полная версия

полная версияThe White Prophet, Volume II (of 2)

Beginning in a low, tired voice, that would barely have reached the limits of the mosque but for the breathlessness of the people, he said that God had brought them to a new stage in the progress of humanity. Islam was rising out of the corruption of ages. Egypt was having a new birth of freedom. God had whitened their faces before the world, and in His wisdom He had willed it that the oldest of the nations should not perish from the earth.

"Ameen! Ameen!" replied a hundred vehement voices, whereupon Ishmael rose from his seat and raised his arm.

It was an hour of glory, but let them not be vainglorious. Let them not think that with their puny hands they had won these triumphs. Allah alone did all.

"Beware of boasting," he cried, "it is the strong drink of ignorance. Beware of them that would tell you that by any act of yours you have humbled the pride or lowered the strength of the great nation under whose arm we live. Only God has changed its heart. He has given it to see that the true welfare of a people is moral, not material. And now, steadily, calmly, out of the spirit that has always inspired its laws, its traditions and its faith, it shows us mercy and justice."

"Ameen! Ameen!" came again, but less vehemently than before.

Then speaking of Gordon without naming him, Ishmael reminded his people that some of the great nation's own sons had helped them.

"One there is who has been our warmest friend," he cried. "To him, the pure of heart, the high of soul, although he is a soldier and a great one, may Peace herself award the crown of life! Christian he may be, but may God place His benediction upon him to all eternity! May the God of the East bless him! May the God of the West bless him! May his name be inscribed with blessings from the Koran on the walls of every mosque!"

This reference, plainly understood by all, was received with loud and ringing shouts of "Allah! Allah!"

Then Ishmael's sermon took a new direction. For thirteen centuries the children of men, forgetting their prophets, Mohammed and Jesus and Moses, had been given over to idolatry. They had worshipped a god of their own fashioning. That god was gold. Its temples were great cities given up to material pursuits, and under them were the dead souls of millions of human beings. Its altars were vast armies which spilled the rivers of blood which had to be sacrificed to its lust. As men had become rich they had become barbarous, as nations had become great they had become pagan. Islam and Christianity alike had had to fight against some of the powers of darkness which called themselves civilisation and progress. But a new era had begun, and the human heart was raising its face to God.

"Once again a voice has gone out from Mecca, from Nazareth, from Jerusalem, saying, 'There is no god but God.' Once again a voice has gone out from the desert, crying, 'Thou shalt have no other god but Me!'"

At this the people were carried out of themselves with excitement, and loud shouts again rang through the mosque.

Then Ishmael spoke of the future. The world had been in labour, in the throes of a new birth, but the end was not yet. Had he promised them that the Kingdom of Heaven would come when they entered Cairo? Let him bend his knee in humility and ask pardon of the Merciful. Had he said the Redeemer would appear? Let him fall on his face before God. Not yet! Not yet!

"But," he cried, leaning out of the pulpit, with a look of inspiration in his upturned eyes, "I see a time coming when the worship of wealth will cease, when the governments of the nations will realise that man does not live by bread alone; when the children of men will see that the things of the spirit are the only true realities, worth more than much gold and many diamonds, and not to be bartered away for the shows of life; when the scourge of war will pass away; when, divisions of faith will be no more known; when all men, whether black or white, will be brothers, and in the larger destiny of the human race the world will be One.

"That time is near, O brothers," cried Ishmael, "and many who are with us to-day will live to witness it."

"You, Master, you!" cried a voice from below, whereupon Ishmael paused for a perceptible moment, and then said, in a sadder voice —

"No; with the eyes of the body I shall not see that time."

Loud shouts of affectionate protest came from the people.

"God forbid it!" they cried.

"God has forbidden it," said Ishmael. "I pass out of your lives from this day forward. Our paths part. You will see me no more."

Again came loud shouts of protest – not unusual in a mosque – with voices calling on Ishmael to remain and lead the people.

"My work here is done," he answered. "The little that God gave me to do is finished. And now He calls me away."

"No, no!" cried the people.

"Yes, yes," replied Ishmael; and then in simple, touching words he told them the story of the Prophet Moses – how, by reason of his sin, he was forbidden to enter the Promised Land.

