полная версия

полная версияThe White Prophet, Volume II (of 2)

Suddenly, without warning, she burst into tears, for something in the tone of his voice rather than the strength of his words had made her feel the shame of the position she occupied in his eyes.

After a moment she recovered herself, and, in wild anger at her own weakness, she flamed out at him, saying that if she was Ishmael's wife it was in name only, that if she had married Ishmael it was only as a matter of form, at best a betrothal, in order to meet his own wish and to make it possible for her to go on with her purpose.

"As for love … our love … it is not I who have been false to it. No, never for one single moment … although … in spite of everything … for even when you were gone … when you had abandoned me … in the hour of my trouble, too … and I had lost all hope of you … I – "

"Then why, Helena? You hated Ishmael and wished to put him down while you thought he was coming between you and me. But why … when all seemed to be over between us – "

Her lips were twitching and her eyes were ablaze.

"You ask me why I wished to punish him?" she said. "Very well, I will tell you. Because – " she paused, hesitated, breathed hard, and then said, "because he killed my father."

Gordon gasped, his face became distorted, his lips grew pale, he tried to speak but could only stammer out broken exclamations.

"Great God! Hele – "

"Oh, you may not believe it, but I know," said Helena.

And then, with a rush of emotion, in a torrent of hot words, she told him how Ishmael Ameer had been the last man seen in her father's company; how she had seen them together and they were quarrelling; how her father had been found dead a few minutes after Ishmael had left him; how she had found him; how other evidence gave proof, abundant proof, that violence, as a contributory means at least, had been the cause of her father's death; and how the authorities knew this perfectly, but were afraid, in the absence of conclusive evidence, to risk a charge against one whom the people in their blindness worshipped.

"So I was left alone – quite alone – for you were gone too – and therefore I vowed that if there was no one else I would punish him."

"And that is what you – "

"Yes."

"O God! O God!"

Gordon hid his face in his hands, being made speechless by the awful strength of the blind force which had governed her life and led her into the tragic tangle of her error. But she misunderstood his feeling, and with flashing, almost blazing eyes, though sobs choked her voice for a moment, she turned on him and said —

"Why not? Think of what my father had been to me and say if I was not justified. Nobody ever loved me as he did – nobody. He was old, too, and weak, for he was ill, though nobody knew it. And then this … this barbarian … this hypocritical … Oh, when I think of it I have such a feeling of physical repulsion for the man that I can scarcely sit by his side."

Saying this she rose to her feet, and standing before Gordon, as he sat with his face covered by his hands, she said, with intense bitterness, as if exulting in the righteousness of her vengeance —

"Let him go to Damietta or to death itself if need be. Doesn't he deserve it? Doesn't he? Uncover your face and tell me. Tell me if … if … tell me if – "

She was approaching Gordon as if to draw away his hands when she began to gasp and stammer as though she had experienced a sudden electric shock. Her eyes had fallen on the third finger of his left hand, and they fixed themselves upon it with the fascination of fear. She saw that it was shorter than the rest, and that, since she had seen it before, it had been injured and amputated.

Her breath, which had been labouring heavily, seemed to stop altogether, and there was silence once more, in which the voice of Ishmael came again —

"When the Deliverer comes will he find peace on the earth? Will he find war? Will he find corruption and the worship of false gods? Will he find hatred and vengeance? Beware of vengeance, O my brothers! It corrupts the heart; it pulls down the pillars of the soul! Vengeance belongs to God, and when men take it out of His hands He writes black marks upon their faces."

The two unhappy people sitting together in the guest-room seemed to hear their very hearts beat. At length Gordon, making a great call on his resolution, began to speak.

"Helena!"

"Well?"

"It is all a mistake – a fearful, frightful mistake."

She listened without drawing breath – a vague foreshadowing of the truth coming over her.

"Ishmael Ameer did not kill your father."

Her lips trembled convulsively; she grew paler and paler every moment.

"I know he did not, Helena, because – " (he covered his face again) "because I know who did."

"Then who … who was it?"

"He did not intend to do it, Helena."

"Who was it?"

"It was all in the heat of blood."

"Who was – "

He hesitated, then stammered out, "Don't you see, Helena? – it was I."

