Полная версия

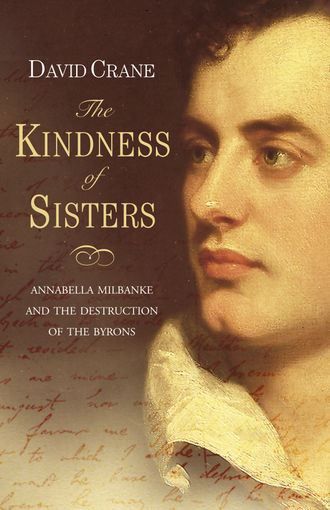

The Kindness of Sisters: Annabella Milbanke and the Destruction of the Byrons

Crippled with a deformity of his right foot, abandoned by his rake of a father, brought up in poverty by his violently possessive mother, alternately abused and terrified by his Calvinist nurse, Byron might have had little choice in the matter, but no psychological pleading can disguise the gusto with which he embraced his fate. In recent years it has become the fashion among biographers to present him as some kind of ‘monster-victim’ of this childhood, but the exhilarating truth about Byron is that he was an outsider by intelligence and will, an enemy by instinct, sensibility, temperament and politics of all that this ‘tight little island’* stands for.

No major English poet – except perhaps his hero, Alexander Pope – has made such creative capital out of a sense of alienation and grievance. It would take most of his life before the combination of exile and technical mastery matured these feelings into the great verse of Don Juan, but from his first callow satire the poet fed ruthlessly off his sense of difference, transmuting all the social and physical insecurities of childhood into the antinomian hauteur of the Byronic hero.

And the key word there is ‘Byronic’, because it was the glee with which Byron seized on the idea of hereditary doom that has made his name synonymous with the rebel outsider. The more unstable elements of his character probably owed as much to his mother’s Gordon blood as the paternal line, but it was exclusively through the history of crime and excess that was ‘Mad Jack’ Byron’s bequest to his son that a perverted Calvinism and the curse of deformity coalesced into a single, liberating myth of predestined damnation and revolt.

From the moment when, as a nine year old child, after the successive deaths of father, cousin, uncle and the ‘Wicked Lord’, he came into the title and first saw the ruins of his ancestral home near Nottingham, the shape of this rebellion was set. Newstead had originally been founded as an Augustinian priory in the reign of Henry II, and for all the changes it was still the great west front of the former church that gave the house its special character, a soaring, pinnacled and traceried façade behind which nothing stood, a piece of history preserved as theatre as wonderfully and spuriously evocative as everything else about the child’s bankrupt inheritance.

If it is impossible to imagine any nine-year old would be impervious to the romance of Newstead, no one but a Byron could have gloried so in its evidence of ancestral ruin. The priory had first come into the family in 1537 at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, but the ruthless transforming energies of Henrician England had long disappeared there, leaving house and lands mouldering in the same irreversible decay, the Byron name stained by murder, its deer slaughtered, woods felled, mining rights leased, rooms bare, its ruined east wing open to the skies.

Among the great English Romantics, Byron is unique in an almost complete absence of feel for his native landscape, and the cloistered world of Newstead quite literally set in stone a sense of physical alienation that had begun in his infancy. In his earliest verse there was a certain amount of Ossian-like posturing over the mountains of his childhood, but it was significantly the ruined priory that became what Pope’s Twickenham grotto and garden had been to another crippled outsider – the emotional and physical context of his creative life, the ‘other place’ of the imagination where he could reinvent himself in the successive alter-egos with which he would take on the world. ‘Newstead, fast falling, once resplendent dome’, Byron saluted it in one of his juvenile poems,

Religion’s shrine! Repentant HENRY’S pride!

