полная версия

полная версияThe Bābur-nāma

It is necessary to enumerate the items of the Compilation here as they are arranged in Kehr’s autograph Codex, because that codex (still in London) may not always be accessible,23 and because the imprint does not obey its model, but aims at closer agreement of the Bukhara Compilation with Ilminski’s gratefully acknowledged guide —The Memoirs of Baber. Distinction in commenting on the Bukhara and the Kasan versions is necessary; their discrepancy is a scene in the comedy of errors.

Outline of the History of the CompilationAn impelling cause for the production of the Bukhara compilation is suggested by the date 1709 at which was finished the earliest example known to me. For in the first decade of the eighteenth century Peter the Great gave attention to Russian relations with foreign states of Central Asia and negociated with the Khan of Bukhara for the reception of a Russian mission.24 Political aims would be forwarded if envoys were familiar with Turki; books in that tongue for use in the School of Oriental Languages would be desired; thus the Compilation may have been prompted and, as will be shown later, it appears to have been produced, and not merely copied, in 1709. The Mission’s despatch was delayed till 1719;25 it arrived in Bukhara in 1721; during its stay a member of its secretariat bought a Compilation MS. noted as finished in 1714 and on a fly-leaf of it made the following note: —

“I, Timur-pulad son of Mirza Rajab son of Pay-chin, bought this book Babur-nama after coming to Bukhara with [the] Russian Florio Beg Beneveni, envoy of the Padshah … whose army is numerous as the stars… May it be well received! Amen! O Lord of both Worlds!”

Timur-pulad’s hope for a good reception indicates a definite recipient, perhaps a commissioned purchase. The vendor may have been asked for a history of Babur; he sold one, but “Babur-nama” is not necessarily a title, and is not suitable for the Compilation; by conversational mischance it may have seemed so to the purchaser and thus have initiated the mistake of confusing the “Bukhara Babur-nama” with the true one.

Thus endorsed, the book in 1725 reached the Foreign Office; there in 1737 it was obtained by George Jacob Kehr, a teacher of Turki, amongst other languages, in the Oriental School, who copied it with meticulous care, understanding its meaning imperfectly, in order to produce a Latin version of it. His Latin rendering was a fiasco, but his reproduction of the Arabic forms of his archetype was so obedient that on its sole basis Ilminski edited the Kasan Imprint (1857). A collateral copy of the Timur-pulad Codex was made in 1742 (as has been said).

In 1824 Klaproth (who in 1810 had made a less valuable extract perhaps from Kehr’s Codex) copied from the Timur-pulad MS. its purchaser’s note, the Auzbeg?(?) endorsement as to the transfer of the “Kamran-docket” and Babur’s letter to Kamran (Mémoires relatifs à l’Asie Paris).

In 1857 Ilminski, working in Kasan, produced his imprint, which became de Courteille’s source for Les Mémoires de Baber in 1871. No worker in the above series shews doubt about accepting the Compilation as containing Babur’s authentic text. Ilminski was in the difficult position of not having entire reliance on Kehr’s transcription, a natural apprehension in face of the quality of the Latin version, his doubts sum up into his words that a reliable text could not be made from his source (Kehr’s MS.), but that a Turki reading-book could – and was. As has been said, he did not obey the dual plan of the Compilation Kehr’s transcript reveals, this, perhaps, because of the misnomer Babur-nama under which Timur-pulad’s Codex had come to Petrograd; this, certainly, because he thought a better history of Babur could be produced by following Erskine than by obeying Kehr – a series of errors following the verbal mischance of 1725. Ilminski’s transformation of the items of his source had the ill result of misleading Pavet de Courteille to over-estimate his Turki source at the expense of Erskine’s Persian one which, as has been said, was Ilminski’s guide – another scene in the comedy. A mischance hampering the French work was its falling to be done at a time when, in Paris 1871, there can have been no opportunity available for learning the contents of Ilminski’s Russian Preface or for quiet research and the examination of collateral aids from abroad.26

The Author of the CompilationThe Haidarabad Codex having destroyed acquiescence in the phantasmal view of the Bukhara book, the question may be considered, who was its author?

