полная версия

полная версияThrough Scandinavia to Moscow

We were in Russia. We had run the gauntlet of the border, – our passports had been sufficient, and we were at last safely within the dominions of the Czar. Would it be as difficult to get out?

XVII

St. Petersburg – The Great Wealth of the Few – The Bitter Poverty of the Many – Conditions Similar to Those Preceding the French Revolution. 2

Grand Hotel de l’Europe,St. Petersburg, Russia,September 18 (N. S.), 1902.So much has been jammed into the last two days that my pen is like to burst. Splendor and squalor, the glitter of twentieth century civilization, the sombre shadow of barbarism, are here entwined in inextricable comminglement. The city is filled with stately buildings of gigantic and imposing dimensions; with wide, straight boulevards and streets. The sidewalks and droschkies are gay with the dashing and gaudy uniforms of innumerable soldiery, and the fine dresses of elegant women. Yet many of these great buildings are in ill repair, and what you at first imagine to be magnificent stone, reveals itself to be a stucco of rotting wood and crumbling plaster; the broad thoroughfares are abominably paved, and pitifully cared for by abject wretches wielding dilapidated birch-stick brooms.

The superb horses – stallions, all of them – whirl past, driven by izvostchiks in dirty, truncated plug-hats and blue dressing-gown-like kaftans, whose sodden faces tell of vodka and hopeless haplessness. Beggars swarm (frightful creatures), and the faces of the officers, fine big men in striking uniforms, are dissipated, hard and cruel.

We are in a huge hotel. Big men in uniform open the door; big men in livery fill the halls; the rooms are big, ours is immense, with double windows, It is steam-heated, and also has hearth fires of burning wood. The building is warmed all through, even the halls. There are French waiters in the big dining-rooms; there is delicious food and delightful coffee, whose aroma is very perfume of the Orient; the beefsteaks are juicy, thick and tender. We have had no such meals since leaving America. On each story there is an elaborate bar for serving vodka (a fierce white whisky distilled from wheat) and drinks to the guests of that particular floor, and a single bath room, and a single diminutive toilet for both sexes’ common use.

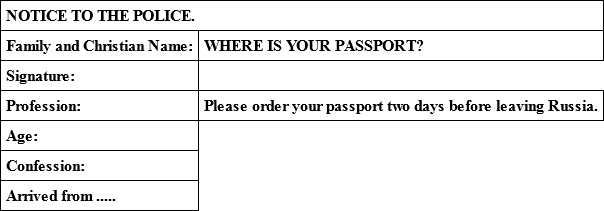

The moment we set foot within the doorway of the hotel, up stepped an official, in blue and gold, and demanded our passports, and we were requested also to sign a paper like the one enclosed, viz.:

This to be at once filed with the police department, and the passport not to be given back until we should notify the same big official, – whose duty it was to stay right there and watch all guests of that hotel, and who must be notified twenty-four hours before we leave the city, – when he will return the passport two hours before the said time set, and give it to me only upon my paying him the government fee of ten rubles (five dollars) in good yellow gold.3 And right outside the door of our apartments, seated at a little table, are two officials, pen and paper in hand, who set down the hour and the minute of the day we enter and come out. They were there when we went to breakfast; they, or others as fox-jowled and lynx-eyed, were also there when we returned from the theater late at night, and they are there all through the day. Our Swedish guide, who does the duties of courier and shows us about the great city, is also registered at the police department, and he has to hand in every night a written report of what he has done with us all through the day, where we have gone, what we have seen, and we suspect even what we may have said. On the streets, big sword-begirded policemen stand at the intersections of the ways, pull out a little book from their pockets and make note of our passing that particular spot at that certain hour; at night these reports also are handed in to the central police office to be checked up against the statements of the guide and the spies at the hotel.

