полная версия

полная версияEvery Day Life in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

Galloway. Essex Co. (Mass.) Court Records (1681).

Garlits, Garliz, Garlix. Linens made in Gorlitz, Prussian Silesia. There are several kinds in shades of blue-white and brown.

Ghenting. A kind of linen, originally made in Ghent, Flanders. Used for handkerchiefs, etc.

Grisette, Grizet. An inferior dress fabric, formerly the common garb of working girls in France. His doublet was a griset-coat (1700).

Grogam, Grosgrane. A coarse fabric of silk, of mohair and wool, or these mixed with silk; often stiffened with gum. Used for aprons, cloaks, coats, doublets, gowns and petticoats. My watered grogram gown (1649). Grograms from Lille (1672).

Haircloth. Cloth made of hair and used for tents, towels, and in drying malt, hops, etc. Every piece of haircloth (1500). Coal sacks made of hair-cloth (1764).

Hamald, Hamel, Hammells. Homemade fabrics. Narrow hammells. Boston Gazette, June 30, 1735.

Harrateen. A linen fabric used for curtains, bed hangings, etc. Field bedsteads with crimson harrateen furniture (1711). Harrateen, Cheney, flowered cotton and checks (1748). For curtains, the best are linen check harrateen (1825).

Holland. A linen fabric, originally made in Holland. When unbleached called brown holland. A shift of fine holland (1450). Women cover their head with a coyfe of fine holland linen cloth (1617). Fine holland handkerchiefs (1660).

Humanes at 18 d. per yard. Essex Co. (Mass.) Court Records (1661).

Huswives, Housewife's Cloth. A middle grade of linen cloth, between coarse and fine, for family uses. Howsewife's cloth (1571). Neither carded wool, flax, or huswives cloth (1625).

Inkle, Incle, Incle Manchester. A narrow linen tape, used for shoe ties, apron strings, etc. A parcel of paper bound about with red incle (1686).

Jeans. A twilled cotton cloth, a kind of fustian. Jean for my Lady's stockings (1621). White jean (1766).

Kenting. A kind of fine linen cloth originally made in Kent. Canvas and Kentings (1657). Neckcloths, a sort that come from Hamborough, made of Kenting thread (1696).

Kersey. A coarse, narrow cloth, woven from long wool and usually ribbed. His stockings were Kersie to the calf and t'other knit (1607). Trowsers made of Kersey (1664), black Kersie stockings (1602). Thy Kersie doublet (1714). Kerseys were originally made in England. Her stockings were of Kersey green as tight as any silk (1724). Kerseys were used for petticoats and men's clothing.

Lawn, Lane. A kind of fine linen, resembling cambric. Used for handkerchiefs, aprons, etc. A coyfe made of a plyte of lawne (1483). A thin vail of calico lawne (1634), a lawn called Nacar (1578).

Lemanees. Boston Gazette, May 26, 1755.

Linds. A linen cloth. Kinds of linne or huswife-cloth brought about by peddlers (1641).

Linsey, Lincey. In early use a coarse linen fabric. In later use – Linsey-woolsey. Clothes of linsey (1436). Blue linsey (1583).

Linsey-woodsey, Lindsey-woolsey. A fabric woven from a mixture of wool and flax, later a dress material of coarse inferior wool, woven on a cotton warp. Everyone makes Linsey-woolsey for their own wearing (New York, 1670). A lindsey-woolsey coat (1749). A linsey-woolsey petticoat (1777).

Lockram, Lockrum. A linen fabric of various qualities, for wearing apparel and household use. Lockram for sheets and smocks and shirts (1520). Linings of ten penny lockram (1592). His lockram band sewed to his Linnen shirt (1616). A lockram coife and a blue gown (1632).

Lutestrings. A glossy silk fabric. Good black narrow Lute-Strings and Alamode silks (1686). A flowing Negligee of white Lutestring (1767). A pale blue lutestring domino (1768).

Lungee, Lungi. A cotton fabric from India. Later a richly colored fabric of silk and cotton. Wrapped a lunge about his middle (1698). A Bengal lungy or Buggess cloth (1779). Silk lungees. Boston Gazette, June 23, 1729.

