Полная версия

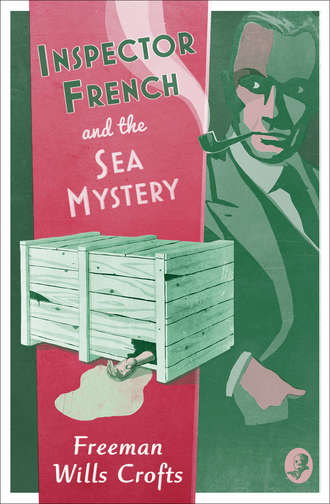

Inspector French and the Sea Mystery

However, the work had to be done, and presently the body was lying on a table which had been placed for the purpose in an outhouse. It was dressed in underclothes only—shirt, vest, drawers, and socks. The suit, collar, tie, and shoes had been removed. An examination showed that none of the garments bore initials.

Nor were there any helpful marks on the crate. There were tacks where a label had been attached, but the label had been torn off. A round steel bar of three or four stones weight had also been put in, evidently to ensure the crate sinking.

The most careful examination revealed no clue to the man’s identity. Who he was and why he had been murdered were as insoluble problems as how the crate came to be where it was found.

For over an hour the little party discussed the matter, and then the chief constable came to a decision.

‘I don’t believe it’s a local case,’ he announced. ‘That crate must in some way have come from a ship: I don’t see how it could have been got there from the shore. And if it’s not a local case I think we’ll consider it not our business. We’ll call in Scotland Yard. Let them have the trouble of it. I’ll ring up the Home Office now and we’ll have a man here this evening. Tomorrow will be time enough for the inquest and the C.I.D. man will be here and can ask what questions he likes.’

Thus it came to pass that Inspector Joseph French on that same afternoon travelled westwards by the 1.55 p.m. luncheon car express from Paddington.

2

Inspector French Gets Busy

Dusk was already falling when a short, rather stout man with keen blue eyes from which a twinkle never seemed far removed, alighted from the London train at Burry Port and made his way to Sergeant Nield, who was standing near the exit, scrutinising the departing travellers.

‘My name is French,’ the stranger announced: ‘Inspector French of the C.I.D. I think you are expecting me?’

‘That’s right, sir. We had a ’phone from headquarters that you were coming on this train. We’ve been having trouble, as you’ve heard.’

‘I don’t often take a trip like this without finding trouble at the end of it. We’re like yourself, sergeant; we have to go out to look for it. But we don’t often have to look for it in such fine country as this. I’ve enjoyed my journey.’

‘The country’s right enough if you’re fond of coal,’ Nield rejoined with some bitterness. ‘But now, Mr French, what would you like to do? I expect you’d rather get fixed up at an hotel and have some dinner before anything else? I think the Bush Arms is the most comfortable.’

‘I had tea a little while ago. If it’s the same to you, sergeant, I’d rather see what I can before the light goes. I’ll give my bag to the porter, and he can fix me up a room. Then I hope you’ll come back and dine with me and we can have a talk over our common trouble.’

The sergeant accepted with alacrity. He had felt somewhat aggrieved at the calling in of a stranger from London, believing it to be a reflection on his own ability to handle the case. But this cheery, good-humoured-looking man was very different from the type of person he was expecting. This inspector did not at all appear to have come down to put the local men in their places and show them what fools they were. Rather he seemed to consider Nield an honoured colleague in a difficult job.

But though the sergeant did not know it, this was French’s way. He was an enthusiastic believer in the theory that with ninety-nine persons out of a hundred you can lead better than you can drive. He therefore made it an essential of his method to be pleasant and friendly to those with whom he came in contact, and many a time he had found that it had brought the very hint that he required from persons who at first had given him only glum looks and tight lips.

‘I should like to see the body and the crate, and if possible have a walk round the place,’ French went on. ‘Then I shall understand more clearly what you have to tell me. Is the inquest over?’

‘No, it is fixed for eleven o’clock tomorrow. The chief constable thought you would like to be present.’