We are in the capital city of the mighty Russian Empire; in the capital created by Peter the Great amidst and upon the marshy delta of the river Neva; a city of more than a million inhabitants; a city spread out over vast distances; a city whose disproportionately wide streets and boulevards are paved with wood, wood that is rotting all the while, leaving big holes into which a horse, a team, may plunge and disappear, because only wood will float upon the marshy mire of the mucky islets, and stone and brick will eventually sink from sight; a city whose top-heavy palaces and public edifices are so treacherously set upon the sands that they must constantly undergo costly repairs; a city builded upon foundations so unstable that the springtime floods of the river Neva ever threaten permanently to wipe out its very existence; a city where the palaces of the always widening circle of the Imperial princes of the blood, and of the upper nobility, and of the great bureaucratic chiefs, are builded with an arrogance of dimension, an elaborateness of design, a lavishness of cost that beats anything an American billionaire has ever tried to do, or dreamed of doing in San Francisco or New York; and yet a city abounding in the mean, small, log and wooden cabins of the very poor; a city where penury and poverty and dire pinch protrude their squalid presence in continual tragic protest against the flaunted and wanton riot of unmeasured wealth, possessed by the very few.

This morning as I walked upon the Nevsky Prospekt, the Broadway of the Imperial capital, and watched the movement of mankind along the way, and beheld the extraordinary contrasts between those who walked and those who rode; as I saw the burly policeman arrest the shabby foot-farer for nearly being run down, while he let the haughty grandee drive freely on; as I beheld poverty and wealth in such flagrant contrast, and realized that a standing army is kept ever armed and girt to protect and uphold the privilege and security of the rich; as I beheld the surly, sour, sombre faces of those who wore no gaudy covering of broadcloth and gold lace, my fancy harked back to the time, somewhat more than a century ago, when the King and Nobles of France drove through the Rues of Paris in all their glittering splendor, trampling down in their pride of power the pedestrian who failed to escape from their sudden approach. How secure they felt in their arrogant enjoyment of prerogative and rank! How contemptuously they disdained the humble claims of the glitter-proletarian, of the peasant on the land! Louis XIV had cried “L’etat c’est moi.” Was that not enough! And yet, I had stood in the Place de la Concorde, almost on the very spot where, inspired by the hatred of the Sansculottes, Mademoiselle La Guillotine had bit off the dull head of Louis XVI, and cut through the fair throat of Marie Antoinette.

It may be possible for Russia and her governing men, her Bureaucratic Autocracy, yet a little while to postpone the fateful hour. By means of foreign wars it may be possible to play the old game of diverting the public mind from its own bitter ills; by promises of fair and liberal dealing it may be possible to calm the public mind – cajole it until the promises are duly broken, as is invariably the case. Whatever fair-speaking and fat-feeding officialdom may to the contrary assert, the impression I gain amidst all this splendor and pomp and glare of supreme, concentered power of the few is that, beneath this opulent exterior, deep down in the hearts and even below the conscious working of their minds, there to-day abides among the masses of the Russian people – who after all hold in their hands the final power – a profound and monstrous discontent: a discontent so deep-rooted and so intense that when the inevitable hour strikes, as strike it must, the world will then behold in Russia a saturnalia of blood and tears, a squaring of ten centuries’ accounts, more fraught with human anguish and human joy than ever dreamed a Marat and a Robespierre, more direful and more glad than yet mankind have known.

We drove about the city like grandees. Our landau was just such as Russian nobles like best to use; our splendid pair of sorrel stallions pranced upon their heels and neighed and ran just as all nobles’ horses should; and our well-distended driver, of enormous and deftly-padded girth, sat belted with a big embroidered band, and guided the horses he never dreamed to hold, and helloed loudly to those who did not fly out of the way, just as would any driver of the Blood! We almost ran over some slow-moving man or woman, foot-weary wretch, at every crossing of a street!

Many palaces and public buildings we visited – enormous edifices, all of them, with innumerable and extensive halls and immense chambers finished in gold and alabaster and gaudy hues, with countless servants and lackeys in livery and lace, gold lace, to care for them, and watch over them, and fatten upon a government graft or easy-gotten fee. Suites of enormous apartments they were, which are never used and never are likely to be used.

The paintings of the great masters collected in the galleries of the Hermitage and Winter Palaces, accumulated by the Czars, are among the most renowned in Europe. The reception halls and audience chambers and ballrooms and dining halls of these palaces are designed and intended to dazzle and impress whosoever are given the chance of beholding them. At the same time, the library and study of the late Czar, Alexander III, is a small and plainly furnished room, with the atmosphere and markings of a man of simple tastes, who laboriously worked, worked as no other official of the Bureaucracy in Russia pretends to work.