She had known in advance what he was going to say, but not until he had said it did the whole truth fall on her. Then in a moment the world itself seemed to reel. A moral earthquake, upheaving everything, had brought all her aims to ashes. The mighty force which had guided and sustained her soul (the sense of doing a necessary and a righteous thing) had collapsed without an instant's warning. Another force, the powerful, almost brutal force of fate, had broken it to pieces.

"My God! My God! What has become of me?" she thought, and without speaking she gazed blankly at Gordon as he sat with his eyes hidden by his injured hand.

Then in broken words, with gasps of breath, he told her what had happened, beginning with the torture of his separation from her at the door of the General's house.

"You said I had not really loved you – that you had been mistaken and were punished and … and that was the end."

Going away with the memory of these words in his mind, his wretched soul had been on the edge of a vortex of madness in which all its anger, all its hatred, had been directed against the General. In the blind leading of his passion, torn to the heart's core, he had then returned to the Citadel to accuse the General of injustice and tyranny.

"'Helena was mine,' I said, 'and you have taken her from, me, and broken her heart as well as my own. Is that the act of a father?'"

Other words he had also said, in the delirium of his rage, mad and insulting words such as no father could bear; then the General had snatched up the broken sword from the floor and fallen on him, hacking at his hand – see!

"I didn't want to do it, God knows I did not, for he was an old man and I was no coward, but the hot blood was in my head, and I laid hold of him by the throat to hold him off."

He uncovered his face – it was full of humility and pain.

"God forgive me, I didn't know my strength. I flung him away; he fell. I had killed him – my General, my friend!"

Tears filled his eyes. In her eyes, also, tears were gathering.

"Then you came to the door and knocked. 'Father!' you said. 'Are you alone? May I come in?' Those were your words, and how often I have heard them since! In the middle of the night, in my dreams, O God, how many times!"

He dropped his head and stretched a helpless arm along the table.

"I wanted to open the door and say, 'Helena, forgive me, I didn't mean to do it, and that is the truth, as God is my witness.' But I was afraid – I fled away."

She was now sitting with her hands clasped in her lap and her eyelids tightly closed.

"Next day I wanted to go back to you, but I dared not do so. I wanted to comfort you – I could not. I wanted to give myself up to justice – it was impossible, there was nothing for me to do except to fly away."

The tears were rolling down his thin face to his pinched nostrils.

"But I could not fly from myself or from … from my love for you. They told me you had gone to England. 'Where is she to-night?' I thought. If I had never really loved you before I loved you now. And you were gone! I had lost you for ever."

Emotion choked his voice; tears were forcing themselves through her closed eyelids. There was another moment of silence and then, nervously, hesitatingly, she put out her hand to where his hand was lying on the table and clasped it.

The two unhappy creatures, like wrecked souls about to be swallowed up in a tempestuous ocean, saw one raft of hope – their love for each other, which had survived all the storms of their fate.

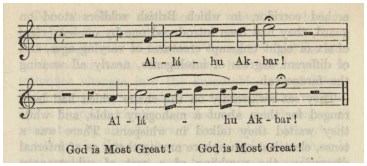

But just as their hands were burning as if with fever, and quivering in each other's clasp like the bosom of a captured bird, a voice from without fell on their ears like a trumpet from the skies. It was the voice of the muezzin calling to evening prayers from the minaret of the neighbouring mosque: —

Music fragment: God is Most Great! God is Most Great!

It seemed to be a supernatural voice, the voice of an accusing angel, calling them back to their present position. Ishmael – Helena – the betrothal!

Their hands separated and they rose to their feet. One moment they stood with bowed heads, at opposite sides of the table, listening to the voice outside, and then, without a word more, they went their different ways – he to his room, she to hers.

Into the empty guest-room, a moment afterwards, came the rumbling and rolling sound of the voices of the people, repeating the Fatihah after Ishmael —

"Praise be to God, the Lord of all creatures… Direct us in the right way, O Lord … not the way of those who go astray."

CHAPTER XIV

That day the Sirdar had held his secret meeting of the Ulema, the Sheikhs and Notables of Khartoum. Into a room on the ground floor of the Palace, down a dark, arched corridor, in which British soldiers stood on guard, they had been introduced one by one – a group of six or eight unkempt creatures of varying ages, and of different degrees of intelligence, nearly all wearing the farageeyah.

