полная версия

полная версияIn to the Yukon

We reached Omaha, the chief city of Nebraska, late in the afternoon, coming into the fine granite station of the Burlington Railway system.

While in the city we were delightfully taken care of by our old school and college friends, to whom the vanished years were yet but a passing breath. We were sumptuously entertained at a banquet at the Omaha Club. We were dined and lunched and driven about with a warm-hearted hospitality which may only have its origin in a heart-to-heart friendship, which, beginning among young men at life’s threshold, comes down the procession of the years unchanged and as affectionately demonstrative as though we were all yet boys again. It carried me back to the days when we sat together and sang that famous German student song: “Denkt Oft Ihr Brueder an Unserer Juenglingsfreudigheit, es Kommt Nicht Wieder, Die Goldene Zeit.”

Omaha, a city of 100,000 inhabitants, forms, together with Kansas City on the south and St. Paul, and Minneapolis on the north, the middle of the three chief population centers between St. Louis, Chicago and Denver. It is the chief commercial center of Nebraska and of South Dakota, southern Montana and Idaho, and controls an immense trade.

In old times it was the chief town on the Missouri above St. Louis and still maintains the lead it then acquired. I was surprised to find it situated on a number of hills, some quite steep, others once steeper, now graded down to modern requirements. Its streets are wide and fairly well paved, and its blocks of buildings substantial. The residence streets we drove through contain many handsome houses, light yellow-buff brick being generally used, while Denver is a red brick town. The parks, enclosing hill and dale, are of considerable natural beauty, here again having advantage over Denver, where the flattened prairie roll presents few opportunities for landscape gardening.

The extensive stockyards and abattoirs of Armour, Swift and several other companies have made Omaha even a greater center of the meat trade than Kansas City. In company with W – I spent the morning in inspecting these extensive establishments. The volume of business here transacted reaches out into all the chief grazing lands of the far West. The stockyards are supposed to be run by companies independent of the packing-houses, and to be merely hotels where the cattle brought in may be lodged and boarded until sold, and the cattle brokers are presumed to be the agents of the cattle owners who have shipped the stock, and to procure for these owners the highest price possible. But, as a matter of fact, the packing-houses control the stockyards, dominate the brokers, who are constantly near to them and far from the cattle owners, and the man on the range who once ships his cattle over the railroads, forthwith places himself at the mercy of the packer – the stock having been shipped must be fed and cared for either on the cars or in the yards, and this takes money – so the quicker the sale of them is made the better for the owner. Hence, inasmuch as the packer may refuse to buy until the waiting stock shall eat their heads off – the owner, through the broker, is compelled to sell as soon as he can, and is compelled to accept whatsoever price the packer may choose to offer him. So the packing companies grow steadily richer and their business spreads and Omaha increases also.

The other chief industry of Omaha is the great smelter belonging to the trust. Incorporated originally by a group of enterprising Omaha men as a local enterprise, it was later sold out to the Gugenheim Trust, whose influence with the several railroads centering in Omaha has been sufficient to preserve the business there, though the smelter is really far away from ores and fluxes.

These two enterprises, the cattle killing and packing and ore-reducing, together with large railway shops, constitute the chief industrial interests of Omaha, and, for the rest, the city depends upon the extensive farming and grazing country lying for five hundred miles between her and the Rocky Mountains. As they prosper, so does Omaha; as they are depressed, so is she. And only one thing, one catastrophe does Omaha fear, far beyond words to tell – the fierce, hot winds that every few years come blowing across Nebraska from the furnace of the Rocky Mountains’ alkali deserts. They do not come often, but when they do, the land dies in a night. The green and fertile country shrivels and blackens before their breath, the cattle die, the fowls die, the things that creep and walk and fly die. The people – the people flee from the land or die upon it in pitiful collapse. Then it is that Omaha shrivels and withers too. Twice, twice within the memory of living man have come these devastating winds, and twice has Omaha suffered from their curse, and even now Omaha is but recovering her activity of the days before the plague, forgetful of a future that – well! men here say that such a universal catastrophe may never again occur.