We traversed the suites of apartments used by the Imperial family, when sojourning in St. Petersburg during those portions of the winter season when the court there gathers, and we noted the outer guardrooms where night and day stand the faithful watchers with sleepless vigil, and we realized, perhaps for the first time, that this man, so steeped in power, is after all but a prisoner of the system which locks him in and binds him fast and robs him of that independence of action which you and I enjoy. He is become but a creature of the great machine that governs, a slave of the system which Peter the Great set up for the furtherance of his Imperial will, a system of government which has so developed and spread out that to-day the Czar of all the Russias is merely the puppet of its will, the tool of the greedy, grasping, intriguing, governing Bureaucracy.

On approaching the city, our straining eyes first caught sight of the gilded, glittering domes and spires of the great cathedrals and churches with which it is so abundantly supplied. The domes of St. Isaac, of our Lady of Kazan, of Alexander Nevsky, and the spires of St. Peter and St. Paul, each and all told us that whatever else we might discover, we were yet entering a city and a land where the people counted not the cost of the splendid housing of their faith. And so we have found it. The wealth of gold and of silver, of precious stones and of priceless stuffs with which these churches are adorned and crammed, excels anything of which the western brain has ever dreamed. Each great church is famed and honored for its particular beneficence, its peculiar holiness, and to each one comes in procession perpetual an innumerable throng to pray and worship and to receive the blessings flowing from that especial fane. Even in the ancient log cabin, said to be the actual house erected by Peter himself, is established a shrine, where priests continuously intone the beautiful service of the Russian church and where thousands of devoted worshipers swarm in and out all the day long, and the night as well, praying to Imperial Peter’s now sainted ghost.

In the noble chamber of the golden-spired cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul lie the white marble tombs of the Romanoffs, where is also kept up throughout the day and night yet another sumptuous service for the repose of the souls of the illustrious dead. In the great monastery of Alexander Nevsky is each day maintained a simple and splendid choral service which multitudes attend, and where the melancholy Gregorian chanting and intoning of the black-robed long-bearded monks reveal new organ stops in the human voice.

Naturally, an American has great sympathy for the Russian people who have so little, while he has so much. In America we send our girls and boys to school as a matter of course. Here in the ornate center of autocracy, I have seen no building that I recognized as a common school, nor in Russia is there such a system, as we know it.

To the western mind three things stand out above all else in Russia:

(1) The concentrated wealth and privilege of the few – the big grafters who have seized it all.

(2) The opulence and extraordinary power of that ecclesiastical organization, the “Holy Orthodox Church” itself an engine of the autocratic rule, – used to cover atrocious authority with gilded cassock and priestly cope.

(3) The profound poverty and hopeless subserviency of the Russian people – those who are robbed and ruined by the grafters and hoodooed by the Church.

XVIII

En Route to Moscow – Under Military Guard – Suspected of Designs on Life of the Czar

Moscow, Russia, September 19, 1902, 10 P. M.We took the Imperial Mail train as determined. Foreign travelers generally journey by the night express, which arrives at Moscow only an hour behind the Imperial Mail, but it leaves St. Petersburg at so late an hour that there is little chance to see the country traversed. We made up our minds to take the more democratic train, which goes in the middle afternoon and stops at all way-stations. This would give us an opportunity to see more of the people as well as a longer season of daylight to watch the passing panorama of the land. We knew no reason why we should not take the train of our choice. It was true that our guide urged us to go by the night express. It was also true, when I presented my passport to the ticket agent at the railway station, the day before, and requested tickets, that he advised us to make the journey by the night express, nor would he at first agree to sell us tickets by the Imperial Mail, but told us to come back again two hours later, when he would let us know whether there were any berths unsold in the train’s through sleeper. It was also true that when we returned, he again advised us to take the night express. But our minds were made up, and we at last secured the tickets we wanted, and became entitled to an entire stateroom upon a designated car.

