Полная версия

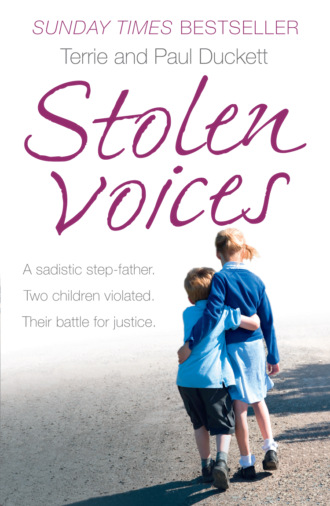

Stolen Voices: A sadistic step-father. Two children violated. Their battle for justice.

‘Hey kids, smile for the camera!’ he said.

Proud in my favourite Superman T-shirt, I gave him my best grin.

After about an hour of deciding, we finally picked our bunnies. Terrie named hers Sooty and mine was Smokey.

Mum couldn’t thank Peter enough. ‘You’re so kind,’ she said repeatedly.

Peter ruffled the top of my head.

‘You’re more than welcome, Cynth.’ He smiled down at us both. ‘The look on these twos faces makes it worth it.’

Peter also gave Mum the things we’d need: a small hutch, sawdust, food, hay and a drinking bottle each. We excitedly set up our new pets’ home that afternoon.

They were so gentle, and soon grew used to us picking them up and stroking them. Every morning I jumped out of bed and went to poke grass through the wire of the cage as a treat. Then I sat and cuddled mine, rubbing my face against Smokey’s silky fur.

A few months after we’d got our new pets, something was wrong with Smokey. He was trying to hop, but looked lopsided. I gently picked him up, but he didn’t want to eat any grass and looked miserable.

‘Muuuuum!’ I cried, calling her to look.

‘Hmm,’ she said, looking upset. ‘He needs to go to a vet.’

We walked to the local vet, carrying Smokey in a box. The vet took one look at his leg and shook his head.

‘He’s broken it,’ he said.

‘What?’ gasped Mum. ‘How did he do that?’

The vet asked if we’d dropped him recently from a height or grabbed his leg in some way. Mum said absolutely not. The vet shrugged and plastered the leg up.

Mum was quiet on the way home. ‘Are you sure you haven’t been too rough with Smokey?’ she asked.

I was completely confused about how Smokey had done this. I kept thinking, maybe it was something I’d done.

My first day at school was traumatic as I hated leaving Mum. The thought of spending all day long without her was too hard and I cried so much in the classroom she had to come and get me. On the second day I was given a pedal bike to race around on in the playground, but when no teachers were looking I pedalled straight out of the gate and home.

‘What’re you doing here?’ asked Mum, her eyebrows shooting up to her hairline.

‘I don’t like school,’ I said simply.

She let me have that afternoon off, but in the morning I was back there. I found it hard to make friends and preferred sitting under a tree or hanging out in the dinner hall, instead of playing tag, or hopscotch or skipping.

My name didn’t do me any favours either. ‘Duckett, Duckett, there’s a hole in my bucket,’ kids chanted in the playground if I did dare show my face.

Kids always found it easy to be mean about me. From my scuffed shoes to my second-hand uniform that didn’t fit properly. Even the two slices of bread and butter I brought for lunch made kids laugh.

‘Is that it?’ taunted one little boy, waving a packet of crisps and a Wagon Wheel at me, as he tore off the plastic wrapper of the chocolate biscuit and stuffed it into his mouth.

‘Mmmhmm!’ he smiled, chomping into the chocolate.

I looked at my soggy white bread and nibbled it miserably. At least I’m not going to be a fat fucker, I thought to myself.

Mum always did her best, but you don’t get a lot of choice when you don’t have money. Thankfully I started getting free school dinners and quickly learned that making friends with the dinner ladies was the way forward. I loved any food. Lumpy custard with the skin on top was a treat to me.

‘Can I have more, please?’ I beamed gratefully, as an extra spoonful slopped on my plate.

