полная версия

полная версияAndré

William Dunlap

André

WILLIAM DUNLAP:

FATHER OF THE AMERICAN THEATRE

(1766-1839)

The life of William Dunlap is full of colour and variety. Upon his shoulders very largely rests the responsibility for whatever knowledge we have of the atmosphere of the early theatre in America, and of the personalities of the players. For, as a boy, his father being a Loyalist, there is no doubt that young William used to frequent the play-house of the Red Coats, and we would like to believe actually saw some of the performances with which Major André was connected.

He was born at Perth Amboy, then the seat of government for the Province of New Jersey, on February 19, 1766 (where he died September 28, 1839), and, therefore, as an historian of the theatre, he was able to glean his information from first hand sources. Yet, his monumental work on the "History of the American Theatre" was written in late years, when memory was beginning to be overclouded, and, in recent times, it has been shown that Dunlap was not always careful in his dates or in his statements. George Seilhamer, whose three volumes, dealing with the American Theatre before the year 1800, are invaluable, is particularly acrimonious in his strictures against Dunlap. Nevertheless, he has to confess his indebtedness to the Father of the American Theatre.

Dunlap was many-sided in his tastes and activities. There is small reason to doubt that from his earliest years the theatre proved his most attractive pleasure. But, when he was scarcely in the flush of youth, he went to Europe, and studied art under Benjamin West. Throughout his life he was ever producing canvases, and designing, and his interest in the art activity of the country, which connects his name with the establishment of the New York Academy of Design, together with his writing on the subject, make him an important figure in that line of work.

On his return from Europe, as we have already noted, he was fired to write plays through the success of Royall Tyler, and he began his long career as dramatist, which threw him upon his own inventive resourcefulness, and so closely identified him with the name of the German, Kotzebue, whose plays he used to translate and adapt by the wholesale, as did also Charles Smith.

The pictures of William Dunlap are very careful to indicate in realistic fashion the fact that he had but one eye. When a boy, one of his playmates at school threw a stone, which hit his right eye. But though he was thus early made single-visioned, he saw more than his contemporaries; for he was a man who mingled much in the social life of the time, and he had a variety of friends, among them Charles Brockden Brown, the novelist, and George Frederick Cooke, the tragedian. He was the biographer for both of them, and these volumes are filled with anecdote, which throws light, not only on the subjects, but upon the observational taste of the writer. There are those who claim that he was unjust to Cooke, making him more of a drunkard than he really was. And the effect the book had on some of its readers may excellently well be seen by Lord Byron's exclamation, after having finished it. As quoted by Miss Crawford, in her "Romance of the American Theatre," he said: "Such a book! I believe, since 'Drunken Barnaby's Journal,' nothing like it has drenched the press. All green-room and tap-room, drams and the drama. Brandy, whiskey-punch, and, latterly, toddy, overflow every page. Two things are rather marvelous; first, that a man should live so long drunk, and next that he should have found a sober biographer."

Dunlap's first play was called "The Modest Soldier; or, Love in New York" (1787). We shall let him be his own chronicler:

As a medium of communication between the playwriter and the manager, a man was pointed out, who had for a time been of some consequence on the London boards, and now resided under another name in New York. This was the Dubellamy of the English stage, a first singer and walking-gentleman. He was now past his meridian, but still a handsome man, and was found sufficiently easy of access and full of the courtesy of the old school. A meeting was arranged at the City Tavern, and a bottle of Madeira discussed with the merits of this first-born of a would-be author. The wine was praised, and the play was praised – the first, perhaps, made the second tolerable – that must be good which can repay a man of the world for listening to an author who reads his own play.

In due course of time, the youthful playwright reached the presence of the then all-powerful actors, Hallam and Henry, and, after some conference with them, the play was accepted. But though accepted, it was not produced, that auspicious occasion being deferred whenever the subject was broached. At this time, young Dunlap was introduced to the stony paths of playwriting. He had to alter his manuscript in many ways, only to see it laid upon the shelf until some future occasion. And, according to his confession, the reason the piece did not receive immediate production was because there was no part which Henry, the six-foot, handsome idol of the day, could see himself in to his own satisfaction.

Dunlap's next play was "The Father; or, American Shandy-ism,"1 which was produced on September 7, 1789. It was published almost immediately, and was later reprinted, under the title of "The Father of an Only Child."

