полная версия

полная версияThe Fleets Behind the Fleet

The look-out man under the conditions of the new warfare has need of his eyesight. Dangers overhead, dangers on the surface, dangers underfoot. To scan at one and the same moment the horizon for the conning tower of a U. Boat, the water around and ahead of him for mines and the sky for approaching aircraft is a task inconsistent with any form of contemplative philosophy. "When the ship was 22 miles S.S.E. from Flambro' Head," writes an officer, "the Second Mate reported he saw a mine. To pass a mine involves a penalty, so I turned back and got close to it. It had five prongs on it, and was right in the track of shipping. As I had no gun to destroy it, and in the vicinity of Flambro' would be the nearest patrol boat, I thought it best to put a mark on it, as we would possibly lose it through the night, and settle some one coming along. I ordered the small boat out although there was a moderate breeze S.W. with quite a choppy sea, also a N.E. swell. I could not ask any one to go and make a line fast to it, as it is a very dangerous object to handle, so I decided to go myself. When lowering the boat down, the Chief Officer and the Boatswain got into her, and wished to share the danger. I asked them to consider, and say their prayers. I also ordered the Second Mate that as soon as he saw we were connected with the mine to send the lifeboat to take us off the small boat, as we intended to leave her as a buoy or mark to the mine, and then we would advise another ship to send a patrol steamer. We got to the mine, but had great difficulty making a rope fast to it, owing to its peculiar shape. After two failures, we fell on a plan to make the rope stop from slipping under it. We put a timber-hitch round the body of the mine and hung the hitch up with strands to two of the horns. What with the bobbing up and down and keeping the boat from coming down on the horns, and cold water, it was no nice job. Anyhow it got finished at last, and it seemed so secure that I thought we would be able to tow it until we met a patrol boat, so when the lifeboat came I returned on board with her, and took her on board. She got damaged putting her out and taking in, owing to the ship rolling. I now picked up the small boat with the other two men and got another line connected on to the one on the mine and went slow ahead. This worked all right, but I thought she could go faster so put on full speed. This was now 6 p.m. About five minutes after full speed the mine exploded and sent the water and a column of black smoke from two to three hundred feet in the air. Several pieces of the mine fell on deck, small bits, also small stuff like clinker from the funnel. It was a relief to all hands, and possibly saved some other ship's mishap, as we met about twenty that night on the opposite course to us."

A chapter on "Pleasant Half hours with Aeroplanes" will form a part of future histories of the Merchant Service. Witness the experience of the Avocet on her voyage from Rotterdam. "The weather being calm and clear, sea smooth, but foul with drifting mines, three aeroplanes were observed coming up from the Belgian Coast, one being a large 'battle-plane.' In a few minutes they were circling over the ship, and the battle-plane dropped the first bomb, which hit the water 15 ft. away, making a terrific report, flames and water rising up for 50 ft., and afterwards leaving the surface of the sea black over a radius of 30 ft. as far as it was possible to judge. Altogether 36 bombs were dropped, all falling close, six of them missing the steamer by not more than 7 ft.

"After apparently exhausting all the bombs, the battle-plane took up a position off the port beam and opened fire at the bridge with a machine gun. The ship's sides, decks and water were struck with many bullets – it was like a shower of hail. A port in the chief engineer's room was pierced and his bed filled with broken glass.

"The battle-plane was handled with great skill, attacking from a height of from 800 to 1,000 feet. Going ahead of the ship, he turned and came end on to meet her, and when parallel to her dropped his bombs so as to have her full length and make sure of scoring a hit. The ship's helm was put hard-a-starboard, and as she swung to port three bombs missed the starboard bow and three the port quarter by at most 7 ft. Had the vessel kept her course these bombs would have landed on the forecastle head and poop deck.

"The two smaller planes crossed and recrossed the Avocet, dropping their bombs as they passed over her. They all made a most determined attempt to sink the ship which only failed because they hadn't nerve enough to fly lower.

"After the first bomb was dropped a rapid rifle fire was commenced which was kept up until the rifles were uncomfortably hot. The chief officer of the Avocet was lucky enough to explode a rocket distress signal within a few feet of one Taube; had it hit him there would have been a wreck in mid-air. The action lasted 35 minutes, and when it was over and the aeroplanes flew away the decks of the Avocet were littered with shrapnel… The look-out man on the forecastle head actually reported a floating mine right ahead of the ship while bombs were bursting all around. He stuck to his post through it all, and kept a good look-out."

