полная версия

полная версияCharles Bradlaugh: a Record of His Life and Work, Volume 2 (of 2)

As for his general tone of feeling on the questions which turn in an equal degree on feeling and judgment, it is well illustrated by the last non-personal speech he made in the House in the period of his conditional tenure of his seat. It was delivered on 28th March, and was on the subject of flogging in the army: —

"Mr Bradlaugh said he wished to say a few words on this matter from a different point of view than other members who had spoken. He had been a private in the army during the time that flogging was permitted for offences now described as trivial, and he heard the same argument used, that it would cause a relaxation of discipline if flogging were abolished. If hon. members opposite knew the feeling of the soldiers at that time it would have much modified some of the speeches delivered to-day (hear, hear); and the hon. member for Sunderland (Sir H. Havelock-Allan) would be surprised to hear the number of letters he had received from private soldiers, asking him to speak on this subject to-day. There was a feeling of utter detestation against the punishment, not simply on the part of the men who were likely to suffer from it, but on the part of every one else. Private soldiers in England occupied a position which no other private soldier in the whole of Europe occupied, and he did not know any other country in the whole world where it was a disgrace to wear the uniform of your country. He remembered upon one occasion he went into an hotel in a great city and ordered a cup of coffee, and was told that he could not be served because he wore the uniform of his country. All punishments which made soldiers seem less reputable than their fellow-citizens ought to be abolished. He asked the Government to allow nothing whatever to influence them in favour of this most degrading punishment. The men who once felt the lash were not loyal to any command, and they felt a bitterness and an abhorrence of every one connected with the ordering of the punishment. If they flogged a man engaged on active service, he was either a good man or a bad man, a man of some spirit or none at all. If he were a man of any spirit, there were weapons in his hands, and he might use them for purposes of revenge. The hon. and gallant member for Wigton Burghs talked of men who preferred the lash. The army would be far better without such men. (Mr Childers: Hear, hear.) He had seen the lash applied, the man tied up, and stripped in the sight of his comrades; he had seen the body blacken and the skin break; he had heard the dull thud of the lash as it fell on the blood-soddened flesh, and he was glad of having the opportunity of making his voice heard against it to-day, and trusted that nothing would induce the Government to retain under any conditions such a brutal punishment. (Cheers.)"

And it was with these matters in their knowledge that a majority of the House of Commons subjected him for five years to an extremity of wanton injustice of which it is still difficult to think without burning anger. The story of that injustice must now be separately told.

CHAPTER III.