Manchester. Cotton fabrics made in Manchester, England. Manchester cottons and Manchester rugges otherwise named Frices (1552). Linen, woolen and other goods called Manchester wares (1704). A very showy striped pink and white Manchester (1777).

Mantua. A silk fabric made in Italy. Best broad Italian colored Mantuas at 6/9 per yard (1709). A scarlet-flowered damask Mantua petticoat (1760).

Medrinacks, Medrinix. A coarse canvas used by tailors to stiffen doublets and collars. A sail cloth, i.e., pole-davie.

Missenets. Boston News-Letter, Dec. 18, 1760.

Mockado. A kind of cloth much used for clothing in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Tuft mockado was decorated with small tufts of wool. It was first made in Flanders and at Norwich, England, by Flemish refugees. A farmer with his russet frock and mockado sleeves (1596). Crimson mochadoes to make sleeves (1617). A rich mockado doublet (1638).

Molecy. 2 yards, 12 s. Essex Co. (Mass.) Probate (1672).

Nankeen. A cotton cloth originally made at Nankin, China, from a yellow variety of cotton and afterwards made at Manchester and elsewhere of ordinary cotton and dyed yellow. Make his breeches of nankeen (1755). His nankeen small clothes were tied with 16 strings at each knee (1774).

Niccanee. A cotton fabric formerly imported from India. Mentioned in the London Gazette in 1712.

Nilla. A cotton fabric from India. There are two sorts, striped and plain, by the buyers called Bengals … used for Gowns and Pettycoats (1696).

Noyals, Noyles, Nowells. A canvas fabric made at Noyal, France. Noyals canvas (1662). Vitry and noyals canvas (1721).

Osnaburg Oznabrig, Ossembrike. A coarse linen cloth formerly made at Osnabruck, Germany. Ossenbrudge for a towell to the Lye tabyll (1555). A pair of Oznabrigs trowsers (1732).

Pack Cloth. A stout, coarse cloth used for packing. Packed up in a bundle of pack cloth (1698).

Padusoy, Padaway. A strong corded or gross-grain silk fabric, much worn by both sexes in the eighteenth century. Padusay was a kind of serge made in Padua and imported into England since 1633 or earlier. A pink plain poudesoy (1734). A laced paduasoy suit (1672). A petticoat lined with muddy-colored pattissway (1704). A glossy paduasoy (1730). A fine laced silk waistcoat of blue paduasoy (1741).

Palmeretts. Boston Gazette, Aug. 22, 1757.

Pantolanes. Essex Co. (Mass.) Court Records (1661).

Pantossam. Essex Co. (Mass.) Court Records (1661).

Paragon. A kind of double camlet used for dress and upholstery in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. 12 yards of water paragon at 5⁄8 and 5 yards of French green paragon at 25/10 (1618). Hangings for a room of green paragon (1678). Black paragon for a gown (1678).

Parisnet, Black and White. Boston News-Letter, Dec. 18, 1760.

Patch. A kind of highly glazed printed cotton, usually in bright-colored floral designs, used for window draperies and bed hangings. Advertised in Boston News-Letter, June 24, 1742. English and India patches. Boston News-Letter, Dec. 18, 1760.

Pealong, White English. Boston Gazette, Mar. 30, 1734.

Pellony. Essex Co. (Mass.) Court Records (1680).

Penistone, Penniston. A coarse woolen cloth made at Penistone, Co. Yorkshire, England, used for garments, linings, etc. Clothes called pennystone or forest whites (1552). Red peniston for petticoats (1616).

Pentado. Essex Co. (Mass.) Court Records (1680).

Perpetuana. A durable woolen fabric manufactured in England from the sixteenth century, similar to everlasting, durance, etc. The sober perpetuana-suited Puritan (1606). A counterpane for the yellow perpetuana bed (1648).

Philip. A kind of worsted or woolen stuff of common quality. 12 yards of philip and cheney for a coat for Mrs. Howard (1633). My red bed of Phillip and China (1650).

Pocking Cloth. Essex Co. (Mass.) Court Records (1674).

Poldavy, Poledavis. A coarse canvas or sacking, originally woven in Brittany, and formerly much used for sailcloth. A canvas of the best poldavie (1613). Pole-Davies for sails (1642).