Most historians call attention to the fact that to Dunlap belongs the credit of having first introduced to the American stage the German dialect of the later Comedian. Even as we look to Tyler's "The Contrast" for the first Yankee, to Samuel Low's "Politician Out-witted" for an early example of Negro dialect, so may we trace other veins of American characteristics as they appeared in early American dramas.

But it is to "Darby's Return,"2 the musical piece, that our interest points, because it was produced for the benefit of Thomas Wignell, at the New-York Theatre (November 24, 1789), and probably boasted among its first-nighters George Washington. Writes Dunlap:

The eyes of the audience were frequently bent on his countenance, and to watch the emotions produced by any particular passage upon him was the simultaneous employment of all. When Wignell, as Darby, recounts what had befallen him in America, in New York, at the adoption of the Federal Constitution, and the inauguration of the President, the interest expressed by the audience in the looks and the changes of countenance of this great man became intense.

And then there follows an indication by Dunlap of where Washington smiled, and where he showed displeasure. And, altogether, there was much perturbation of mind over every quiver of his eye-lash. The fact of the matter is, as a playgoer, the Father of our Country figured quite as constantly as the Father of our Theatre. When the seat of Government changed from New York to Philadelphia, President Washington's love of the theatre prompted many theatrical enterprises to follow in his wake, and we have an interesting picture, painted in words by Seilhamer (ii, 316), of the scene at the old Southwark on such an occasion. He says:

[The President] frequently occupied the east stage-box, which was fitted up expressly for his reception. Over the front of the box was the United States coat-of-arms and the interior was gracefully festooned with red drapery. The front of the box and the seats were cushioned. According to John [sic] Durang, Washington's reception at the theatre was always exceedingly formal and ceremonious. A soldier was generally posted at each stage-door; four soldiers were placed in the gallery; a military guard attended. Mr. Wignell, in a full dress of black, with his hair elaborately powdered in the fashion of the time, and holding two wax candles in silver candle-sticks, was accustomed to receive the President at the box-door and conduct Washington and his party to their seats. Even the newspapers began to take notice of the President's contemplated visits to the theatre.

This is the atmosphere which must have attended the performance of Dunlap's "Darby's Return."

The play which probably is best known to-day, as by William Dunlap, is his "André,"3 in which Washington figures as the General, later to appear under his full name, when Dunlap utilized the old drama in a manuscript libretto, entitled "The Glory of Columbia – Her Yeomanry" (1817). The play was produced on March 30, 1798, after Dunlap had become manager of the New Park Theatre, within whose proscenium it was given. Professor Matthews, editing the piece for the Dunlap Society (No. 4, 1887), claims that this was the first drama acted in the United States during Washington's life, in which he was made to appear on the stage of a theatre. But it must not be forgotten that in "The Fall of British Tyranny," written in 1776, by Leacock, Washington appears for the first time in any piece of American fiction. Dunlap writes of the performance (American Theatre, ii, 20):

The receipts were 817 dollars, a temporary relief. The play was received with warm applause, until Mr. Cooper, in the character of a young American officer, who had been treated as a brother by André when a prisoner with the British, in his zeal and gratitude, having pleaded for the life of the spy in vain, tears the American cockade from his casque, and throws it from him. This was not, perhaps could not be, understood by a mixed assembly; they thought the country and its defenders insulted, and a hiss ensued – it was soon quieted, and the play ended with applause. But the feeling excited by the incident was propagated out of doors. Cooper's friends wished the play withdrawn, on his account, fearing for his popularity. However, the author made an alteration in the incident, and subsequently all went on to the end with applause.

A scene from the last act of "André"4 was produced at an American Drama Matinée, under the auspices of the American Drama Committee of the Drama League of America, New York Centre, on January 22nd and 23rd, 1917. There are many Arnold and André plays, some of which have been noted by Professor Matthews.5 Another interesting historical study is the stage popularity of Nathan Hale.

We might go on indefinitely, narrating incidents connected with Dunlap as citizen, painter, playwright, author, and theatrical manager, for within a very short time he managed the John Street and New Park Theatres, retiring for a while in 1805.