Of warriors, monks, and dames the cloister’d tomb,

Whose pensive shades around thy ruins glide,

Hail to the pile! More honour’d in the fall

Than modern mansions in their pillar’d state;

Proudly majestic frowns thy vaulted hall,

Scowling defiance on the blasts of fate17

In his adult life Newstead would be more a financial burden than a retreat, but its blend of history and loss retained a central place in his imagination. As a boy at Harrow and then Cambridge his sense of identity was wrapped up with the Byronic inheritance it embodied, but even after he had been compelled to sell it, the lessons of pride and vulnerability he had learned under its roof always remained with him,

It influenced everything in his life, his strengths and weaknesses, his politics and social manner – the awkward mix of arrogance and uncertainty – and above all the poetry that can often seem an emanation of childhood alienation. In the last great poem of his life he returned to Newstead with a freshness that underlines its importance to him, but if it is impossible to imagine the satirist of Don Juan without acknowledging the role Newstead played in his development it is as hard not to see its influnece in the lack of ‘place’ that is such a glaring weakness of his descriptive verse.

Nothing is ever as simple as that with Byron, of course, but his deliberate, ‘aristocratic’ obtuseness about the business of poetry that clouds the issue here was ultimately no more than a manifestation of the same insecurity. One only has to think of the ease with which Keats can move through an English landscape in darkness and identify every scent and sound to see what is missing from Byron’s verse, but in some adolescent way it would have seemed beneath him to look with that kind of particularity. ‘“Where is the green your friend the Laker talks such fustian about”, Trelawny recalled in an anecdote which – true or not – neatly brings Byron’s hostility to a world with which he was at odds and poetic sensibility into a single focus,

“Who ever”, asked Byron, “saw a green sky?”

Shelley was silent, knowing that if he replied, Byron would give vent to his spleen. So I said, “The sky in England is oftener green than blue.”

“Black, you mean,” rejoined Byron; and this discussion brought us to his door.18

This insensitivity to his surroundings might seem an odd criticism of a poet whose evocation of the Greek landscape inspired a generation to fight and die for its freedom, but even then it was an idea of landscape rather than landscape itself that quickened his creativity, a sense of decline and loss that was as much imaginative projection as classical association.

It is no coincidence, either, that the one place that could genuinely vie with Greece in Byron’s mind was Venice, and again it was the palpable air of decay that clung to the Serenissima in her dotage that gripped his imagination. There are times in fact when this almost reflex melancholy can strike an oddly adolescent note in a writer of his wit and sophistication, and yet it is precisely this quality of arrested growth that links boy and man, and – critically – man and poet in a sense of alienation that found its first and deepest expression in Newstead.

The greatness of D.H. Lawrence’s novels, as F.R. Leavis remarked, was the proof they give that he lived, and the same could be said with even more validity of Byron’s poetry. In the wonderful satires of his last years he produced some of the finest comic poetry in the English language, and yet for all its brilliance and fun the ultimate fascination of his verse lies in the testament it offers to the courage and defiance with which Byron lived his life.

It was a defiance that darkened everything, from the wounded bitterness with which he responded to rejection, to the reckless and self-destructive exhibitionism with which he greeted success. There are other outsiders for whom success comes as a kind of belated membership card, but it was perhaps the defining hallmark of Byronic rebellion that triumph only propelled him from the defence onto the attack, driving him in an ascending trajectory from Newstead on an inevitable collision course with the community he despised.

This is not another biography of Byron – nor even of the notorious marriage that led to his final rupture with England – but an exploration of this timeless battle between the values he stood for and those of the community. There are any number of English authors around whose lives a similar argument might be built, but the unity of his life and art and the fame which surrounded Byron make him the one writer whose history defines in some permanent way what it means to be English.

At the height of the marriage crisis, it was claimed with a breathtaking simplicity that men and women’s attitudes to him demonstrated whether they were ‘good’ or ‘bad’, and nearly fifty years after his death Harriet Beecher Stowe berated the English nation for any softening in its attitude to him. It seemed to the American novelist that the moral sinews of the nation had been radically weakened by his verse and life, and while she was in some ways a case apart, there was too much agreement on all sides of the political spectrum to dismiss hers as the naïve voice of New England puritanism.

‘England, England!’19 she lamented, and if she was wrong in her diagnosis, she was right that the threat Byron offered had not died with him. For the dozen years which followed the triumph of Childe Harold, his poetry and personality had sent his contemporaries scuttling for cover behind the city walls, and yet it was only in death that his rebellion was revealed in its full destructiveness, consuming and maiming lives with all the inexorable power of Greek tragedy until it reached its final, savage climax in the ‘High Noon’ of Byronic Romanticism that forms the core of this book.