And the handsome city is prosperous and full of buoyant life.

We now go on to St. Louis and thence to Cincinnati and so home.

TWENTIETH LETTER

ALONG IOWA AND INTO MISSOURI TO ST. LOUIS

Charleston, W. Va., October 23, 1903.Our journey from Omaha to St. Louis was down the valley of the Missouri, a night’s ride. We crossed the mighty river over an enormously high bridge and then followed the crest of an equally lofty embankment across several miles of wide, rich bottoms to Council Bluffs, in the State of Iowa. “Nobody dares fool with the Missouri,” a man said to me in Omaha, as he pointed out where the voracious river was boldly eating up a wide, black-soiled meadow in spite of the square rods of willow mats and tons of rocks that had been laid down to prevent it. “When the Missouri decides to swallow up a bottom, or a village, or a town, she just does it, there is no escape.” And even the citizens of Omaha do not sleep well of nights when the mighty brown tide fumes too angrily. Hence the extraordinarily high bridge and enormous embankment we traversed when we sought to cross over to dry land in Iowa. The waters of the Missouri are as swift as those of the Yukon, but the river flows for a thousand miles through the soft muds of the Western prairies, instead of through the banks of firm gravel, and it eats its way here and there when and where it chooses, and no man can prevent. Hence the railways, while they traverse the general course of the great valley of the Missouri, do not dare follow too closely the river banks, but they rather keep far away and have just as little to do with the treacherous stream as they may. So it was we did not see much more of the Missouri, but sped into wide, flat, rich stretches of alluvial country until darkness fell upon us and night shut out all suggestions of the river.When morning dawned we were among immense fields of tall corn, corn so high as to quite hide a horseman riding through it. The farm-houses were large and substantial. The farmstead buildings were big and trim. The cattle we saw were big, the hogs were big, the fowls were big. And over all there brooded a certain atmosphere of big contentedness. We were in the State of Missouri, and passing through some of its richest, most fruitful, fertile farming lands. A rich land of rich masters, once tilled by slave labor, a land still rich, still possessed by owners well-to-do and yielding yet greater crops under the stimulus of labor that is free.When we had retired for the night our car was but partially filled. When we awoke in the morning, and I entered the men’s toilet-room, I found it full of big, jovial, Roman priests. Our car was packed with them. They had got in at every station; they continued to get in until we reached St. Louis. The eminent Roman prelate, the Right Reverend Archbishop of St. Louis, Kain, once Bishop of Wheeling, had surrendered his great office to the Pope, and the churchly fathers of all the middle West were gathering to St. Louis, to participate in the funeral pageant. A couple of young priests were talking about the “old man,” while a white-haired father spoke of “His Eminence,” and I learned that Cardinal Gibbons, of Baltimore, was expected to also attend the funeral ceremonies.

When morning dawned we were among immense fields of tall corn, corn so high as to quite hide a horseman riding through it. The farm-houses were large and substantial. The farmstead buildings were big and trim. The cattle we saw were big, the hogs were big, the fowls were big. And over all there brooded a certain atmosphere of big contentedness. We were in the State of Missouri, and passing through some of its richest, most fruitful, fertile farming lands. A rich land of rich masters, once tilled by slave labor, a land still rich, still possessed by owners well-to-do and yielding yet greater crops under the stimulus of labor that is free.

When we had retired for the night our car was but partially filled. When we awoke in the morning, and I entered the men’s toilet-room, I found it full of big, jovial, Roman priests. Our car was packed with them. They had got in at every station; they continued to get in until we reached St. Louis. The eminent Roman prelate, the Right Reverend Archbishop of St. Louis, Kain, once Bishop of Wheeling, had surrendered his great office to the Pope, and the churchly fathers of all the middle West were gathering to St. Louis, to participate in the funeral pageant. A couple of young priests were talking about the “old man,” while a white-haired father spoke of “His Eminence,” and I learned that Cardinal Gibbons, of Baltimore, was expected to also attend the funeral ceremonies.

