полная версия

полная версияThe Dog

During the application of the liniment, some diluted liquor arsenicalis may also be administered, and even the pills containing iodide of sulphur exhibited.

The fourth kind of mange is where the hair falls suddenly off in circular patches. For this any simple ointment, as the ung. cest. or no application at all is sufficient.

The fifth kind is the worst, especially where it attacks young pups. Almost all the hair falls off; and the poor little creature is thin, and nearly naked, while the surface of the body is covered with dark patches, and comparatively large pustules. If the dark patches be punctured, a quantity of venous and grumous blood exudes; but the wound soon heals. In full-grown dogs, the same form of disease seldom involves more than the top of the head, neck, and the entire length of the back; but it is precisely of the self-same character as in the more juvenile animal.

In both cases the treatment is the same. The dark pustules are to be cut into, which produces no pain; and the pustules are to be freely opened, which operation is attended with no apparent effects. The bare skin is to be then washed tenderly with warm water and a soft sponge, after which the body may be lightly smeared over with the ointment of camphor and mercury; see p. 265. This operation must be repeated daily. The liquor arsenicalis may be administered as drops, and pills of the iodide of sulphur likewise exhibited.

Where the dog is old, a cure invariably results; but it takes time to bring it about. Perhaps months may be thus consumed; and the practitioner will require a goodly stock of patience before he undertake the treatment of such a case. The proprietor, therefore, must be endowed with some esteem for the animal, before he can be induced to pay for all the physic it will consume. I cannot account for so virulent a form of skin disease affecting pups; but certain it is, that they have scarcely left the dam before its signs are to be detected. Probably it may be owing to their being weaned upon garbage or putrid flesh. Certain it is that the cure of creatures at this tender age greatly depends upon their previous keep. If it has for any known length of time been good and generous, the practitioner may undertake the case without fear; but if, on the other hand, the pup, though of a valuable breed, had lived in filth, never enjoyed exercise, and been badly nurtured, no entreaties should tempt the veterinarian to promise a restoration. It will certainly perish, not perhaps of the skin disease, but of debility.

Here I may for the present conclude my imperfect account of mange; again insisting that in every form of the disorder the food is to consist of vegetables, and every kind of flesh is to be scrupulously withheld, unless to pups in a very weakly condition. Blaine and Youatt speak of alteratives as necessary towards the perfection of a cure; but as I am simply here recording my experience, all I can say is, I have not found them to be required. Cleanliness – the bed being repeatedly changed – free exercise – wholesome, not stimulating food – and fresh water – are essential towards recovery. In no case should the dog suffering under these complaints be allowed to gorge or cram itself; but the victuals must be withdrawn the instant it has swallowed sufficient to support nature.

CANKER WITHIN AND WITHOUT THE EAR

Blaine treats of these two as different diseases. Youatt speaks of them as the same disease situated on different parts. As they differ in their origin and in their effects, however closely they may be united, I hold Blaine's arrangement to be the soundest, and therefore to that I shall adhere. Water-dogs are said to be the most liable to attacks of these disorders; but I have not found such to be the case. At the mouth of the river Ex, near Exeter, Devonshire, for instance, there are numerous dogs kept for the purpose of recovering the wild fowl, by shooting of which their masters exist during winter. Here is rather a wide field for observation; but among the many water-dogs there to be found, the canker both internal and external is unknown; whereas there is scarcely a dog kept in town, especially of the larger size, that does not present a well-marked case of canker. The London dog is, for the most part, over-fed on stimulating diet (flesh), and kept chained up, generally in a filthy state. The country dog gets plenty of exercise, being allowed to sleep in the open air where he pleases outside of his master's cottage, and has but little food, and very seldom any flesh. I scarcely ever have a sporting dog sent to me, on the approach of autumn, suffering from what their masters are pleased to term "foul," but canker within and without the ear are found to be included in the so-called disorder. Often am I desired to look at both long-haired and short-haired dogs, and find both kinds victims to these diseases; but canker without the ear, or on the flap of the ear, I never see without canker within the ear being also present. Canker on the flap of the ear, it is true, becomes the worst in short-haired dogs, because these animals have this part by nature more exposed to injury. Long-haired dogs, on the other hand, have the disease within the organ worst, because the warmth of their coats serves to keep hot and to encourage the disorder.