This was the first and last confrontation in twenty years between the two women who had been brought together by his marriage and fought over his corpse, the sister he had loved and the wife who had brought about his exile. It took place at the White Hart at Reigate, a small town some twenty miles south of London, on 8 April 1851, the year of the Great Exhibition, the year Victorian England gloried in its prosperity and moral superiority with a complacency Byron would have loathed.

Byron, though, had been dead for almost twenty-seven years. Of his great contemporaries, Shelley had been gone for twenty-nine, Keats thirty, Coleridge seventeen, even Wordsworth – the ‘Wordswords’ of Don Juan as he had long since become – one.

And thirteen years into Victoria’s reign, it was a different world. Tennyson, who as a schoolboy had carved Byron’s name into a rock on hearing the news from Missolonghi, had just been presented to the Queen as the new Poet Laureate, his tortured frame tightly trussed in the same court dress that Samuel Rogers had once lent his predecessor. Matthew Arnold – that other representative voice of the mid-century – had just become engaged. Trollope was wondering if he would ever make a novelist. Dickens, never one to be seduced by national prosperity, was beginning Bleak House, Mayhew publishing his London Poor. George Eliot was editing at the Westminster Review, Charlotte Bronte squabbling with Thackeray, her sisters Emily and Anne, already dead. Byron’s half-sister, Augusta Leigh, was sixty seven; his widow, Annabella Byron, fifty-eight.

Byron had been dead for almost as long as he had lived, but for the two women who met at the White Hart his memory had all the sharpness of recent bereavement. For the best part of forty years his presence or legacy had alternately enriched and shattered their lives, and this Reigate meeting was the final testament to his dominance, one last dramatic demonstration of the fear and adulation that had convulsed a generation and for which in their polar antagonisms Annabella Byron and Augusta Leigh stand the perfect surrogates.

It is this that gives both the fascination and significance to this meeting, because the battle that climaxed at Reigate is also in miniature the archetypal struggle of the outsider and the community that had raged around Byron ever since the first publication of Childe Harold. The secret histories of these two women have a misery that no repetition can dim, and yet for all the melodrama of the story this book tells, it is the representative quality that gives a kind of Aeschylian grandeur to the history of incest, bastardy, betrayal, love and hate that in Byron’s name and memory bound them together.

If this focus on the Reigate meeting needs no justifying, the form that has been adopted here requires some explanation. In the first and last parts of this book the methods are those of any conventional biography, but if there is a single episode in the whole Byron saga that demands a freer, more speculative approach, it is this last confrontation between Annabella and Augusta at the White Hart.

With that in mind, the form is that of an ‘imaginary dialogue’, and if this is in part because we do not know what was said, it is not necessity that has determined this option. There can be few lives or deaths that have ever been subjected to the same scrutiny as that of Byron’s, and yet as so often with him the most compelling truths of this narrative lie in regions for which the traditional tools of history or biography are simply not enough.

It is not only that scholarship can never deliver the certainties to which it aspires, but that this meeting has less to do with ‘objective truth’ or ascertainable fact than with the kinds of subjective experience that gradually take on an independent and destructive life of their own. Within the restrictions of orthodox biography it would have been possible to chart the chronological path that took Annabella and Augusta from their first meeting to this last, but what biography could never do is dissolve the barriers between past and present or capture the distorting operations of memory, the co-existence of contradictory but equally valid ‘truths’; could never re-open those avenues that, one by one, are closed by life but remain in the mind; could never, most important of all, do full justice to that sense of waste, that consciousness of other possibilities – other ‘selves’, resolutions, aspirations, untapped or thwarted potentialities of human growth – that was Byron’s terrible gift not just to these two women but to his whole generation.