It is the habit of nations to recall and glorify their past, to dwell with satisfaction upon the doings of their heroes, the achievements of their great men. These enter into and become a part of the national life. Perhaps the world may yet see another and a rarer thing – a nation weeping at the tomb of its honour. For with what emotion – will it be one of happiness? – can the Germany of to-morrow recall a history like the following?

French S. S. Venezia,Fabre, Line,At Sea, March 28th, 1917.The Managers, Messrs. The Union Castle Mail

S. S. Co. (Ltd.) London.

Gentlemen,

With deep regret I have to report the loss of your steamer Alnwick Castle, which was torpedoed without warning at 6.10 a.m. on Monday, March 19, in a position about 320 miles from the Scilly Islands.

At the time of the disaster there were on board, besides 100 members of my own crew and 14 passengers, the Captain and 24 of the crew of the collier transport Trevose whom I had rescued from their boats at 5.30 p.m. on the previous day, Sunday, March 18, their ship having been torpedoed at 11 a.m. that day, two Arab firemen being killed by the explosion, which wrecked the engine room.

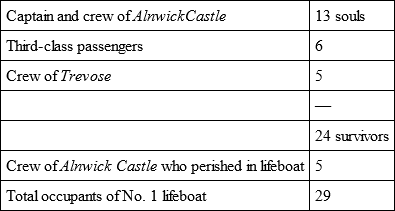

I attach a list of survivors from my lifeboat rescued by the S. S. Venezia on Friday, March 23, together with those who perished from exposure and thirst in the boat. It may be summarised as follows:

I was being served with morning coffee at about 6.10 a.m. when the explosion occurred, blowing up the hatches and beams from No. 2 and sending up a high column of water and débris which fell back on the bridge. The chief officer put the engines full astern, and I directed him to get the boats away. All our six boats were safely launched and left the ship, which was rapidly sinking by the head.

The forecastle was now (6.30 a.m.) just dripping, though the ship maintained an upright position without list. The people in my boat were clamouring for me to come, as they were alarmed by the danger of the ship plunging. The purser informed me that every one was out of the ship, and I then took Mr. Carnaby from his post, and we went down to No. 1 boat and pulled away. At a safe distance we waited to see the end of the Alnwick Castle. Then we observed the submarine quietly emerge from the sea end on to the ship with a gun trained on her. She showed no periscope – just a conning tower and a gun as she lay there – silent and sinister. In about 10 minutes the Alnwick Castle plunged bow first below the surface; her whistle gave one blast and the main topmast broke off, there was a smothered roar and a cloud of dirt, and we were left in our boats, 139 people, 300 miles from land. The submarine lay between the boats, but whether she spoke any of them I do not know. She proceeded north-east after a steamer which was homeward bound about four miles away, and soon after we saw a tall column of water, etc., and knew that she had found another victim.

I got in touch with all the boats, and from the number of their occupants I was satisfied that every one was safely in them. The one lady passenger and her baby three months old were with the stewardess in the chief officer's boat. I directed the third officer to transfer four of his men to the second officer's boat to equalise the number, and told them all to steer between east and east-north-east for the Channel. We all made sail before a light westerly wind, which freshened before sunset, when we reefed down. After dark I saw no more of the other boats. That was Monday, March 19.

I found only three men who could help me to steer, and one of these subsequently became delirious, leaving only three of us. At 2 a.m. Tuesday, the wind and sea had increased to a force when I deemed it unsafe to sail any longer; also it was working to the north-west and north-north-west. I furled the sail and streamed the sea-anchor, and we used the canvas boat-cover to afford us some shelter from the constant spray and bitter wind. At daylight we found our sea-anchor and the rudder had both gone. There was too much sea to sail; we manœuvred with oars, whilst I lashed two oars together and made another sea-anchor. We spent the whole of Tuesday fighting the sea, struggling with oars to assist the sea-anchor to head the boat up to the waves, constantly soaked with cold spray and pierced with the bitter wind, which was now from the north. I served out water twice daily, one dipper between two men, which made a portion about equal to one-third of a condensed-milk tin. We divided a tin of milk between four men once a day, and a tin of beef (6 lbs.) was more than sufficient to provide a portion for each person (29) once a day. At midnight Tuesday-Wednesday, the northerly wind fell light, and we made sail again, the wind gradually working to north-east and increasing after sunrise. All the morning and afternoon of Wednesday we kept under way until about 8 p.m., when I was compelled to heave to again. During this day the iron step of our mast gave way and our mast and sail went overboard, but we saved them, and were able to improvise a new step with the aid of an axe and piece of wood fitted to support the boat cover strongback. We were now feeling the pangs of thirst as well as the exhaustion of labour and exposure and want of sleep. Some pitiful appeals were made for water. I issued an extra ration to a few of the weaker ones only.

