полная версия

полная версияCharles Bradlaugh: a Record of His Life and Work, Volume 1 (of 2)

CHAPTER V

ARMY LIFE CONCLUDED

When his father died in 1852 Private Charles Bradlaugh came home on furlough to attend the funeral. He was by this time heartily sick of soldiering, and under the circumstances was specially anxious to get home to help in the support of his family. (This, one writer, without the slightest endeavour to be accurate even on the simplest matters, says is nonsense, because his family only numbered two, his mother and his brother!) His great-aunt, Elizabeth Trimby, promised to buy him out, and he went back to his regiment buoyed up by her promise. In September he was in hospital, ill with rheumatic fever, and after that he seems to have had more or less rheumatism during the remainder of his stay in Ireland; for in June 1853, in writing to his sister, apologising for having passed over her birthday without a letter, he says: "I was, unfortunately, on my bed from another attack of the rheumatism, which seized my right knee in a manner anything but pleasant, but it is a mere nothing to the dose I had last September, and I am now about again."

The letters I have by me of my father's, written home at this time, instead of teeming with fiery fury and magniloquent phrases as to shooting his officers,11 are just a lad's letters; the sentences for the most part a little formal and empty, with perhaps the most interesting item reserved for the postscript; now and again crude verses addressed to his sister, and winding up almost invariably with "write soon." After the father's death Mr Lepard, a member of the firm in which he had been confidential clerk for upwards of twenty-one years, used his influence to get the two youngest children, Robert and Harriet, into Orphan Asylums. While the matter was yet in abeyance Elizabeth seems to have written her brother asking if any of the officers could do anything to help in the matter, and on March 14th he answers her from Ballincollig: —

"I am very sorry to say that you have a great deal more to learn of the world yet, my dear Elizabeth, or you would not expect to find an officer of the army a subscriber to an Orphan Asylum. There may be a few, but the most part of them spend all the money they have in hunting, racing, boating, horses, dogs, gambling, and drinking, besides other follies of a graver kind, and have little to give to the poor, and less inclination to give it even than their means."

My father's great-aunt, Miss Elizabeth Trimby, died in June 1853, at the age of eighty-five. She died without having fulfilled her promise of buying her nephew's discharge; but as the little money she left, some £70, came to the Bradlaugh family, they had now the opportunity of themselves carrying out her intention, or, to be exact, her precise written wishes.12

The mother, in her heart, wanted her son home: she needed the comfort of his presence, and the help of his labour, to add to their scanty women's earnings; but she was a woman slow to forgive, and her son had set his parents' commands at defiance, and gone out into the world alone, rather than bow his neck to the yoke his elders wished to put upon him. She talked the matter over with her neighbours, and if it was a kindly, easy-going neighbour, who said, "Oh, I should have him home," then she allowed her real desires to warm her heart a little, and think that perhaps she would; if, on the other hand, her neighbour dilated upon the wickedness of her son, and the enormity of his offences, then she would harden herself against him. Her daughter Elizabeth wanted him home badly; and whilst her mother was away at Mitcham, attending the funeral, and doing other things in connection with the death of Miss Trimby, Elizabeth wrote to her brother, asking what it would cost to buy him out. He was instructed to write on a separate paper, as she was afraid of her mother's anger when she saw it, and wished to take the favourable opportunity of a soft moment to tell her. She was left in charge at home, and thinking her mother safe at Mitcham for a week, she had timed the answer to come in her absence. One day she had to leave the house to take home some work which she had been doing. On her return, much to her dismay, her mother met her at the door perfectly furious. The letter had come during the girl's short absence, and her mother had come home unexpectedly! "How dared she write her brother? How dared she ask such a question?" the mother demanded, and poor Elizabeth was in sad disgrace all that day, and for some time afterwards. This was the answer her brother sent, on June 22nd, from Cahir —

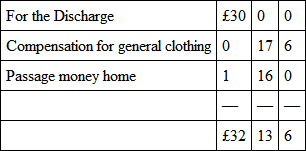

"As you wish, I send on this sheet what it would cost to buy me off; but I would not wish to rob you and mother like that.

or about £33.

