Полная версия

Cops and Robbers: The Story of the British Police Car

Parliament thus effectively framed legislation that trusted the established system, horse-drawn wagons, and prevented the scaring of horses, which were then the backbone of commerce. The country’s legislators put more trust in the behaviour of horses than in the safety of human-designed and built machinery … This seems amusing to modern sensibilities, but perhaps they were right to create these laws, for these early machines weighed an enormous amount, had little in the way of brakes and made all sorts of scary clanking and hissing noises which could spook even the best-trained horse. However, the development of smaller petrol and electric carriages made this law outdated by 1890, and it was this law that was most often tested by pioneer motorists who claimed they could use an Autocar on a standard (horse-drawn) carriage licence rather than the much more restrictive Locomotive Licence. Arnold also claimed this and was convicted of this offence as well as speeding. This Arnold chap is my type of guy. I like to think we would have been friends.

Although the use of motor cars was growing in the 1890s, the horse was king and would effectively remain so (at least in volume terms) until after World War I, which was, like so many conflicts, the catalyst that drove change technically, economically and socially.

The world’s first petrol-powered proper road trip …

Britain’s legislation did not help our nascent car industry to grow, but it also didn’t stop the rest of the world coming to a collective consensus about the fuel of the future. Karl Benz produced the first gasoline-engined car in 1885, and in August 1888, without his knowledge, his wife Bertha made the first ever car journey of significant length using an improved version of his design, to prove its worth to the less-than-confident Benz as well as the world.

Bertha and their two sons, Eugen (15) and Richard (14), travelled from Mannheim to Pforzheim, her place of birth, and although Bertha apparently used a hatpin to unblock a fuel line, she demonstrated the practicality of the gasoline motor vehicle to the entire world – and perhaps should have to put to bed any criticism of women drivers at the same time … Without her daring – and that of her sons – this book might have been about steam-powered police cars!

Left: Portrait of Bertha Benz. Right: Bertha Benz and her sons buy petrol during their long-distance journey in 1888.

Some UK pioneer motorists deliberately challenged the Red Flag Act, believing their new lightweight steam-, electric-or gasoline-powered vehicles should be classed as ‘horseless carriages’ and therefore be exempt from the need for a preceding pedestrian and could be operated using a carriage licence. A case was brought against motoring pioneer John Henry Knight in 1895; he lost and was convicted of using a locomotive without a licence and fined 2 shillings and 6d. However, he had neither a carriage nor a locomotive licence, so the law had two ways to turn, which meant that he was guilty of using a locomotive without a licence whichever decision was made!

Early editions of The Autocar (a weekly magazine, the first edition of which was published on 2 November 1895 and whose cover proclaimed: ‘A journal published in the interest of the mechanically propelled road carriage’) were full of lengthy reports of court proceedings being taken against motoring pioneers for a variety of reasons. Legislators caught up with the reality of mechanical development before the law created any real precedents, and the Red Flag Act was repealed on Saturday 14 November 1896, when the speed limit was raised to 14mph; a fact that was celebrated on the day by an Emancipation Day Run (in which our speeding friend Arnold took part in the very same car in which he had been done for speeding) and which today’s London to Brighton Veteran Car Run (often incorrectly called a race) celebrates.

Sadly, the first recorded automotive road fatality in the UK was also in 1896, when Bridget Driscoll, 44, was killed in the grounds of the Crystal Palace on 17 August. She was walking with her 16-year-old daughter, May, and a friend when she was run over by a Roger-Benz car being driven by Arthur Edsall. At the inquest, Florence Ashmore, a domestic servant, gave evidence that the car went at a ‘tremendous pace’, like a fire engine – ‘as fast as a good horse could gallop’.