During the night of Wednesday-Thursday the wind dropped for a couple of hours and several showers of hail fell. The hailstones were eagerly scraped from our clothing and swallowed. I ordered the sail to be spread out in the hope of catching water from a rain shower, but we were disappointed in this, for the rain was too light. Several of the men were getting light-headed, and I found that they had been drinking salt-water in spite of my earnest and vehement order.

It was with great difficulty that any one could be prevailed on to bale out the water, which seemed to leak into the boat at an astonishing rate, perhaps due to some rivets having been started by the pounding she had received.

At 4 a.m. the wind came away again from north-east and we made sail, but unfortunately it freshened again and we were constantly soaked with spray and had to be always baling. Our water was now very low, and we decided to mix condensed milk with it. Most of the men were now helpless and several were raving in delirium. The foreman cattleman, W. Kitcher, died and was buried. Soon after dark the sea became confused and angry; I furled the tiny reef sail and put out the sea anchor. At 8 p.m. we were swamped by a breaking sea and I thought all was over. A moan of despair rose in the darkness, but I shouted to them, "Bale, Bale, Bale," and assured them that the boat could not sink. How they found the balers and bucket in the dark I don't know, but they managed to free the boat, whilst I shifted the sea anchor to the stern and made a tiny bit of sail and got her away before the wind. After that escape the wind died away about midnight, and then we spent a most distressing night. Several of the men collapsed and others temporarily lost their reason and one of these became pugnacious and climbed about the boat uttering complaints and threats.

The horror of that night, together with the physical suffering, are beyond my power of description. Before daylight, however, on March 23, the wind permitting, I managed with the help of the few who remained able, to set sail again, hoping now to be in the Bay of Biscay and to surely see some vessel to succour us. Never a sail or wisp of smoke had we seen. When daylight came the appeals for water were so angry and insistent that I deemed it best to make an issue at once. After that had gone round, amidst much cursing and snatching, we could see that only one more issue remained. One fireman, Thomas, was dead; another was nearly gone; my steward, Buckley, was almost gone; we tried to pour some milk and water down his throat, but he could not swallow. No one could now eat biscuits; it was impossible to swallow anything solid, our throats were afire, our lips furred, our limbs numbed, our hands were white and bloodless. During the forenoon, Friday 23rd, another fireman named Tribe, died, and my steward Buckley, died; also a cattleman, whose only name I could get as Peter, collapsed and died about noon.

To our unspeakable relief we were rescued about 1.30 p.m. on Friday, 23rd, by the French Steamer Venezia, of the Fabre Line, for New York for horses. A considerable swell was running, and in our enfeebled state we were unable to properly manœuvre our boat, but the French captain M. Paul Bonifacie handled his empty vessel with great skill and brought her alongside us, sending out a lifebuoy on a line for us to sieze. We were unable to climb the ladders, so they hoisted us one by one in ropes until the 24 live men were aboard. The four dead bodies were left in the boat, and she was fired at by the gunners of the Venezia in order to destroy her, but the shots did not take effect.

I earnestly hope that the other five boats have been picked up, for I fear that neither of the small accident boats had much chance of surviving the weather I experienced. At present I have not yet regained fully the use of my hands and feet, but hope to be fit again before my arrival in England, when I trust you will honour me with appointment to another ship.

