feet to join the pinocle players in the dining room.

"So I hope you enjoy the show to-morrow night," he added as he strolled away.

From six to eight every evening Max Merech underwent a gradual transformation, for six o'clock was the closing hour at Polatkin, Scheikowitz & Company's establishment, while eight marked the advent of the Sarasate Trio at the Café Román, on Delancey Street. Thus, at six, Max Merech was an assistant cutter; and, indeed, until after he ate his supper he still bore the outward appearance of an assistant cutter, though inwardly he felt a premonitory glow. After half-past seven, however, he buttoned on a low, turned-down collar with its concomitant broad Windsor tie, and therewith he assumed his real character – that of a dilettante.

At the Café Román each evening he specialized on music; but with the spirit of the true dilettante he neglected no one of the rest of the arts, and was ever to be found at the table next to the piano, a warm advocate of the latest movement in painting and literature, as well as an appreciative listener to the ultramodern music discoursed by the Sarasate Trio.

"If that ain't a winner I ain't no judge!" he said to Boris Volkovisk, the pianist, on the evening of the conversation with Elkan set forth above. He referred to a violin sonata of Boris' own composition which the latter and Jacob Rekower, the violinist, had just concluded.

Boris smiled and wiped away the perspiration from his bulging forehead, for the third movement of the sonata, marked in the score Allegro con fuoco, had taxed even the technic of its composer.

"A winner of what?" Boris asked – "money? Because supposing a miracle happens that somebody would publish it nobody buys it."

Max nodded his head slowly in sympathetic acquiescence.

"But anyhow you ain't so bad off like some composers," he said. "You've anyhow got a good musician to play your stuff for you."

He smiled at Jacob Rekower, who plunged his hands into his trousers pockets and shrugged deprecatingly.

"Sure, I know," Rekower said; "and if we play too much good stuff Marculescu raises the devil with us we should play more popular music."

He spat out the words "popular music" with an emphasis that made a Tarrok player at the next table jump in his seat.

"Nu," said the latter as the deal passed, "what is the matter with popular music? If it wouldn't be for writing popular music, understand me, many a decent, respectable composer would got to starve!"

He turned his chair round and abandoned the card game the better to air his views on popular music.

"Furthermore," he said, "I know a young feller by the name Milton Jassy which last year he makes two thousand dollars already from syncopating Had gadyo and calling it the "Wildcat Rag," and this year he is writing the music for a new show and I bet yer the least he makes out of it is five thousand dollars."

"Yow! Five thousand dollars!" Merech exclaimed. "Such people you hear about, but you oser see 'em."

"Don't you?" said the Tarrok player, drawing a cardcase from his breast pocket. "Well, you see one now."

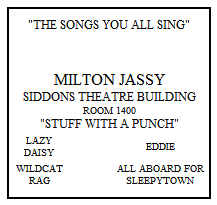

He laid face upward on the table a card which read:

For a brief interval Volkovisk, Rekower, and Merech regarded Jassy's card in silence.

"Well," Merech said at last, "what of it?"

Jassy shrugged and waved his hand significantly.

"Nothing of it," he said, "only your friend there is knocking popular music; and though I admit that I didn't got to go to the Wiener conservatory so as I could write popular music exactly, y'understand, still I could write sonatas and trios and quartets and even concerti and symphonies till I am black in the face already and I couldn't pay my laundry bill even."

For answer Volkovisk turned to the piano and seized from the pile of music a blue-covered volume. It was the violin sonata of Richard Strauss, and handing the violin part to Rekower he seated himself on the stool. Then with a premonitory nod to Rekower he struck the opening chords, and for more than ten minutes Jassy and Merech sat motionless until the first movement was finished.

"When Strauss wrote that he could oser pay his laundry bill either," Volkovisk said, rising from the stool. He sat down wearily at the table and lit a cigarette.

"So you see," he began, "Richard Strauss – "

"Richard Strauss nothing!" cried an angry voice at his elbow. "If you want to practise, practise at home. I pay you here to play for my customers, not for yourselves, Volkovisk; and once and for all I am telling you you should cut out this nonsense and spiel a little music once in a while."

It was the proprietor, Marculescu, who spoke, and Volkovisk immediately seated himself at the piano. This time he took from the pile of music three small sheets, one of which he placed on the reading desk and the other on Rekower's violin stand. After handing the other sheet to the 'cellist he plunged into a furious rendition of "Wildcat Rag."

