полная версия

полная версияFig Culture

It can not be too strongly urged that American-grown figs be packed and sold under their proper labels and not designated “Smyrna” figs. Careful selection of varieties, skill in growing and curing, and careful, honest packing will in time procure a large market for our figs.

In all the Mediterranean countries the fresh as well as the dried fig is a common article of diet, both nourishing and wholesome, and it is only a question of time when its value will be generally recognized in this country.

FIG CULTURE IN THE GULF STATES.

By Frank S. Earle

The fig is a domestic fruit of prime importance in all the Gulf and South Atlantic States; throughout this region it is a common dooryard tree. Its broad, rich foliage is one of the first things to catch the eye of the Northern visitor and assure him that he is really in the South.

Toward its northern limit the tree is sometimes injured by unusually severe winters, but unless killed to the ground it never fails to produce heavy annual crops. Even severe winter-killing is usually but a temporary loss, as the roots send up vigorous sprouts that bear the following year.

Although the fig is so widely distributed and so universally esteemed for household uses, it is only recently that any attempt has been made in the territory under consideration to utilize it as a commercial product. In the search throughout the South for possible money crops, other than cotton, it is beginning to attract attention, and in this connection a brief statement of our present knowledge as to the growth and possible uses of the fig may be of service.

PROPAGATION

The fig roots easily from cuttings and is usually propagated in this way. Short pieces or even large branches of well-matured wood, cut from the tree at any time during the winter and simply thrust into the soil, will usually take root and make a strong growth the following summer. The well-matured wood is best for making cuttings. One of the most desirable methods is to cut a section bearing a short but thrifty lateral branch from a good-sized limb. The section taken should be 6 or 8 inches long and be entirely buried in the ground, leaving the end of the side branch projecting to form the tree. This is not at all essential, as a straight cutting will usually root and grow readily, but it is desirable, as the buried cross section holds the cutting firmly in the ground and its bulk prevents it from drying out easily. In the coast region cuttings are often planted in August with good results. In this case the leaves should be removed. It is advisable to plant the cutting where the tree is to stand, as fig roots are easily injured by transplanting. Little is gained in growth by planting rooted trees, but when such are used both roots and tops should be heavily pruned when planted, to secure a satisfactory growth.

Sometimes it is advisable to plant the cuttings in the nursery and to keep them there for three years before removing them to their permanent location, as winter protection can be more easily given them. After the trunk of the fig is three years old it is much less easily injured by cold. This practice would seem to be of doubtful value, since young figs are more often injured by late frosts after growth has started in the spring than by the greater cold of midwinter when they are dormant. Figs can be grafted without difficulty, but it is seldom done in the south.

SOIL AND LOCATION

The fig will grow in almost any location, but it attains its highest development on a rich, moist, but well-drained soil, that contains abundant humus.

A plentiful supply of lime, phosphoric acid, and potash is also needed, and if not contained in the soil must be supplied by fertilization. The best conditions for fig growth are found in the bottoms and hammocks rather than in the sandy uplands, though many fine specimens can be found in either location. In planting for home use it is advisable to plant the trees near the house and about the farm buildings, for they always thrive in such locations, while many failures have been made in attempting to establish them under orchard conditions, especially in the light soils of the “piney woods” region. It is not easy to account for these failures, since the old dooryard trees are so universally healthy and thrifty, though growing without care or attention. Several causes can be cited that may contribute to the result, but all seem insufficient to account fully for the facts observed. There must be some undetected factor that contributes to the almost universal superiority of dooryard over orchard-grown fig trees in the Gulf States.