Pompeydones. Boston Gazette, Aug. 22, 1757.

Poplin. A fabric with a silk warp and worsted weft, having a corded surface. Lined with light colored silk poplin (1737).

Porstotana. Essex Co. (Mass.) Court Records (1680).

Prunella, Prenella. A strong stuff, originally silk, afterwards worsted, used for clergymen's gowns, and later for the uppers of women's shoes. Plain black skirts of prunella (1670).

Rash. A smooth-surfaced fabric made of silk (silk rash) or worsted (cloth rash). A cloak of cloth rash (1592). My silk rash gown (1597). He had a cloak of rash or else fine cloth (1622).

Ratteen, Rating. A thick twilled woolen cloth, usually friezed or with a curled nap, but sometimes dressed; a friezed or drugget. A cloak lined with a scarlet Ratteen (1685). A ratteen coat I brought from Dublin (1755). A brown ratteen much worn (1785).

Romal. A silk or cotton square or handkerchief sometimes with a pattern. 12 pieces of Romals or Sea Handkerchiefs (1683). There are three sorts, silk Romals, Romals Garrub and cotton Romals (1696).

Russel. A woolen fabric formerly used for clothing, especially in the sixteenth century, in various colors; black, green, red, grey, etc. A woman's kertyl of Russell worsted (1552). A black russel petticoat (1703).

Sagathy, Sagatheco. A slight woolen stuff, a kind of serge or ratteen, sometimes mixed with a little silk. A brown colored sagathea waistcoat and breeches (1711).

Sarsenet, Sarcenet. (Saracen cloth). A very fine and soft silk material made both plain and twilled, in various colors. Curtains of russet sarsenet fringed with silk (1497). A doublet lined with sarcenet (1542). Some new fashion petticoats of sarcenett (1662). A scarlet coat lined with green sarcenet (1687).

Satinette, Satinet. An imitation of satin woven in silk or silk and cotton. A cloth-colored silk sattinet gown and petticoat (1703). A thin satin chiefly used by the ladies for summer nightgowns, &c. and usually striped (1728).

Satinisco. An inferior quality of satin. His means afford him mock-velvet or satinisco (1615). Also there were stuffs called perpetuano, satinisco, bombicino, Italicino, etc. (1661).

Say. Cloth of a fine texture resembling serge; in the sixteenth century sometimes partly of silk and subsequently entirely of wool. A kirtle of silky say (1519). A long worn short cloak lined with say (1659). Say is a very light crossed stuff, all wool, much used for linings, and by the Quakers for aprons, for which purpose it usually is dyed green (1728). It was also used for curtains and petticoats.

Scotch Cloth. A texture resembling lawn, but cheaper, said to have been made of nettle fibre. A sort of sleasey soft cloth … much used for linens for beds and for window curtains (1696).

Sempiternum. A woolen cloth made in the seventeenth century and similar to perpetuana. See Everlasting.

Shag. A cloth having a velvet nap on one side, usually of worsted, but sometimes of silk. Crimson shag for winter clothes (1623). A cushion of red shag (1725).

Shalloon. A closely woven woolen material used for linings. Instead of shalloon for lining men's coats, sometimes use a glazed calico (1678).

Sleazy. An abbreviated form of silesia. A linen that took its name from Silesia in Hamborough, and not because it wore sleasy (1696). A piece of Slesey (1706).

Soosey. A mixed, striped fabric of silk and cotton made in India. Pelongs, ginghams and sooseys (1725).

Stammel. A coarse woolen cloth, or linsey-woolsey, usually dyed red. In summer, a scarlet petticoat made of stammel or linsey-woolsey (1542). His table with stammel, or some other carpet was neatly covered (1665). The shade of red with which this cloth was usually dyed was called stammel color.

Swanskin, Swanikins. A fine, thick flannel, so called on account of its extraordinary whiteness. The swan-skin coverlet and cambrick sheets (1610).