But this is sufficient to illustrate the pioneer character of his work and influence. Inaccurate he may have been in his "History of the American Theatre," but the atmosphere is there, and he never failed to recognize merit, and to give touches of character to the actors, without which our impression of the early theatre in this country would be the poorer. The name of William Dunlap is intimately associated with the beginnings of American painting, American literary life and the American Theatre. It is for these he will ever remain distinguished.

As a playwright, he wrote so rapidly, and so constantly utilized over and over again, not only his own material, but the materials of others, that it is not surprising to find him often in dispute with dramatic authors of the time. A typical disagreement occurred in the case of the actor John Hodgkinson (1767-1805), whose drama, "The Man of Fortitude; or, the Knight's Adventure," given at the John Street Theatre, on June 7, 1797, was, according to Dunlap, based on his own one-act verse play, "The Knight's Adventure," submitted to the actor some years before.

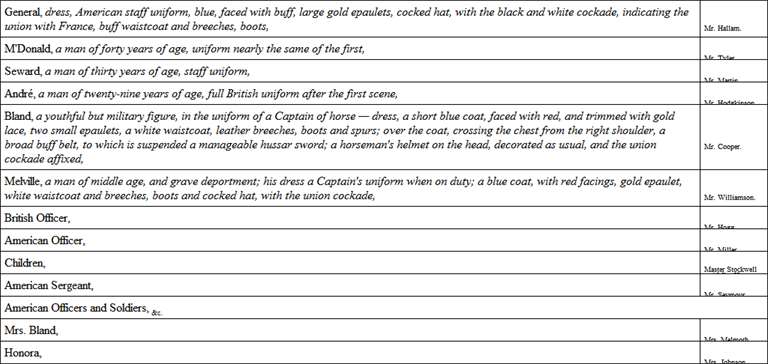

Only the play, based on the 1798 edition, is here reproduced. The authentic documents are omitted.

PREFACE

More than nine years ago the Author made choice of the death of Major André as the Subject of a Tragedy, and part of what is now offered to the public was written at that time. Many circumstances discouraged him from finishing his Play, and among them must be reckoned a prevailing opinion that recent events are unfit subjects for tragedy. These discouragements have at length all given way to his desire of bringing a story on the Stage so eminently fitted, in his opinion, to excite interest in the breasts of an American audience.

In exhibiting a stage representation of a real transaction, the particulars of which are fresh in the minds of many of the audience, an author has this peculiar difficulty to struggle with, that those who know the events expect to see them all recorded; and any deviation from what they remember to be fact, appears to them as a fault in the poet; they are disappointed, their expectations are not fulfilled, and the writer is more or less condemned, not considering the difference between the poet and the historian, or not knowing that what is intended to be exhibited is a free poetical picture, not an exact historical portrait.

Still further difficulties has the Tragedy of André to surmount, difficulties independent of its own demerits, in its way to public favour. The subject necessarily involves political questions; but the Author presumes that he owes no apology to any one for having shewn himself an American. The friends of Major André (and it appears that all who knew him were his friends) will look with a jealous eye on the Poem, whose principal incident is the sad catastrophe which his misconduct, in submitting to be an instrument in a transaction of treachery and deceit, justly brought upon him: but these friends have no cause of offence; the Author has adorned the poetical character of André with every virtue; he has made him his Hero; to do which, he was under the necessity of making him condemn his own conduct, in the one dreadfully unfortunate action of his life. To shew the effects which Major André's excellent qualities had upon the minds of men, the Author has drawn a generous and amiable youth, so blinded by his love for the accomplished Briton, as to consider his country, and the great commander of her armies, as in the commission of such horrid injustice, that he, in the anguish of his soul, disclaims the service. In this it appears, since the first representation, that the Author has gone near to offend the veterans of the American army who were present on the first night, and who not knowing the sequel of the action, felt much disposed to condemn him: but surely they must remember the diversity of opinion which agitated the minds of men at that time, on the question of the propriety of putting André to death; and when they add the circumstances of André's having saved the life of this youth, and gained his ardent friendship, they will be inclined to mingle with their disapprobation, a sentiment of pity, and excuse, perhaps commend the Poet, who has represented the action without sanctioning it by his approbation.