One of the most obvious difficulties in establishing a fig orchard arises from the fact that the young trees are tender and easily injured by the cold. Figs start very early in the season, and the frequently occurring spring frosts often catch them in quite vigorous growth. This does no great harm to old trees; though the young leaves are killed, they soon push out again, and as the principal crop of fruit is borne on the new wood the crop is not much injured. With young trees, however, it is different, as the tissues of the trunk are softer. Fine, thrifty trees of one or two years’ growth are killed to the ground by a slight freeze after their spring growth has started. They may start again from the root, but their vitality is injured and they do not seem to fully recover. Such trees at 3 or 4 years old are often no larger than after the first summer’s growth. Young trees also suffer much more severely than old ones from extreme cold in winter, even when entirely dormant. It would appear that the shelter afforded by buildings and yard fences may sufficiently protect young trees from damage, when in an open space they would be severely injured. Then, if from a dozen cuttings stuck down in such out-of-the-way places only two or three grow, they are seen and remembered, while the failures are forgotten, whereas an orchard row showing a stand of only one-fourth is very unsatisfactory. The dooryard tree usually gets the benefit of ashes and house-slops, and perhaps the wash from the barnyard. These sources of fertility are all beneficial, for the fig is a gross feeder. Its roots are never broken by the plow, which is another great advantage, for the fig has a shallow rooting habit and does not thrive when its feeding roots are disturbed.

In the light soils of the South it is extremely difficult to keep plows and cultivators from running so deep as to do serious injury to fig trees, and the proper cultivation or treatment of a fig orchard is therefore a serious question. Many growers advise against plowing after the first year, but the tree will not thrive if choked with grass and weeds. To keep a large orchard clean with a hoe is no small undertaking. Some advocate heavy mulching to keep down weeds, and that is doubtless often advisable, but the hard, clean-swept southern dooryard seems to suit the root habit of the fig better than any system of cultivation yet devised. Another point to be considered is that the fig suffers severely from root knot when planted in the fields where vegetables or cowpeas have been grown, as the nematodes causing this trouble multiply in the roots of all such crops.

In planting a fig orchard care should be taken to select new land that is known to be free from these pests.

The fig has a spreading habit of growth and when old requires considerable room. As the cuttings cost but little, it is well to plant rather closely, with the expectation of thinning out the trees when necessary. With 200 trees to the acre the earlier crops would be double those obtained from a planting of half that number, though doubtless 100 full-grown trees would sufficiently occupy the land. Twelve by 16 is a suitable distance for the trees when young. Removing alternate rows when needed would leave the permanent planting 16 by 24 feet. It is best to plant two or three cuttings at each place, to be sure of a stand. All but the most vigorous can be cut out if more than one starts to grow.

CULTIVATION AND FERTILIZATION

Unquestionably figs should be thoroughly cultivated during the first season. This is necessary to give them a good start, and as the young trees make their largest growth after midsummer it is important to continue the cultivation late in the season. Unless the soil is quite rich some fertilizer should be used, as the future of the tree depends largely on its vigor during the first season. An excessive use of stable manure or other nitrogenous fertilizer should be avoided, as the tendency of these is to induce a soft, succulent growth too easily injured by the winter. The “piny-woods” soils are deficient in phosphoric acid, and this should be a prominent ingredient of all fertilizers used in regions where these predominate.

It is not advisable to attempt to cultivate any vegetable crop among fig trees, on account of the danger of increasing root knot, and because such crops are likely to interfere with cultivation at the time when it may be most needed.

The best subsequent treatment for a fig orchard is, to a certain extent, an open question. It is probable that in most locations the best results will be obtained by mulching heavily near the tree with any available material that will hold moisture and keep down the weeds. Pine straw, marsh grass, or planer shavings answer the purpose. The dust from old charcoal pits is sometimes used, and on the coast a mulch of oyster shells is often seen. The slowly decomposing shells probably act to some extent as a fertilizer, since the fig is known to thrive best in strong lime soils. The middle of the rows can be kept clean by a shallow plowing and harrowing without disturbing the mulch and without injury to the roots protected by it. Winter protection of some kind should certainly be provided during the first two or three years, at least to the extent of mounding the dirt or mulch high about the base of the tree in the fall. Protecting the tops with old gunny sacks or pine branches will often prove of great advantage.