In the front part of the café a group of men and women, whose clothes and manners proclaimed them to be slummers from the upper West Side, broke into noisy applause as the vulgar composition came to an end, and in the midst of their shouting and stamping Jassy rose trembling from his seat. He slunk between tables to the door, while Volkovisk began a repetition of the number, and it was not until he had turned the corner of the street and the melody had ceased to sound in his ears that he slackened his pace. When he did so, however, a friendly hand fell on his shoulder and he turned to find Max Merech close behind him.

"Nu, Mr. Jassy," Max said, "you shouldn't be so broke up because you couldn't write so good as Richard Strauss."

Jassy stood still and looked Max squarely in the eye.

"That's just the point," he said in hollow tones. "Might I could if I tried; but I am such an Epikouros that I don't want to try. I would sooner make money out of rubbish than be an artist like Volkovisk."

Max shrugged and elevated his eyebrows.

"A man must got to live," he said as he seized Jassy's arm and began gently to propel him back to the Café Román.

"Sure, I know," Jassy said; "but living ain't all having good clothes to wear and good food to eat. Living for an artist like Volkovisk is composing music worthy of an artist. Aber what do I do, Mister – "

"Merech," Max said.

"What do I do, Mr. Merech?" Jassy continued. "I am all the time throwing away my art in the streets with this rotten stuff I am composing."

"Well, I tell you," Max said after they had reëntered the café and had seated themselves at a table remote from the piano, "composing music is like manufacturing garments, Mr. Jassy. Some one must got to cater to the popular-price trade and only a few manufacturers gets to the point where they make up a highgrade line for the exclusive retailers. Ain't it?"

Jassy nodded as the waiter brought the cups of coffee.

"Now you take me, for instance," Max continued. "Once I worked by B. Gans, which I assure you, Mr. Jassy, it was a pleasure to handle the goods in that place. What an elegant line of silks and embroidery they got it there! Believe me, Mr. Jassy, every day I went to work there like I would be going to a wedding already, such a beautiful goods they made it! Aber now I am working by a popular-price concern, Mr. Jassy, which, you could take it from me, the colors them people puts together in one garment gives me the indigestion already!"

Again Jassy nodded sympathetically.

"And why did I make a change?" Max went on. "Because them people pays me seven dollars a week more as B. Gans, Mr. Jassy; and though art is art, understand me, seven dollars a week ain't to be coughed at neither."

For a few minutes Jassy sipped his coffee in silence.

"That's all right, too," he said; "but with garments you could make just so much money manufacturing a highgrade line as you could if you are making a popular-price line."

Max nodded sapiently.

"I give you right there," he agreed, "and that's because the manufacturer of the highgrade line does business in the same way as the popular-price concern. Aber you take the composer of highgrade music and all he does is compose. He's too proud to poosh it, Mr. Jassy; whereas the feller what composes popular music he's just the same like the feller what manufacturers a popular-price line of garments – he not only manufacturers his line but he pooshes it till he gets a market for it."

"There ain't no market for a highclass line of music," Jassy said hopelessly.

"Why ain't there?" Max demanded. "Did you ever try to market a symphony? Did Volkovisk ever try to get anybody with money interested in his stuff? No, sirree, sir! All that feller does is to play it to a lot of Schnorrers like me, which no matter how much we like his work we couldn't help him none. Now you take your own case, for instance. You told us a few minutes ago you are writing some music for a new show. Now, if you wouldn't mind my asking, who is putting in the capital for that show?"

"Well," Jassy replied, "a feller called Benson is putting it in and part of the capital is from his own money and the rest he borrows."

"Just like a new beginner would do in the garment business," Max commented. "Aber who does he borrow it from? A bank maybe – what?"

"Some he gets from a bank," Jassy replied, "and the rest is he trying to raise elsewheres. To-night he tells me he is getting an introduction to a business man which he hopes to lend from him five oder ten thousand dollars."

"Five oder ten thousand dollars!" Max cried. "Shema beni. For five thousand dollars Volkovisk could publish all the music he ever wrote and give a whole lot of recitals in the bargain. One thousand dollars would be enough even."

"That I wouldn't deny at all," Jassy rejoined. "Aber who would you find stands willing he should invest in Volkovisk's music a thousand dollars? Would he ever get back his thousand dollars even, let alone any profits?"