As a sequel to the affair of the cockade, the Author has added the following lines, which the reader is requested to insert, page 55, between the 5th and 15th lines, instead of the lines he will find there, which were printed before the piece was represented.6—

BlandNoble M'Donald, truth and honour's champion!Yet think not strange that my intemperance wrong'd thee:Good as thou art! for, would'st thou, canst thou, think it?My tongue, unbridled, hath the same offence,With action violent, and boisterous tone,Hurl'd on that glorious man, whose pious laboursShield from every ill his grateful country!That man, whom friends to adoration love,And enemies revere. – Yes, M'Donald,Even in the presence of the first of menDid I abjure the service of my country,And reft my helmet of that glorious badgeWhich graces even the brow of Washington.How shall I see him more! —M'DonaldAlive himself to every generous impulse,He hath excus'd the impetuous warmth of youth,In expectation that thy fiery soul,Chasten'd by time and reason, will receiveThe stamp indelible of godlike virtue.To me, in trust, he gave this badge disclaim'd,With power, when thou shouldst see thy wrongful error,From him, to reinstate it in thy helm,And thee in his high favour.[Gives the cockade.Bland [takes the cockade and replaces it]Shall I speak my thoughts of thee and him?No: – let my actions henceforth shew what thouAnd he have made me. Ne'er shall my helmetLack again its proudest, noblest ornament,Until my country knows the rest of peace,Or Bland the peace of death