‘Very kind of him: I should. I gathered that the man had been dead for some time?’

‘Between five and six weeks, the doctors said. Two doctors saw the body, our local man, Dr Crowth, and a friend of the chief constable’s, Dr Wilbraham. They were agreed about the time.’

‘Did they say the cause of death?’

‘No, they didn’t, but there can’t be much doubt about that. The whole face and head is battered in. It’s not a nice sight, I can tell you.’

‘I don’t expect so. Your report said that the crate was found by a fisherman?’

‘An amateur fisherman, yes,’ and Nield repeated Mr Morgan’s story.

‘That’s just the lucky way things happen, isn’t it!’ French exclaimed. ‘A man commits a crime and he takes all kinds of precautions to hide it, and then some utterly unexpected coincidence happens—who could have foreseen a fisherman hooking the crate—and he is down and out. Lucky for us and for society too. But I’ve seen it again and again. I’ve seen things happen that a writer couldn’t put into a book, because nobody would believe them possible, and I’m sure so have you. There’s nothing in this world stranger than the truth.’

The sergeant agreed, but without enthusiasm. In his experience it was the ordinary and obvious thing that happened. He didn’t believe in coincidences. After all it wasn’t such a coincidence that a fisherman who lowered a line on the site of the crate should catch his hooks in it. The crate was in the area over which this man fished. There was nothing wonderful about it.

But a further discussion of the point was prevented by their arrival at the police station. They passed to the outhouse containing the body, and French forthwith began his examination.

The remains were those of a man slightly over medium height, of fairly strong build, and who had seemingly been in good health before death. The face had been terribly mishandled. It was battered in until the features were entirely obliterated. The ears even were torn and bruised and shapeless. The skull was evidently broken at the forehead, so, as the sergeant had said, there was here an injury amply sufficient to account for death. It was evident also that a post-mortem had been made. Altogether French had seldom seen so horrible a spectacle.

But his professional instincts were gratified by a discovery which he hoped might assist in the identification of the remains. On the back of the left arm near the shoulder was a small birthmark of a distinctive triangular shape. Of this he made a dimensioned sketch, having first carefully examined it and assured himself it was genuine.

But beyond these general observations he did not spend much time over the body. Having noted that the fingers were too much decomposed to enable prints to be taken, he turned his attention to the clothes, believing that all the further available information as to the remains would be contained in the medical report.

Minutely he examined the underclothes, noting their size and quality and pattern, searching for laundry marks or initials, or for mendings or darns. But except that the toe of the left sock had been darned with wool of too light a shade, there was nothing to distinguish the garments from others of the same kind. Though he did not expect to get help from the clothes, French in his systematic way entered a detailed description of them in his note-book. Then he turned to the crate.

It measured two feet three inches by two feet four, and was three feet long. Made of spruce an inch thick, it was strongly put together and clamped with iron corner pieces. The boards were tongued and grooved, and French thought that under ordinary conditions it should be water-tight. He examined its whole surface, but here again he had no luck. Though there were a few bloodstains inside, no label or brand or identifying mark showed anywhere. Moreover, there was nothing in its shape or size to call for comment. The murderer might have obtained it from a hundred sources, and French did not see any way in which it could be traced.

That it had been labelled at one time was evident. The heads of eight tacks formed a parallelogram which clearly represented the position of a card. It also appeared to have borne attachments of some heavier type, as there were seven nail-holes of about an eighth of an inch in diameter at each of two opposite corners. Whatever these fittings were they had been removed and the nails withdrawn.

‘How long would you say this had been in the water?’ French asked, running his fingers over the sodden wood.

‘I asked Manners, our coastguard, that question,’ the sergeant answered. ‘He said not very long. You see, there are no shells nor seaweed attaching to it. He thought about the time the doctors mentioned, say between five and six weeks.’

The bar was a bit of old two-inch shafting, some fourteen inches long, and was much rusted from its immersion. It had evidently been put in as a weight to ensure the sinking of the crate. Unfortunately it offered no better clue to the sender than the crate itself.