‘You’re a good boy,’ said the kindly dinner lady. When no one was around I’d get slipped an extra biscuit too; coconut ones with a cherry on top were my favourite.

Having dinner ladies as allies made up for the fact I didn’t have many others. While the girls always refused to let me play kiss chase, teachers were more likely to appreciate the nice side of me. I could think up things to get myself out of most sticky situations too.

One escape from school and home was my Nan and Pap’s. It was always warm and welcoming, full of hugs, kisses and food, unlike our own. Here I felt loved and normal.

Pap had worked in a shoe factory all his life while Nan kept the house, but she used to tell us all her stories about life in the munitions factory, or when she watched Coventry burning down in a huge bombing raid while close by in the park called ‘The Racecourse’.

I could tell Nan loved me by the way her face softened as she looked at me, and how she looked after me and made sure I was never hungry in her house.

‘We need to fatten you up, Paul,’ she’d frown worriedly. ‘You’re all skin and bone.’

Nan piled my plate high with favourites like bacon and onion roly-poly, or a dish that was pastry over meat, gravy and veg; I never knew what that was called. Ground rice for afters. Me and Terrie would eat until our stomachs hurt. And Pap was a whiz at making wine; he’d joke he could make anything from the sole of his shoe to potato, raspberry, rose hip, blackberry or any fruit he laid his hands on.

Mum adored her parents as much as we did. Sitting around that table with all of them was the place I felt safest in the world. One person who never came join us there, however, was Dad – something both me and Terrie were glad about.

Dad’s own parents, Nin and Bill Duckett, didn’t have any more patience for us than he did. They lived just up the road from Nan and Pap, but they couldn’t be any more different. When we popped around there we often saw our cousins Nicky and Claire, Dad’s sister Ruth’s kids, but we all stayed out of Pap’s way. He sat by himself in the living room, barking orders at Nan for food or drink. Nan had a terrible temper, too; however, she would at least give us a biscuit when we arrived and she never ever left us alone with Pap Duckett either. Not for a single second.

At the end of November 1979, Dad came home from another working jaunt. For once he came through the door with a proper grin on his face.

‘We’re going to South Africa on holiday,’ he announced. ‘It’ll be for four weeks over Christmas.’

We both jumped up and down with real excitement. This wasn’t something the likes of our family ever did. It seemed too good to be true!

We flew out to Johannesburg and caught a train to Kimberley. It was all scary yet exciting. We stayed with Dad’s friends Kevin and Sylvia, who had two kids, James and Anne, a bit younger than us. They showed us the sights, including a diamond mine that completely captured my imagination as we watched the glinting metal sparkle on conveyor belts through metal fences.

Despite being on holiday, Dad was meticulous with time keeping. He was like this at home and now we were away he arranged a very strict schedule. We were up every day for breakfast at 7.30 a.m. on the dot, then out the door by 8 a.m. Dad would time how long everything took. While visiting a museum about the Afrikaaners Dad tapped his watch at the entrance and looked us all individually in the eye.

‘You have precisely 40 minutes to look around,’ he said.

It wasn’t just schedules Dad liked to stick to; the way we looked was important too, despite our hand-me-downs.

‘It’s not acceptable for girls to slouch or have dangly bits of hair in front of the face, Terrie,’ he told her, pulling her shoulders back and yanking back her fringe. ‘And when you speak, speak up clear and loudly so we can all hear.’

So her fringe was kept neatly pinned back, and whenever I walked past Dad I’d square my shoulders a little more.

All too soon, we had to go home. Dad was in a foul mood on the trip back. He had been ill most of the holiday. When we arrived back in England, everywhere was covered in snow. Dad didn’t talk all the way home. Terrie and me slept most of the way back. As soon as we arrived home we were sent straight to bed. It was so cold.

In the morning Mum said Dad had gone to Portsmouth for work. A few weeks later, when it was the half-term holiday, Mum told us we were going to go and visit him. We had to catch a coach. My insides just clenched at the thought of a coach. I got terribly car sick on the shortest journey and knew I’d end up throwing up on a two-hour trip.