"Many of us have our promised land which we may never enter," he said. "This is mine, and here I may not stay."

The protests of the people ceased; they listened without breathing.

"Yet Moses was taken up into a high mountain, and from there he saw what lay before his people; and from a high mountain of my soul I see the Promised Land which lies before you. But to me a voice has come which says, 'Enter thou not!'"

The people were now deeply moved.

"We are all sinners," Ishmael continued.

"Not thou, O Master," cried several voices at once.

"Yes, I more than any other, for I have sinned against you and against the Merciful."

Then, raising his arms as if in blessing, he cried —

"O slaves of God, be brothers one to another! If you think of me when I am gone, think of me as of one who saw the coming of the Kingdom of Heaven on earth as plainly as his eyes behold you now. If I leave you I leave this hope, this comforter, behind me. Think that Azrael, the angel of death, has spread his wings over the desert track that hides me from your eyes. And pray for me – pray for me with the sinner's prayer, the sinner's cry."

Then, in deep, tremulous tones which seemed to be the inner voice of the whole of his being, he cried —

"O Thou who knowest every heart and hearest every cry, look down and hearken to me now! One sole plea I make – my need of Thee! One only hope I have – to stand at Thy mercy-gate and knock! Penitent, I kneel at Thy feet! Suppliant, I stretch forth my hands! Save me, O God, from every ill!"

The words of the prayer were familiar to everybody in the mosque, but so deep was their effect as Ishmael repeated them in his trembling, throbbing voice, that it seemed as if nobody present had ever heard them before.

The emotion of the people wras now very great. "Allah! Allah! Allah!" they cried, and they prostrated themselves with their faces to the floor.

When the cold, slow, sonorous voice of the Reader began again, and the vast congregation raised their heads, the pulpit was empty and Ishmael was gone.

CHAPTER XX

Meantime the General's house on the edge of the ramparts was being made ready for its new tenant. Fatimah, Ibrahim and Mosie, with a small army of Arab servants, had been there since early morning, washing, dusting, and altering the position of furniture. Towards noon the Princess had arrived in her carriage, which, with her customary retinue of gorgeously apparelled black attendants, was now standing by the garden gate. Helena had come with her, but for the first time in her life she was utterly weak and helpless. Just as a nervous collapse may follow upon nervous strain so a collapse of character may come after prolonged exercise of will. Something of this kind was happening to Helena, who stood by the window in the General's office, looking down at the city and running her fingers along the hem of her handkerchief, while the Princess, bustling about, laughed at her and rallied her.

"Goodness me, girl, you used to have some blood in your veins, but now —Mon Dieu! To think of you who went down there, and did that, and used to drive a motor-car through the traffic as calmly as if it had been a go-cart, trembling and jerking as if you had got the jumps!"

Meantime the Princess herself, full of energy, was ordering the servants about, and, by a hundred little changes, was giving to the General's office a look that almost obliterated its former appearance.

"We'll have the desk here and the sofa there … what do you say to the sofa there, my sweet?"

"Hadn't you better ask Gordon himself, Princess?" asked Helena.

"But the man isn't here, and how can I… Never mind, leave them where they are, Ibrahim. And now for the pictures – nothing makes a room look so fresh as a lot of pictures."

Ibrahim had brought up from the Agency a number of pictures which had belonged to Gordon's mother, and the Princess, using her lorgnette, proceeded to examine them.

"What's this? 'Charles George Gordon.' I know! The White Pasha. Put him over the General's desk. 'Ecce Homo.' Humph! A man couldn't wish to have a thing like this in his office, and a natural woman can't want it over her bed. Mosie! Take 'Ecce Homo' to a nice dark corner of the servants' hall."

At that moment Fatimah came from the kitchen, which had been shut up since the day after Helena's departure for the Soudan, to say that half the cooking-tins had disappeared.