We breakfasted on the train, and in the dining-car sat at table with two brother Masons wearing badges, and from them I learned that they were also traveling to St. Louis, there to attend the great meeting of the Grand Lodge of the State of Missouri. The city would be full of Masons, and the ceremonies of the Masonic Order and of the Roman Church would absorb the attention of St. Louis for the next few days. And so we found it, when we at last came to a stop within the great Central Railway Station – next to that of Boston, the largest in the world – where we observed that the crowd within it was made up chiefly of men wearing the Masonic badges, their friends and families, and the round-collared priests. A strange commingling and only possible in America. In Mexico, a land where the Roman Church dominates, though it no longer rules, the Masons do not wear their badges or show outward token of their fraternal bonds. In England, where the king is head of the Masonic Order, there, until the last half century, the Roman Catholic subject might not vote nor hold office. Here in St. Louis, in free America, I saw the two mixing and mingling in friendly and neighborly comradeship.

I do not know whether you have ever been in St. Louis, but if you have, I am sure you have felt the subtle, attractive charm of it. It is an old city. It was founded by the French. The old French-descended families of to-day talk among themselves the language of La Belle France. For a century it has been the Mecca of the Southern pioneer, who found in it and about it the highest northern limit of his emigration. Missouri was a slave state. St. Louis was a Southern slave-served city. The Virginians, who crossed through Greenbrier and flat-boated down the Kanawha and Ohio, settled in it or went out further west from it. Alvah, Charles and Morris Hansford, the Lewises, the Ruffners, made their flatboats along the Kanawha and floated all the way to it. St. Louis early acquired the courtly manners of the South. She is a city to-day which has preserved among her people much of that Southern savor which marks a Southern gentleman wherever he may be. St. Louis is conservative; her French blood makes her so. She is gracious and well-mannered; her southern founders taught her to be so. And when the struggle of the Civil War was over, and the Union armies had kept her from the burning and pillaging and havoc and wreck that befell her more southern sisters, St. Louis naturally responded to the good fortune that had so safely guarded her, and took on the renewed energy and wealth-acquiring powers of the unfolding West. The marvelous developments of the Southwest, and now of Mexico, by American railroad extension, has built up and is building up St. Louis, just as the great Northwest has poured its vitalizing energies, its boundless wheat crops, into Chicago. Corn and cattle and cotton have made St. Louis, and Spanish is taught in her public schools. Chicago may be the chief of the cities upon the great lakes; St. Louis must forever remain the mistress of the commerce and trade and wealth of the great Mississippi basin, with New Orleans as her seaport upon the south, Baltimore, Newport News, Norfolk on the Chesapeake Bay, her ports upon the east. St. Louis is self-contained. She owns herself. Most of the real estate in and out of St. Louis is owned by her citizens. Her mortgages are held by her own banks and trust companies. Chicago is said to be chiefly owned by the financiers of Boston and New York. The St. Louisian, when he makes his pile and stacks his fortune, builds a home there and invests his hoard. The Chicagoan when he wins a million in the wheat pit or, like Yerkes, makes it out of street railway deals, hies himself to New York and forgets that he ever lived west of Buffalo.

Hence, you find a quite different spirit prevailing among the people of St. Louis from Chicago. This difference in mental attitude toward the city the stranger first entering St. Louis apprehends at once, and each time he returns to visit the great city, that impression deepens. I felt it when first I visited St. Louis just eleven years ago, when attending the first Nicaragua Canal Convention as a delegate from West Virginia. I have felt it more keenly on every occasion when I have returned.