THE PARLIAMENTARY STRUGGLE

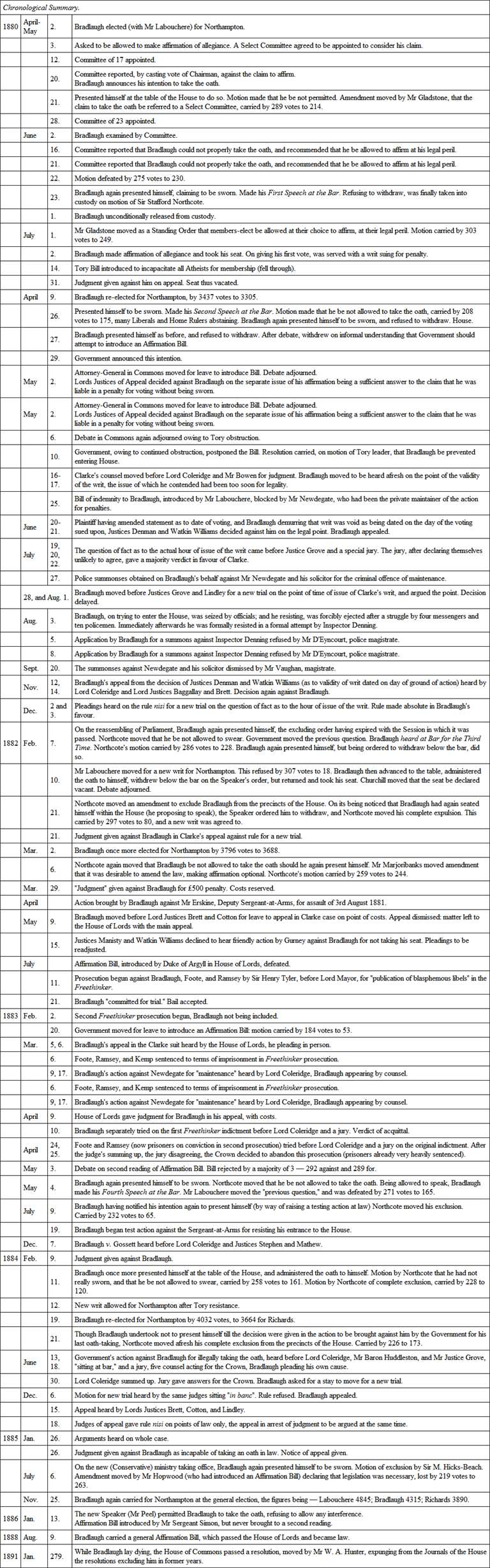

In the general election of 1880 Bradlaugh was at length elected member for Northampton. He had fought the constituency for twelve years, and had been defeated at three elections, at one of which he was not present. As has been made plain from the story of his life thus far, it was his way to carry out to the end any undertaking on which he entered, unless he found it to be wholly impracticable; and he was very slow to feel that an aim was impracticable because it took long-continued effort to realise it. He seems first to have thought of standing for Northampton about 1866. At that time Northampton was already reckoned a likely Radical constituency, not so much on account of its Parliamentary record as on the strength of the Radical element in its population. The trouble was that for long the bulk of the workers were not electors. His eloquence could win him a splendid show of hands in the market-place, but the polls told a different tale. The Whiggish middle classes were in the main intensely hostile to him, on political as well as on religious grounds; and the influence of pastors and masters alike was zealously used against him. After the passing of the Household Suffrage Act of 1868, however, the constituency became every year more democratic. The Freehold Land Society, some of whose founders and leading members were among his most devoted and capable followers, created year after year scores of freeholds, the property of workers, in a fashion that has finally made Northampton almost unique among our manufacturing towns. The electorate, which in 1874 had stood at 6829, had in 1880 risen to 8189; and of these it was estimated that 2,500 had never before voted. Of the new voters, the majority were pretty sure to be Radicals, and as Bradlaugh's hold on the constituency had grown stronger with every struggle, it began to be apparent to many of the "moderate Liberals" that a union between their party and his must be accepted if the two seats were not to remain in Tory hands. In the early spring, however, the confusion of candidatures seemed hopeless. Mr (now Sir) Thomas Wright of Leicester stood as a Liberal candidate at the request of a large body of the electors, and though not combining with Bradlaugh, deprecated the running of a second and hostile Liberal candidate. Other Liberals, however, brought forward in succession three candidates, of whom the once well-known Mr Ayrton was the most important. He, however, failed to gain ground, partly by reason of the qualities which had made him a disastrous colleague to Mr Gladstone's ministry, partly by reason of coming to grief in a controversy with Bradlaugh as to the facts of the agitation for a free press, and free right of meeting in Hyde Park, in regard to which Mr Ayrton claimed official credit. His candidature finally fell through when he met with an accident. A Mr Hughes was brought forward, only to be removed from the contest by an attack of illness. Mr Jabez Spencer Balfour, of recent notoriety, made a very favourable impression, but could not persuade "moderates" enough that the Liberals ought to unite with the Radicals. A little later Mr Labouchere was introduced, and giving his voice at once for union, found so much support that Mr Wright, with great generosity and public spirit, shortly withdrew, giving his support to the joint candidature of Bradlaugh and Labouchere, who stood pretty much alike in their Radicalism, though the latter was described in the local Liberal press as the "nominee of the moderate Liberals." As he explained in his own journal, a man who was a moderate Liberal in Northampton would rank as a Radical anywhere else. The joint candidature once agreed upon, victory was secure.

The Tory candidates were the former sitting members, Mr Phipps, the leading local brewer, and Mr Merewether, a lawyer. Their platform opposition was not formidable, and the greatest play on their side was made by the clergy and the press, who sought to make the contest turn as far as possible on Bradlaugh's atheism and on his Neo-Malthusianism. Nearly all the Established Church clergy, and some of the Nonconformists preached fervently against the "infidel." On the Sunday before the election the vicar of St Giles' intimated that "to those noble men who loved Christ more than party, Jesus would say, 'Well done!'" and on the day before the poll many thousands of theological circulars were showered upon the constituency. On the other hand, the deep resentment of Lord Beaconsfield's foreign policy felt by a great part of the nation led to unheard-of concessions on the part of the Nonconformists. The late Mr Samuel Morley, a representative Dissenter, wealthy and pious, being appealed to for an expression of opinion on the Northampton situation, sent to Mr Labouchere a telegram – soon repented of – "strongly urging necessity of united effort in all sections of the Liberal party, and the sinking of minor and personal questions, with many of which I deeply sympathise, in order to prevent the return, in so pronounced a constituency as Northampton, of even one Conservative." At the same time Mr Spurgeon was without the slightest foundation described in the Tory press as having said, with regard to the fight at Northampton, that "if the devil himself were a Liberal candidate, he would vote for him;" and it was supposed that the anecdote affected some votes.