I am, Gentlemen, your obedient servant,(Signed) Benj. Chave.Steamship Alnwick Castle torpedoed at 6.10 a.m. 19.3.17. Crew rescued by Steamship Venezia 23/3/17, and landed at New York: – B. Chave, master; H. Macdougall, chief engineer; R. G. D. Speedy, doctor; R. E. Jones, purser; N. E. Carnaby, Marconi operator; K. R. Hemmings, cadet; S. Merrels, quartermaster; T. Morris, A. B.; A. Meill, greaser; F. Softley, fireman; H. Weyers, assistant steward; S. Hopkins, fireman.

Deaths. R. Thomas, fireman; – Tribe, fireman and trimmer; – Buckley, captain's steward; W. Kitcher, foreman cattleman; Peter (?), cattleman.

Rescued passengers ex "Alnwick Castle" 3rd class. J. Wilson, J. Burley, G. Fraser, D. J. Williams, W. T. Newham, E. O. Morrison.

There are of course records which provide better reading. Worthy of the best sea company is the story of Robert Fergusson, a Glasgow man, but a naturalised American, and his companions Smith and Welch, who refused in the heaviest of gales to leave the tug Valiant, when she was abandoned by her Captain and crew in mid-Atlantic. "I wouldn't have brought her back for all the money in the world if the British Government hadn't wanted her," he said, "but I knew that every ship was wanted." Fortified by that thought Fergusson determined to stand by the vessel and save her if she could be saved. "Show your Yankee spirit," he cried to the Americans in the crew. And Welch responded, "I'm for you." "I'll not quit either," said Smith the fireman. And the great liner which had stood by and taken off the others left them – the three men – to fight their way homeward, if indeed that forlorn hope might succeed, in the battered craft, through the worst weather the Atlantic had known that winter. Smothered by great seas, with all the tug's gear on deck smashed or adrift, the three fought on, Fergusson on the bridge, Welch at the engines, and Smith toiling in the stokehold, each alone. Then the steering gear went, and the vessel was thrown on her beam ends. Wallowing in the trough, it seemed impossible that she could live, the seas mounting to her upper deck. But live she did, and without food or drink, with the last ounce of their strength spent and more than spent, supported by their own dauntless determination and that incalculable fortune which loves to side with a superb undertaking, they made land and the port of Cardiff, to the honour of both Britain and America, an alliance we may believe invincible.

To read too of men like the trawler skipper, who, when a shell from a pursuing submarine smashed part of the wheel under his hands, "went on steering with the broken spokes," fought his enemy with his light gun and finally drove him off, makes one feel that it is something to have entered life under British colours. Sir Percy Scott cannot have had the British sailor in his eye when in his forecast of the character maritime war would probably assume he wrote, "Trade is timid, it will not need more than one or two ships sent to the bottom to hold up the food supply of this country." How overwhelming is the evidence for this timidity. The timidity of Captain Lane for instance, who continued to fight the enemy submarine amid the flames which its shell fire had produced; beat off his pursuer, and when the crew were safely in the boats and the vessel in a sinking condition, with the assistance of the engineer himself beached his ship, and finally subduing the flames, repaired the damages and resumed his voyage. The timidity of the Parslows, father and son – the father, killed at the wheel, succeeded by the son, who resolutely held on his course and saved his vessel. The timidity of Captain Pillar, who saved seventy men of the Formidable by incomparable seamanship and a daring manœuvre in a furious gale, or of Captain Walker of the transport Mercian, an unarmed vessel, crowded with troops, who kept on his way, undeterred by the storm of shells from the enemy, though his decks were full of dead and wounded. The timidity aboard the Thordis, a heavily laden collier, attacked when head to wind and sea, an easy victim, capable of no more than 3 knots, whose Captain put over his helm, and crashing into the astonished enemy sent her to the bottom. There is the story of the timid skipper of the Wandle, another collier, who, blown off his feet on the bridge by the concussion of a shell, gave back shot for shot, sank his enemy, and in his little vessel, her flag still flying, made a triumphal progress up the Thames with her rent bulwarks as proof of her timidity; the sirens on the tugs ahead and astern advertising it; the bells ringing at Greenwich Hospital, and riverside London cheering itself hoarse for joy of it. There is the story of the timid Captain Kinneir, who, ordered to stop by a German cruiser, north of Magellan Straits, answered the order by driving his ship, the Ortega, right into Nelson's Straits, the most gloomy ocean defile in the world, without anchorage, an unchartered channel never before attempted, which no seaman knows or desires to know, and so baffled his pursuers who dared not follow. You cannot capture the record for it outruns description. These timid captains, in the spirit of the old English, fight till none is left to fight.