ACT I

Scene I. A Wood seen by starlight; an Encampment at a distance appearing between the trees Enter MelvilleMelvilleThe solemn hour, "when night and morning meet,"Mysterious time, to superstition dear,And superstition's guides, now passes by;Deathlike in solitude. The sentinels,In drowsy tones, from post to post, send onThe signal of the passing hour. "All's well,"Sounds through the camp. Alas! all is not well;Else, why stand I, a man, the friend of man,At midnight's depth, deck'd in this murderous guise,The habiliment of death, the badge of dire,Necessitous coercion. 'T is not well.– In vain the enlighten'd friends of suffering manPoint out, of war, the folly, guilt, and madness.Still, age succeeds to age, and war to war;And man, the murderer, marshalls out his hostsIn all the gaiety of festive pomp,To spread around him death and desolation.How long! how long! —– Methinks I hear the tread of feet this way.My meditating mood may work me woe.[Draws.Stand, whoso'er thou art. Answer. Who's there? Enter BlandBlandA friend.MelvilleAdvance and give the countersign.BlandHudson.MelvilleWhat, Bland!BlandMelville, my friend, you here?MelvilleAnd well, my brave young friend. But why do you,At this dead hour of night, approach the camp,On foot, and thus alone?BlandI have but nowDismounted; and, from yon sequester'd cot,Whose lonely taper through the crannied wallSheds its faint beams, and twinkles midst the trees,Have I, adventurous, grop'd my darksome way.My servant, and my horses, spent with toil,There wait till morn.MelvilleWhy waited not yourself?BlandAnxious to know the truth of those reportsWhich, from the many mouths of busy Fame,Still, as I pass'd, struck varying on my ear,Each making th' other void. Nor does delayThe colour of my hasteful business suit.I bring dispatches for our great Commander;And hasted hither with design to waitHis rising, or awake him with the sun.MelvilleYou will not need the last, for the blest sunNe'er rises on his slumbers; by the dawnWe see him mounted gaily in the field,Or find him wrapt in meditation deep,Planning the welfare of our war-worn land.BlandProsper, kind heaven! and recompense his cares.MelvilleYou're from the South, if I presume aright?BlandI am; and, Melville, I am fraught with news?The South teems with events; convulsing ones:The Briton, there, plays at no mimic war;With gallant face he moves, and gallantly is met.Brave spirits, rous'd by glory, throng our camp;The hardy hunter, skill'd to fell the deer,Or start the sluggish bear from covert rude;And not a clown that comes, but from his youthIs trained to pour from far the leaden death,To climb the steep, to struggle with the stream,To labour firmly under scorching skies,And bear, unshrinking, winter's roughest blast.This, and that heaven-inspir'd enthusiasmWhich ever animates the patriot's breast,Shall far outweigh the lack of discipline.MelvilleJustice is ours; what shall prevail against her?BlandBut as I past along, many strange tales,And monstrous rumours, have my ears assail'd:That Arnold had prov'd false; but he was ta'en,And hung, or to be hung – I know not what.Another told, that all our army, with theirMuch lov'd Chief, sold and betray'd, were captur'd.But, as I nearer drew, at yonder cot,'T was said, that Arnold, traitor like, had fled;And that a Briton, tried and prov'd a spy,Was, on this day, as such, to suffer death.MelvilleAs you drew near, plain truth advanced to meet you.'T is even as you heard, my brave young friend.Never had people on a single throwMore interest at stake; when he, who heldFor us the die, prov'd false, and play'd us foul.But for a circumstance of that nice kind,Of cause so microscopic, that the tonguesOf inattentive men call it the effectOf chance, we must have lost the glorious game.BlandBlest, blest be heaven! whatever was the cause!MelvilleThe blow ere this had fallen that would have bruis'dThe tender plant which we have striven to rear,Crush'd to the dust, no more to bless this soil.BlandWhat warded off the blow?MelvilleThe brave young man, who this day dies, was seiz'dWithin our bounds, in rustic garb disguis'd.He offer'd bribes to tempt the band that seiz'd him;But the rough farmer, for his country arm'd,That soil defending which his ploughshare turn'd,Those laws, his father chose, and he approv'd,Cannot, as mercenary soldiers may,Be brib'd to sell the public-weal for gold.Bland'T is well. Just heaven! O, grant that thus may fallAll those who seek to bring this land to woe!All those, who, or by open force, or darkAnd secret machinations, seek to shakeThe Tree of Liberty, or stop its growth,In any soil where thou hast pleas'd to plant it.MelvilleYet not a heart but pities and would save him;For all confirm that he is brave and virtuous;Known, but till now, the darling child of Honour.Bland [contemptuously]And how is call'd this – honourable spy?MelvilleAndré's his name.Bland [much agitated]André!MelvilleAye, Major André.BlandAndré! Oh no, my friend, you're sure deceiv'd —I'll pawn my life, my ever sacred fame,My General's favour, or a soldier's honour,That gallant André never yet put onThe guise of falsehood. Oh, it cannot be!MelvilleHow might I be deceiv'd? I've heard him, seen him,And what I tell, I tell from well-prov'd knowledge;No second tale-bearer, who heard the news.BlandPardon me, Melville. Oh, that well-known name,So link'd with circumstances infamous! —My friend must pardon me. Thou wilt not blameWhen I shall tell what cause I have to love him:What cause to think him nothing more the pupilOf Honour stern, than sweet Humanity.Rememberest thou, when cover'd o'er with wounds,And left upon the field, I fell the preyOf Britain? To a loathsome prison-shipConfin'd, soon had I sunk, victim of death,A death of aggravated miseries;But, by benevolence urg'd, this best of men,This gallant youth, then favour'd, high in power,Sought out the pit obscene of foul disease,Where I, and many a suffering soldier lay,And, like an angel, seeking good for man,Restor'd us light, and partial liberty.Me he mark'd out his own. He nurst and cur'd,He lov'd and made his friend. I liv'd by him,And in my heart he liv'd, till, when exchang'd,Duty and honour call'd me from my friend. —Judge how my heart is tortur'd. – Gracious heaven!Thus, thus to meet him on the brink of death —A death so infamous! Heav'n grant my prayer.