Therefore, we find on inquiry that neither breed of dogs is more liable or more subject to be attacked by a particular kind of canker; though in each kind there exist circumstances calculated to give a direction to the disease when once established. Authors speak of rounding the ear for external canker; that is, of taking a portion of the border away, so as to leave the flap of the ear the less for the operation; and fox-hounds are said to have the ears rounded to escape the ravages of the disorder. There are said to have been poor dogs subjected to a second and third rounding; till at length the entire ear has been rounded away, and the wretched beast has been at last destroyed; because man first fed it till it was diseased, and then was too heartless properly to study the nature of the affection which tormented the animal.

Let those who may feel disposed to question this view of external canker, ask themselves what it is which induces the dog to shake his head violently at first? For the brute must shake the head violently and frequently, before canker in the flap can be established. The disease is, in the first instance, thus mechanically induced. It has its origin in the violent action of the beast; and that action is the very one which ensues upon the animal being attacked by internal canker.

The dog shakes his head long before the eye can detect anything within the ear. By that action, in nine cases out of ten, we are led to inspect the part. The action is symptomatic of the disorder, and it is the earliest sign displayed. In the dog whose coat does not favor internal canker, it may, however, establish the external form of the disease; which being once set up, may afterwards even act as a derivative to the original disorder.

External canker is nothing more in the first stage than a sore established around the edge of the ear, in consequence of the dog violently shaking the head, and thereby hitting the flap of the ear with force against the collar, chain, neck, &c. Shaking, however, does not cure the annoyance. An itching within the ear still remains; which the dog, doubtless imagining it to be caused by some foreign body, endeavors to shake out. In consequence of the continued action, the sore is beaten more and more, till an ulcer is established; the ulcer extends, involves the cartilage which gives substance to the flap of the ear, and thus is created a new source of increased itching. The ulcer enlarges, becomes offensive; and he who is consulted, instead of seeking for the cause, begins by attending to the effect. Various remedies are employed to cure the flap of the ear; and each and all of these failing, the poor animal is at length rounded, and as books and teachers advise, rounded high enough up.

All the diseased parts are carefully cut away; but the disease appears again, and the wretched beast is rounded a second time. On this occasion the rounding is carried still deeper, the operator being resolved the knife this time shall take effect. The dog has little ear left when the disease appears again; and the master saying he wants his dog for the field – to shoot over, and not to look at – the remaining portion of the ear is removed, hoping for better luck this time. However, chances are now against them; they have cut beyond mere skin and cartilage, into the seat of flesh in goodly substance. Spite of the brutal use of the red-hot iron, the hemorrhage is great, and ulcers appear before the cicatrix is perfected. The miserable animal having nothing more that can be cut away, is then killed, being said to be incurably affected.

This is a true history, and can be substantiated by reference to all the authors who have hitherto written about the dog. It does not, therefore, depend solely upon the testimony of the present writer; but sad is the reflection, that all the pain and suffering thus occasioned was unnecessary. Canker without the ear cannot be established unless canker within the ear, in the first instance, exists. It may not be violent; it may be present only in an incipient stage, and never get beyond it; but in this state it is sufficient to annoy the animal, and make it shake its head. Doing this, however, it does enough to mislead the practitioner, and cause the death of the unfortunate animal.