There is, too, another – entirely fortuitous – advantage to a dialogue of this kind, in that the inevitable whiff of Victorian melodrama about it, the sense of characters speaking out of ‘role’, of addressing not each other but the audience beyond, perfectly captures the way in which they spoke. In a letter written just before the meeting at Reigate, Annabella accused Augusta of never saying or writing anything without a third person in mind, and whether or not that is fair to her it certainly is to Annabella herself whose natural mode of address was the statement or deposition made and obsessively recorded with the judgement of posterity in her sights.

And if this reconstructed dialogue is essentially a fiction, it is a fiction that is strictly circumscribed by historical evidence. The old White Hart in Reigate had passed its Regency peak by the time that Annabella chose it and is now long since gone, and the setting here is essentially a theatrical rather than an historical space, its symbolism and props those of a Pre-Raphaelite painting – this after all is the year Ruskin championed the Brotherhood – rather than a Victorian coaching inn doomed by the advent of the train.

There has, too, been a compression of time to contain within the classical unities the final unfolding of these lives, but those are the only liberties taken. There is nothing here, otherwise, that does not have its source in the thousands of letters, statements, depositions, reminiscences and journals that document the relationship of the two women. Much of it, too, is in their own words, spoken, written or reported over a period of more than thirty years. We have the letters that they exchanged before Reigate, and the minutes taken after. We have the notes, written on a slip of paper in a nervous, almost indecipherable hand, that Byron’s widow took with her to the meeting. We have the correspondence that followed. We know their state of health, how they looked, how they dressed, how they sounded, how they stood and walked, their physical responses to pain. Above all, though, in the mere presence of two elderly women – the one frail from chronic ill-health, the other dying – we have the ultimate proof of that obsession with the memory and influence of Byron that makes their story the story of the age itself.

I

A MEETING OF OPPOSITES

On a chill and blustery Tuesday in April 1851, an elderly woman, accompanied by a man in his early thirties, emerged from the entrance at the top of Trafalgar Street in Brighton to take the north-bound railway for Reigate. If anyone in the crowded terminus had noticed either of them it would almost certainly have been the man, a tall and striking figure, whose charismatic preaching at the Holy Trinity had made the names of ‘Brighton’ and ‘Robertson’ synonymous across the English-speaking protestant world.

With her air of genteel invalidism, and discreet, unassuming appearance, it is unlikely that the woman beside him would have attracted a second glance. She had never been more than five foot three in height and in her late fifties seemed scarcely that, a fragile, neat creature with a slight, ‘almost infantine’20 figure, fine delicate hands, deep and striking blue eyes, silver hair, high forehead, and the preternatural pallor of the permanent invalid.

To the circle of her friends, in fact, who watched over her prolonged decline with a complete and willing devotion, it seemed that Annabella Byron hardly belonged to this world at all. There was a calm certainty about her that struck a note of unearthly detachment, an ethereal refinement that seemed to the chosen ‘soulmates’ of these last years to be that of ‘one of the spirits of the just made perfect … hovering on the brink of the eternal world’21.

If anyone had taken a closer look at this pair, however, as they made their way under the soaring gothic of Brighton’s new terminus to the first-class carriages of the London train, there would have been little doubt where the balance of power lay. Thirty five years earlier the young Annabella Byron had appeared to her sister-in-law less as a visiting angel than an avenging spectre, and in the remote and concentrated self-possession of her bearing, it was as if all the frailties or pleasures of life had been purged away to leave behind only a pure, indomitable will.

And yet behind this ‘miracle of mingled weakness and strength’22, as Harriet Beecher Stowe called her, there was a nervousness, an emotional and physical excitability, that raged all the fiercer for its ruthless suppression. In a self-portrait she wrote in the last year of her life she spoke of the ‘burning world within’23 that so few ever saw, and as she took her place beside Robertson, and sat compulsively folding and refolding her scrap of paper with its illegible instructions to herself on it, she knew only too bitterly the cost at which any outward calm had been won.

If she had caught her reflection in the glass before it was swallowed up in the blackness of the Clayton tunnel, she would have been forced to recognise there the evidence of the same grim truth. Forty years earlier, in her second London season, Hayter had painted her with the louche abandon of some Regency Magdalene, but if she had looked now for the face of the young Annabella Milbanke in the reflection that stared back, searching for some trace of all those potentialities and hopes that were frozen when pain and humiliation petrified her strength into the obduracy of a long widowhood, she would have looked in vain.