[Kneels.That I may save him, O, inspire my heartWith thoughts, my tongue with words that move to pity![Rises.Quick, Melville, shew me where my André lies.MelvilleGood wishes go with you.BlandI'll save my friend.[Exeunt.Scene, the Encampment, by starlight Enter the General, M'Donald and SewardGeneral'T is well. Each sentinel upon his postStands firm, and meets me at the bayonet's point;While in his tent the weary soldier lies,The sweet reward of wholesome toil enjoying;Resting secure as erst within his cotHe careless slept, his rural labour o'er;Ere Britons dar'd to violate those laws,Those boasted laws by which themselves are govern'd,And strove to make their fellow-subjects slaves.SewardThey know to whom they owe their present safety.GeneralI hope they know that to themselves they owe it:To that good discipline which they observe,The discipline of men to order train'd,Who know its value, and in whom 't is virtue:To that prompt hardihood with which they meetOr toil or danger, poverty or death.Mankind who know not whence that spirit springs,Which holds at bay all Britain's boasted power,Gaze on their deeds astonish'd. See the youthStart from his plough, and straightway play the hero;Unmurmuring bear such toils as veterans shun;Rest all content upon the dampsome earth;Follow undaunted to the deathful charge;Or, when occasion asks, lead to the breach,Fearless of all the unusual din of war,His former peaceful mates. O patriotism!Thou wond'rous principle of god-like action!Wherever liberty is found, there reignsThe love of country. Now the self-same spiritWhich fill'd the breast of great Leonidas,Swells in the hearts of thousands on these plains,Thousands who never heard the hero's tale.'T is this alone which saves thee, O my country!And, till that spirit flies these western shores,No power on earth shall crush thee!Seward'T is wond'rous!The men of other climes from this shall seeHow easy 't is to shake oppression off;How all resistless is an union'd people:And hence, from our success (which, by my soul,I feel as much secur'd, as though our foesWere now within their floating prisons hous'd,And their proud prows all pointing to the east),Shall other nations break their galling fetters,And re-assume the dignity of man.M'DonaldAre other nations in that happy state,That, having broke Coercion's iron yoke,They can submit to Order's gentle voice,And walk on earth self-ruled? I much do fear it.As to ourselves, in truth, I nothing see,In all the wond'rous deeds which we perform,But plain effects from causes full as plain.Rises not man for ever 'gainst oppression?It is the law of life; he can't avoid it.But when the love of property unitesWith sense of injuries past, and dread of future.Is it then wonderful, that he should braveA lesser evil to avoid a greater?General [sportively]'T is hard, quite hard, we may not please ourselves,By our great deeds ascribing to our virtue.SewardM'Donald never spares to lash our pride.M'DonaldIn truth I know of nought to make you proud.I think there's none within the camp that drawsWith better will his sword than does M'Donald.I have a home to guard. My son is – butcher'd —SewardHast thou no nobler motives for thy armsThan love of property and thirst of vengeance?M'DonaldYes, my good Seward, and yet nothing wond'rous.I love this country for the sake of man.My parents, and I thank them, cross'd the seas,And made me native of fair Nature's world,With room to grow and thrive in. I have thriven;And feel my mind unshackled, free, expanding,Grasping, with ken unbounded, mighty thoughts,At which, if chance my mother had, good dame,In Scotia, our revered parent soil,Given me to see the day, I should have shrunkAffrighted. Now, I see in this new worldA resting spot for man, if he can standFirm in his place, while Europe howls around him,And all unsettled as the thoughts of vice,Each nation in its turn threats him with feeble malice.One trial, now, we prove; and I have met it.GeneralAnd met it like a man, my brave M'Donald.M'DonaldI hope so; and I hope my every actHas been the offspring of deliberate judgment;Yet, feeling second's reason's cool resolves.Oh! I could hate, if I did not more pity,These bands of mercenary Europeans,So wanting in the common sense of nature,As, without shame, to sell themselves for pelf,To aid the cause of darkness, murder man —Without inquiry murder, and yet callTheir trade the trade of honour – high-soul'd honour —Yet honour shall accord in act with falsehood.Oh, that proud man should e'er descend to playThe tempter's part, and lure men to their ruin!Deceit and honour badly pair together.SewardYou have much shew of reason; yet, methinksWhat you suggest of one, whom fickle Fortune,In her changeling mood, hath hurl'd, unpitying,From her topmost height to lowest misery,Tastes not of charity. André, I mean.M'DonaldI mean him, too; sunk by misdeed, not fortune.Fortune and chance, Oh, most convenient words!Man runs the wild career of blind ambition,Plunges in vice, takes falsehood for his buoy,And when he feels the waves of ruin o'er him,Curses, in "good set terms," poor Lady Fortune.General [sportively to Seward]His mood is all untoward; let us leave him.Tho' he may think that he is bound to rail,We are not bound to hear him.[To M'Donald.Grant you that?M'DonaldOh, freely, freely! you I never rail on.GeneralNo thanks for that; you've courtesy for office.M'DonaldYou slander me.GeneralSlander that would not wound.Worthy M'Donald, though it suits full wellThe virtuous man to frown on all misdeeds;Yet ever keep in mind that man is frail;His tide of passion struggling still with Reason'sFair and favourable gale, and adverseDriving his unstable Bark upon theRocks of error. Should he sink thus shipwreck'd,Sure it is not Virtue's voice that triumphsIn his ruin. I must seek rest. Adieu