French added these points to his notes and again addressed the sergeant.

‘Have you a good photographer in the town?’

‘Why, yes, pretty good.’

‘Then I wish you’d send for him. I want some photographs of the body, and they had better be done first thing in the morning.’

When the photographer had arrived and had received his instructions French went on: ‘That, sergeant, seems to be all we can do now. It’s too dark to walk round tonight. Suppose we get along to the hotel and see about that dinner?’

During a leisurely meal in the private room French had engaged they conversed on general topics, but later, over a couple of cigars, they resumed their discussion of the tragedy. The sergeant repeated in detail all that he knew of the matter, but he was able neither to suggest clues upon which to work, nor yet to form a theory as to what had really happened.

‘It’s only just nine o’clock,’ French said, when the subject showed signs of exhaustion. ‘I think I’ll go round and have a word with this Mr Morgan, and then perhaps we could see the doctor—Crowth, you said his name was? Will you come along?’

Mr Morgan, evidently thrilled by his visitor’s identity, repeated his story still another time. French had brought from London a large scale Ordnance map of the district, and on it he got Mr Morgan to mark the bearings he had taken, and so located the place the crate had lain. This was all the fresh information French could obtain, and soon he and Nield wished the manager goodnight and went on to the doctor’s.

Dr Crowth was a bluff, middle-aged man with a hearty manner and a kindly expression. He was off-hand in his greeting, and plunged at once into his subject.

‘Yes,’ he said in answer to French’s question, ‘we held a post-mortem, Dr Wilbraham and I, and we found the cause of death. Those injuries to the face and forehead were all inflicted after death. They were sufficient to cause death, but they did not do so. The cause of death was a heavy blow on the back of the head with some soft, yielding instrument. The skull was fractured, but the skin, though contused, was unbroken. Something like a sandbag was probably used. The man was struck first and killed, and then his features were destroyed, with some heavy implement such as a hammer.’

‘That’s suggestive, isn’t it?’ French commented.

‘You mean that the features were obliterated after death to conceal the man’s identity?’

‘No, I didn’t mean that, though of course it is true. What I meant was that the man was murdered in some place where blood would have been noticed, had it fallen. He was killed, not with a sharp-edged instrument, though one was available, but with a blunt one, lest bleeding should have ensued. Then when death had occurred the sharp-edged instrument was used and the face disfigured. I am right about the bleeding, am I not?’

‘Oh, yes. A dead body does not bleed, or at least not much. But I do not say that you could inflict all those injuries without leaving some bloodstains.’

‘No doubt, but still I think my deduction holds. There were traces of blood in the crate, but only slight. What age was the man, do you think, doctor?’

‘Impossible to say exactly, but probably middle-aged: thirty-five to fifty-five.’

‘Any physical peculiarities?’

‘I had better show you my report. It will give you all I know. In fact, you can keep this copy.’

French ran his eyes over the document, noting the points which might be valuable. The body was that of a middle-aged man five feet ten inches high, fairly broad and well built, and weighing thirteen stone. The injuries to the head and face, were such that recognition from the features would be impossible. There was only one physical peculiarity which might assist identification, a small triangular birthmark on the back of the left arm.

The report then gave technical details of the injuries and the condition the body was in when found, with the conclusion that death had probably occurred some thirty-five to forty days earlier. French smiled ruefully when he had finished reading.

‘There’s not overmuch to go on, is there?’ he remarked. ‘I suppose nothing further is likely to come out at the inquest?’

‘Unless someone that we don’t know of comes forward with information, nothing,’ the sergeant answered. ‘We have made all the inquiries, that we could think of.’

‘As far as I am concerned,’ Dr Crowth declared, ‘I don’t see that you have anything to go on at all. I shouldn’t care for your job, Inspector. How on earth will you start trying to clear up this puzzle? To me it seems absolutely insoluble.’

‘Cases do seem so at first,’ French returned, ‘but it’s wonderful how light gradually comes. It is almost impossible to commit a murder without leaving a clue, and if you think it over long enough you usually get it. But this, I admit, is a pretty tough proposition.’