"I could come home in regimentals, because clothes could be bought cheaper in London, and I would work like a slave; but do not think, my dear sister, I want to take the money from you and mother, though I would do anything to get from the army.

"We are under orders to march into the county of Clare to put down the rioters at Six Mile Bridge, in the coming election, and expect some fighting there."

The discharge was applied for in August, but I gather that Mr Lepard, who assisted my grandmother in the little legal matters arising out of Miss Trimby's death, was not very favourable to the project, and seems to have required some guarantee as to my father's character,13 before he would remit the money.

However, it was at length definitely arranged that the aunt's promise should be kept, and that her money should purchase the discharge according to her intentions. A thoroughly boyish letter gives expression to Private Bradlaugh's sentiments on hearing the good news. It is dated from "Cahir, 6th October 1853: —

"My Dear Mother, – When I opened your letter, before reading it I waved it three times round my head, and gave a loud 'hurra' from pure joy, for then I felt assured that all this was not a mere dream, but something very like reality. The £30 has not yet made its appearance on the scene. I shall be glad to see it, as I shall not feel settled till I get away. I am, however, rather damped to hear of your ill-health, but hope for something better. I have made inquiries about butter, but it is extremely dear, 1s. to 14d. per lb. in this county.

"When the £30 arrives I will write to let you know the day I shall be home. Till then, believe me, my dearest mother, your affectionate Son,

Charles Bradlaugh."Love to Elizabeth, Robert, and Harriet."

He did not have to wait long for the appearance of the £30 "on the scene," which speedily resulted in the following "parchment certificate: " —

"7th (Princess Royal's) Regiment of Dragoon Guards"These are to certify that Charles Bradlaugh, Private, born in the Parish of Hoxton, in or near the Town of London, in the County of Middlesex, was enlisted at Westminster for the 7th Dragoon Guards, on the 17th December 1850, at the age of 17-3/12 years. That he served in the Army for two years and 301 days. That he is discharged in consequence of his requesting the same, on payment of £30.

"C. F. Ainslie, Hd. Commanding Officer."Dated at Cahir, 12th October 1853.

"Adjutant General's Office, Dublin."Discharge of Private Charles Bradlaugh confirmed.

"14th October 1853. J. Eden,14 7th D. G.

"Character: Very Good."C. F. Ainslie, 7th D. Guards."The merely formal part of the discharge is made out in his own handwriting as orderly room clerk.

These three years of army life were of great value to my father. First of all physically: for a little time before he enlisted he had been half starved, and his health was being undermined by constant privation just at a time when his great and growing frame most needed nourishing. In the army he had food, which although it might be of a kind to be flouted by an epicure, was sufficiently abundant, and came at regular intervals. The obnoxious drill which he had to go through must have helped to broaden his chest (at his death he was forty-six-and-a-half inches round the chest) and harden his muscles, and so gave him the strength which served him so well in the later years of his life. He learned to fence and to ride, and both accomplishments proved useful in latter days. Fencing was always a favourite exercise with him and, in after days, when alone, he would also often exercise his muscles by going through a sort of sword drill with the old cavalry sabre, which is hanging on my wall to-day. Riding he at first abhorred, and probably any London East End lad would share his sentiments when first set upon a cavalry charger with a hard mouth; he was compelled to ride until the blood ran down his legs, and before these wounds had time to heal he had to be on horseback again. When he was orderly room clerk, and was not compelled to ride so often, then he took a liking for it, and then he really learned to sit and manage his horse. Often and often during the last years of his life he longed to be rich enough to keep a horse, so that he might ride to the House and wherever his business might take him within easy distance, and thus get the exercise of which he stood so urgently in need.

It was, too, while with his regiment in Ireland that Mr Bradlaugh first became acquainted with James Thomson, an acquaintance which soon ripened into a friendship which lasted for five-and-twenty years. In the quiet nights, whilst the private was on sentry duty, he and the young schoolmaster would have long serious talks upon subjects a little unusual, perhaps, amongst the rank and file; or in the evening, when Thomson's work was done, and Private Bradlaugh could get leave, they would go for a ramble together. They each became the confidant of the other's troubles and aspirations, and each was sure of a sympathetic listener.