Pruning is seldom practiced, except so far as may be necessary to properly shape the young tree, and this is better done in summer by pinching. In case of a freeze, all injured wood should be promptly cut away. It is said that the size of the fruit can be greatly increased by judicious pruning, but, as before stated, it is seldom done.

Figs come into bearing very early. A thrifty growing cutting will often set some fruit the first season, but this seldom matures. When the tree does not winterkill, a little fruit may be expected the second season, and by the third the crop should be of some importance.

INSECT ENEMIES AND DISEASES

The fig is usually spoken of as being comparatively free from insect enemies, and the literature of its diseases, of which there are a number, is scanty. It is probably true that in most localities it is less frequently injured from these causes than are other fruit trees.

Among the diseases reported from the South the one causing most widespread injury is doubtless root knot.

FIG-TREE BORER

A longicorn beetle, Ptychodes vittatus, has caused considerable injury at some points in Louisiana and Mississippi by burrowing into the trunk and larger branches. In reply to inquiries regarding this insect, Director W. C. Stubbs, of the Louisiana Experiment Station, says:

The damage done in Louisiana is to a large extent conjectural. In our groves we have lost several trees temporarily, all being bored into by this borer. They, however, start up again quickly from the roots and soon replace the injured trees. We have had no remedy against this invasion except to dig it out while very young with a penknife. We have tried various insecticides without any apparent results.

FIG-LEAF MITE

A browning and subsequent premature falling of the leaves, caused by the work of a minute mite, is reported as rather common in Florida by Mr. H. J. Webber, of the Subtropical Laboratory. It has not been studied.

Mr. Ellison A. Smith, jr., botanist and entomologist of South Carolina Experiment Station, has published a list1 of insects observed feeding on ripe figs, but he does not mention any that injure the tree.

ROOT KNOT

This disease is caused by a microscopic nematode or true worm, Heterodera radicola,2 that infests the soft fibrous roots causing small galls or swellings. When present in sufficient numbers it causes the death of the roots and the consequent starvation and death of the tree. It is by no means confined to the fig, but attacks the roots of many other fruit and ornamental trees and shrubs and is especially injurious to many garden vegetables and farm crops.3 This pest thrives best in moist sandy soils, and is troublesome throughout the entire coast region.

No effective remedy is known when a tree is once infested, hence the necessity for planting on land known to be free from the pest, and the importance of not growing vegetables between the trees that will act as a nurse crop for the disease.

Neal recommends thorough drainage of the land and the application of tobacco dust mixed with unleached ashes or lime as the most promising remedial measures. He advises against the excessive use of ammoniacal manures as producing a soft, succulent root growth favorable to the growth of the nematode. (See Bulletin No. 20, previously cited.)

FIG-LEAF RUST

Brown spots frequently appear on the foliage during the summer, and, if numerous, cause the leaves to fall prematurely. These spots are caused by a true rust fungus, Uredo fici Cast. It occurs quite frequently widely, and abundantly, but as it usually does not develop enough to be noticeable until after the crop is ripe, it seems to do but little harm. No attempt has been made to find a remedy.

FIG CERCOSPORA

A somewhat similar injury to the leaves is known in Europe, caused by an entirely different fungus, Cercospora bolleana (Thum) Sacc. It had not been observed in this country until the summer of 1895, when it was found abundantly in Mississippi by S. M. Tracy. A cercospora, probably the same species, is also reported from Florida by H. J. Webber. It probably occurs quite commonly, but has been overlooked, its injuries being confounded with those caused by the Uredo.

DIE BACK

A dying of the young shoots in the fall and early winter is sometimes noticed. This occurs before they can have been injured by severe cold and its cause is not known. It usually occurs in feeble trees, those injured by previous winter killing or perhaps those suffering from root knot. A similar trouble is noted by A. F. Barron, of Chiswick, England, (The Garden, June 20, 1891, p. 577). He finds it occurring in trees grown in pots, and says it is there seldom noticed in trees growing out of doors.