But before any of these episodes had occurred, Bradlaugh was tolerably well assured of victory. His organisation, then controlled by his staunch supporter Councillor Thomas Adams, who lived to be Mayor of Northampton, was perfect; and he knew his strength as nearly as a candidate ever can who has not already been elected. The combination of his forces with those of Mr Labouchere of course strengthened him; yet such was still the strength of religious animosity that though the joint candidature stood on the footing of a strict division of votes, every elector having two, for the two seats, the Liberal press still encouraged "plumping," and many then, as later, voted for Mr Labouchere who would not vote for Bradlaugh, thus provoking a smaller number of the latter's supporters to "plump" for their man in turn. The result was that the election figures stood: – Labouchere (L.) 4518; Bradlaugh (R.) 3827; Phipps (C.) 3152; Merewether (C.) 2826.

No sooner were the results known throughout the country than the Northampton election became a theme of special comment, and of course of special outcry from the defeated party. One journal, the Sheffield Telegraph, which about the same time described the Scriptural phrase about the dog and his vomit as a "popular, though somewhat coarse saying," designated Bradlaugh as "the bellowing blasphemer of Northampton." Mr Samuel Morley was hotly assailed, and promptly wrote to the Record a pitiful letter of recantation, which ended: —

"No feeling of pride prevents my saying that I deeply regret the step I took, which was really the work of a moment; and I feel assured that no one who knows me will doubt that I view with intense repugnance the opinions which are held by Mr Bradlaugh on religious and social questions."

To which Mr Bradlaugh in his own journal replied that he had had no part whatever in the appeal to Mr Samuel Morley, and that he would have been elected all the same if Mr Morley had done nothing, adding the following: —

"We have no knowledge of the opinions of Mr Morley except that he is reputedly very rich, and therefore exceedingly good; but we must express in turn our intense repugnance to the conduct of Mr Morley, who having accidentally been betrayed into an act of kindness to a fellow-creature, regrets the act when pressure is brought to bear upon him by a pack of cowardly and anonymous bigots, and couples the public expression of his regret with a voluntary insult to one for whom Mr Morley publicly expressed great respect on the only occasion on which the two have yet come publicly in contact."

Mr Spurgeon, who had been quite falsely accused of avowing readiness to welcome the devil as a Liberal candidate, had the manliness to declare, while indignantly repudiating that latitudinarian doctrine, that Mr Bradlaugh's claims to be returned to Parliament were not to be measured by his piety or orthodoxy.

§ 2But the question was soon carried into a greater arena. The elections were over in April; on 3rd May Parliament assembled, and Bradlaugh's first problem was to choose his course in the matter of the oath of allegiance, the taking of which by members of Parliament is still made a condition of their taking their seats. It has long been felt by the thoughtful few, even including Theists, that oath-taking, a barbaric and primevally superstitious act under all circumstances, is gratuitously absurd in the case of admission to Parliament, where it serves to bring about the maximum of religious indecorum without in any way affecting the action of anybody. Originally set up in the reign of Elizabeth, the Parliamentary oath was maintained in the interest of disputed dynasties, though it was notoriously taken by hundreds of men who were perfectly ready to overthrow, if they could, the dynasty to which they swore allegiance. Now that there is no longer any question of rival dynasties, and that no instructed person disputes the power of Parliament to abolish the Monarchy, the oath of allegiance is maintained by the stolid unreason which supports the monarchic tradition all round. State after State has abandoned the practice as absurd; but Britain clings to it with hardly even a demur, save from men of the chair. France since 1870 has had neither oath nor affirmation, though, if oaths could be supposed to count for anything, the Republic might fitly have exacted them. Since 1868 affirmation has been substituted for the Parliamentary oath in Austria; and congressmen and senators in the United States have their choice between swearing and affirming. Neither oath nor affirmation is exacted in the German Reichstag, though the members of the Prussian Diet, like those of the States General of Holland, still swear. In Italy, the performance is attenuated to the utterance of the one word "Giuro," "I swear." In Spain, where it has never deterred rebellion, the oath, as might be expected, remains mediævally elaborate.

Before Bradlaugh's time the oath in England had been adapted to the requirements of Catholics, Quakers, and Jews successively, the resistance increasing considerably in the last case. O'Connell's refusal to take the Protestant oath of supremacy in 1829, when there were three separate oaths – one of allegiance, one of supremacy, and one of adjuration – led to the passing of an Act permitting Catholic members to take the Catholic oath, already provided under the Catholic Relief Act for use in Ireland. Protestant public opinion avowedly regarded all Irish Catholics with distrust as being disaffected, but the Tory leaders being committed to Catholic Emancipation, the resistance was overpowered. The next extension took place under Whig auspices.

