полная версия

полная версияThe White Prophet, Volume II (of 2)

"Master," said one of the Sheikhs, "I have eaten bread and salt with you, therefore I will not deceive you. Let Omar go first. He can do all that Ishmael can do and run no risk."

"Messenger of the Merciful," said another, "neither will I deceive you. Omar knows Cairo best. Therefore let him go first."

After others had answered in the same way Ishmael turned to Mahmud, his uncle, whereupon the old man wiped his rheumy eyes and said —

"Your life is in God's hand, O son of my brother, and man cannot escape his destiny. If it is God's will that you should be the first to go into Cairo you will go, and God will protect you. But speaking for myself, I should think it a shame and a humiliation that the father of his people should not enter the city with his children. If Omar says he can do as much as you, believe him – the white man does not lie."

No sooner had the old man concluded than the whole company with one voice shouted that they were all of the same opinion, whereupon Ishmael cried —

"So be it, then! Omar it shall be! And do not think for one moment that I grudge your choice."

"El Hamdullillah!" shouted the company, as from a sense of otherwise inexpressible relief.

Meantime Gordon was conscious only of Helena's violent agitation. Though he dared not look at her, he seemed to see her feverish face and the expression of terror in her lustrous eyes. At length, when the shouts of the Sheikhs had subsided, he heard her tremulous voice saying hurriedly to Ishmael —

"Do not listen to them."

"But why, my Rani?" Ishmael asked in a whisper.

She tried to answer him and could not. "Because … because – "

"Because – what?" asked Ishmael again.

"Oh, I don't know – I can't think – but I beg you, I entreat you not to let Omar go into Cairo."

Her agitated voice caused another moment of silence, and then Ishmael said in a soft, indulgent tone —

"I understand you, O my Rani. This may be the task of greatest danger, but it is the place of highest honour too, and you would fain see no man except your husband assigned to it. But Omar is of me and I am of him, and there can be no pride nor jealousy between us."

And then, taking Gordon by the right hand, while with his left he was holding Helena, he said —

"Omar, my friend, my brother!"

"El Hamdullillah!" cried the Sheikhs again, and then one by one they rose to go.

Helena rose too, and with her face aflame and her breath coming in gusts she hurried back to her room. The Arab woman followed her in a moment, and with a mocking smile in her glinting eyes, she said —

"How happy you must be, O lady, that some one else than your husband is to go into that place of danger!"

But Helena could bear no more.

"Go out of the room this moment! I cannot endure you! I hate you! Go, woman, go!" she cried.

Zenoba fled before the fury in her lady's face, but at the next moment Helena had dropped to the floor and burst into a flood of tears.

When she regained possession of herself, the child, Ayesha, was embracing her and, without knowing why, was weeping over her wet cheeks.

CHAPTER XXI

Now that Gordon was to take Ishmael's place, Helena found herself deeper than ever in the toils of her own plot. She could see nothing but death before him as the result of his return to Cairo. If his identity were discovered, he would die for his own offences as a soldier. If it were not discovered, he would be executed for Ishmael's conspiracies as she had made them known.

"Oh, it cannot be! It must not be! It shall not be!" she continued to say to herself, but without seeing a way to prevent it.

Never for a moment, in her anxiety to save Gordon from stepping into the pit she had dug for Ishmael, did she allow herself to think that, being the real cause of her father's death, he deserved the penalty she had prepared for the guilty man. Her mind had altered towards that event since the man concerned in it had changed. The more she thought of it the more sure she became that it was a totally different thing, and in the strict sense hardly a crime at all.

In the first place, she reminded herself that her father had suffered from an affection of the heart which must have contributed to his death, even if it had not been the principal cause of it. How could she have forgotten that fact until now?

Remembering her father's excitement and exhaustion when she saw him last, she could see for the first time, by the light of Gordon's story, what had afterwards occurred – the burst of ungovernable passion, the struggle, the fall, the death.