That his regiment happened to be stationed in Ireland during the whole time he belonged to it was of immense importance to him. He learned the character and the needs of the Irish peasantry as he could have learned it in no other way. The sights he saw and the things he heard whilst he was in Ireland, as the story I cited a few pages back will show, produced in him such a profound feeling of tenderness and sympathy for the Irish people, that not all the personal enmity which was afterwards shown him by Irishmen could destroy or even weaken.

CHAPTER VI

MARRIAGE

Barely three short years away, yet how many changes in that short time. My father found, father, aunt, and grandmother dead; his little sister and brother – of five and eight years – in Orphan Asylums. Even his kind friend Mrs Carlile was dead, and her children scattered, gone to the other side of the Atlantic, to be lost sight of by him for many years. Of their fate he learned later that the two daughters were married, while Julian, his one time companion, was killed in the American War.

On his return my father's first endeavour was, of course, to seek for work, so that he might help to maintain his mother and sisters; but although he sought energetically, and at first had much faith in the charm of his "very good" character, no one seemed to want the tall trooper. After a little his mother, unhappily, began to taunt him with the legacy money having been used to buy his discharge; and although he thought, and always maintained, that the money was morally his, to be used for that purpose, since it was carrying out the intentions of his aunt expressed so short a time before her death, he nevertheless determined to, and in time did, pay every farthing back again to his mother, through whose hands the money had come to him. He was offered the post of timekeeper with a builder at Fulham, at a salary of 20s. a week; this Mrs Bradlaugh objected to, as taking him too far away from home.

One day he went, amongst other places, into the office of Mr Rogers, a solicitor, of 70 Fenchurch Street, to inquire whether he wanted a clerk. Mr Rogers had no vacancy for a clerk, but mentioned casually that he wanted a lad for errands and office work. My father asked, "What wages?" "Ten shillings a week," replied Mr Rogers. "Then I'll take it," quickly decided my father, feeling rather in despair as to getting anything better, but bravely resolved to get something. Not that he was in reality very long without work, for his discharge from the army was dated at Dublin, October 14th, 1853, and I have a letter written from "70 Fenchurch Street" on January 2nd, 1854, so that he could not have been idle for more than about two months at the most. There is no reference whatever in the letter to the newness of his situation, so that he had probably been with Mr Rogers some weeks prior to the 2nd January 1854. The solicitor soon found out that his "errand boy" had considerable legal knowledge and, what was even more important, a marvellous quickness in apprehension of legal points. At the end of each three months his salary was increased by five shillings, and after nine months he had intrusted to him the whole of the Common Law department. Very soon he was able to add a little to his income by acting as secretary to a Building Society at the Hayfield Coffee House, Mile End Road.

As soon as my father found himself in regular employment he began to write and speak again; but even as the busybodies turned the kind-hearted baker's wife against him a few years before, so now again they tried to ruin his career with Mr Rogers. Anonymous and malicious letters were sent, but they did not find in him a weak though good-hearted creature, with a fearful apprehension that the smell usually associated with brimstone would permeate the legal documents; on the contrary, he was a shrewd man who knew the value of his clerk, and treated the anonymous letters with contempt, only asking of my father that he should "not let his propaganda become an injury to his business."

Thus it was he took the name of "Iconoclast," under the thin veil of which he did all his anti-theological work until he became candidate for Parliament in 1868; thenceforward he always spoke and wrote under his own name, whatever the subject he was dealing with. Any appearance of concealment or secrecy was dreadfully irksome to him, though in 1854 he had very little choice.

About Christmas 1853 my father made the acquaintance of a family named Hooper, all of whom were Radicals and Freethinkers except Mrs Hooper, who would have preferred to have belonged to Church people because they were so much more thought of. She had great regard for her neighbours' opinion, and for that reason objected to chess and cards on Sunday. Abraham Hooper, her husband, must on such points as these have been a constant thorn in the dear old lady's side: he was an ardent Freethinker and Radical, a teetotaller, and a non-smoker. All his opinions he held aggressively; and no matter where was the place or who was the person, he rarely failed to make an opportunity to state his opinions. He was very honest and upright, a man whose word was literally his bond. He had often heard my father speak in Bonner's Fields, and had named him "the young enthusiast." He himself from his boyhood onward was always in the thick of popular movements; although a sturdy Republican, he was one of the crowd who cheered Queen Caroline; he was present at all the Chartist meetings at London; and he was a great admirer of William Lovett. On more than one occasion he was charged by the police whilst taking part in processions. He once unwittingly became mixed up with a secret society, but he speedily disentangled himself – there was nothing of the secret conspirator about him.