‘Have you ever heard of anything like it before?’

‘So far it rather reminds me of a case investigated several years ago by my old friend Inspector Burnley—he’s retired now. A cask was sent from France to London which was found to contain the body of a young married Frenchwoman, and it turned out that her unfaithful husband had murdered her. He had in his study at the time a cask in which a group of statuary which he had just purchased had arrived, and he disposed of the body by packing it in the cask and sending it to England. It might well be that the same thing had happened in this case: that the murderer had purchased something which had arrived in this crate and that he had used the latter to get rid of the body. And, as you can see, doctor, that at once suggests a line of inquiry. What firm uses crates of this kind to despatch their goods and to whom were such crates sent recently? This is the sort of inquiry which gets us our results.’

‘That is very interesting. All the same, I’m glad it’s your job and not mine. I remember reading of that case you mention. The papers were absolutely full of it at the time. I thought it an extraordinary affair, almost like a novel.’

‘No doubt, but there is this difference between a novel and real life. In a novel the episodes are selected and the reader is told those which are interesting and which get results. In real life we try perhaps ten or twenty lines which lead nowhere before we strike the lucky one. And in each line we make perhaps hundreds of inquiries, whereas the novel describes one. It’s like any other job, you get results by pegging away. But it is interesting on the whole, and it has its compensations. Well, doctor, I mustn’t keep you talking all night. I shall see you at the inquest tomorrow.’

French’s gloomy prognostications were justified next day when the proceedings in the little courthouse came to an end. Nothing that was not already known came out, and the coroner adjourned the inquiry for three weeks to enable the police to conclude their investigations.

What those investigations were to consist of was the problem which confronted French when after lunch he sat down in the deserted smoking-room of the little hotel to think matters out.

In the first place there was the body. What lines of inquiry did the body suggest?

One obviously. Some five or six weeks previously a fairly tall, well-built man of middle-age had disappeared. He might merely have vanished without explanation, or more probably, circumstances had been arranged to account for his absence. In the first case information should be easily obtainable. But the second alternative was a different proposition. If the disappearance had been cleverly screened it might prove exceedingly difficult to locate. At all events, inquiries on the matter must represent the first step.

It was clearly impossible to trace any of the clothes, with the possible exception of the sock. But even from the sock French did not think he would learn anything. It was of a standard pattern, and the darning of socks with wool of not quite the right shade was too common to be remembered. At the same time he noted it as a possible line of research.

Next he turned his attention to the crate, and at once two points struck him.

Could he trace the firm who had made the crate? Of this he was doubtful: it was not sufficiently distinctive. There must be thousands of similar packing cases in existence, and to check up all of them would be out of the question. Besides, it might not have been supplied by a firm. The murderer might have had it specially made, or even have made it himself. Here again, however, French could but try.

The second point was: How had the crate got to the bottom of the Burry Inlet? This was a question that he must solve, and he turned all his energies towards it.

There were here two possibilities. Either the crate had been thrown into the water and had sunk at the place where it was found, or it had gone in elsewhere and been driven forward by the action of the sea. He considered these ideas in turn.

To have sunk at the place it was thrown in postulated a ship or boat passing over the site. From the map, steamers approaching or leaving Llanelly must go close to the place, and might cross it. But French saw that there were grave difficulties in the theory that the crate had been dropped overboard from a steamer. It was evident that the whole object of the crate was to dispose of the body secretly. The crate, however, could not have been secretly thrown from a steamer. Whether it were let go by hand or by a winch, several men would know about it. Indeed news of so unusual an operation would almost certainly spread to the whole crew, and if the crate were afterwards found, someone of the hands would be sure to give the thing away. Further, if the crate were being got rid of from a steamer it would have been done far out in deep water and not at the entrance to a port.

For these reasons French thought that the ship might be ruled out, and he turned his attention to the idea of a row-boat.