When a dog is brought with canker in the flap, the first thing I order is a calico cap, to keep the animal from shaking the ear. I then give the person accompanying the creature a box of the mercurial and camphor ointment, ordering it to be well applied to the external ear thrice daily, with the intention of cooling the part. I do nothing absolutely to heal the ulcers beyond keeping the part from being shaken; for I have not yet met with a case in which the cartilage has been positively involved, however much authors may write about such a texture having suffered. I direct my chief attention to the healing of the internal ear, from which I trace all the evil to have sprung. For this purpose I give a bottle of the canker-wash, described a little further on, ordering it to be applied thrice daily, and rest contented as to the result.

With regard to internal canker, how virulent was the disorder, and to what lengths it used to progress, may be imagined from reading Blaine and Youatt; both of whom speak with terror of its effects, advising the use of agents for the recommendation of which I cannot account, excepting by the supposition that they were selected under the influence of fear. Most of the solutions advised are painful; but how far they were effective we may conjecture from the descriptions they have left us of the disease. They tell us that, as the disorder proceeds, it eats into the brain; either causing the dog to be destroyed, or driving it phrenetic. The poor animal, we are informed, leans the head upon the fore-feet, the diseased ear being pressed downwards, and continually utters a low moan, which at length rises into one prolonged howl. Of all this I know nothing; but I remember at college, when going the rounds with the Professor Simonds, on a Sunday morning, hearing one of those huge howls which are uttered by large dogs when enduring excessive torture. On my asking whence the sound proceeded, I was coolly informed by my teacher that he supposed Sam (the head groom) had been pouring some dressing into the ear of a dog that had got canker. Of what the dressing that had occasioned such pain was composed, I never inquired; but we may judge of its power to destroy the bone, from the extent of the agony which it produced. No wonder, when such powerful agents were employed, the bone, the brain, or any other part, was affected.

Thank heaven! there is one good custom prevalent in this disease – dogs affected with it are brought to us early. Often, when the animal is only observed to be constantly shaking and scratching the ear, the proprietors bring the dog for us, to remove something from the interior of the organ. At other times, and with the most careless or unobservant masters, the dog is brought under our notice with a blackened discharge within the convolutions of the ear, and a slight smell, like decayed cheese, proceeding from it. A crackling sensation is then imparted to the fingers when the base of the ear below the flap is manipulated; the necessary pressure sometimes drawing forth an expression of pain. A worse case than this I have not encountered; though how common canker has been in my practice may be conjectured from my keeping a two-gallon stock-bottle of the wash in my surgery, and a label, for the bottles in which it is sent out, within my drawers. The mode of administering this wash is admirably described by Youatt, from whose pages I transcribe it: —

"Some attention should be paid to the method of applying these lotions. Two persons will be required in order to accomplish the operation. The surgeon must hold the muzzle of the dog with one hand, and have the root of the ear in the hollow of the other, and between the first finger and the thumb. The assistant must then pour the liquid into the ear; half a tea-spoonful will usually be sufficient. The surgeon, without quitting the dog, will then close the ear, and mould it gently until the liquid has insinuated itself as deeply as possible into the passages of the ear."

The warming of the fluid I find to be unnecessary; and there is something to be added to the above direction, when the wash I advise is employed. After one ear is done, let it be covered closely with the flap, and the other side of the head turned upward without releasing the dog. When both are finished, take a firm hold of the dog, and fling him away to any distance the strength you possess is capable of sending the animal; for the instant the dog is loose, it will begin shaking its head, and, as the canker-wash I employ contains lead, wherever a drop falls, a white mark or spot, as the liquid dries, will be left behind.

CANKER WASH

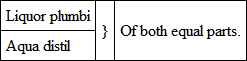

Youatt speaks of the liquor plumbi as a dangerous agent to the dog, and advises for canker that a scruple be mixed with an ounce of water; but in opposition to that esteemed author's recommendation, I have employed the liquor plumbi pure, with the best effect, in extreme cases; though, in ordinary disease, the above is sufficiently strong; and in medicine it is a maxim that a sufficiency is enough.

I give to the animal, as a general rule, no medicine to take; but invariably recommend the dog to be kept on vegetable diet; for, inasmuch as meat is the sole cause of the disorder, however potent may be the drugs employed for the cure, it is imperative for its eradication that the cause be removed.