He was what might be called "a stiff customer," over six feet in height, and broad in proportion; and he would call his spade a spade. If you did not like it – well, it was so much the worse for you, if you could not give a plain straightforward reason why it should be called "a garden implement." "Verbosity" was lost upon him; he passed it over unnoticed, and came back to his facts as though you had not spoken. In his early old age he had rather a fine appearance, and I have several times been asked at meetings which he has attended with us, who is that "grand-looking old man." Although in politics and religion he was all on the side of liberty, in his own domestic circle he was a tyrant and a despot, exacting the most rigorous and minute obedience to his will.

His passionate affection for my father was a most beautiful thing to see. He had heard him speak, as a lad, many a time in Bonner's Fields, and from 1854 had him always under his eye. "The young enthusiast" became "my boy Charles," the pride and the joy of his life; and he loved him with a love which did but grow with his years. My father's friends were his friends, my father's enemies were his enemies; and although "Charles" might forgive a friend who had betrayed him and take him back to friendship again, he never did, and was always prepared for the betrayal – which, alas! too often came. He outlived my father by only five months: until a few years before his death he had never ailed anything, and did not know what headache or toothache meant; but when his "boy" was gone life had no further interest for him, and he willingly welcomed death.

And it was the eldest daughter of this single-hearted, if somewhat rigorous man, Susannah Lamb Hooper, whom my father loved and wedded. I knew that my mother had kept and cherished most of the letters written her by my father during their courtship, but I never opened the packet until I began this biography. These letters turn out to be more valuable than I had expected, for they entirely dispose of some few amongst the many fictions which have been more or less current concerning Mr Bradlaugh.

At the first glance one is struck with the quantity of verse amongst the letters. I say struck, because nearly, if not quite, all his critics, friendly and hostile, have asserted that Mr Bradlaugh was entirely devoid of poetic feeling or love of verse. With the unfriendly critics this assumed lack seems to indicate something very bad: a downright vice would be more tolerable in their eyes; and even the friendly critics appear to look upon it as a flaw in his character. I am, however, bound to confirm the assumption in so far as that, during later years at least, he looked for something more than music in verse; and mere words, however beautifully strung together, had little charm for him. His earliest favourites amongst poets seem to have been Ebenezer Elliott, the Corn Law rhymer, and, of course, Shelley. As late as 1870 he was lecturing upon Burns and Byron; later still he read Whittier with delight; and I have known him listen with great enjoyment to Marlowe, Spenser, Sydney, and others, although, curiously enough, for Swinburne he had almost an active distaste, caring neither to read his verse nor to hear it read. It is something to remember that it was my father, and he alone, who threw open his pages to James Thomson ("B. V.") at a time when he was ignored and unrecognised and could nowhere find a publisher to recognise the fire and genius of his grand and gloomy verse.

But to return to his own verses: he began early, and his Bonner's Fields speeches in 1849 and 1850 more often than not wound up with a peroration in rhyme; in verse, such as it was, he would sing the praises of Kossuth, Mazzini, Carlile, or whatever hero was the subject of his discourse. His verses to my mother were written before and after marriage: the last I have is dated 1860. I am not going to quote any of these compositions, for my father died in the happy belief that all save two or three had perished; but there is one that he sent my mother which will, I think, bear quoting, and has an interest for its author's sake. Writing in July 1854, he says: "I trust you will excuse my boldness in forwarding the enclosed, but think you will like its pretty style. I begged it from my only literary acquaintance, a young schoolmaster, so can take no credit to myself" —