The Great Union Depot of St. Louis is the pride of the city. It was designed after the model of the superb Central Bahnhof of Frankfort on the Main, in Germany, the largest in Europe, but is bigger and more conveniently arranged. In the German station, I noted a certain disorderliness. Travelers did not know just what trains to enter, and often had to climb down out of one car to climb up into another, and then try it again. Here, although a much greater number of trains come in and go out in the day, American method directs the traveler to the proper train almost as a matter of course.

From the station we took our way to the Southern Hotel, for so many years, and yet to-day, the chief hostelry in the city. A building of white marble, covering one entire block, with four entrances converging upon the office in the center. Here the Southern planters and Mississippi steamboat captains always tarry, here the corn and cattle kings of Kansas and the great Southwest congregate. The politicians of Missouri, too, have always made the Southern a sort of political exchange. Other and newer hotels, like the Planters, have been built in St. Louis, but none has ever outclassed the Southern. We were not expecting to tarry long at the hotel, nor did we, for after waiting only a short interval in the wide reception-room, a carriage drove up, a gracious-mannered woman in black descended, and we were soon in the keeping of one of the most delightful hostesses of old St. Louis. Her carriage was at our command, her time was ours, her home our own so long as we should remain. And we had never met her until the bowing hotel clerk brought her smiling to us. So much for acquaintance with mutual friends.

The morning was spent visiting the more notable of the great retail stores, viewing the miles of massive business blocks, watching the volume of heavy traffic upon the crowded streets. At noon we lunched with our hostess in a home filled with rare books and objects of art, collected during many years of foreign residence and travel, and I was taken to the famous St. Louis Club, shown over its imposing granite club-house, and put up there for a fortnight, should I stay so long.

In the afternoon we were driven through the sumptuous residence section of the city out toward the extensive park on whose western borders are now erected the aggregation of stupendous buildings of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. This residence section of St. Louis has always been impressive to me. There is so much of it. The mansions are so diverse in architecture, so splendid in design. “Palaces,” they would be called in England, in Germany, in France. Here the plain St. Louisian says “Come up to my house,” and walks you into the palace with no ado. Evidences of the material wealth of this great city they are. Not one, not two, but tens and hundreds of palatial homes. Men and women live in them whom you and I have never read about, have never heard about, will never know about, yet there they are, successful, intelligent, influential in the affairs of this Republic quite as much so as you and I. And the larger part of these splendid mansions are lived in by men and women who represent in themselves that distinctively American quality of “getting on.” One granite palace pointed out to me, is inhabited by a man and his wife, neither of whom can more than read and write. Yet both are gifted with great good sense, and he lives there because he saved his wages when a chore hand in a brewery until at last he owned the brewery. Another beautiful home is possessed by a man who began as a day laborer and then struck it rich digging gold in the Black Hills. Calves and cattle built one French chateau; corn, plain corn, built several more, and cotton and mules a number of others. Steamboats and railways, and trade and commerce and manufactures have built miles of others, while the great Shaw’s Botanical Garden, established and endowed and donated to the city, came from a miserly bachelor banker’s penchant to stint and save. The incomes of the hustling citizens of St. Louis remain her own; the incomes of the rent-payers of Chicago, like the interest on her mortgages, go into the pockets of stranger owners who dwell in distant cities in the East.

The extensive Fair grounds and Exposition Buildings were driven upon and among. A gigantic enterprise, an ambitious enterprise. St. Louis means to outdo Chicago, and this time Chicago will surely be outdone. The buildings are bigger and there are more of them than at Chicago. They are painted according to a comprehensive color scheme, not left a blinding white, less gaudy than the French effort of 1900, more harmonious than the Pan-American effects at Buffalo two years ago. The prevailing tints are cream white for the perpendicular walls and statuary, soft blues, greens, reds, for the roofs and pinnacles, and much gilding. More than twenty millions of dollars are now being expended upon this great Exposition show. For one brief summer it is to dazzle the world, forever it is to glorify St. Louis. The complacent St. Louisian now draws a long breath and mutters contentedly, “Thank God, for one time Chicago isn’t in it.” The Art buildings alone are to be permanent. They are not yet complete. I wonder whether it will be possible to have them as splendidly sumptuous as were the marble Art Palaces I beheld in Paris three years ago – the only works of French genius I saw in that Exposition that seemed to me worthy of the greatness of France. The Exposition grounds and buildings are yet in an inchoate condition, and but for the fact that Americans are doing and pushing the work, one would deem it impossible for the undertaking to be completed within the limited time. As it is, many a West Virginian and Kanawhan will next summer enjoy to the full these evidences of American power.