Then she told herself that Gordon had not intended to kill her father, and whatever he had done had been for love of her. "Helena was mine, and you have taken her from me, and broken her heart as well as my own." Yes, love for her and the torment of losing her had brought Gordon back to the Citadel after he had been ordered to return to his quarters. Love for her, and the delirium of a broken heart, had wrung out of him the insults which had led to the quarrel that resulted in her father's death.

In spite of her lingering tenderness for the memory of her father, she began to see how much he had been to blame for what had happened – to think of the gross indignity, the frightful shame, the unmerciful and even unlawful degradation to which in his towering rage he had subjected Gordon. The scene came back to her with horrible distinctness now – her father crying in a half-stifled voice, "You are a traitor! A traitor who has consorted with the enemies of his country!" and then tearing Gordon's sword from its scabbard and breaking it across his knee.

But seeing this, she also saw her own share in what had occurred. At the moment of Gordon's deepest humiliation she had driven him away from her. Her pride had conquered her love, and instead of flinging herself into his arms as she ought to have done, whether he was in the right or in the wrong, when everybody else was trampling upon him, she had insulted him with reproaches and turned her back upon him in his disgrace.

That scene came back to her, too – Gordon at the door of the General's house, with his deadly white face and trembling lips, stammering out, "I couldn't help it, Helena – it was impossible for me to act otherwise," and then, bareheaded as he was, and with every badge of rank and honour gone, staggering across the garden to the gate.

When she thought of all this now it seemed to her that, if anybody had been to blame for her father's death, it was not Gordon, but herself. His had been the hand, the blind hand only, but the heart that had wrought the evil had been hers.

"Oh, it cannot be! it shall not be!" she continued to say to herself, and just as she had tried to undo her work with Ishmael when he was bent on going into Cairo, so she determined to do the same with Gordon, now that he had stepped into Ishmael's place. Her opportunity came soon.

A little before mid-day of the day following the meeting of the Sheikhs, she was alone in the guest-room, sitting at the brass table that served her as a desk – Ishmael being in the camp, Zenoba and the child in the town, and old Mahmud still in bed – when Gordon came out of the men's quarter and walked towards the door as if intending to pass out of the house.

He had seen her as he came from his bedroom, with one of her hands pressed to her brow, and a feeling of inexpressible pity and unutterable longing had so taken possession of him, with the thought that he was soon to lose her – the most precious gift life had given him – that he had tried to steal away.

But instinctively she felt his approach, and with a trembling voice she called to him, so he returned and stood by her side.

"Why are you doing this?" she said. "You know what I mean. Why are you doing it?"

"You know quite well why I am doing it, Helena. Ishmael was determined to go to his death. There was only one way to prevent him. I had to take it."

"But you are going to death yourself – isn't that so?"

He did not answer. He was trying not to look at her.

"Or perhaps you see some way of escape – do you?"

Still he did not speak – he was even trying not to hear her.

"If not, why are you going into Cairo instead of Ishmael?"

"Don't ask me that, Helena. I would rather not answer you."

Suddenly the tears came into her eyes, and after a moment's silence she said —

"I know! I understand! But remember your father. He loves you. You may not think it, but he does – I am sure he does. Yet if you go into Cairo you know quite well what he will do."

"My father is a great man, Helena. He will do his duty whatever happens – what he believes to be his duty."

"Certainly he will, but all the same, do you think he will not suffer! And do you wish to put him into the position of being compelled to cut off his own son? Is that right? Can anything – anything in the world – make it necessary?"

Gordon did not answer her, but under the strain of his emotion he tightened his lips, and his pinched nostrils began to dilate like the nostrils of a horse.

"Then remember your mother, too," said Helena. "She is weak and ill. It breaks my heart to think of her as I saw her last. She believes that you have fled away to some foreign country, but she is living in the hope that time will justify you, and then you will be reconciled to your father, and come back to her again. Is this how you would come back? … Oh, it will kill her! I'm sure it will!"

She saw that Gordon's strong and manly face was now utterly discomposed, and she could not help but follow up her advantage.