Then there are the timid apprentices and deckhands and engineers. The seas swarm with them, they are to be found on every cargo tank and collier and transport and ocean liner. You cannot rid yourself of these nervous sea-farers. There was Davies, second officer of the Armenian, who saved thirty-five of her crew; and Hetherington of the Jacona, who in somewhat similar circumstances swam from the sinking ship to a drifting boat, into which he dragged his shipmates clinging to drifting wreckage. There were the engineers of the Southport, at the Carolines, seized by the German corvette Geier. Left with her machinery dismantled that she might serve as an enemy store ship, these men in twelve days of feverish work replaced the essential parts, and setting sail made Brisbane, 2,000 miles away, in a ship capable only of steaming one way. There was the half hour's work of three men, Engineers Wilson, East and the mate Gooderham, of a fishing boat mined in the North Sea, the first of whom, heedless of the scalding steam in the damaged engine-room, rushed in and after desperate exertions plugged the hole caused by the explosion, while East dragged from an almost hopeless position in the bunker the imprisoned stoker, and Gooderham swung a boat over and rescued under the overhanging side of another trawler, mined at the same time, seven of her crew. Look through the long list of Admiralty rewards for timidity in rescue work, in battles against odds, in seamanship. Germany, hanging on the arm of the false jade to whom she has sold herself, the creed of frightfulness, was very sure.

"Swept clear of ships," was her description of the Channel. Pathetic delusion! Why it is more like a maritime fair. Never was there such a bustle of shipping since the world was made. An average of over a hundred merchant ships a day pass through the narrow gateway guarded by the Dover patrol. Motor boats, flocks of them; scores of traders at anchor in the Downs; busy transports on their way to Havre; up to windward a cluster of mine-sweepers; down to leeward a line of lean destroyers, it is night and day with them as with all the ships, through every changing mood of the Channel – rain, storm, snow blizzards, sunshine and sweet airs or "wind like a whetted knife." For this is the gate of all the gates, the vital trade route, and from Foreland to Start, from Start to Lizard in three years of war the German fleet has not seen these famous headlands! Very busy, but very much at home, are the British vessels in that long sea lane. Talkative too, for the gossip never ceases. Hoarse megaphone conversations, rocket and semaphore talk, wireless chatter without end. Within a few hours steaming of the lively scene, when you may count as many as fifty vessels within sight at one time, lies the magnificent German fleet, for it is magnificent, save the British the finest the world has ever seen, equipped with all the most destructive engines the heart of man could devise. Hindenburg and his devoted divisions suffer terrible things under the fire of 4,000 British guns, discharging 200,000 tons of shells within the passage of a few short weeks. Admirals Von Scheer and Von Hipper pace their quarter decks and take no notice. They know that these guns, these shells, and the troops behind them can enter France only by water.

Here surely was their opportunity, and yet only in the outer seas, and there only by furtive attacks, is the transport upon which all depends anywhere impeded. That the bridge from England to France stands firm, that the Channel is no sundering gulf, but as it were solid land, may seem to us as natural as it is essential, but that it does stand firm is not merely, if we ponder it, a wonder in itself, it is perhaps the greatest of the wonders that we have witnessed in these amazing years. By the navy that vital area, that great and indispensable bridge has been securely held, and when we say "the navy" let us now and always mean nothing short of British ships and sailors anywhere, everywhere, in all the range and variety of their sea-faring activities. Let us separate them neither in our thoughts nor our affections, and say of our merchant sailors and fishermen as of the Royal Navy that – what was expected of them they accomplished, what was required of them they gave; if courage it was there, if skill it was always forthcoming, if death they offered their lives freely. There were among them no strikers or conscientious objectors. In all the virtues that mankind have held honourable they need not fear comparison either with their own ancestors or with their adversaries. From "the stoker who put his soul into his shovel" to the Captain who was the last to leave his ship they upheld beyond reproach the chivalry of the great sea tradition. And if we say that the last chapter of the Merchant Sailor's history, tested by any standard you care to apply, is nobler than any previously written, we do him no more than justice, and yet ask for him universal and wondering admiration.