ROOT ROT

The fungus Ozonium auricomum Lk., which causes a root rot of cotton and of many other plants and trees, has been reported upon the fig,4 but the extent of damage caused by it is not known. Several other species of fungi are known to occur on the fig, but none of them can be classed as disease-producing organisms.

VARIETIES

Much confusion exists in the naming of fig varieties. They were first introduced by the early French and Spanish settlers, and there have been more or less frequent importations since. Trees from these various sources have been known under many local names, and it is probable that there are now many more names recorded than we have varieties in cultivation. On the other hand, distinct varieties are often met with that can not be named from published descriptions. In Louisiana and Mississippi it is safe to say that nine-tenths of all the figs grown are of the Celeste variety. This is sometimes written Celestial, but among growers it is uniformly known as Celeste. The tree is hardy and very fruitful. The fruit is small, but it is one of the best in quality. When ripe it is a light yellowish brown, tinged with violet. The flesh is light red, delicate in texture, and very sweet and rich. A number of other varieties occur, but they are known under local names, such as “black fig” or “Spanish fig.” More attention has been paid to nomenclature and to the planting of different varieties in other parts of the South, but the Celeste is the favorite in nearly all localities.

Some interesting papers on figs were read at the meeting of the American Pomological Society, held in Florida in 1889, and in the published proceedings of the meeting the following 18 varieties are catalogued among the fruits recommended by the society.

List of figs recommended by American Pomological Society

Alicante; Angelique – synonym, Jaune Hative; Brunswick; Blue Genoa; Black Ischia; Brown Smyrna; Celeste; Green Ischia – synonyms, White Ischia, Green Italian; Lemon; Violet, Long; Violet, Round; Nerii; Pregussata; White Adriatic; White Marseillaise; White Genoa; Superfine de la Sausaye; Turkey – synonym, Brown Turkey.

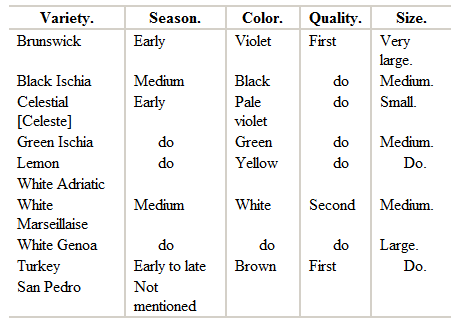

On comparing this list with 11 others furnished by nurserymen and writers on the fig, and taken at random from Texas, Louisiana, Georgia, and Florida sources, we find 14 of these names occurring more or less frequently. Four are not mentioned at all, while 13 additional names appear, making a total of 31 varieties in the 12 lists. Celeste and Brown Turkey lead, being mentioned 11 times each; Adriatic, Lemon, and Brunswick come next, each occurring 8 times. White Marseillaise is mentioned 7 times; White Genoa and Green Ischia, 6 times; Black Ischia, 5 times; and San Pedro, which is not in the American Pomological Society’s list, occurs 4 times. We may perhaps conclude that these 10 varieties are the most generally grown in the South, but some of them are to be considered as nurserymen’s recent introductions from California, rather than as varieties in general use. They are characterized in the Pomological Society’s list as follows:

Other lists agree in describing both White Adriatic and San Pedro as very large white figs of the best quality and very desirable where they succeed, but as being tender and nonfruitful in many locations. Celeste, Brown Turkey, and Brunswick are more uniformly commended for hardiness, fruitfulness, and general utility than any others.5

USES

At present figs are mostly used for household purposes, comparatively few being prepared for market. They are eaten fresh from the tree or are served on the table with sugar and cream. They can also be stewed and made into puddings and pies, and when canned or preserved they make an acceptable table delicacy throughout the year. On first tasting fresh figs many people are disappointed and think they will not care for them, but on further acquaintance nearly everyone learns to like them. If picked at all green the fig exudes a milky, acrid juice that has a rank, disagreeable flavor. When fully ripe this disappears, and in learning to eat figs one should choose only the ripest specimens. The beginner will find eating them at the table with plenty of sugar and cream a pleasant introduction. It is needless to commend this method to those who are acquainted with it.