In 1833 the Quakers, who in the case of Archdale in 1699 had been held incapable of sitting in Parliament by reason of their refusal to swear, were allowed to affirm, first by resolution of the House, later by Act. This was done at the instance of a Quaker member, Sir Joseph Pease, who besides being rich enjoyed personally the respect latterly accorded to his sect by those which formerly persecuted it.

Then came the case of the Jews, first raised in the person of Baron Lionel Nathan de Rothschild, in 1850. There was now a triple Protestant oath, and an alternative Catholic oath, the theoretically dangerous church being allowed to swear in its own way; but for the small community of Jews there was no formula, and the Jewish banker had to choose between exclusion and swearing "on the true faith of a Christian." He omitted these words from his oath, and was accordingly declared disentitled to sit, the House at the same time formally resolving to take Jewish disabilities into its consideration at the earliest opportunity in the next Session. In 1851, another Jew, David Salomons, returned for Greenwich, refused to take the oath in the Christian form, formally resisted the Speaker's ruling against him, was formally removed, and was excluded from his seat. Not till 1858 was the relief given. In that year a single (Christian) oath was substituted for the triple asseveration of the past, and on the re-elected Baron Lionel again refusing it, he was allowed, by resolution of the House, to swear without the Christian formula. In 1859 he, with Baron Mayer Amschel de Rothschild and Salomons, was again sworn theistically. Finally, in 1866, by the Parliamentary Oaths Act, the oath was made simply theistic for all, the familiar expletive "So help me God" being held sufficient to associate the First Cause ethically with the proceeding in hand.

This movement was doubtless due to a certain semi-rational perception of the futility of oaths in general, as being a vain formality to honest men, and a vain barrier to others. Sir William Hamilton, a thinker so fervent in his instinctive Theism that he undid his philosophy to accommodate it, had in his day created a strong impression by his essays (1834-5), on the right of Dissenters to be admitted into the English universities, in which he emphatically reiterated the declaration of Bishop Berkeley – made when the oath test was in fullest use – that there is "no nation under the sun where solemn perjury is so common as in England." "If the perjury of England stand pre-eminent in the world," said Hamilton, "the perjury of the English Universities, and of Oxford in particular, stands pre-eminent in England." Doctrine like this had made for an abolition of oaths which could easily be classified as "unnecessary," and for the simplification of those retained; but though the very step of reducing the act of imprecation to a curt conventional form meant, if anything, the belittling of the act of imprecation as such, the Parliamentary formula had for half a generation remained unchallenged. John Mill had in 1865 sworn "on the true faith of a Christian," and a good many Agnostics and Positivists have since unmurmuringly invoked the unknown God. It was left for Bradlaugh to attempt a departure from the course of dissembling conformity. When he stood for Northampton in 1868 (as he stated in answer to Mr Bright on the second select committee of 1880), he had gravely considered the question of oath-taking, there being then no possibility of affirmation. Believing now that he had the right to affirm under the Act which permitted affirmation to witnesses, he felt bound to exercise it.