"It's a speculation, I admit," Max commented; "but you take Richard Strauss, for instance, and if some feller would staked Strauss to a thousand dollars capital when he needed it, understand me, not alone he would got his money back but if we would say, for example, the thousand dollars represents a ten-per-cent interest in Strauss' business, to-day yet the feller would be worth his fifty thousand dollars, because everybody knows what a big success Strauss made. Actually the feller must got orders at least six months ahead. Why for one song alone they pay him a couple thousand dollars!"

"Well," Jassy asked, "if you feel there's such a future in it why don't you raise a thousand dollars and finance Volkovisk?"

Max laughed aloud.

"Me – I couldn't raise nothing," he said; "aber you – you are feeling sore at yourself because you are writing popular stuff. Here's a chance for you to square yourself with your art. Why don't you help Volkovisk out? All you got to do is to find out who is loaning this here Benson the ten thousand dollars and get him to stake Volkovisk to a thousand."

Jassy tapped the table with his fingers.

"For that matter I could say the same thing to you," he declared. "You consider Volkovisk's talent so high as a business proposition, Merech, why don't you get some business man interested – one of your bosses, for instance?"

He rose from his chair as he spoke and placed ten cents on the table as his share of the evening's expenses.

"Think it over," he said; and long after he had closed the door behind him Max sat still with his hands in his trousers pocket and pondered the suggestion.

"After all," he mused as Marculescu began to turn out the lights one by one, "why shouldn't I – the very first thing in the morning?"

It was not, however, until Polatkin and Scheikowitz had gone out to lunch the following day, leaving Elkan alone in the office, that Max could bring his courage to the sticking point; and so fearful was he that he might regret his boldness before it was too late, he fairly ran from the cutting room to the office and delivered his preparatory remarks in the outdoor tones of a political spellbinder.

"Mr. Lubliner," he cried, "could I speak to you a few words something?"

Elkan rose and slammed the door.

"Say, lookyhere, Merech," he said, "if you want a raise don't let the whole factory know about it, otherwise we would be pestered to death here. Remember, also," he continued as he sat down again, "you are only working for us a few weeks – and don't go so quick as all that."

"What d'ye mean, a raise?" Max asked. "I ain't said nothing at all about a raise. I am coming to see you about something entirely different already."

Elkan looked ostentatiously at his watch.

"I ain't got too much time, Merech," he said.

"Nobody's got too much time when it comes to fellers asking for raises, Mr. Lubliner," Max retorted; "aber this here is something else again, as I told you."

"Well, don't beat no bushes round, Merech!" Elkan cried impatiently. "What is it you want from me?"

"I want from you this," Max began huskily: "Might you know Tschaikovsky maybe oder Rimsky-Korsakoff."

"Tschaikovsky I never heard of," Elkan replied, "nor the other concern neither. Must be new beginners in the garment business – ain't it?"

"They never was in the garment business, so far as I know," Max continued; "aber they made big successes even if they wasn't, because all the money ain't in the garment business, Mr. Lubliner, and Tschaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakoff, even in the old country, made so much money they lived in palaces yet. Once when I was a boy already, Tschaikovsky comes to Minsk and they got up a parade for him – such a big Macher he was!"

"I don't doubt your word for a minute, Merech; aber what is all this got to do mit me?"

"It ain't got nothing to do with you, Mr. Lubliner," Max declared – "only I got a friend by the name Boris Volkovisk, and believe me or not, Mr. Lubliner, in some respects Tschaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakoff could learn from that feller, because, you could take it from me, Mr. Lubliner, there's some passages in the Fifth Symphony, understand me, which I hate to say it you could call rotten!"

Elkan stirred uneasily in his chair.

"I don't know what you are talking about at all," he said.

"I am talking about this," Max replied; and therewith he began to explain to Elkan the aspirations and talent of Boris Volkovisk and his – Max' – scheme for their successful development. For more than half an hour he unfolded a plan by which one thousand dollars might be judiciously expended so as to secure the maximum benefit to Volkovisk's career – a plan that during the preceding two years Volkovisk and he had thoroughly discussed over many a cup of coffee in Marculescu's café. "And so you see, Mr. Lubliner," he concluded, "it's a plain business proposition; and if you was to take for your thousand dollars, say, for example, a one-tenth interest in the business Volkovisk expects to do, understand me, you would get a big return for your investment."

Elkan lit a cigar and puffed away reflectively before speaking.