"Then think a little of me too, Gordon. This is all my fault, and if anything is done to you in Cairo it will be just the same to me as if I had done it. Do you wish me to die of remorse?"

She saw that he was struggling to restrain himself, and turning her beautiful wet eyes upon him and laying her hand on his arm, she said —

"Don't go back to Cairo, Gordon! For my sake, for your own sake, for our love's sake – "

But Gordon could bear no more, and he cried in a low, hoarse whisper —

"Helena, for heaven's sake, don't speak so. I knew it wouldn't be easy to do what I intended to do, and it isn't easy. But don't make it harder for me than it is, I beg, I pray."

She tried to speak again, but he would not listen.

"When you sent the message into Cairo which doomed Ishmael to death you thought he had killed your father. If he had really done so he would have deserved all you did to him. But he hadn't, whereas I had. Do you think I can let an innocent man die for my crime?"

"But, Gordon – " she began, and again he stopped her.

"Don't speak about it, Helena. For heaven's sake, don't! I've fought this battle with myself before, and I can't fight it over again – with your eyes upon me too, your voice in my ears, and your presence by my side."

He was trying to move away, and she was still clinging to his arm.

"Don't speak about our love, either. All that is over now. You must know it is. There is a barrier between us that can never – "

His voice was breaking and he was struggling to tear himself away from her, but she leapt to her feet and cried —

"Gordon, you shall hear me – you must!" and then he stopped short and looked at her.

"You think you were the cause of my father's death, but you were not," she said.

His mouth opened, his lips trembled, he grew deadly pale.

"You think, too, that there is a barrier of blood between us, but there is no such thing."

"Take care of what you are saying, Helena."

"What I am saying is the truth, Gordon – it is God's truth."

He looked blankly at her for a moment in silence, then laid hold of her violently by both arms, gazed closely into her face, and said in a low, trembling voice —

"Helena, if you knew what it is to live for months under the shadow of a sin – an awful sin – an unpardonable sin – surely you wouldn't … But why don't you speak? Speak, girl, speak!"

Then Helena looked fearlessly back into his excited face and said —

"Gordon, do you remember that you came to my room in the Citadel before you went in to that … that fatal interview?"

"Yes, yes! How can I forget it?"

"Do you also remember what I told you then, that whatever happened that day I could never leave my father?"

"Yes, certainly, yes."

"Do you remember that you asked me why, and I said I couldn't tell you because it was a secret – somebody else's secret?"

"Well?" His pulses were beating violently; she could feel them throbbing on her arms.

"Gordon," she said, "do you know what that secret was? I can tell you now. Do you know what it was?"

"What?"

"That my father was suffering from heart-disease, and had already received his death-warrant."

She waited for Gordon to speak, but he was almost afraid to breathe.

"He didn't know his condition until we arrived in Egypt, and then perhaps he ought to have resigned his commission, but he had been out of the service for two years, and the temptation to remain was too much for him, so he asked me to promise to say nothing about it."

Gordon released her arms and she sat down again. He stood over her, breathing fast and painfully.

"I thought you ought to have been told at the time when we became engaged, but my father said, 'No! Why put him in a false position, and burden him with responsibilities he ought not to bear?'"

Helena's own voice was breaking now, and as Gordon listened to it he was looking down at her flushed face, which was thinner than before but more beautiful than ever in his eyes, and a hundredfold more touching than when it first won his heart.

"I tried to tell you that day, too, before you went into the General's office, so that you might see for yourself, dear, that if you separated yourself from my father I … I couldn't possibly follow you, but there was my promise, and then … then my pride and … and something you said that pained and wounded me – "

"I know, I know, I know," he said.

"But now," she continued, rising to her feet again, "now," she repeated, in the same trembling voice, but with a look of joy and triumph, "now that you have told me what happened after your return to the Citadel, I see quite clearly – I am sure – perfectly sure – that my dear father died not by your hand at all, but by the hand and the will of God."

"Helena! Helena!" cried Gordon, and in the tempest of his love and the overwhelming sense of boundless relief he flung his arms about her and covered her face with kisses.