As every step in his action has been and still is a subject of obstinate misconception and wilful falsehood, the story must be here told with some minuteness. The usual statement is that he "refused" to take the oath of allegiance. He did no such thing. A professed Atheist, he had been the means of bringing about the legal reform which enabled unbelievers to give evidence on affirmation, albeit the form of enactment was, to say the least, invidious. A great difficulty is felt by many Christians in regard to the abolition of the oath, in that they fear to open the way for false testimony by witnesses who would fear to swear to a lie, but do not scruple to lie on mere affirmation. It is for Christians to take the onus of asserting that there are such people among their co-religionists; and they have always asserted it in the House of Commons when there is any question of dispensing with oaths. And it was on this plea that the first Act framed to allow unbelievers to give evidence on affirmation was made to provide that the judge should in each case satisfy himself that a witness claiming to affirm was not a person on whom an oath would have a binding effect. That is to say, he was to make sure that the witness was not a knavish religionist trying to dodge the oath, in order to lie with an easy mind. It was the duplicity of certain believers, and not the duplicity of unbelievers, that was to be guarded against, though, of course, the only security against the lying of believers in answer to the judge was that a known conformist would be afraid publicly to pretend that he had scruples against the oath. But the main effect of the clause, framed to guard against pious knavery, was to stigmatise unbelievers as persons on whom an oath would have "no binding effect." An ill-conditioned judge was thus free to insult Freethinking witnesses, and even a just judge was free to embarrass them by an invidious question, since the bare wording of the Act enabled and even encouraged the judge to ask them – not, as he ought to have done, whether the oath was to them unmeaning in respect of the words of adjuration, but – whether the oath as a whole would be "binding on their conscience."121 While recognising the invidiousness of such a question, Bradlaugh always claimed to affirm in courts of law, though to him, as to most professed rationalists, the repetition of an idle expletive was only a vexation, and in no way an act of deception, when made the inevitable preliminary to the fulfilment of any civic duty. He had openly avowed his opinions, and if the oath was still exacted, the responsibility lay with those who insisted on it. On his return to Parliament he felt that not only would it be inconsistent for him to take the oath if he could avoid it, but it would be gratuitously indecorous, from the point of view of the believing Christian majority. Sitting in the house before the "swearing-in," he remarked to Mr Labouchere that he felt it would be unseemly for him to go through that form when he believed he was legally entitled to affirm. And in this belief, it must always be remembered, he had the support of the former Liberal law officers of the Crown, who had privately given it as their opinion122 that he was empowered to affirm his allegiance under the law relating to the affirmation of unbelievers. With that opinion behind him, he was in the fullest degree entitled – nay, he was morally bound as a conscientious rationalist – to take the course he did. Other rationalists, real or reputed, were returned to the same Parliament. Professor Bryce, as candidate for the Tower Hamlets, had been assailed as an Atheist, and was yet returned at the head of the poll. Mr Firth had been similarly attacked, but was nevertheless carried in Chelsea. Neither of these gentlemen, however, made any public avowal, direct or indirect, of heresy. Mr John Morley, who was justifiably regarded as a Positivist or Agnostic on the strength of his writings, when elected later made no demur to the oath; and Mr Ashton Dilke, who afterwards avowed his heterodoxy in the House of Commons,123 also took it without comment. It was left to Bradlaugh to fight the battle of common sense – I might say of common honesty, were it not that long usage has in these matters wholly vitiated the moral standards of the community, and honourable men are free to do, and do habitually, things which, abstractly considered, are acts of dissimulation.

§ 3Bradlaugh's first formal step after obtaining the opinion of the last Liberal law officers and privately consulting the officials of the House, was to hand to the Clerk of the House of Commons, Sir Thomas Erskine May, on May 3rd, a written paper in the following terms: —

"To the Right Honourable the Speaker of the House of Commons.

"I, the undersigned Charles Bradlaugh, beg respectfully to claim to be allowed to affirm as a person for the time being by law permitted to make a solemn affirmation or declaration, instead of taking an oath."

He had already explained, in answer to the questions of the Clerk, that he made his claim in virtue of the Parliamentary Oaths Act, 1866, the Evidence Amendment Act, 1869, and the Evidence Amendment Act, 1870, which "explains and amends" the Act of 1869. The Clerk formally communicated these matters to the Speaker (Sir Henry Brand), who then invited Bradlaugh to make a statement to the House with regard to his claim. Bradlaugh replied:

"Mr Speaker, – I have only now to submit that the Parliamentary Oaths Act, 1866, gives the right to affirm to every person for the time being permitted by law to make affirmation. I am such a person; and under the Evidence Amendment Act, 1869, and the Evidence Amendment Act 1870, I have repeatedly for nine years past affirmed in the highest Courts of Jurisdiction in this realm. I am ready to make the declaration or affirmation of allegiance."

The Speaker thereupon requested him to withdraw, and formally restated the claim to the House, remarking that he had "grave doubts" on the matter, and desired to refer it to the House's judgment. On behalf of the Treasury bench, Lord Frederick Cavendish, remarking that the advice of the new law officers of the Crown was not yet available, moved that the point be referred to a Select Committee. Sir Stafford Northcote, the Tory leader in the Commons, was at this stage not actively hostile. A man of well-meaning and temperate though meagre quality, made up of small doses of virtues and capacities, well fitted to be a country gentleman, but of too thin stuff and too narrow calibre to be either a very good or a very bad statesman, he was a Conservative by force of tradition and mental limitation, and a partisan leader in respect of his pliability to his associates. As his biographer puts it, he was "not recalcitrant to compromise" in matters of party strategy and leadership. Being personally willing to substitute affirmation for oath,124 he seconded the Liberal motion without any show of animus, and only some of his minor followers, as Earl Percy and Mr Daniel Onslow, sought to effect the adjournment of the debate. This attempt, however, was not pressed to a division, and the Select Committee was agreed to.