Sometimes, in consequence of the violent shaking of the head, serous abscesses of considerable size form inside the flaps of the ears. This mostly happens with large dogs, and the abscesses are hot and soft, being excessively tender. The animal does not like them to be touched, or even looked at, but is frequently shaking the head, and howling or whining afterwards.

The remedy in these cases is equally simple and efficient. The person who undertakes to remedy the evil, first, by way of precaution, tapes the animal; that is, he forms a temporary muzzle, by binding a piece of tape thrice firmly round the creature's mouth. He then places the dog between his knees, and turning up the ear, with a small lancet makes quickly an opening in what then is the superior part of the sac in the inverted ear. This is necessary, because, if the opening were made inferiorly, all the fluid would escape, and the side of the emptied sac would collapse. If the point of the knife even could be introduced into an incision made upon the lower part of the ear, it would not be so easy to cut speedily from below upward, as to push the blade from above downwards. Well, the opening being made with the lancet, a little fluid escapes; but no pressure being put on the sac, the major portion is retained. The operator then takes a straight probe-pointed bistoury, and having introduced it into the orifice, by making only pressure, instantly divides the sac. Frequently considerable fluid escapes; the beast operated upon makes up its mind for a good howl; but, finding the affair over before its mouth was moulded to emit the sound, the cry is cut short, and the dog returns to have the tape removed, that it may lick the hand that pained it.

After the enlargement is slit up, nothing more is required than to fill the sac for a day or two with lint soaked in the healing fluid; and when suppuration is established the lint may be withdrawn, and the wound, if kept clean, left to nature.

THE EYE

Most writers describe a regular series of disorders associated with the eye of the dog. I must be permitted to recite only those which I have witnessed; and surely, if the diseases which the writers alluded to above have mentioned do exist, I must have encountered some solitary instance of each of them; instead of which, I have been honored by the confidence of all classes, and have after all to confess I have not witnessed a specimen of genuine ophthalmia in this animal.

Cataract. – This derangement of the visual organ is very common with the dog. Every old animal that has lost his eyesight is nearly certain to be blind from cataract. The optic nerve appears to have retained its health long after the crystalline lens has parted with its transparency. The latter becomes opaque, while circumstances allow us to infer the former is yet in vigor; for certainly dogs do see through lenses, the milky or chalky aspect of which would justify us in pronouncing the sight quite gone. There is no precise time when cataract makes its appearance. It may come on at any period or at any age. It may be rapid or slow in its formation; but from its generally known habit, we should be inclined to say it was rather slow than otherwise; though upon this point the author can speak with no certainty. No breed appears to be specially liable to it, but all seem to be exposed to it alike. The small-bred, house-kept, high-fed dogs, however, are those most subject to be attacked by it; for, in these kinds of animals, on account of the derangement of the digestive organs, the eyes seem to be disposed to show cataract earlier than in the more robust creatures of the same breed.

The cause of this affection is, in the horse, usually put down to blows; but, in the dog, we dare not say the disorder is thus produced. The dog is more exposed to the kicks and cuffs of domestics than is the horse; the violence done upon the first-named animal being less thought about, and therefore less likely to be observed. But that the disease takes its origin in any such inhumanity the author has no proof, and no intention of insinuating an accusation against a class, who being generally ignorant, have therefore the less chance of a reply.

The disease seems to be the natural termination of the animal's eyesight; and, though the author has seen the iris ragged-looking, as though acute ophthalmia had loosed its ravages upon the delicate structures of the eye, nevertheless he has in vain endeavored to detect the presence of that disease.

Were ophthalmia common enough to have produced one-half of the cataracts which are to be witnessed by him who administers to the affections of the canine species, surely I must have met with it; as not being a very brief disorder, but one which by its symptoms is sure to make itself known, I must have encountered it in one of its numerous stages. However, not having seen it, and still being anxious of tracing cataract to its source, the author has been induced to attribute it to the influences of old age, high breeding, or too stimulating a diet.