This question a convergence of details about the Turki MSS. reputed to contain the Babur-nama, now allows me to answer with some semblance of truth. Those details have thrown new light upon a colophon which I received in 1900 from Mr. C. Salemann with other particulars concerning the “Senkovski Babur-nama,” this being an extract from the Compilation; its archetype reached Petrograd from Bukhara a century after Kehr’s [viz. the Timur-pulad Codex]; it can be taken as a direct copy of the Mulla’s original because it bears his colophon.27 In 1900 I accepted it as merely that of a scribe who had copied Senkovski’s archetype, but in 1921 reviewing the colophon for this Preface, it seems to me to be that of the original autograph MS. of the Compilation and to tell its author’s name, his title for his book, and the year (1709) in which he completed it.

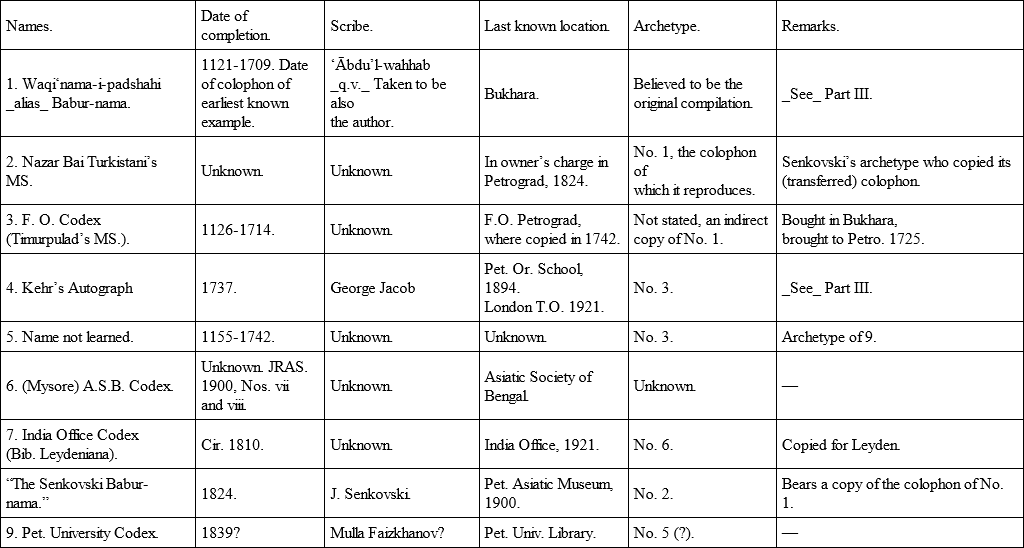

Table of Bukhara reputed-Babur-nama MSS. (Waqi‘nama-i-padshahi?).

Senkovski brought it over from his archetype; Mr. Salemann sent it to me in its original Turki form. (JRAS. 1900, p. 474). Senkovski’s own colophon is as follows: —

“J’ai achevé cette copie le 4 Mai, 1824, à St. Petersburg; elle a éte faite d’àpres un exemplaire appartenant à Nazar Bai Turkistani, négociant Boukhari, qui etait venu cette année à St. Petersburg. J. Senkovski.”

The colophon Senkovski copied from his archetype is to the following purport: —

“Known and entitled Waqi‘nama-i-padshahi (Record of Royal Acts), [this] autograph and composition (bayad u navisht) of Mulla ‘Abdu’l-wahhāb the Teacher, of Ghaj-davan in Bukhara – God pardon his mistakes and the weakness of his endeavour! – was finished on Monday, Rajab 5, 1121 (Aug. 31st, 1709).– Thank God!”