But here a similar objection presented itself. The crate was too big and heavy to be dropped from a small boat. French tried to visualise the operation. The crate could only be placed across the stern: in any other position it would capsize the boat. Then it would have to be pushed off. This could not be done by one man: he doubted whether it could be done by two. But even if it could, these two added to the weight of the crate would certainly cause disaster. He did not believe the operation possible without a large boat and at least three men, and he felt sure the secret would not have been entrusted to so many.

It seemed to him then that the crate could not have been thrown in where it was found. How else could it have got there?

He thought of Mr Morgan’s suggestion of a wreck from which it might have been washed up into the Inlet, but according to the sergeant, there had been no wreck. Besides, the crate was undamaged outside, and it was impossible that it could have been torn out through the broken side of a ship or washed overboard without leaving some traces.

French lit a fresh pipe and began to pace the deserted smoking room. He was exasperated because he saw that his reasoning must be faulty. All that he had done was to prove that the crate could not have reached the place where it was found.

For some minutes he couldn’t see the snag, then it occurred to him that he had been assuming too much. He had taken it for granted that the crate had sunk immediately on falling into the water. The weights of the crate itself, the body, and the bar of steel had made him think so. But was he correct? Would the air the crate contained not give it buoyancy for a time, until at least some water had leaked in?

If so, the fact would have a considerable bearing on his problem. If the crate had been floated to the place he was halfway to a solution.

Suddenly the possible significance of the fourteen holes occurred to him. He had supposed they were nail-holes, but now he began to think differently. Suppose they were placed there to admit the water—slowly, so that the crate should float for a time and then sink? Their position was suggestive; they were at diagonally opposite corners of the crate. That meant that at least one set must be under water, no matter in what position the crate was floating. It also meant that the other set provided a vent for the escape of the displaced air.

The more French thought over the idea, the more probable it seemed. The crate had been thrown into the sea, most likely from the shore and when the tide was ebbing, and it had floated out into the Inlet. By the time it had reached the position in which it was found, enough water had leaked in to sink it.

He wondered if any confirmatory evidence of the theory were available. Then an idea struck him, and walking to the police station, he asked for Sergeant Nield.

‘I want you, sergeant, to give me a bit of help,’ he began. ‘First, I want the weights of the crate and the bar of iron. Can you get them for me?’

‘Certainly. We’ve nothing here that would weigh them, but I’ll send them to the railway station. You’ll have the weights in half an hour.’

‘Good man! Now there is one other thing. Can you borrow a Molesworth for me?’

‘A Molesworth?’

‘A Molesworth’s Pocket Book of Engineering Formulæ. You’ll get it from any engineer or architect.’

‘Yes, I think I can manage that. Anything else?’

‘No, sergeant, that’s all, except that before you send away the crate I want to measure those nail holes.’

French took a pencil from his pocket and sharpened it to a long thin evenly rounded point. This he pushed into the nail holes, marking how far it went in. Then with a pocket rule he measured the diameter of the pencil, the length of the sharpened portion, and the distance the latter had entered. From these dimensions a simple calculation told him that the holes were all slightly under one-sixth of an inch in diameter.

The sergeant was an energetic man, and before the half hour was up he had produced the required weights and the engineer’s pocket book. French, returning to the hotel, sat down with the Molesworth and a few sheets of paper, and began with some misgivings to bury himself in engineering calculations.

First he added the weights of the crate, the body and the steel bar: they came to 29 stone or 406 lbs. Then he found that the volume of the crate was just a trifle over 15 cubic feet. This latter multiplied by the weight of a cubic foot of sea-water—64 lbs.—gave a total of 985 lbs. as the weight of water the crate would displace if completely submerged. But if the weight of the crate was 406 lbs., and the weight of the water it displaced was 985 lbs., it followed that not only would it float, but it would float with a very considerable buoyancy, represented by the difference between these two, or 579 lbs. The first part of his theory was therefore tenable.

But the moment the crate was thrown into the sea, water would begin to run in through the lower holes. French wondered if he could calculate how long it would take to sink.