Medicine having appeared to do injury rather than to produce benefit, the author has generally abandoned it in these cases; whereas those measures which are within the reach of every proprietor, such as change of abode, attention to necessary cleanliness without caudling in the bed, wholesome food, and a total abstinence from flesh, added to the daily use of the cold bath with a long run, and constant employment of a penetrative hair-brush to the skin afterwards, have seemed to stay the ravages of the disorder; and on these, therefore, the author is inclined to place his entire dependence.

Gutta Serena. – The author has seen one or two cases of this affection. One was present with disease of the brain, to the increase of which it was clearly traceable. The other was attributable to no known cause; but as blows on the head are beyond all doubt ascertained to produce this affliction, the author in his own mind has no doubt of its origin. A temporary affection of this nature is also constantly witnessed when the dog falls down in a fit, or rather faints from weakness; as when a female is rearing an undue number of pups, or when a dog has been too largely bled, or retained too long in the warm bath.

In the last cases, the gutta serena departs as the animal recovers; but in the first-named, sometimes it is constant, and no medicine appears to affect it for good or for evil. The author, therefore, does nothing in such cases beyond giving general directions, as in the instance of cataract.

Gutta serena is known by the organ being perfectly clear, but the iris remaining permanently fixed. The introduction of sudden light produces no effect on it; neither, unless the current of air be agitated, does the eyelid move. Towards the latter stage the eye changes color; but when it first occurs, a person without experience would prefer the eye in this state, because it looks so thoroughly bright and transparent. The aspect of these eyes is known to those who are much among animals, and the carriage of the body is recognised as altered when a creature becomes blind; besides which, trust him alone, and his running against different obstacles, as well as his manner of walking, will declare the truth.

Simple Ophthalmia. – To this disorder of the eye the dog is very susceptible. It may be caused by dust, dirt, thorns, or portions of leaves getting into the eyes; the symptoms are, constant closing of the lid, and perpetual flowing of the tears. Though the eye be closed, the lid is never quiet; but is being, during the entire period, spasmodically, though partially, raised to be shut again, or in perpetual movement. If the lids are forced asunder, the conjunctiva or mucous membrane forming the inner lining of the lid is seen to be inflamed; while the same membrane covering the ball of the eye is perceived to be of a white color, and perfectly opaque.

The cure in this instance is always, first, to remove the cause of the injury, and then to apply some of the remedies in the manner mentioned hereafter.

The conjunctiva in the dog is very sympathetic with the mucous membrane lining the stomach. The interior of the stomach may be inflamed, and the eye sometimes exhibits no sign of sympathy; but more often, as in distemper or rabies, it will denote the existence of some serious disorder. So if the animal's digestive powers are weakened by an undue quantity of purgative medicine, the eyes will assume all the symptoms of distemper, even to the circular ulcer in the centre of the organ. However, in instances of this kind nothing need be done for cure; the major disorder being subdued, the minor one subsides.

No matter how virulent the disease of the eye may appear to be – even though it should become perfectly opaque – let it alone: any meddling does injury. No bathing or medicaments can hasten the cure. Although it should ulcerate in the centre, and the terrible appearance of the eye be seconded by the entreaties of the proprietor, still I caution you to continue quite passive. Touch the ulcer with nitrate of silver, as is the common practice, and the eye will most likely burst. The aqueous humor will escape, and a large bunch of fungus will start up in the place of the ulcer occupied. This fungus, if let alone, may fade away as the stomach returns to health; but a white spot is established in its place to remind you of your officiousness.

Nevertheless, simple ophthalmia occasionally will appear when nothing can be detected to affect the stomach; probably owing to large dogs chasing through brush-wood, or those of the smaller breeds hunting through long grass. Then a square of soft lint, formed by doubling a large piece several times, is laid upon the painful organ, and kept wet with the following lotion: —