When we left the Hotel de l’Europe, the government official to whom I had returned my passport, after having bought my tickets, emerged from his office, received graciously his ten rubles, and again handed me the document; the sundry flunkies in liveries and spies in uniforms obsequiously bowed us out of the establishment, and our very competent guide immediately packed us into several droschkies and galloped us along the Nevsky Prospekt to the huge government station of the railway running to Moscow. The instant our izvostchiks brought their horses to a stop, we were surrounded by a swarm of porters clad in white tunic aprons and flat caps, who seized our bags, and preceded us through the large waiting room to the gates admitting to the train platform. Here our tickets were scrutinized, and a group of uniformed officials, who seemed to be awaiting us, informed us that the car in which our stateroom had been sold being already filled, another stateroom in another car was placed at our disposal. They then led the way to the front of the long train, and showed us into a large combined sleeper-and-chair car immediately back of the engine. Several soldiers were standing guard near by. We were evidently expected and were especially provided for. We almost had the car to ourselves. The only other passengers were a Russian officer and his orderly. We were at the head of a train made up mostly of mail cars locked and sealed, having at the rear several passenger coaches. But we were separated from all these latter, and we seemed to be objects of unusual interest. Many strange faces flattened against our windows, peering in at us, and the orderly locked up with us never took his eyes away from us. This did not annoy me, however, for I presumed he was admiring the beauty of our American women.

The train was a long one, – and such huge cars. The Russian gauge is five feet, the cars are long, and half as big and wide again as are the American cars, and are heated by steam, having double windows prepared against the cold. We had secured a whole compartment in which the two seats, facing each other, pull out and the backs lift up, making four berths, two lower, two upper, placed cross-wise. You pay one ruble (fifty cents) for blankets, sheets and towels. We put H and Mrs. C in the lower berths. Mr. C and I took the uppers. The car had only two more staterooms, one on each side of our own, and then a large drawing-room with reclining chairs. The stateroom ahead of us was occupied by the officer; his orderly slept on a chair in the salon. In the stateroom behind us were two railway guards. After we entered the car, the door was closed and locked by an official who stood on the outside. The officer and his orderly were locked in with us. Our trunk was checked through to Moscow by the guide, very much as we would have done it at home. He gave me the check, and I paid him his last pourboire before we entered. This was the only daily local train going southeastward, and whoever would leave St. Petersburg for the way stations must travel by it.

Our first impression, after leaving the city, was that of the flatness and the vacantness of the land; the landscape was marked here and there with insignificant timber, birches, firs and wide reaches of tangled grasses, and seemed uninhabited. There were no sheep, no hogs, no goats. Occasionally we saw herds of cattle and some horses, but very little tillage anywhere. The few houses, mostly low built, were of small-sized logs, or slabs. Towns and villages were few and far apart. In the towns were rambling wooden buildings, all just alike; in the villages were log and wooden cabins, scattered along a single wide street, and these streets were deep mud and mire from door to door. Here and there was a wooden church painted green, with onion-shaped steeple gilded or painted white, but there were no schoolhouses anywhere. At all the railroad stations were many soldiers, and dull-looking, shock-headed peasants, men clad in sheepskin overcoats with the wool inside, and women in short skirts wearing men’s boots, or with their legs wrapped in dirty cotton cloth tied on with strings, their feet bound up in twisted straw. It was a desolate, monotonous, dreary, sombre land. We saw no smiling faces anywhere, but always were the corners of the mouth drawn down. Now and then we passed a large town, with a commodious, well-built station of brick and stone. Here and there we saw huge factories and mills, all belonging to the government of the Czar.

We stopped at Lubin for supper. The guard unlocked our car, opened the door and pointed to the station, where we found a monster eatingroom with huge lunch counters on either side and long rows of tables down the middle. Everybody was standing up; there were no seats anywhere. Hot soft drinks were served at the side counters and smoking coffee and tall glasses of hot, clear tea. The Russian swallows only hot drinks and eats only hot foods. On the center tables, set above spirit lamps, were hot dishes with big metal covers. There were glasses of hot drink for a few kopeeks, which the Russian pours down all at once. Taking a plate from a pile standing ready, you help yourself to what victuals you choose. There were hot doughnuts with hashed meat inside, hot apple dumplings, hot juicy steaks, hot stews, hot fish; all H-O-T. When you have eaten your fill, you pay your bill at a counter near the entrance, according to your own reckoning. The Russian is honest in little things, and nobody doubts your word or questions the correctness of your payment. The eatingroom was full of big, tall, robust, fair-haired, blue-eyed men and a few women. The Russian is big himself, he likes big things, he thinks on big lines, he sees with wide vision, too wide almost to be practical. Hanging around the station were groups of unkempt, dirty peasants. We see such groups of gaping peasants at every station, always a hopeless look of “don’t care” in their eyes.