It will be observed that the title Waqi‘nama-i-padshahi suits the plan of dual histories (of Babur and Humayun) better than does the “Babur-nama” of Timur-pulad’s note, that the colophon does not claim for the Mulla to have copied the elder book (1494-1530) but to have written down and composed one under a differing title suiting its varied contents; that the Mulla’s deprecation and thanks tone better with perplexing work, such as his was, than with the steadfast patience of a good scribe; and that it exonerates the Mulla from suspicion of having caused his compilation to be accepted as Babur’s authentic text. Taken with its circumstanding matters, it may be the dénoument of the play.

Chapter IV.

THE LEYDEN AND ERSKINE MEMOIRS OF BABER

The fame and long literary services of the Memoirs of Baber compel me to explain why these volumes of mine contain a verbally new English translation of the Babur-nama instead of a second edition of the Memoirs. My explanation is the simple one of textual values, of the advantage a primary source has over its derivative, Babur’s original text over its Persian translation which alone was accessible to Erskine.

If the Babur-nama owed its perennial interest to its valuable multifarious matter, the Memoirs could suffice to represent it, but this it does not; what has kept interest in it alive through some four centuries is the autobiographic presentment of an arresting personality its whole manner, style and diction produce. It is characteristic throughout, from first to last making known the personal quality of its author. Obviously that quality has the better chance of surviving a transfer of Babur’s words to a foreign tongue when this can be effected by imitation of them. To effect this was impracticable to Erskine who did not see any example of the Turki text during the progress of his translation work and had little acquaintance with Turki. No blame attaches to his results; they have been the one introduction of Babur’s writings to English readers for almost a century; but it would be as sensible to expect a potter to shape a vessel for a specific purpose without a model as a translator of autobiography to shape the new verbal container for Babur’s quality without seeing his own. Erskine was the pioneer amongst European workers on Baburiana – Leyden’s fragment of unrevised attempt to translate the Bukhara Compilation being a negligible matter, notwithstanding friendship’s deference to it; he had ready to his hand no such valuable collateral help as he bequeathed to his successors in the Memoirs volume. To have been able to help in the renewal of his book by preparing a second edition of it, revised under the authority of the Haidarabad Codex, would have been to me an act of literary piety to an old book-friend; I experimented and failed in the attempt; the wording of the Memoirs would not press back into the Turki mould. Being what it is, sound in its matter and partly representative of Babur himself, the all-round safer plan, one doing it the greater honour, was to leave it unshorn of its redundance and unchanged in its wording, in the place of worth and dignity it has held so long.

Brought to this point by experiment and failure, the way lay open to make bee-line over intermediaries back to the fountain-head of re-discovered Turki text preserved in the Haidarabad Codex. Thus I have enjoyed an advantage no translator has had since ‘Abdu’r-rahim in 1589.

Concerning matters of style and diction, I may mention that three distinct impressions of Babur’s personality are set by his own, Erskine’s and de Courteille’s words and manner. These divergencies, while partly due to differing textual bases, may result mainly from the use by the two Europeans of unsifted, current English and French. Their portrayal might have been truer, there can be no doubt, if each had restricted himself to such under-lying component of his mother-tongue as approximates in linguistic stature to classic Turki. This probability Erskine could not foresee for, having no access during his work to a Turki source and no familiarity with Turki, he missed their lessoning.

Turki, as Babur writes it – terse, word-thrifty, restrained and lucid, – comes over neatly into Anglo-Saxon English, perhaps through primal affinities. Studying Babur’s writings in verbal detail taught me that its structure, idiom and vocabulary dictate a certain mechanism for a translator’s imitation. Such are the simple sentence, devoid of relative phrasing, copied in the form found, whether abrupt and brief or, ranging higher with the topic, gracious and dignified – the retention of Babur’s use of “we” and “I” and of his frequent impersonal statement – the matching of words by their root-notion – the strict observance of Babur’s limits of vocabulary, effected by allotting to one Turki word one English equivalent, thus excluding synonyms for which Turki has little use because not shrinking from the repeated word; lastly, as preserving relations of diction, the replacing of Babur’s Arabic and Persian aliens by Greek and Latin ones naturalized in English. Some of these aids towards shaping a counterpart of Turki may be thought small, but they obey a model and their aggregate has power to make or mar a portrait.