There would have been something in its unyielding expression, however, in the set of the mouth, in the air of conviction, the concentration, that anyone who had seen her as a child would have had no difficulty recognising. Some years after her death Robertson’s biographer, Frederick Arnold, remarked on the doctrine of ‘personal infallibility’ to which Annabella Byron subscribed in these late years, and if a lifetime of alternating sycophancy and hostility had done their worst to make her what she was, the foundations at least of her old age were laid in the cosseted, self-absorbed childhood of Annabella Milbanke.

To have any real sense of the woman in the train bound for Reigate, or the forces that had shaped her life, it is necessary to go back even further than that, to another generation and world that is best glimpsed in a family portrait by Stubbs that now hangs in the National Gallery in London. On the left of Stubbs’s grouping a young woman of seventeen sits high in the seat of a light carriage, reins and whip competently and prophetically in hand, her face, simultaneously ‘unfinished’ and determined, framed by a white bonnet, her eyes boldly, almost immodestly, engaging with a future that seems in her control.

The girl, Elizabeth Lamb, is pregnant, although it is impossible to tell from the painting. At her side, her father, Sir Ralph Milbanke, his expression serious, leans against the carriage; in the centre, holding the reins of a dappled grey that matches her carriage pony, stands her brother, John; on the right, slightly apart, elegant in profile on a superb bay, is her husband of a year, Peniston Lamb, the future first Lord Melbourne.

There is a sense of calm to the piece, a reserve and unforced serenity that can only come of an unconscious collaboration of artist and sitters. In the distance a rocky outcrop looms over a stretch of water with some vague suggestion of domesticated wildness, but Stubbs’s figures need no background, confidently filling their social and pictorial space, sufficient to themselves under the enveloping protection of a darkly spreading oak.

The oak and the girl, the past and the future, both linked in an unbroken chain to which the figures bear silent, unruffled witness. There is no conversation in this ‘conversation piece’, no interaction almost, just a shared strength that needs no articulating. From the side Peniston Lamb looks across – as well he might – to his formidable young wife, but the gaze is unreturned. Even the horses seem entirely self-contained, blinkered or cropping the grass, indifferent to each other, their owners, or the two dogs that, like a pair of attendant saints, stare up, in that eternal gesture of English portraiture, with unnoticed devotion at their masters.

There is none of the golden glow of other Stubbs paintings here, none of the bucolic ease of his Haymakers, but a cool silvery light warmed only by the pink of Elizabeth’s dress and the answering tinge of the clouds. On a nearby wall an elderly couple also painted by Stubbs aboard their phaeton might be Jane Austen’s Admiral and Mrs Croft, but this group is not about affection or fulfilment but hierarchy and power, about dynastic and cultural certainties, and about what David Piper memorably called that ‘obscure but potent directive of fate’ that gives Stubbs sitters their air of unchallenged and unchallengeable authority.

According to tradition, the Milbanke family traces itself back to a cup-bearer at the court of Mary Queen of Scots, who fled the country after a duel, settling in the north of England. Whatever the maverick promise of these origins, however, the next two hundred years saw a blameless decline into respectability, all taint of romance erased, in a family progress that took the Milbankes from Scottish exile by way of aldermanic and mayoral office in Newcastle to a baronetcy and a safe seat in Parliament.

It was Charles II who granted the title to the first Sir Mark Milbanke in 1661, and over the next century the Milbankes’ influence was consolidated in the network of alliances and marriages that inevitably underpinned eighteenth-century political life. In generation after generation of Sir Marks or Sir Ralphs the same pattern emerged, as the Milbankes of Halnaby Hall married into other northern families, extending their land and connections across the north-east of England, augmenting agricultural interests in one marriage or mineral interests in another before, in the middle of the eighteenth century, forging the key alliance with the powerful Holderness family that gave Stubbs’s 5th Baronet a place in the Commons.