The driver, working for the Anglo-French Motor Co., who were part of an automotive exhibition taking place at the Crystal Palace, said that he was doing 4mph when he killed Mrs Driscoll and that he had rung his bell and shouted ‘Stand Back!’ as he approached. However, it was suggested that Mrs Driscoll seemed bewildered in front of the car. She may not have interacted this closely with a motor vehicle before. Who knows? There were then fewer than twenty in the whole of the UK and the public were certainly not educated in how to cross roads safely. Edsall had been driving for only three weeks at the time, and as no licence was required, the fact that he apparently had not been told which side of the road he needed to travel on was overlooked … The case went to court, but with conflicting evidence about the speed and manner of Mr Edsall’s driving, the jury returned an accidental death verdict. Interestingly, there was no outrage in the newspapers at the time, just a sense that it was an unfortunate accident. It would be some years before the press became powerful enough to express outrage in the way that we take for granted today. It’s also worth noting that, although people had been killed by horses or carriages for many years, high-profile autocar accidents did start to bring up some public discussion of these dangerous new machines, which were loved by those who had them and often feared by those unfamiliar with them. For that reason accidents were reported perhaps a trifle more vociferously than they would have been if someone had simply fallen off a horse and broken their neck. It was, after all, the start of the unknown.

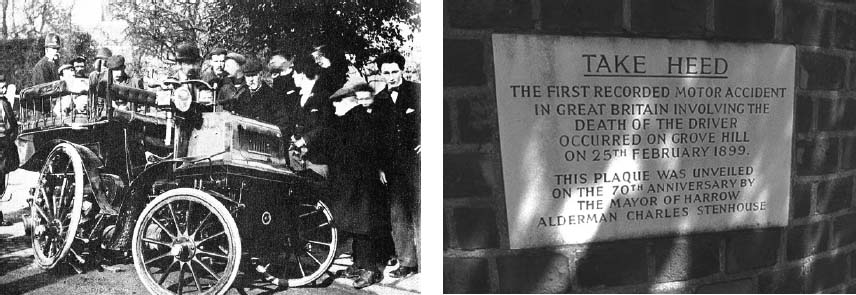

Perhaps ironically, the first death in an autocar accident was during an incident with an International Co. electric vehicle on 12 February 1898, when Mr Henry Lindfield of Brighton tried to stop his vehicle in order that his passenger, his 19-year-old son Bernard, could retrieve his bag, which had fallen off as they descended the hill off Purley Corner, in Croydon. When the brakes were applied the vehicle began to weave, before eventually hitting a post and then a tree, sandwiching poor Henry between the carriage and the tree. Son Bernard was thrown over his father and survived with relatively minor injuries, but, sadly, his father died in hospital the following day. Just over a year later the first fatal accident involving the driver of a petrol motor vehicle was recorded; 31-year-old engineer Edwin Sewell’s 6HP Daimler Wagonette crashed into a wall after a rear wheel collapsed following a rim breakage when the brakes were applied too harshly while descending a steep hill at speed. He died almost instantaneously. At the time he was demonstrating the vehicle to three passengers who were assessing it for possible purchase by their company, the Army and Navy Stores, then a well-known department store. The front-seat passenger, 63-year-old Major James Stanley Richer, was thrown clear of the vehicle with Sewell and suffered such serious injuries that he died three days later in hospital. The other two passengers were injured but survived.

The roadside plaque (unveiled on 25 February 1969) records the site of Britain’s first fatal road accident, on 25 February 1899.

As a result, the UK police started to take cars seriously, and the weight of public pressure – and in some cases outrage – meant that they had to. As far as research can prove, it was the Met that led the way, acquiring a Léon Bollée Voiturette in 1896, or possibly early 1897. The arrival of the Bollée, as it was usually called, is important because it represented the moment when the British police moved from enforcing legislation on motorists to becoming motorists themselves. Quite what those early Met police pioneer drivers would think of today’s high-speed chases on the M25 we shall never know, but to modern eyes the pioneering car does seem almost laughably poor in both performance and engineering terms. At that time the template for what makes an acceptable usable car, as opposed to an experiment down a dead-end avenue of design, was yet to be set, and the Mercedes-badged Daimler that made every other autocar old-fashioned overnight, and so set the car on its course to dominate transportation in developed nations by the early 1920s, would not appear until 1901.

1896 Léon Bollée Voiturette

The birth of the Léon-Bollée Voiturette light autocar goes back to the 1870s, when Amédée Bollée, son of a foundry owner specialising in bells, started making steam vehicles in Le Mans, France, way before the town became part of motor-racing folklore after Renault’s victory in the 1906 French Grand Prix there.