(1) Of the uses of pronouns it may be said that Babur’s “we” is neither regal nor self-magnifying but is co-operative, as beseems the chief whose volunteer and nomad following makes or unmakes his power, and who can lead and command only by remittent consent accorded to him. His “I” is individual. The Memoirs varies much from these uses.

(2) The value of reproducing impersonal statements is seen by the following example, one of many similar: – When Babur and a body of men, making a long saddle-journey, halted for rest and refreshment by the road-side; “There was drinking,” he writes, but Erskine, “I drank”; what is likely being that all or all but a few shared the local vin du pays.

(3) The importance of observing Babur’s limits of vocabulary needs no stress, since any man of few words differs from any man of many. Measured by the Babur-nama standard, the diction of the Memoirs is redundant throughout, and frequently over-coloured. Of this a pertinent example is provided by a statement of which a minimum of seven occurrences forms my example, namely, that such or such a man whose life Babur sketches was vicious or a vicious person (fisq, fāsiq). Erskine once renders the word by “vicious” but elsewhere enlarges to “debauched, excess of sensual enjoyment, lascivious, libidinous, profligate, voluptuous”. The instances are scattered and certainly Erskine could not feel their collective effect, but even scattered, each does its ill-part in distorting the Memoirs portraiture of the man of the one word.28

Postscript of Thanks

I take with gratitude the long-delayed opportunity of finishing my book to express the obligation I feel to the Council of the Royal Asiatic Society for allowing me to record in the Journal my Notes on the Turki Codices of the Babur-nama begun in 1900 and occasionally appearing till 1921. In minor convenience of work, to be able to gather those progressive notes together and review them, has been of value to me in noticeable matters, two of which are the finding and multiplying of the Haidarabad Codex, and the definite clearance of the confusion which had made the Bukhara (reputed) Babur-nama be mistaken for a reproduction of Babur’s true text.

Immeasurable indeed is the obligation laid on me by the happy community of interests which brought under our roof the translation of the biographies of Babur, Humayun, and Akbar. What this has meant to my own work may be surmised by those who know my husband’s wide reading in many tongues of East and West, his retentive memory and his generous communism in knowledge. One signal cause for gratitude to him from those caring for Baburiana, is that it was he made known the presence of the Haidarabad Codex in its home library (1899) and thus led to its preservation in facsimile.

It would be impracticable to enumerate all whose help I keep in grateful memory and realize as the fruit of the genial camaraderie of letters.

Annette S. Beveridge.Pitfold, Shottermill, Haslemere.

August, 1921.

SECTION I. FARGHĀNA

AH. – Oct. 12th 1493 to Oct. 2nd 1494 AD

In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate.

In29 the month of Ramẓān of the year 899 (June 1494) and in the twelfth year of my age,30 I became ruler31 in the country of Farghāna.

(a. Description of Farghāna.)

Farghāna is situated in the fifth climate32 and at the limit of settled habitation. On the east it has Kāshghar; on the west, Samarkand; on the south, the mountains of the Badakhshān border; on the north, though in former times there must have been towns such as Ālmālīgh, Ālmātū and Yāngī which in books they write Tarāz,33 at the present time all is desolate, no settled population whatever remaining, because of the Mughūls and the Aūzbegs.34

Farghāna is a small country,35 abounding in grain and fruits. It is girt round by mountains except on the west, i. e. towards Khujand and Samarkand, and in winter36 an enemy can enter only on that side.

The Saiḥūn River (daryā) commonly known as the Water of Khujand, comes into the country from the north-east, flows westward through it and after passing along the north of Khujand and the south of Fanākat,37 now known as Shāhrukhiya, turns directly north and goes to Turkistān. It does not join any sea38 but sinks into the sands, a considerable distance below [the town of] Turkistān.

Farghāna has seven separate townships,39 five on the south and two on the north of the Saiḥūn.