One long moment of immeasurable joy they were permitted to know, and then the hand of fate snatched at them again.

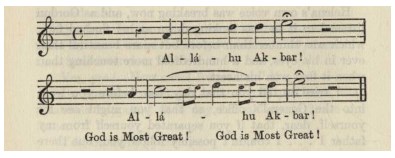

From their intoxicating happiness they were awakened by a voice. It was only the voice of the muezzin calling to mid-day prayers, but it seemed to be reproaching them, separating them, tearing them asunder, reminding them of where they were now, and what they were, and that God was over them.

Music fragment

Their lips parted, their arms fell away from each other, and irresistibly, simultaneously, as if by an impulse of the same heart, they dropped to their knees to pray for pardon.

The voice of the muezzin ceased, and in the silence of the following moment they heard a soft footstep coming behind.

It was Ishmael. He did not speak to either of them, but seeing them on their knees, at the hour of mid-day prayers, he stepped up and knelt between.

CHAPTER XXII

When Gordon had time to examine the new situation in which he found himself he saw that he was now in a worse case than before.

It had been an inexpressible relief to realise that he was not the first cause of the General's death, and therefore that conscience did not require him to go into Cairo in order to protect Ishmael from the consequences of a crime he did not commit. But no sooner had he passed this great crisis than he was brought up against a great test. What was it to him that he could save his life if he had to lose Helena?

Helena was now Ishmael's wife – betrothed to him by the most sacred pledges of Mohammedan law. If the barrier of blood which had kept him from Helena had been removed, the barrier of marriage which kept Helena from him remained.

"What can we do?" he asked himself, and for a long time he saw no answer.

In the fierce struggle that followed, honour and duty seemed to say, that inasmuch as Helena had entered into this union of her own free will – however passively acquiescing in its strange conditions – she must abide by it, and he must leave her where she was and crush down his consuming passion, which was an unholy passion now. But honour and duty are halting and timorous guides in the presence of love, and when Gordon came to think of Helena as the actual wife of Ishmael he was conscious of nothing but the flame that was burning at his heart's core.

Remembering what Helena had told him, and what he had seen since he came to that house, he reminded himself that after all the marriage was only a marriage pro formâ, a promise made under the mysterious compulsion of fate, a contract of convenience and perhaps generosity on the one side, and on the other side of dark and calculating designs which would not bear to be thought of any longer, being a result of the blind leading of awful passions under circumstances of the most irresistible provocation.

When he came to think of love he was dead to everything else. Ishmael did not love Helena, whereas he, Gordon, loved her with all his heart and soul and strength. She was everything in life to him, and though he might have gone to his death without her, it was impossible to live and leave her behind him.

Thinking so, he began to conjure up the picture of a time when Ishmael, under the influence of Helena's beauty and charm, might perhaps forget the bargain between them, and claim his rights as a husband, and then the thought of her beautiful head with its dark curling locks as it lay in his arms that day lying in the arms of the Arab, with Ishmael's swarthy face above her, so tortured him that it swept away every other consideration.

"It must not, shall not, cannot be!" he told himself.

And that brought him to the final thought that since he loved Helena, and since Helena loved him and not her husband, their position in Ishmael's house was utterly false and wrong, and could not possibly continue.

"It is not fair even to Ishmael himself," he thought.

And when, struggling with his conscience, he asked himself how he was to put an end to the odious and miserable situation, he concluded at once that he would go boldly to Ishmael and tell him the whole story of Helena's error and temptation, thereby securing his sympathy and extricating all of them from the position in which they were placed.

"Anything will be better than the present state of things," he thought, as he reflected upon the difficult and delicate task he intended to undertake.

But after a moment he saw that while it would be hard to explain Helena's impulse of vengeance to the man who had been the object of it, to tell him of the message she had sent into Cairo would be utterly impossible.

"I cannot say anything to Ishmael about that," he thought, and the only logical sequence of ideas was that he could not say anything to Ishmael at all.