"Breathe onward, soft breeze, odour laden,And gather new sweets on your way,For a happy and lovely young maidenWill inhale thy rich perfume this day.And tell her, oh! breeze softly sighing,When round her your soft pinions wreathe,That my love-stricken soul with thee vieingAll its treasures to her would outbreathe."Flow onward, ye pure sparkling watersIn sunshine with ripple and spray,For the fairest of earth's young daughtersWill be imaged within you this day.And tell her, oh! murmuring river,When past her your bright billows roll,That thus, too, her fairest form everIs imaged with truth in my soul."The "young schoolmaster" was, of course, James Thomson; and these verses express the thought which occurs again so delightfully in No. XII. of the "Sunday up the River."15

Another current fiction concerning my father is that he was coarse, rude, and ill-mannered in his young days. Now, to take one thing alone as a text: Can I believe that the love letters now before me that he wrote to my dear mother could have been penned by one of coarse speech and unrefined thought? The tender and respectful courtesy of some of them carries one back to a century or so ago, when a true lover was most choice in the expressions he used to his mistress. No! No one with a trace of coarseness in his nature could have written these letters.

Another and equally unfounded calumny, which has been most industriously circulated, concerns my father's own pecuniary position and his alleged neglect of his mother. I am able to quote passages from this correspondence which make very clear statements on these points; and the silent testimony of these letters, written in confidence to his future wife, is quite incontrovertible. In a letter written on the 17th November 1854, he says: —

"My present income at the office is £65, and at the Building Society £35, making about £100 a year, but I have not yet enjoyed this long enough to feel the full benefit of it. I am confident, if nothing fresh arises, of an increase at Christmas, but am also trying for a situation which if I can get would bring me in £150 per annum and upwards. Your father did not tell me when I saw him that I was extravagant, but he said that he thought I was not 'a very saving character,' so that you see, according to good authority, we are somewhat alike… I do not blame you for expecting to hear from me, but I was, as the Americans say, in a fix. I did not like to write, lest your father might think I was virtually taking advantage of a consent not yet given.

"You will, of course, understand from my not being a very careful young man why I am not in a position of healthy pockets, purse plethora, plenum in the money-box, so necessary to one who wishes to entangle himself in the almost impenetrable mysteries of 'house-keeping.'

"I don't know whether you were ever sufficiently charmed with the subject to make any calculations on the £ s. d. questions of upholstery, etc. I have, and after knocking my head violently against gigantic 'four posters,' and tumbling over 'neat fender and fire-irons,' I have been most profoundly impressed with respect and admiration for every one who could coolly talk upon so awful a subject."

From the foregoing letter it would appear that Mr. Hooper would not give a definite consent to the marriage; and a little later my father writes that he had again asked for the paternal approval, and draws a picture of "C. B." kneeling to the "krewel father." The consent asked for was apparently given this time, and plans and preparations for the marriage were made. On 20th March 1855 my father writes: —

"I also thought that it seemed a rather roundabout way of arriving at a good end, that I should take upon myself the bother of lodgers in one house, while mother at home intended to let the two upstairs rooms to some one else. I also thought that supposing anything were to happen either to separate me from the Building Society or to stop its progress, I might be much embarrassed in a pecuniary point of view with the burden of two rents attached to me. It therefore struck me, and I suggested to mother and Lizzie, whether it would not be possible, and not only possible but preferable, that we should all live in the same house as separate and distinct as though we were strangers in one sense, and yet not so in another. Mother and Lizzie both fully agreed with me, but it is a question, my dearest Susan, which entirely rests with you, and you alone must decide the question. I have agreed to allow mother 10s. per week, and if we lived elsewhere, mother out of it would have to pay rent, whilst ours would be in no way reduced. Again, if you felt dull there would be company for you, and I might feel some degree of hesitation in leaving you to find companionship in persons utterly strangers to both of us. There are doubtless evils connected with my proposal, but I think they are preventible ones. Mother might wish to interfere with your mode of arrangements. This she has promised in no way whatever to do. I leave the matter to yourself – on the ground of economy much might be said – at any rate my own idea is that we could not hurt by trying the experiment for a time; but do not let my ideas influence you in your decision: I will be governed by you: believe me, I only wish and endeavour to form a plan by which we may live happy and comfortably."