"Just what I expected! Stolen by those rascally Egyptian cooks, no doubt. Rascally Egyptians! That's what I call them. Excuse the word, my dear. I speak my mind. They'd steal the kohl from your eyes – if you had any. And these are the people who are to govern the country! But I say nothing – not I, indeed! The virtue of a woman is in holding her tongue… Fatimah, now that you are here, you might make yourself useful. Dust that big picture of the naked babies. What's it called? 'Suffer little children.' Goodness! He looks as if he were giving away clothes. Helena, my moon, my beauty, you really must tell me where to put this one."

"But hadn't you better ask Gordon himself, Princess? It's to be his house, you know," repeated Helena, whereupon the Princess, wheeling round on her, said —

"Gracious me, what's come over you, girl? Here you are to be mistress of the whole place within a month, I suppose, and yet – "

"Hush, Princess!"

There were footsteps in the hall, and at the next moment, Gordon, in his frock-coat uniform, looking flushed and excited, and accompanied by Hafiz, whose chubby face was wreathed in smiles, had entered the room.

After he had shaken hands with the Princess the servants rushed upon him – Mosie, who had come behind kissing his sword, Ibrahim his hand, and Fatimah struggling with an impulse to throw her arms about his neck.

"So you've come at last, have you?" said the Princess. "Time enough, too, for here's Helena of no use to anybody. Your father has gone back to England, hasn't he? He might have come up to see me, I think. He wrote a little letter to say good-bye, though. It was just like him. I could hear him speaking. 'My goodness,' I said, 'that's Nuneham!' Well, we shall never see his equal again. No, never! He might have left Egypt with twenty millions in his pocket, and he has gone with nothing but his wages. I suppose they're slandering him all the same. Ingrates! But no matter! The dogs bark, but the camel goes along. And now that I've time, let me take a look at you. What a colour! But what are you trembling about? Goodness me, has everybody got the jumps?"

Helena was the only one in the room who had not come forward to greet Gordon, and seeing his sidelong look in her direction, the Princess began to lay plans for leaving them together.

"Ibrahim," she cried, "hang up these naked babies in the bathroom – the only place for them, it seems to me. Fatimah, go back and look if the cooking-tins are not in the kitchen cupboard."

"They're not – I've looked already," said Fatimah.

"Then go and look again. Mosie, you want to inspect my horses – I can see you do."

"No, lady, I have i'spected them."

"Then i'spect them a second time. Off you go! … where's my lorgnette? Oh, dear me. I fancy I must have left it in the boudoir."

"Let me go for it, Princess," said Helena.

"Certainly not! Why should you? Do you think I'm a cripple that I can't go myself? Hafiz Effendi, where are your manners that you don't open this door for me? That's better. Now, the inner one."

At the next moment Gordon and Helena were left together. Helena was still standing by the window looking down at the city which seemed to lie dazed under the midday sun. Gordon stepped up and stood by her side. It was hard to realise that they were there again. But in spite of their happiness there was a little cloud over both. They knew what caused it.

While they stood together in silence they could hear the low reverberation of the voices of the people who were praying within the mosque.

"They are chanting the first Surah," said Gordon.

"Yes, the first Surah," said Helena.

Their hands found each other as they stood side by side.

"I saw Ishmael last night. He came to my quarters," said Gordon in a low tone.

"Well?" asked Helena faintly.

"It was most extraordinary. He came to tell me that … to compel me to – "

"Hush!"

There was a soft footstep behind them. It was the step of some one walking in Oriental slippers. Without turning round they knew who it was.

It was Ishmael. Notwithstanding his dusky complexion, his face was very pale – almost as white as his turban. His eyes looked weary, their light was almost extinct. Perhaps his sermon had exhausted him. It was almost as if there was no life left in him except the life of the soul. But he smiled – it was the smile of a spectre – as he stepped forward and held out his hand

Gordon's heart shuddered for pity. "Are you well?" he asked.

"Oh yes."

"But you look tired."

"It's nothing," said Ishmael; and then, with a touching simplicity, he added, "I have been troubled in my heart, but now I am at peace and all is well."

They sat, Ishmael on the sofa, Helena on a chair at his right, Gordon on a chair at his left, the window open before them, the city slumbering below.

Ishmael's face, though full of lines of pain, continued to smile, and his voice, though hoarse and faint, was cheerful. He had come to tell them that he was going away.