Tabby. Named for a quarter of Bagdad where the stuff was woven. A general term for a silk taffeta, applied originally to the striped patterns, but afterwards applied also to silks of uniform color waved or watered. The bride and bridegroom were both clothed in white tabby (1654). A child's mantle of a sky-colored tabby (1696). A pale blue watered tabby (1760). Rich Morrello Tabbies. (Boston Gazette, March 25, 1734).

Tabling. Material for table cloths; table linen, Diaper for tabling (1640). 12 yards tabling at 2/6 per yard. Essex Co. (Mass.) Probate (1678).

Tamarine. A kind of woolen cloth. A piece of ash-colored wooley Tamarine striped with black (1691).

Tammy. A fine worsted cloth of good quality, often with a glazed finish. All other kersies, bayes, tammies, sayes, rashes, etc. (1665). A sort of worsted-stuff which lies cockled (1730). Her dress a light drab lined with blue tammy (1758). A red tammy petticoat (1678). Strain it off through a tammy (1769).

Tandem. A kind of linen, classed among Silesia linens. Yard wide tandems for sale (1755). Quadruple tandems (1783).

Thick Sets. A stout, twilled cotton cloth with a short very close nap: a kind of fustian. A Manchester thickset on his back (1756).

Ticklenburg. Named for a town in Westphalia. A kind of coarse linen, generally very uneven, almost twice as strong as osnaburgs, much sold in England. About 1800 the name was always stamped on the cloth.

Tiffany. A kind of thin transparent silk; also a transparent gauze muslin, cobweb lawn. Shewed their naked arms through false sleeves of tiffany (1645). Black tiffany for mourning (1685).

Tow Cloth. A coarse cloth made from tow, i.e., the short fibres of flax combed out by the hetchell, and made into bags or very coarse clothing. Ropes also were made of tow.

Tobine. Probably a variant of tabby. With lustre shine in simple lutestring or tobine (1755). Lutestring tobines which commonly are striped with flowers in the warp and sometimes between the tobine stripes, with brocaded sprigs (1799). A stout twilled silk (1858).

Trading Cloth, see Duffell.

Turynetts. Boston Gazette, Aug. 22, 1757.

Venetians. A closely woven cloth having a fine twilled surface, used as a suiting or dress material.

Villaranes. Essex Co. (Mass.) Court Records (1661).

Vitry, Vittery. A kind of light durable canvas. Vandolose [vandelas] or vitrie canvas the ell, 10s. (1612). Narrow vandales or vittry canvas (1640).

Water Paragon, see Paragon.

Witney, Whitney. A heavy, loose woolen cloth with a nap made up into blankets at Witney, Co. Oxford, England. Also, formerly, a cloth or coating made there. True Witney broadcloth, with its shag unshorn (1716). Fine Whitneys at 53 s. a yard, coarse Whitneys at 28 s. (1737).

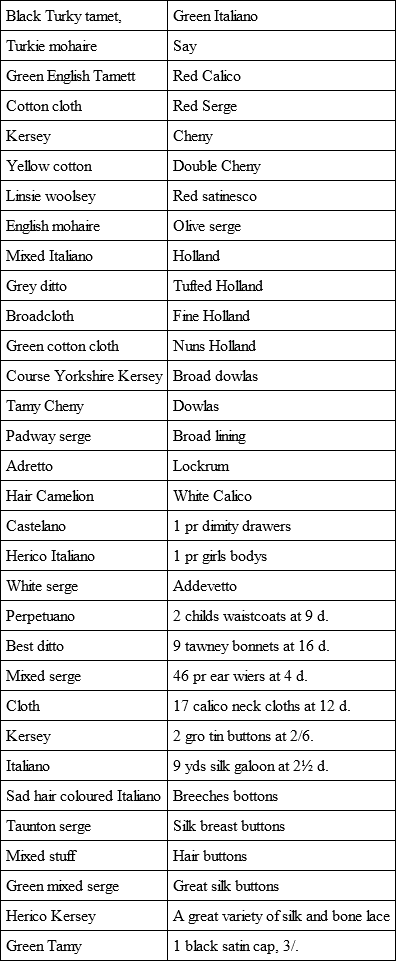

In the Inventory of the Estate of Henry Landis of Boston, shopkeeper, taken Dec. 17, 1651, the following fabrics are listed, viz.:

CHAPTER VI

Pewter in the Early Days

In the spring of 1629, when the Secretary of the Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England was preparing a memorandum of materials to be obtained "to send for Newe England" in the ships that sailed on April 25th of that year, among the fabrics and food stuffs, the seed grain, potatoes, tame turkeys, and copper kettles of French making without bars of iron about them, were listed brass ladles and spoons and "pewter botles of pyntes & qrts." The little fleet reached Naumkeck (now Salem) on June 30th, and on its return voyage, a month later, Master Thomas Graves, the "Engynere," expert in mines, fortifications, and surveys, who had come over with Governor Endecott the previous year, sent home a report to the Company in which he listed "such needefull things as every Planter doth or ought to provide to go to New-England," including victuals for a whole year, apparel, arms, tools, spices, and various household implements, among which appear "wooden platters, dishes, spoons and trenchers," with no mention of pewter. The records of the Company make mention of carpenters, shoemakers, plasterers, vine planters, and men skillful in making pitch, salt, etc., but nowhere does the trade of the pewterer appear.

Pewter did not come into general use among the more prosperous farmers in England until about the middle of the sixteenth century and then only as a salt – a dish of honor, or three or four pieces for use on more formal occasions. It was the wooden trencher that was commonest in use in all middle-class families until well after the year 1700, and this was true both in New England and Old England. In homes where the shilling was made to go as far as possible, the wooden trencher, like the homespun coat, lingered in use for a century later. At least one family in Essex County, Massachusetts, was still using its wooden plates of an earlier period as late as 1876, when the menfolk left home to work for two or three days in the early fall on the thatch banks beside Plum Island river. And this happened in a comfortably situated, but thrifty, family. The rough usage given the common tableware in the crude camp by the marshes had taught the housewife the desirability of bringing down from the chest in the attic, at least once a year, the discarded wooden plates used in her childhood.

Pewter appears early in the Massachusetts Colony in connection with the settlement of estates of deceased persons. By means of the detailed inventories taken at such times, it is possible to reconstruct with unquestioned accuracy the manner in which the homes of the early settlers were furnished, and by means of this evidence it is possible to show that the hardships and crudities of the first years were soon replaced by the usual comforts of the English home of similar station at the same time. The ships were crossing the Atlantic frequently and bringing from London, Plymouth or Bristol, to the new settlements, all manner of goods required for sale in the shops that had been set up in Boston, Salem and elsewhere.

In 1635 the widow Sarah Dillingham died at Ipswich, leaving a considerable estate. Among the bequests were a silver bowl and a silver porringer, and the inventory shows 40½ pounds of pewter valued at £2.14.0.

In 1640, Bethia Cartwright of Salem bequeathed to her sister, Mary Norton, three pewter platters and a double saltcellar and to a nephew she gave six spoons and a porringer.

In 1643, Joseph, the eldest son of Robert Massey of Ipswich, was bequeathed by his father, four pewter platters and one silver spoon. Benjamin, another son, was to receive four pewter platters and two silver spoons, and Mary, a daughter, received the same number as did Joseph.

In 1645, Lionell Chute died in Ipswich. His silver spoon he bequeathed to his son James. It was the only piece of silver in the house. Of pewter, he had possessed fourteen dishes, "small and great," eleven pewter salts, saucers and porringers, two pewter candlesticks and a pewter bottle.

The widow, Mary Hersome of Wenham, possessed in 1646 one pewter platter and two spoons. The same year Michael Carthrick of Ipswich possessed ten pewter dishes, two quart pots, one pint pot, one beaker, a little pewter cup, one chamber pot and a salt. In 1647, William Clarke, a prosperous Salem merchant, died possessed of an interesting list of furniture; six silver spoons and two small pieces of plate; and the following pewter which was kept in the kitchen – twenty platters, two great plates and ten little ones, one great pewter pot, one flagon, one pottle, one quart, three pints, four ale quarts, one pint, six beer cups, four wine cups, four candlesticks, five chamber pots, two lamps, one tunnel, six saucers and miscellaneous old pewter, the whole valued at £7. The household also was supplied with "China dishes" valued at twelve shillings. John Lowell of Newbury, in 1647, possessed three pewter butter dishes. John Fairfield of Wenham, the same year, had two pewter fruit dishes and two saucers; also four porringers, a double salt, one candlestick and six spoons, all of pewter. His fellow-townsman, Christopher Yongs, a weaver, who died the same year, possessed one bason, a drinking pot, three platters, three old saucers, a salt and an old porringer, all of pewter and valued at only ten shillings. There were also alchemy spoons, trenchers and dishes and a pipkin valued at one shilling and sixpence.

When Giles Badger of Newbury died in 1647 he left to his young widow a glass bowl, beaker and jug, valued at three shillings; three silver spoons valued at £1, and a good assortment of pewter, including "a salt seller, a tunnell, a great dowruff" and valued at one shilling. The household was also furnished with six wooden dishes and two wooden platters. The inventory of the estate of Matthew Whipple of Ipswich totalled £287.2.1, and included eighty-five pieces of pewter, weighing 147 pounds and valued at £16.9.16. In addition, there were four pewter candlesticks valued at ten shillings; two pewter salts, five shillings; two pewter potts, one cup and a bottle, four shillings and sixpence; one pewter flagon, seven shillings; twenty-one "brass alchimic spoones" at four shillings and four pence each; and nine pewter spoons at eighteen pence per dozen. The inventory also discloses one silver bowl and two silver spoons valued at £3.3.0; six dozen wooden trenchers, valued at three shillings; also trays, a platter, two bowles, four dishes, and "one earthen salt."

The widow Rebecca Bacon died in Salem in 1655, leaving an estate of £195.8.6 and a well-furnished house. She had brass pots, skillets, candlesticks, skimmers, a little brass pan, and an excellent supply of pewter, including "3 large pewter platters, 3 a size lesse, 3 more a size lesse, 3 more a size lesse, £1.16; 1 pewter bason, 5s; 6 large pewter plates & 6 lesser, 9s; 19 Pewter saucers & 2 fruite dishes, 11s, 6d; 1 old Pewter bason & great plate, 3s; 2 pewter candlesticks, 4s; 1 large pewter salt & a smal one; 2 pewter porringers, 3s.6d; 1 great pewter flagon; 1 lesser, 1 quart, 2 pints & a halfe pint, 13s; 2 old chamber pots & an old porringer, 3s." She also died possessed of "1 duble salt silver, 6 silver spones, 1 wine cup & a dram cup of silver, both £6."

The Rev. James Noyes of Newbury, when he died in 1656, was possessed of an unusually well-equipped kitchen, supplied with much brass and ironware and the following pewter, viz.: "on one shelfe, one charger, 5 pewter platters and a bason and a salt seller, £1.10.0; on another shelfe, 9 pewter platters, small & great, 13 shillings; one old flagon and 4 pewter drinking pots, 10 shillings." No pewter plates or wooden trenchers are listed.

In other estates appear some unusual items, such as: a pewter brim basin, pewter cullenders, pewter beer cups, pewter pans, pewter bed pans, and a mustard pot.

The trade of the pewterer does not seem to have been followed by many men in New England during the seventeenth century. The vessels were bringing shipments from London and moreover, the bronze moulds used in making the ware were costly. Pewter melted easily and frequently required repairing, and it was here that the itinerant tinker or second-rate pewterer found employment. The handles of pewter spoons broke easily, and a spoon mould was a part of the equipment of every tinker. The earliest mention we have noted of the pewterer practising his trade in New England is one Richard Graves of Salem. He was presented at a Quarterly Court on February 28, 1642-43 for "opression in his trade of pewtering" and acquitted of the charge. Then he was accused of neglecting to tend the ferry carefully, so it would seem that pewtering occupied only part of his time. This he acknowledged, but said that he had not been put to it by the Court and also that it was necessary to leave the ferry when he went to mill, a quite apparent fact. He seems to have been a somewhat reckless fellow in his dealings with neighbors, for he was accused of taking fence rails from Christopher Young's lot and admonished by the Court. At the same session he was fined for stealing wood from Thomas Edwards and for evil speeches to him, calling him "a base fellow, & yt one might Runn a half pike in his bellie & never touch his hart."