We packed a small bag and set off. I sat next to Terrie. She seemed miserable.

I tried to cheer her up. I patted the seat with my hand. ‘Look, bum dust.’ I giggled as a cloud of dust erupted from the seat.

She patted her seat, laughing hard. ‘Fat bum dust.’

Soon we were lost in laughter and patting seats, when Mum leaned over from behind.

‘Pack it in, you two,’ she hissed menacingly. ‘Just sit quietly.’

‘Yes Muuuum,’ we chimed in unison, grinning cheekily.

I turned to look at Terrie. She was doing her best not to look at me. I knew all I had to do was catch her eye and she’d start laughing again.

I closed my eyes, trying to sleep, to escape the waves of nausea. I could feel the bile rising just 20 minutes after we set off.

‘Oh, not again, Paul,’ Mum said as I turned green.

She stood up, wobbling and holding onto seats as she made her way to the driver. ‘Excuse me, but my son is going to be sick,’ she said.

The driver half turned around.

‘Oh,’ he said. ‘Right, well, grab that newspaper by the side of my seat and make him sit on it.’

‘Eh? Sit him on the newspaper?’ quizzed Mum with a puzzled look on her face.

The driver gave a laugh. ‘Yeah, I don’t know why, but it does often stop people feeling sick.’

Willing to try anything, Mum picked up a few sheets and came back.

‘Pop this under you, Paul. The driver says it will stop you chucking up.’

She pushed it under my bum. I struggled, thinking I would look silly and not believing for one moment that the paper would make me better. However, the next thing I remember is waking up, having dozed off, the sickness passed as if by magic and I felt much better. When we arrived in Portsmouth we had to stand and wait a few hours before Dad’s friend Gerry picked us up.

‘Sorry, Cynth.’ He looked embarrassed.

He took us to the house where Dad was staying. A few of the construction men rented the place between them. Dad was sitting at the table; he nodded at us both and handed us 50p each. ‘Go and entertain yourselves until six.’

Terrie had to check her watch was wound up and said the right time. We both then turned and walked down the hallway. On the way out we had to walk past a big glass bowl full of 10ps and 50ps. I looked at Terrie and she raised her eyebrow as we both had the same thought: 50p wasn’t going to last us eight hours. We’d be starving by the time we got back. Terrie grabbed us a handful of change each and we scurried out of the door.

Side by side we set off for the seafront. First stop was the sweet shop. We filled little white bags with sherbet pips, jawbreakers, fruit salads and chewy peanuts. Then we walked to the seafront 15 minutes away and sat down and gorged ourselves. Next, we went roaming on the rocks, grabbing tiny crabs with our hands and chasing each other. We took off our shoes and socks, rolled up our trousers and ran along the sea edge, splashing each other with the cold salty water.

‘I’m cold, Terrie.’ I was shivering; I’d got wetter than I had intended. I was also feeling hungry.

‘Me too,’ agreed Terrie.

We sat on a bench and shared some hot chips. Then we spent the afternoon playing in the amusement arcade.

‘Time to go back, Paul,’ Terrie said resignedly, looking at her watch. She knew I felt the same and squeezed my hand harder as we trudged back. This time the house was quiet as we turned up. No yelling; that was good.

But as soon as we walked in, one look at Mum, her face red and swollen with tears, told us the visit wasn’t going well. Terrie led me off to our room and we quickly got changed. Dad took us to his favourite Chinese restaurant for dinner, but told us we were only allowed crab and sweetcorn soup.

As the pretty Chinese waitress showed us to our seats she looked a bit confused. ‘Hello, John,’ she smiled, bowing. ‘And Karen …?’

Mum visibly bristled, glaring at Dad, as we were ushered to our seats with Dad trying to laugh it off.

I’d heard of Karen a few times by now, but I still had no clue who she was.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.