"Going away?" said Gordon.

"Yes, my work here is done, and when a man's work is done he stands outside of life. So I am going back."

"Back? You mean back to Khartoum?" asked Helena timidly.

"Perhaps there, too. But back to the desert. I am a son of the desert. Therefore what other place can be so good for me?"

"Are you going alone?"

"Yes! Or rather, no! When a man has lived, has laboured, he has always one thing – memory. And he who has memory can never be quite alone."

"Still you will be very lone – "

Ishmael turned to her with an almost imperceptible smile.

"Perhaps, yes, at first, a little lonely, and all the more so for the sweet glimpse I have had of human company."

"But this is not what you intended to … what you hoped to – "

"No! It's true I nourished other dreams for a while – dreams of living a human life after my work was done. It would have been very sweet, very beautiful. And now to go away, to give it up, never more to have part and lot in … never again to see those who … Yes, it's hard, a little hard."

Helena turned her head aside and looked out at the window.

"But that is all over now," said Ishmael. "Love is the crown of life, but it is not for all of us. Your great Master knew that as He knew everything. Some men have to be eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven's sake. How true! How right!"

His pallid face struggled to smile as he said this.

"And then what does our Prophet say (to him be prayer and peace)? 'The man who loves and never attains to the joy of his love, but renounces it for another who has more right to it, is as one who dies a martyr.'"

Still looking out at the window, Helena tried to say she would always remember him, and hoped he would be very happy.

"Thank you! That also will be a sweet memory," he said. "But happy moments are rare in the lives of those who are called to a work for humanity."

Then, coming gently to closer quarters, he told them he was there to say good-bye to them. "I had intended to write to you," he said, turning again to Helena, "but it is better so."

Then, facing towards Gordon, he said —

"I must confess that I have not always loved you. But I have been in the wrong, and I ask your pardon. It is God who governs the heart. And what does your divine Master say about that, too? 'Whom God hath joined together let not man put asunder.' That is the true word about love and marriage – the first, and the last, and the only one."

Then he rose, and both Helena and Gordon rose with him. One moment he stood between them without speaking, and then, stooping over Helena's hand and kissing it, he said, in a scarcely audible whisper —

"I divorce thee! I divorce thee! I divorce thee!"

It was the Mohammedan form of divorcement, and all that was necessary to set Helena free. When he raised his head his face was still smiling – a pitiful, heart-breaking smile.

Then, still holding Helena's hand, he reached out for Gordon's also, and said —

"I give her back to thee, my brother. And do not think I give what I would not keep. Perhaps – who knows? – perhaps I loved her too."

Helena was deeply affected. Gordon found it impossible to look into Ishmael's face. They felt his wearied eyes resting upon them; they felt their hands being brought together; they felt Ishmael's hand resting for a moment on their hands; and then they heard him say —

"Maa-es-salamah! Be happy! Keep together as long as you can. And never forget we shall meet some day."

Then, in a voice so low that they could scarcely hear it, he said —

"Peace be with you both! Peace!" – and passed out of the room.

They stood where he had left them in the middle of the room, with faces to the ground and their hands quivering in each other's clasp until the sound of his footsteps had died away. Then Gordon said —

"Shall we go into the garden, Helena?"

"Yes," she replied in a whisper.

They went out hand in hand, and walked to the arbour on the edge of the ramparts. There, on that loved spot, the past rolled back on them like billows of the soul. The bushes seemed to have grown, the bougainvillea was more purple than before, the air was full of the scent of blossom, and everything was turning to love and to song.

They did not speak, but they put their arms about each other, and looked down on the wide panorama below – the city, the Nile, the desert, the Pyramids, and that old, old Sphinx whose scarred face had witnessed so many incidents in the story of humanity, and was now witnessing the last incident of one story more.

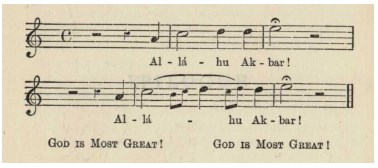

How long they stood there in their great happiness they never knew, but they were called back to themselves by a shrill, clear voice that came from a minaret behind them —

"God is Most Great! God is Most Great!"