"Nu," he said at last; "so that is what you wanted to talk to me about?"

Max nodded.

"Well, then, all I could say is," Elkan went on, "you are coming to the wrong shop. A business proposition like that is for a banker, which he is got so much money he don't know what to do with it, Merech."

Max' face fell and he turned disconsolately away.

"At the same time, Max," Elkan added, "I ain't feeling sore that you come to me with the proposition, understand me. The trouble ain't with you that you got such an idee, Max; the trouble is with me that I couldn't see it. It's like a feller by the name Dalzell, a buyer for Kammerman's store, says to me this morning. 'Lubliner,' he says, 'I couldn't afford to take no chances buying highgrade garments from a feller that is used to making a popular-price line,' he says, 'because no matter how well equipped your factory would be the trouble is a popular-price manufacturer couldn't think big enough to turn out expensive garments. To such a manufacturer goods at two dollars a yard is the limit, and goods at ten dollars a yard he couldn't imagine at all. And even if he could induce himself to use stuff at ten dollars a yard, y'understand, it goes against him to be liberal with such high-priced goods, so he skimps the garment.'"

He blew a great cloud of smoke as a substitute for a sigh.

"And Dalzell was right, Max," he concluded. "You couldn't expect that a garment manufacturer like me is going to got such big idees as investing a thousand dollars in a highgrade scheme like yours. With me a thousand dollars means so many yards piece goods, so many sewing machines or a week's payroll; aber it don't mean giving a musician a show he should compose highgrade music. I ain't educated up to it, Max; so I wish you luck that you should raise the money somewheres else."

When M. Sidney Benson entered his office in the Siddons Theatre Building late that afternoon he found Jassy seated at his desk in the mournful contemplation of some music manuscript.

"Nu, Milton," Benson cried, "you shouldn't look so rachmonos. I surely think I got 'em coming!"

"You think you got 'em coming!" Jassy repeated with bitter emphasis. "You said that a dozen times already – and always the feller wasn't so big a sucker like he looked!"

"That was because I didn't work it right," Benson replied. "This time I am making out to do the feller a favour by letting him in on the show, and right away he becomes interested. His name is Elkan Lubliner, a manufacturer by cloaks and suits, and to-night he is coming down with his wife yet, and you are going to take 'em round to the 'Diners Out.'"

"I am going to the 'Diners Out' mit 'em?" Milton ejaculated with every inflection of horror and disgust.

"Sure!" Benson replied cheerfully. "Six dollars it'll cost us, because Ryan pretty near laughs in my face when I asked him for three seats. But never mind, Milton, it'll be worth the money."

"Will it?" Jassy retorted. "Well, not for me, Mr. Benson. Why, the last time I seen that show I says I wouldn't sit through it again for a hundred dollars."

"A hundred dollars is a lot of money, Milton," Benson said. "Aber I think if you work it right you will get a hundred times a hundred dollars before we are through, on account I really got this feller going. So you should listen to me and I would tell you just what you want to say to the feller between the acts."

Therewith Benson commenced to unfold a series of "talking points" which he had spent the entire day in formulating; and, as he proceeded, Jassy's eyes wandered from the title page of the manuscript music inscribed "Opus 47 – Trio in G moll," and began to glow in sympathy with Benson's well-laid plan.

"There's no use shilly-shallying, Milton," Benson concluded. "The season is getting late, and if we're ever going to put on that show now is the time."

Milton nodded eagerly.

"Aber why don't you take 'em to the show yourself, Mr. Benson?" he asked hopefully. "Because, not to jolly you at all, Mr. Benson, I must got to say it you are a wonderful talker."

Benson shrugged his shoulders and smiled weakly.

"I am a wonderful talker, I admit," he agreed; "but I got a hard face, Milton, whereas you, anyhow, look honest. So you should meet me at Hanley's afterward, understand me, and we would try to close the deal there and then."

He dug his hand into his trousers pocket and produced a modest roll of bills, from which he detached six dollars.

"Here is the money," he added, "and you should be here to meet them people at eight o'clock sharp."

On the stroke of eight Milton Jassy returned to Benson's office in the Siddons Theatre Building and again seated himself at his desk in front of the pile of manuscript music. This time, however, he brushed aside the title page of his Opus 47 and spread out an evening paper to beguile the tedium of awaiting Benson's "prospects." Automatically he turned to the department headed Music and Musicians, and at the top of the column his eye fell on the following item: