полная версия

полная версияCremation of the Dead

From these old-world practices – for they are old-world practices, although performed at the present day – we will now turn aside to examine into the modern and improved systems of cremation. The extracts which I shall make will be mostly from the work of Dr. De Pietra Santa.185 First of all come the experiments made by Dr. Polli at the gas works in Milan.

In a cylindrical retort of refracting clay, used for the distillation of coal-gas, was placed the body of an unfortunate poodle dog, drowned for contravention of the muzzle laws promulgated by the police. The dog weighed twenty-two and a half pounds. The apparatus was heated by a crown of flames issuing from a perforated circular tube. In order to render combustion as active as possible, the coal-gas was mixed with a certain quantity of pure air. Our readers will recollect this addition of atmospheric air is the principle of the Bunsen burner, which ensures perfect combustion of coal-gas, and produces a maximum of heat with a minimum of light. The cremation lasted several hours, producing a thick smoke, &c. After carbonisation, the skilful chemist succeeded in obtaining complete incineration, that is to say, the calcination of all the solid parts of the body, which weighed one pound fourteen-and-a-half ounces.

Satisfied with the result of this experiment, which proved the possibility of reducing the carcase of an animal to ashes by ordinary coal-gas, Dr. Polli proceeded with a second and more complete experiment. One improvement was the disposition of a vertical retort in such manner as to consume the gaseous products of combustion. This is easily effected by placing at the upper orifice of the retort a second ring of gas jets. On this occasion better arrangements were made for carrying out the principle of the Bunsen burner, with the result of producing the complete incineration of a dog weighing forty-two and three-quarter pounds in the space of a couple of hours. On this occasion the solid residue weighed only two pounds and some ounces.

Few have given more time and study to practical cremation than Professor Brunetti. This gentleman sent a case of apparatus to the Vienna Exhibition, and records his conviction – arrived at after five experiments upon human bodies – that the total incineration of a corpse and the complete calcination of the bones by fire is, under ordinary conditions, impossible. He has tried various combustibles, gas retorts, closed vessels, and the open air, and has arrived at the conclusion that special apparatus is indispensable to the success of any attempt at perfect cremation. His apparatus consists of an oblong furnace built of ordinary, or, still better, of refracting brick, and furnished with ten side openings, in order to give the power of regulating at will the draught, and consequently the intensity of the fire. In the upper part is a cornice of tiles, destined to support an iron framework, above which is the dome-shaped roof, furnished with cast-iron shutters, which may be opened or closed by means of regulators, to shut in the flame and concentrate the heat. The body to be incinerated is placed upon a thin metallic plate, suspended by stout iron wire. The operation may be divided into three sections. Firstly, the kindling of the body; secondly, its combustion; thirdly, the incineration of the soft parts, and the calcination of the bones. Wood having been piled up in the furnace and lighted, the body catches fire at the end of half an hour. A considerable quantity of gas is now evolved, and the moveable shutters come into operation. The body then burns freely, and, if the pile of wood have been deftly arranged, complete carbonisation ensues at the end of a couple of hours. The shutters are then opened, another sheet of metal is lowered over the carbonised mass to concentrate the heat still more, and the wood is renewed. By means of this apparatus, and at the cost of 160 or 180 lbs. of wood, complete cremation is achieved in two hours more. When the furnace is cold, the residue is collected and placed in a funereal urn. The last experiment of Dr. Brunetti was made upon the body of a man who died, at the age of fifty, of chronic bronchitis.

A description of a Siemens apparatus as constructed for use in Germany is given by Professor Reclam in an article entitled 'Die Feuerbestattung' in the 'Gartenlaube.' A sketch of it in action, partly copied from this article, is given in Plate I.

It consists of (1) a gasometer for the manufacture of the gas necessary to heat the furnace; (2) the furnace itself, with a regulator and a space for burning; (3) a chimney to take away the smoke &c. We may conceive a large, beautiful dead-house built for the purposes of cremation. In the midst, but invisible to those present, is a furnace. The funeral procession arrives at the house, and enters it the same as the churchyard is now entered. When the coffin has been placed on the tressel, and the usual ceremony ended, it is let down into the grave and disappears. In a short time after it is let down the covering of the furnace is removed, and replaced when it has received the coffin.

The process of cremation is effected by means of heated air. The gasometer is put in action by the consumption of coal, charcoal, peat, or wood. The gas thus produced is conducted through a pipe provided with a regulating-valve, where, meeting with a stream of air, also under regulation, it is converted into a flame. This flame extends through the room which has the regulator, so that the brick material which is piled up there is heated to white heat, and kept to this. The flame still continuing, supplies heat till the furnace or place for the reception of the body is heated to a weak red heat, when the flame escapes through a pipe into the chimney.

As soon as the furnace is in the condition thus described, the process of cremation goes on. The covering of the furnace is removed by the man who superintends the burning of the bodies. It is put back again, and the body subjected to the action of the red heat for a longer or a shorter time, according to its physical condition. After this is done the gas-valve is closed, and the air in consequence goes through the regulator into the place for burning. It is here heated in the regulator nearly to red heat, in which condition it comes to the bodies already, in some measure, dried, so that decomposition soon follows. The bones are decomposed by the action of the heat, while the carbonate dissolves, and the lime remains as dust. To collect this dust an instrument is provided, that it may be placed in a jar, or any other vessel, and preserved by the relatives of the deceased.186

The most perfect apparatus, however, yet devised for the reduction of a body to ashes is that adopted by Sir Henry Thompson. From his work upon cremation I take the following description, which will be always studied with interest. This extract will fitly conclude these quotations.

A powerful reverberating-furnace will reduce a body of more than average size and weight, leaving only a few white and fragile portions of earthy material, in less than one hour. I have myself personally superintended the burning of two entire bodies, one small and emaciated, of 47 lbs. weight, and one of 144 lbs. weight, not emaciated, and possess the products – in the former case weighing 1¾ lb.; in the latter, weighing about 4 lbs. The former was completed in twenty-five minutes, the latter in fifty. No trace of odour was perceived – indeed, such a thing is impossible – and not the slightest difficulty presented itself. The remains already described were not withdrawn till the process was complete; and nothing can be more pure, tested by sight or smell, than they are; and nothing less suggestive of decay or decomposition. It is a refined sublimate, and not a portion of refuse, which I have before me. The experiment took place in the presence of several persons. Among the witnesses of the second experiment was Dr. George Buchanan, the well-known medical officer of the Local Government Board, who can testify to the completeness of the process.

In the proceeding above described, the gases which leave the furnace-chimney during the first three or four minutes of combustion are noxious; after that they cease to be so, and no smoke would be seen. But these noxious gases are not to be permitted to escape by any chimney, and will pass through a flue into a second furnace, where they are entirely consumed; and the chimney of the latter is smokeless – no organic products whatever can issue by it. A complete combustion is thus attained. Not even a tall chimney is necessary, which might be pointed at as that which marked the site where cremation is performed. A small jet of steam, quickening the draught of a low chimney, is all that is requisite. If the process is required on a large scale, the second furnace could be utilised for cremation also, and its product passed through another, and so on without limit.

This plan, however, has been thrown into the shade by subsequent experiments: —

By means of one of the furnaces invented by Dr. Wm. Siemens, I have obtained even a more rapid and more complete combustion than before. The body employed was a severe test of its powers, for it weighed no less than 227 lbs., and was not emaciated. It was placed in a cylindrical vessel about 7 feet long, by 5 or 6 feet in diameter, the interior of which was already heated to about 2,000° Fahr. The inner surface of the cylinder is smooth, almost polished, and no solid matter but that of the body is introduced into it. The product, therefore, can be nothing more than the ashes of the body. No foreign dust can be introduced, no coal or other solid combustible being near it: nothing but heated hydrocarbon in a gaseous form, and heated air. Nothing is visible in the cylinder before using it – a pure, almost white, interior – the lining having acquired a temperature of white heat. In this case the gases, given off from the body so abundantly at first, passed through a highly-heated chamber, among thousands of interstices made by intersecting firebricks, laid throughout the entire chamber, lattice-fashion, in order to minutely divide and delay the current, and expose it to an immense area of heated surface. By this means they were rapidly oxidised, and not a particle of smoke issued by the chimney; no second furnace, therefore, is necessary by this method to consume any noxious matters, since none escape. The process was completed in fifty-five minutes; and the ashes, which weighed about 5 lbs., were removed with ease.

After such brilliant results – results at once expeditious, cleanly, and economical – well might Sir Henry Thompson challenge Mr. Holland187 'to produce so fair a result from all the costly and carefully managed cemeteries in the kingdom,' and safely might he even offer him twenty years 'in order to elaborate the process.'

An ordinary Siemens' regenerative furnace for cremation makes use of only hot blast, it being considered that the organic substance to be consumed would supply sufficient hydrogen and carbon, and that only hot air is required to produce excellent results. But a perfect apparatus would be constructed upon the principle exhibited in Plate II., which represents the cremation apparatus devised by Dr. C. W. Siemens, F.R.S., of Westminster.

The body to be reduced to its elements is placed in the chamber A (fig. 1), which is iron-cased and lined inside with a substance able to resist the highest temperature. Figs. 1 and 2 represent the consuming arrangement, which may form a portion of the chapel itself. Figs. 3 and 4 show the gas-producer, where the gaseous fuel is produced, and this may be situated at some distance from the building where the cremation is performed. These gas-producers are not only separate from the cinerator, where the heat is required, but may be multiplied or extended, so as to supply any number of cinerators, and so separately reduce a plurality of bodies. At the back of the heating chamber A are placed four firebrick-celled regenerative chambers for gas and air, seen in section at fig. 2, and these work in pairs. The gas carried from the gas-producer is directed into the gas regenerator, and the entering air into the air regenerator, and in these regenerators both gas and air are heated, attaining a temperature equal to a white heat before they reach the chamber A in which the body is laid. The heated air, after passing upwards through the regenerator, enters the consuming chamber at B, and the heated gas enters it at C. They thus enter the chamber separately, and with a sufficient velocity to impinge against the door of the chamber; but when they meet at the point D in the chamber, the gas and air mingle and add to the carried heat that due to the mutual chemical action. The result is a devouring flame. One pair of regenerators are always employed in conducting the heated air and gas into the chamber A, whilst the other pair are employed in carrying away the combined gases or expended fuel to the chimney. This expended fuel is nevertheless an immensely hot flame, and on its way to the chimney it proceeds downwards through one pair of the regenerators, the upper portion of which it heats intensely. Nearly the whole of the heat of the expended fuel is left in the regenerators, and the smokeless gases which enter the chimney to be cast into the air rarely exceed 300° Fahr. By means of valves the regenerators and air-ways which were carrying off the expended fuel, can be instantly used for carrying air and gas into the reducing chamber, and the heat left in them consequently utilised. Not only is a saving of 50 per cent. in fuel thus effected, but the noxious gases from the body would be entirely consumed in their passage down through the regenerators.

The gas-producer itself (figs. 3 and 4) works in the following manner: – The coal is supplied to the charging-box E every three hours or so, and slides down an inclined plane, the upper portion of which is solid and covered with firebricks. Upon this sloping bed the fuel is heated, and its volatile constituents are liberated, just as in a gas retort, leaving about 60 per cent. of carbonaceous matter, the complete combustion of which is brought about by the air which enters through the open part of the grate at the foot of the sloping bed. More carbonic acid gas is now evolved, and this non-combustible gas passes through the red-hot fuel, taking up in its passage another equivalent of carbon, and so becoming an inflammable gas, or what is called carbonic oxide. Should it be considered advisable to make use of steam, each cubic foot of which yields as much inflammable gas as five cubic feet of air, a pipe of water is allowed to run at the foot of the grate, and is there converted into steam by the radiant heat. The combustible gases now pass into the main gas flue, and inasmuch as this gas flue must contain an excess of pressure above the exterior air, so as to prevent the inroad of atmospheric air into the gas flue, and consequent partial combustion, the gas is allowed to rise – which it will do by its initial heat – some score of feet above the producers, and is carried horizontally through the wrought iron tube F into and then down into the furnace. The flat-lying tube being exposed to the air causes the gas in its passage through it to lose about 200° Fahr. of temperature, which increases its density, adds weight to the descending column of gas, and presses it on to the furnace. One estimable feature in this system of gas-producing is that the production can be arrested for half a day without deranging the producer, the fuel and brickwork being sufficiently bulky to maintain a dull red heat for that period. Air cannot enter the grate unless the gases given off in the producer are withdrawn to the furnace; and when the gas valve of the furnace is reopened, the production of the gases is once more continued.188