This left him with only one conclusion – that inasmuch as it was impossible that he and Helena could remain any longer in that house, and equally impossible that they could leave it with Ishmael's knowledge and consent, there was nothing for them to do but to fly away.

He found it hard to reconcile himself to the idea of a secret flight. The very thought of it seemed to put them into the position of adulterers, deceiving an unsuspecting husband. But when he remembered the scene in the guest-room that day, the moment of over-powering love, the irresistible kiss, and then the crushing sense of duplicity, as Ishmael entered and without a thought of treachery knelt between them, he told himself that at any cost whatsoever he must put an end to the false position in which they lived.

"We must do it soon – the sooner the better," he thought.

Though he had lived so long with the thought of losing Helena, that kiss had in a moment put his soul and body into a flame. He knew that his love was blinding him to certain serious considerations, and that some of these would rise up later and perhaps accuse him of selfishness or disloyalty or worse. But he could only think of Helena now, and his longing to possess her made him dead to everything else.

In a fever of excitement he began to think out plans for their escape, and reflecting that two days had still to pass before the train left Khartoum by which it had been intended that he should travel in his character as Ishmael's messenger, he decided that it was impossible for them to wait for that.

They must get away at once by camel if not by rail. And remembering Osman, his former guide and companion, he concluded to go over to the Gordon College and secure his aid.

Having reached this point, he asked himself if he ought not to obtain Helena's consent before going any further; but no, he would not wait even for that. And then, remembering how utterly crushed she was, a victim of storm and tempest, a bird with a broken wing, he assumed the attitude of strength towards her, telling himself she was a woman after all, and it was his duty as a man to think and to act for her.

So he set out in haste to see Osman, and when, on his way through the town, he passed (without being recognised) a former comrade in khaki, a Colonel of Lancers, whose life had been darkened by the loss of his wife through the treachery of a brother officer, he felt no qualms at all at the thought of taking Helena from Ishmael.

"Ours is a different case altogether," he said, and then he told himself that their life would be all the brighter in the future because it had had this terrible event in it.

It was late and dark when he returned from the Gordon College, and then old Mahmud's house was as busy as a fair, with people coming and going on errands relating to the impending pilgrimage, but he watched his opportunity to speak to Helena, and as soon as Ishmael, who was more than commonly animated and excited that night, had dismissed his followers and gone to the door to drive them home, he approached her and whispered in her ear —

"Helena!"

"Yes?"

"Can you be ready to leave Khartoum at four o'clock in the morning?"

For a moment she made no reply. It seemed to her an incredible happiness that they were really to go away together. But quickly collecting her wandering thoughts she answered —

"Yes, I can be ready."

"Then go down to the Post Landing. I shall be there with a launch."

"Yes, yes!" Her heart was beating furiously.

"Osman, the guide who brought me here, will be waiting with camels on the other side of the river."

"Yes, yes, yes!"

"We are to ride as far as Atbara, and take train from there to the Red Sea."

"And what then?"

"God knows what then. We must wait for the direction of fate. America, perhaps, as we always hoped and intended."

She looked quickly round, then took his face between her hands and kissed him.

"To-morrow morning at four o'clock," she whispered.

"At four," he repeated.

A thousand thoughts were flashing through her mind, but she asked no further questions, and at the next moment she went off to her own quarters.

The door of her room was ajar, and the face of the Arab woman, who was within, doing something with the clothes of the child, seemed to wear the same mocking smile as before; but Helena was neither angry nor alarmed. When she asked herself if the woman had seen or heard what had taken place between Gordon and herself, no dangers loomed before her in relation to their flight.

Her confidence in Gordon – his strength, his courage, his power to protect her – was absolute. If he intended to take her away he would do so, and not Ishmael nor all the Arabs on earth could stop him.

CHAPTER XXIII

Gordon could not allow himself to sleep that night, lest he should not be awake when the hour came to go. The room he shared with Ishmael was large, and it had one window looking to the river and another to Khartoum. Through these windows, which were open, he heard every noise of the desert town by night.