Although Amédée Bollée was a steam enthusiast, he could see the potential in gasoline-engined cars and helped both his sons, Amédée Junior and Léon, design and build them. Léon’s design was immediately successful, although I suspect anyone who ever crashed into anything while sitting on that front-mounted chair may have disagreed! The vehicle was considered fast in its day; even in their early days the police bought the fastest car they could afford, kicking off the arms race between the good and the bad guys earlier than most of us had realised!

Bollée’s design for a very short-wheelbased, 3-seater motor-tricycle, the Voiturette, weighed only 264lbs, used a tubular frame and featured a single back wheel, making it far more stable than having the single wheel at the front. The engine was an air-cooled, horizontal, single-cylinder unit of 650cc that was hung beside the back wheel on the near-side and used a large, heavy flywheel. It featured suction-opened inlet valves and mechanical exhaust valves with plain bronze bearings, hand-lubricated by grease for the main bearings and a splash-lubricated big-end. A tubular con-rod kept the weight down, while hot-tube ignition and a single-jet carburettor were so close to the float chamber that fires were common. The 3-speed transmission was by three virtually unlubricated gears on the end of the crank, which could be meshed with the three layshaft gears. The drive was by flat belt, a mechanism that was commonly used then to drive lathes and other machines in workshops. There was no actual clutch; the mechanical movement of the back wheel tightened or loosened the driving belt so that drive was achieved or neutral was obtained. Full-forward movement of the back wheel applied the belt rim to a stationary brake block. In some ways it was an elegantly simple solution; one fore and aft movement of the rear wheel achieved one of three outcomes. However, the Bollée was apparently quite tricky to actually drive, partly because it featured a small steering wheel on the driver’s right with a handle familiar to traction-engine drivers, which actuated an early rack-and-pinion steering system. Meanwhile, the left hand had to ease the gear stick gingerly back and forth to engage the drive or free it. Turning the spade grip at the top of this lever engaged a gear, and, in order to stop, the lever had to be hastily pulled backwards. I can’t imagine many of my former police colleagues (or myself, for that matter) taking it easily, but perhaps sheer fear would have engendered that on this device …

The Voiturette was powerful for its size and weight, and its low build made it stable, but the short wheelbase made spinning on slippery cobbled roads quite common, and comfort was not a priority because they had no suspension, relying on pneumatic tyres and a C-sprung seat to provide a modicum of relief. However, driven by what we must assume were men made of granite, they dominated their class in early motor races, famously occupying the top four places in the 1896 Paris-Mantes-Paris race, and winning their class in the 1897 Paris-Dieppe race with a time that was 0.6mph faster than the best four-wheeled car. Legendary English racing driver and Le Mans winner S.C.H. Sammy Davis bought an example in 1929 to use in the London to Brighton Veteran Car Run (a Léon Bollée Voiturette was apparently the first car across the line on the original Emancipation Run in 1896) and was pleased to achieve a maximum speed of 19mph when testing it at Brooklands! This would have been impressive in 1896; the first Land Speed Record was recorded in 1898 at 39mph. Amazing to think now how far we have come.

After being developed in the family’s Le Mans workshop, the car was produced in Paris, at 163 Avenue Victor Hugo, and at Le Harve by Diligent et Cie. It’s believed that around 750 units were made; Michelin ordered 200 and the Hon Charles Rolls (we all know who he was) was a customer in 1897. By 1899 new four-wheeled Bollées were being produced, some with much larger 4.6-litre engines, but the marque was bought by UK maker Morris in 1924, who produced the Morris-Léon Bollée until 1931. It finally faded away for good in 1933.

What’s in a name?

Léon Bollée’s tricycle may have been short-lived, but the word he appears to have invented to name it, Voiturette, lived on and became the generally accepted term for a small lightweight car. It comes from the French word for automobile, voiture, and became so ubiquitous that it was used to name a specific Voiturette racing class for lightweight cars with engines of 1.5 litres or smaller. The supercharged Alfa Romeo 158/159 Alfetta that so dominated F1 on its inception was, in fact, originally designed as a Voiturette class racer.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.