It has been urged against cremation by sentimentalists, that if the burning could be observed in even an improved apparatus, the process would prove a harrowing one, recall in fact to mind the horrors described by the Comte de Beauvoir in his Indian reminiscences.189 But no such thing would result, for whilst being consumed the body would remain of itself perfectly motionless and without visible contraction or convulsion. Several late human cremations which have taken place in the Siemens Works in Dresden, have been purposely witnessed by eminent scientific men and others, through the glass panel of the door which is always provided for the use of the manufacturing operator, and the utter absence of anything which could prove in the least distressing to the mind, the eye, or the imagination, is vouched for by all. The current of combined air and gas simply plays upon the body with a transparent flame, until the whole becomes incandescent. There is not even the least effluvium. In a late experiment, when nearly a quarter of a ton of animal matter underwent cinerary treatment at Dresden, the gases between the flue and the chimney proper were intercepted by an aspirator, and found perfectly inodorous.190 Once incandescent, the body soon assumes a hue of translucent white, and then speedily crumbles into ashes.

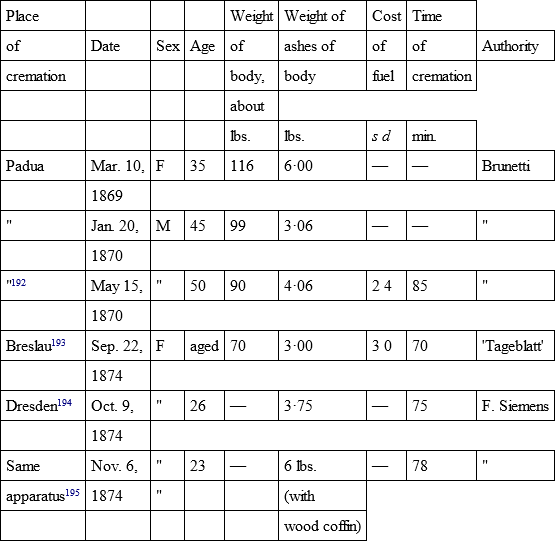

The quantity of ashes left from a body of average weight has been foretold by Sir Henry Thompson almost to the fraction of a pound. There is no doubt whatever also that the time named by him as sufficient for entire reduction will be borne out in practice. As regards the cost of cremation, Sir Henry is most assuredly correct in lauding its economy over interment. The cost of the fuel expended during the last three cremations in Germany did not exceed 3s., plus of course the percentage to be charged for attendance, and for the use of the apparatus, which latter would be trifling were it in constant use. When the clerical fees and all the costs of conveyance, &c., are added thereto, the whole sum would not necessarily exceed that of a seventh-class funeral in London.191

Примечание 1192

Примечание 2193

Примечание 3194

Примечание 4195

The above Table represents the details of six recent human cremations.196

The body to be burnt would, in the first instance, soon after death197 be placed, perhaps, in a coffin of some light material, and taken in due time to the mortuary,198 ready for conveyance to the 'cinerator.' And, as it is very desirable that the ashes of the body should be kept separate from those of any coffin, a shroud of some imperishable material will be carefully sought after by inventors. The ancient Greeks made use of sheets of asbestos, which is a fibrous form of hornblende;199 and those of the Egyptians who performed cremation enclosed the body in a receptacle of amianth, which is a similar incombustible mineral substance.200 Whether these materials will resist the intense heat of the Siemens apparatus remains to be seen; for I have had no opportunities of making experiments. Wood, at all events, is likely to be rejected, on account of the residue of carbon, &c. (charcoal), which might not be easily separated from the more precious relics. Lead would be equally objectionable, for, although easily fusible, it possesses certain disadvantages easily to be imagined. In all probability the most suitable material for the inner coffin, which alone is to be submitted to the impingement of the hot blast, will be zinc. This metal would entirely disappear in the fierce heat, the reason being that it is volatile, and would distil off – its boiling-point being 800 °Cent.,201 or 500° Fahr. below the minimum temperature which will reign in the chamber of the apparatus.