Of those on the south, one is Andijān. It has a central position and is the capital of the Farghāna country. It produces much grain, fruits in abundance, excellent grapes and melons. In the melon season, it is not customary to sell them out at the beds.40 Better than the Andijān nāshpātī,41 there is none. After Samarkand and Kesh, the fort42 of Andijān is the largest in Mawārā’u’n-nahr (Transoxiana). It has three gates. Its citadel (ark) is on its south side. Into it water goes by nine channels; out of it, it is strange that none comes at even a single place.43 Round the outer edge of the ditch44 runs a gravelled highway; the width of this highway divides the fort from the suburbs surrounding it.

Andijān has good hunting and fowling; its pheasants grow so surprisingly fat that rumour has it four people could not finish one they were eating with its stew.45

Andijānīs are all Turks, not a man in town or bāzār but knows Turkī. The speech of the people is correct for the pen; hence the writings of Mīr ‘Alī-shīr Nawā’ī,46 though he was bred and grew up in Hīrī (Harāt), are one with their dialect. Good looks are common amongst them. The famous musician, Khwāja Yūsuf, was an Andijānī.47 The climate is malarious; in autumn people generally get fever.48

Again, there is Aūsh (Ūsh), to the south-east, inclining to east, of Andijān and distant from it four yīghāch by road.49 It has a fine climate, an abundance of running waters50 and a most beautiful spring season. Many traditions have their rise in its excellencies.51 To the south-east of the walled town (qūrghān) lies a symmetrical mountain, known as the Barā Koh;52 on the top of this, Sl. Maḥmūd Khān built a retreat (ḥajra) and lower down, on its shoulder, I, in 902AH. (1496AD.) built another, having a porch. Though his lies the higher, mine is the better placed, the whole of the town and the suburbs being at its foot.

The Andijān torrent53 goes to Andijān after having traversed the suburbs of Aūsh. Orchards (bāghāt)54 lie along both its banks; all the Aūsh gardens (bāghlār) overlook it; their violets are very fine; they have running waters and in spring are most beautiful with the blossoming of many tulips and roses.

On the skirt of the Barā-koh is a mosque called the Jauza Masjid (Twin Mosque).55 Between this mosque and the town, a great main canal flows from the direction of the hill. Below the outer court of the mosque lies a shady and delightful clover-meadow where every passing traveller takes a rest. It is the joke of the ragamuffins of Aūsh to let out water from the canal56 on anyone happening to fall asleep in the meadow. A very beautiful stone, waved red and white57 was found in the Barā Koh in ‘Umar Shaikh Mīrzā’s latter days; of it are made knife handles, and clasps for belts and many other things. For climate and for pleasantness, no township in all Farghāna equals Aūsh.

Again there is Marghīnān; seven yīghāch58 by road to the west of Andijān, – a fine township full of good things. Its apricots (aūrūk) and pomegranates are most excellent. One sort of pomegranate, they call the Great Seed (Dāna-i-kalān); its sweetness has a little of the pleasant flavour of the small apricot (zard-alū) and it may be thought better than the Semnān pomegranate. Another kind of apricot (aūrūk) they dry after stoning it and putting back the kernel;59 they then call it subḥānī; it is very palatable. The hunting and fowling of Marghīnān are good; āq kīyīk60 are had close by. Its people are Sārts,61 boxers, noisy and turbulent. Most of the noted bullies (jangralār) of Samarkand and Bukhārā are Marghīnānīs. The author of the Hidāyat62 was from Rashdān, one of the villages of Marghīnān.