Then, turning in the direction of the voice, they saw a white figure on a white camel ascending the yellow road that leads up to the fort on the top of the Mokattam hills and onward to the desert.

"Look," said Gordon. "Is it – ?"

Without speaking, Helena bent her head in assent.

With hands still clasped and quivering, they watched the white figure as it passed away. It stopped at the crest of the hill, and looked back for a moment; then turned again and went on. At the next moment it was gone.

And then once more came the voice from the minaret, like the voice of an angel winging its way through the air —

Music fragment

EPILOGUE

Lord Nuneham lived ten years longer, but never, after the first profound sensation caused by his retirement, was he heard of again. The House of Lords did not see him; he was never found on any public platform, and no publisher could prevail upon him to write the story of his life.

He bought a majestic but rather melancholy place in Berkshire, one of the great historic seats of an extinguished noble family, and there, under the high elms and amid the green and cloudy landscape of his own country, he lived out his last years in unbroken obscurity.

It has been well said that deep tragedy is the school of great men, but there was one ray of sunshine to brighten Lord Nuneham's solitude. On a table, by his bedside, in a room darkened by rustling leaves, stood two photographs in silver frames. They were of two boys, one dark like his mother, the other fair like his father, both bright and strong and clear-eyed. Down to the end the old man never went to bed without taking up these pictures and looking at them, and as often as he did so, a faint smile would pass over his seamed and weary face.

After a while the world forgot that he was alive, and when he died the public seemed to be taken by surprise. "I thought he died ten years ago," said somebody.

Gordon held his post as General in command of the British army in Egypt for four successive terms, his appointment being renewed, first by the wish of the War Office, and afterwards at the request of the Egyptian Government. The civil occupation having become less active since his father's time (the new Consul-General being a pale shadow of his predecessor), the military occupation became more important, and except for his subjection to headquarters, Gordon appeared to stand in the position of a military autocrat. But in the difficult and delicate task of maintaining order in a foreign country without exasperating the feelings of the native people, he showed great tact and sympathy. While allowing the utmost liberty to thought, whether political or religious, he never for a moment permitted it to be believed that the Government could be defied with impunity in matters affecting peace, order, life, and property.

For this the best elements honoured him, and when the poor and illiterate, who were sometimes the victims of extremists whose only aim was to throw flaming torches into pits of inflammable gas, saw that he was just as ready to put down lawlessness among Europeans as among Egyptians, they loved as well as trusted him. His life in Egypt lessened the gulf which Easterns always find between Christians and Christianity, and whenever he had to return to England, the streets of Cairo would be red with the tarbooshes of the people who ran to the railway-station to see him off. "Maa-es-salamah, brother!" they would say, with the simplicity of children, and then, "Don't forget we will be waiting for you to come back."

Gordon's love for the Egyptians never failed him, and he was entirely happy in his home, where Helena developed the summer bloom of beautiful womanhood, and where the light, merry sound of the voices of her two young boys was always ringing like music through the house.

It must be confessed that for a while Egypt had a hard and almost tragic time. After the Consul-General's departure she went through a period of storm and stress. There were both errors and crimes. These were the inevitable results of progressive stages of self-rule; and even anarchy, the travail of a nation's birth, was not altogether unknown. During the earlier years there were some to regret the absence of the mailed fist of Lord Nuneham, and to question the benefit of quasi-Western institutions in an Eastern country. But the atmosphere cleared at last, the sinister anticipations were falsified, a bold and magnanimous policy brought peace, and the destinies of Egypt were firmly united to those of the country that had given her a new lease of life and liberty.

England never regretted what she had done on that day, when, true to her high traditions, she decided that a great nation had no longer any right to govern, with absolute and undivided authority, another race living under another sky. And her reward seems likely to come in a way that might have been least expected. As "God chooseth His fleshly instruments and with imperfect hearts doeth His perfect work," He seems to have put it into the hearts of the Arab people to sink their tribal differences and to act at the prompting of the gigantic myth with which the Grand Cadi deceived the Consul-General.