For canning, figs should be picked when still firm enough to hold their shape. To secure the best results they require the use of more sugar than do some other fruits. If undersweetened they seem tasteless and lacking in quality. The amount of sugar used and the method of procedure vary greatly in different households. A pound of sugar to 3 or 4 pounds of fruit would probably suit most tastes, though some prefer the regular “pound for pound” preserve. Ginger root or orange peel is sometimes added to give variety of flavoring, and figs are often made into sweet pickles by adding spices and vinegar. Figs are sometimes peeled before canning, and this is considered to increase their delicacy of flavor. More frequently, however, they are cooked unpeeled and with the stems on, just as they come from the tree. They hold their shape better and look more attractive when treated in this way, and the difference in flavor, if any, is very slight.

Figs are occasionally dried for household use, but as they ripen at the South during the season of frequent summer showers, this is so troublesome that it is not often attempted. A nice product could doubtless be made by use of fruit evaporators, but these are seldom used far South.

In speaking of home uses for the fig, its value as food for pigs and chickens should not be forgotten. Both are very fond of them, and on many places the waste figs form an important item of their midsummer diet. In fact, no cheaper food can be grown for them.

MARKETING FRESH FIGS

Ripe figs are very perishable. To be marketed successfully they must be handled with great care. It is best to pick them in the morning, while still cool. They should be taken from the tree with the stem attached – great care being exercised not to bruise them in handling – and placed in small, shallow baskets, in which they are to be marketed. In large packages their weight will bruise them badly. The ordinary quart strawberry basket crate is a suitable package for marketing figs. They will carry better, however, in flat trays, holding but a single layer. This form of package is especially desirable for the larger varieties. Figs should hang on the tree until quite ripe and develop their full sweetness and flavor, but in this condition they are soft and perishable and must be consumed at once. For marketing at a distance it is necessary to pick them while still quite firm. This is unfortunate, for though they will soften and become quite edible, they will lack the fine quality of tree-ripened fruit. This fact will always be an obstacle to the successful introduction of the fresh fig into distant markets. When picked in right condition the fruit will keep from twenty-four to thirty-six hours at the ordinary temperature and may be shipped short distances by express. Figs ripen in midsummer when the weather is hottest, and this is one reason why they are so difficult to handle. Like other fruits they will keep longer at lower temperatures. They do well under refrigeration, and by using refrigerator cars it is quite possible to put them on the more distant Northern markets in good condition. This has been done experimentally in connection with other fruit shipments, but it is not often attempted. Fresh figs are not known or appreciated in Northern markets, and consequently the demand is too limited to encourage shipments. It seems doubtful if the distant shipment of fresh figs will ever become a profitable business. The fruit is more perishable than any other that is generally marketed. It can be handled only by the most careful and experienced persons, and even then it is not in a condition to show its best quality. Ripening in midsummer, when the Northern markets are crowded with many well-known fruits, and not being specially attractive to the eye, fresh figs would at best gain favor slowly. The fact that many people do not care for them at the first would be another obstacle in the way of their popularity. Moreover, the fig is a tedious crop to handle, when in proper condition for market. It is necessary to pick the trees over carefully every day during the season, or much fruit will be overripe. With large trees, this involves much labor; the acrid juice of the immature figs eats into the fingers of the pickers and packers, while rainy weather occasions heavy loss by the cracking of the fruit, which renders it unfit for market.

Notwithstanding these drawbacks, a limited demand would undoubtedly be created if the fig were placed regularly on the market, for many people are very fond of this fruit. It is quite possible that in sections especially adapted to fig culture, and favored with rapid refrigerator transportation, the shipment may become a business of importance. When a regular home market can be found, even at moderate prices, no crop is more profitable, as the trees bear regularly and abundantly. The only hope for such a home market, except in the immediate neighborhood of large cities, is in increased use by canners.