The train ran smoothly and we slept well. All Russian cars are set on trucks, American fashion, and there is no jarring and bouncing as in England’s truckless carriages. We traveled over an almost straight roadway, traversing the Valdai hills, the brooks and rivulets of which, uniting, give rise to the mighty Volga, and crossing the river passed through the city of Tver during the night. It was just daylight when I awoke. I at once arose, and then waked Mr. C and afterward we aroused the ladies. A different military officer and a different orderly were now traveling in our car. The officer seemed to have kept vigil in the compartment ahead of our own. When I came out of the stateroom, he was standing smoking a cigarette in the aisle just outside our door. When I went to the toilet-room he followed me and then returned to the door of our stateroom. He watched us all, even standing guard at the door of the toilet-room when occupied by the ladies. We were evidently in his charge. Later, I made acquaintance with him, accosting him in German, to which he readily replied. He was a medium-sized, wiry man with dark hair and eyes, close-cropped beard and long moustaches. He was a “lieutenant-colonel of infantry,” he said.

The night before, as we rode along, we noticed many soldiers gathered everywhere at the stations. Now there were none, but instead there was a soldier pacing up and down each side of the track, a soldier every sixteen seconds! His gun was on his shoulder. He wore a long brown overcoat reaching to his heels, and a vizored brown cap. At all the bridges there were several soldiers, at each culvert two. After a few miles of soldiers, I commented on this, to me, extraordinary spectacle, and asked the colonel what it meant. “Do you not know,” he said, “the Czar is coming in half an hour? He is returning from the autumn manoeuvers in the south!” Presently, we drew in on a siding. I wanted to go out with my kodak and take a snapshot. He said, “Es ist verboten (It is forbidden). You cannot go out.” He then asked to see my kodak, which he examined with the greatest care, taking it quite apart. He then handed it back to me saying, apologetically, “Bombs have been carried in kodak cases, you know.” Soon we heard the roar of an approaching train. The ladies pressed to the windows. The uniformed attendant stepped up and pulled down the shades right in their faces. I demurred to this and appealed to the colonel, who then directed the guard to raise the curtains, seeming to censure him in Russian. The ladies might look. A train of dark purple cars richly gilded flashed by. Was it the Czar? No! Only the Court. Another train just like the first would follow in half an hour and the Czar would be on that. But none of the public might know on which train he would ride. The colonel turned to me and said, “You kill Presidents in America. We would protect our Czars here! We also have Anarchists.”

I could not forbear remarking upon the excessive number of men in uniforms, soldiers apparently, I met everywhere in Russia, as well as the great expanse of vacant land, saying to him, “You have too many soldiers in Russia. You should have fewer men in the army and more men out on the land tilling the soil and supporting themselves. It is unfair to those who work to be compelled to feed so many idle mouths.” He answered me frankly. He said, “It is necessary to have these soldiers. The peasants are ignorant. We take their young men and make soldiers and good citizens out of them. The army is a school of instruction; it is there the peasant learns to be loyal and to shoot.” And then he said with emphasis, “Ah! In America you don’t need to learn to shoot, you are like the Boers, you all know how to shoot,” which view of American dexterity, I, of course, readily acceded to. And when I asked him why it was there were no schools or schoolhouses in all this journey, he replied that it was useless to build schools for the peasant, for he did not wish to learn. He had no desire to improve. “You in America,” he said, “are every year receiving the energetic young men of all Europe. You are constantly recruiting with the vigor and energy of the world. You can afford to have schools. Your people want schools, but the Russian people want no schools. They will not learn, they will not change, and no young men ever come to Russia. We receive no help from the outside. Nobody comes here. Nobody. Nobody (Niemand, Niemand). We have always the peasant, always the peasant (Immer der Bauer).” And then he asked me about President Roosevelt, and inquired whether he would succeed himself for a second term, remarking that “Mr. Roosevelt was greatly admired by the Russian army.” “The Russian army sees in your President Roosevelt a great man,” he said, then added, “in France the Jews and financiers set up a President, but in America you choose a man who is a man.” We became very good friends, and he accepted from me an American cigar, one of a few I had brought along and saved for an emergency. At subsequent stations he allowed me to get out in his company, and even let me take his picture along with some of the other officers who stood about. The Czar had passed. The weight of responsibility was off his shoulders, he had discovered no evidence of our being conspirators. He now treated us as friends. He even directed the car attendant to clean from the windows their accumulated dust.