Again there is Asfara, in the hill-country and nine yīghāch63 by road south-west of Marghīnān. It has running waters, beautiful little gardens (bāghcha) and many fruit-trees but almonds for the most part in its orchards. Its people are all Persian-speaking64 Sārts. In the hills some two miles (bīrshar‘ī) to the south of the town, is a piece of rock, known as the Mirror Stone.65 It is some 10 arm-lengths (qārī) long, as high as a man in parts, up to his waist in others. Everything is reflected by it as by a mirror. The Asfara district (wilāyat) is in four subdivisions (balūk) in the hill-country, one Asfara, one Warūkh, one Sūkh and one Hushyār. When Muḥammad Shaibānī Khān defeated Sl. Maḥmūd Khān and Alacha Khān and took Tāshkīnt and Shāhrukhiya,66 I went into the Sūkh and Hushyār hill-country and from there, after about a year spent in great misery, I set out (‘azīmat) for Kābul.67

Again there is Khujand,68 twenty-five yīghāch by road to the west of Andijān and twenty-five yīghāch east of Samarkand.69 Khujand is one of the ancient towns; of it were Shaikh Maṣlaḥat and Khwāja Kamāl.70 Fruit grows well there; its pomegranates are renowned for their excellence; people talk of a Khujand pomegranate as they do of a Samarkand apple; just now however, Marghīnān pomegranates are much met with.71 The walled town (qūrghān) of Khujand stands on high ground; the Saiḥūn River flows past it on the north at the distance, may be, of an arrow’s flight.72 To the north of both the town and the river lies a mountain range called Munūghul;73 people say there are turquoise and other mines in it and there are many snakes. The hunting and fowling-grounds of Khujand are first-rate; āq kīyīk,74 būghū-marāl,75 pheasant and hare are all had in great plenty. The climate is very malarious; in autumn there is much fever;76 people rumour it about that the very sparrows get fever and say that the cause of the malaria is the mountain range on the north (i. e. Munūghul).

Kand-i-badām (Village of the Almond) is a dependency of Khujand; though it is not a township (qaṣba) it is rather a good approach to one (qaṣbacha). Its almonds are excellent, hence its name; they all go to Hormuz or to Hindūstān. It is five or six yīghāch77 east of Khujand.

Between Kand-i-badām and Khujand lies the waste known as Hā Darwesh. In this there is always (hamesha) wind; from it wind goes always (hameshā) to Marghīnān on its east; from it wind comes continually (dā’im) to Khujand on its west.78 It has violent, whirling winds. People say that some darweshes, encountering a whirlwind in this desert,79 lost one another and kept crying, “Hāy Darwesh! Hāy Darwesh!” till all had perished, and that the waste has been called Hā Darwesh ever since.

Of the townships on the north of the Saiḥūn River one is Akhsī. In books they write it Akhsīkīt80 and for this reason the poet As̤iru-d-dīn is known as Akhsīkītī. After Andijān no township in Farghāna is larger than Akhsī. It is nine yīghāch81 by road to the west of Andijān. ‘Umar Shaikh Mīrzā made it his capital.82 The Saiḥūn River flows below its walled town (qūrghān). This stands above a great ravine (buland jar) and it has deep ravines (‘uṃiq jarlār) in place of a moat. When ‘Umar Shaikh Mīrzā made it his capital, he once or twice cut other ravines from the outer ones. In all Farghāna no fort is so strong as Akhsī. *Its suburbs extend some two miles further than the walled town.* People seem to have made of Akhsī the saying (mis̤al), “Where is the village? Where are the trees?” (Dih kujā? Dirakhtān kujā?) Its melons are excellent; they call one kind Mīr Tīmūrī; whether in the world there is another to equal it is not known. The melons of Bukhārā are famous; when I took Samarkand, I had some brought from there and some from Akhsī; they were cut up at an entertainment and nothing from Bukhārā compared with those from Akhsī. The fowling and hunting of Akhsī are very good indeed; āq kīyīk abound in the waste on the Akhsī side of the Saihūn; in the jungle on the Andijān side būghū-marāl,83 pheasant and hare are had, all in very good condition.

Again there is Kāsān, rather a small township to the north of Akhsī. From Kāsān the Akhsī water comes in the same way as the Andijān water comes from Aūsh. Kāsān has excellent air and beautiful little gardens (bāghcha). As these gardens all lie along the bed of the torrent (sā’ī) people call them the “fine front of the coat.”84 Between Kāsānīs and Aūshīs there is rivalry about the beauty and climate of their townships.