In the late afternoon we were entertained at the Country Club, a delightful bit of field and meadow and woodland, a few miles beyond the city. Here the tired business man may come from the desk and shop and warehouse and office, and play like a boy in the sunshine and among green, living things. Here the young folk of the big city, some of them, gather for evening dance and quiet suppers when the summer heat makes city life too hard. Here golf and polo are played all through the milder seasons of the year. We were asked to remain over for the following day, when a polo match would be played. We should have liked to see the ponies chase the ball, but our time of holiday was coming to an end. We might not stay.

In the evening we were entertained at a most delightful banquet. A large table of interesting and cultivated people were gathered to meet ourselves. We had never met them before, we might never meet them again, but for the brief hour we were as though intimates of many years.

All the night we came speeding across the rolling prairie lands of Illinois and Indiana into Ohio. A country I have seen before, a landscape wide and undulating, filled with immense wheat and corn fields. The home of a well-established and affluent population. The sons and grandsons of the pioneers who, in the early days of the last century, poured in from all quarters of the East, many Virginians and Kanawhans among the number. A country from which the present younger generations have gone and are now going forth into the land yet further west, and even up into the as yet untenanted prairies and plains of the Canadian north.

In the morning we were in Cincinnati and felt almost at home. The city, smoky as usual, marred by the blast of the great fire of the early summer. The throngs upon the streets were just about as numerous, just about as hustling as those elsewhere we have seen, yet there was a variation. The men not so tall, more chunky in build, bigger round the girth, stolid, solid. The large infusion of German blood shows itself in Cincinnati, even more than in St. Louis, where the lank Westerner is more in evidence.

It was dusk when the glimmering lights of Charleston showed across the placid Kanawha. We were once more at home. We had been absent some seventy days; we had journeyed some eight thousand miles upon sea and lake and land. We had enjoyed perfect health. We had met no mishap. We had traveled from almost the Arctic Circle to the sight of Mexico. We had traversed the entire Pacific coast of the continent from Skagway to Los Angeles. We had twice crossed the continent. We had beheld the greatness of our country, the vigor and wealth and energy of many cities, the splendor and power of the Republic.

Notes

[A]Caribou Crossing now called Carcross.

Transcriber’s Note

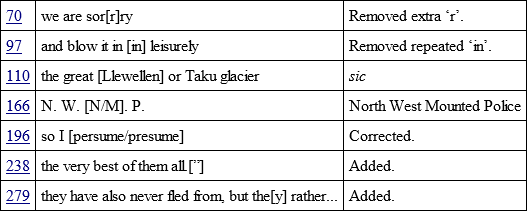

Small inconsistencies in punctuation in the Index and captions of photographs have been resolved. Two ‘N’ entries in the Index (“Narrow-gauge railway” and “Northwest Mounted Police”), were misplaced, and have been moved to their correct positions.

There were several other indexing errors:

“Portland was corrected to refer to p. 219.

“Cincinati” was corrected to refer to p. 324.

The following obvious printer’s errors are noted, and where unambiguous, have been corrected.

End of Project Gutenberg's In to the Yukon, by William Seymour Edwards

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IN TO THE YUKON ***

***** This file should be named 42611-h.htm or 42611-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/4/2/6/1/42611/

Produced by KD Weeks, Greg Bergquist and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Updated editions will replace the previous one-the old editions will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given away-you may do practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is subject to the trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.