The English and the German machinery for the reduction of the body to ashes vary in a few particulars, but the general construction is the same, as will have been perceived. In one Dresden arrangement the body is lowered into a receiver below, and the idea of interment is thus in a manner preserved.202 In the English arrangement this is otherwise, and the coffin is made to gradually slide into the receiver, like a ship launched into water. The anguish induced by the moment of departure is in this way somewhat ameliorated, as there is no noise of lowering-machinery to grate upon the ear. At certain appointed words in our beautiful funeral service – for instance, 'ashes to ashes' – a curtain might be partially withdrawn, and the body, encased in a suitable shell, would gravitate slowly into the chamber of the apparatus, which would then immediately close noiselessly; to be opened only after the due reduction of the body. The utmost privacy would be insured, and no strange eyes could gaze upon it203 during the period of incineration. The funeral service could also be made to occupy the whole of the time necessary for sublimation if it were so desired, or a eulogy or other reference to the departed might form the subject of a discourse. The ashes could afterwards be collected, and reverentially placed in an urn,204 or other suitable receptacle, and conveyed to their last resting-place. Plate III. represents a view of a mortuary chapel, such as would probably be required in a Christian cemetery; and the scene there represented will serve to show how completely decorous the procedure would be.205 And one may here remark that the great advances made by science can nowhere better be evidenced than by a comparison between the modern and ancient systems of cremation. However well disguised in beautiful language – as, for instance, by Bulwer in the 'Last Days of Pompeii' – the barbarity of the method practised in classical times will be sensibly felt in the background.

It is likely enough that whenever cremation is again practised, urns will form the chosen receptacles of the ashes. Vases or urns have always been associated with sepulture in classical times. The finest vases which have come down to us from antiquity were not originally intended for sepultural purposes, but for the adornment of the mansion. Frequently, however, these were deposited in the tombs along with the unburnt body,206 as being the objects most valued by the deceased when living. The survivors doubtless held it as sacrilegious to make use of these favourite objects, for they are found unmolested even now.

It is worthy of remark that amongst the Ojibois Indians of the present day the canoe, gun, and blanket, which are laid upon the grave of each one of the tribe, although newly purchased, are never made use of again, nor ever stolen.207 Many other Indian tribes observe the same custom;208 and the Moldavians and the Caubees as well.209

The custom of depositing the painted vases in tombs ceased about the time when Italy and Sicily fell completely under Roman dominion. The Romans, who burnt their dead, deposited their ashes in urns, as we have seen. No ashes, it may be said generally, have been found in the Greek tombs of Italy, but the Romans made use of the vases found in tombs made by the Greeks there, as cinerary urns for their dead; and this appropriation was not uncommon. In the case of a member of the Roman family of Claudia an ancient Egyptian vase, now in the Louvre, was utilised in this manner.

The ancient painted vases are now divided into six classes, embracing forty-nine various shapes.210 The styles are also divided into Early or Egyptian, Archaic Greek, Severe or Transitional, Beautiful or Greek, Florid, and into those of the Decadence period. Should cremation be extensively adopted nowadays, it is not unlikely that all these forms and styles will be laid under contribution. A friend211 has kindly drawn for the present work a dozen urns, adapted for the reception of human ashes (see Plate IV.). Fig. 1 is Archaic in shape; fig. 3 belongs to the Perfect or Beautiful forms; and fig. 2 represents a shape often used during the Florid era. The others are original designs based upon classic lines, but not referable to any one period. Some very elegant forms of the ancient vases, copied from gems and other archæological resources, are to be found embodied in the monuments of the churchyards and cemeteries of the present day.212

Had the practice of cremation followed uninterruptedly down to our times, the receptacles for the ashes would doubtless have been shaped according to the prevailing taste of each period of architecture. For instance, the genius of the Semicircular style, which prevailed from the sixth to the twelfth centuries, and embraced the Anglo-Saxon and Norman periods, would have left its own peculiar mark, just as it has done upon the fonts which were sculptured during its sway. The Early Pointed, the Geometrical, and the Decorated and Late or Perpendicular Gothic periods would, in a similar manner, have influenced the symmetry of the vases produced between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries, and contributed their own quota of beautiful shapes. And, speaking generally, ecclesiastical taste, which presided over every detail of church construction down even to the piercing of the keys, would have been as easily recognisable in the vases which contained the ashes of the dead.