They sat awkwardly on the chairs which had been ranged for them about a mahogany table, and while they waited they talked in whispers. There was a tense, electrical atmosphere among them, as of internal dissension, the rumbling of a sort of subterranean thunder.

But this subsided instantly, when the voice of the sergeant outside, and the clash of saluting arms, announced the coming of the Sirdar. The Governor-General, who was in uniform and booted and spurred as if returning from a ride, was accompanied by his Inspector-General, his Financial Secretary, the Governor of the town, and various minor officers.

He was received by the Sheikhs, all standing, with sweeping salaams from floor to forehead, a circle of smiles and looks of complete accord.

The Sirdar, with his ruddy and cheerful face, took his seat at the head of the table and began by asking, as if casually, who was the stranger that had arrived that day in Khartoum.

"A Bedouin," said the Cadi. "One whom Ishmael Ameer loves and who loves him."

"Yet a Bedouin, you say?" asked the Sirdar, in an incredulous tone, and with a certain elevation of the eyebrows.

"A Bedouin, O Excellency," repeated the Cadi, whereupon the others, without a word of further explanation, bent their turbaned heads in assent.

Then the Sirdar explained the reason for which he had called them together.

"I am given to understand," he said, "that the idea is abroad that the Government has been trying to introduce changes into the immutable law of Islam, which forms an integral part of your Moslem religion, and is therefore rightly regarded with a high degree of veneration by all followers of the Prophet. If anybody is telling you this, or if any one is saying that there is any prejudice against you because you are Mohammedans, he is a wicked and mischievous person, and I beg of you to tell me who he is."

Saying this, the Sirdar looked sharply round the table, but met nothing but blank and expressionless faces. Then turning to the Cadi, who as Chief Judge of the Mohammedan law-courts had been constituted spokesman, he asked pointedly what Ishmael Ameer was saying.

"Nothing, O Excellency," said the Cadi; "nothing that is contrary to the Sharia – the religious law of Islam."

"Is he telling the people to resist the Government?"

The grave company about the table silently shook their heads.

"Do you know if he has anything to do with a conspiracy to resist the payment of taxes?"

The grave company knew nothing.

"Then what is he doing, and why has he come to Khartoum? Pasha, have you no explanation to make to me?" asked the Sirdar, singling out a vivacious old gentleman, with a short, white, carefully oiled beard – a person of doubtful repute who had once been a slave-dealer and was now living patriarchally, under the protection of the Government, with his many wives and concubines.

The old black sinner cast his little glittering eyes around the room and then said —

"If you ask me, O Master, I say, Ishmael Ameer is putting down polygamy and divorce and ought himself to be put down."

At that there was some clamour among the Ulema, and the Sirdar thought he saw a rift through which he might discover the truth, but the Pasha was soon silenced, and in a moment there was the same unanimity as before.

"Then what is he?" asked the Sirdar, whereupon a venerable old Sheikh, after the usual Arabic compliments and apologies, said that, having seen the new teacher with his own eyes and talked with him, he had now not the slightest doubt that Ishmael was a man sent from God, and therefore that all who resisted him, all who tried to put him down, would perish miserably. At these words the electrical atmosphere which had been held in subjection seemed to burst into flame. In a moment six tongues were talking together. One Sheikh, with wild eyes, told of Ishmael's intercourse with angels. Another knew a man who had seen him riding with the Prophet in the desert. A third had spoken to somebody who had seen angels, in the form of doves, descending upon him from the skies, and a fourth was ready to swear that one day, while Ishmael was preaching in the mosque, people heard a voice from heaven crying, "Hear him! He is My messenger!"

"What was he preaching about?" said the Sirdar.

"The last days, the coming of the Deliverer," said the Sheikh with the wild eyes, in an awesome whisper.

"What Deliverer?"

"Seyidna Isa – our Lord Jesus – the White Christ that is to come."

"Is this to be soon?"

"Soon, O Excellency, very soon."

After this outburst there was a moment of tense and breathless silence, during which the Sirdar sat with his serious eyes fixed on the table, and his officers, standing behind, glanced at each other and smiled.

Immediately afterwards the Sirdar put an end to the interview.

"Tell your people," he said, "that the Government has no wish to interfere with your religious beliefs and feelings, whatever they may be; but tell them also, that it intends to have its orders obeyed, and that any suspicion of conspiracy, still more of rebellion, will be instantly put down."

The group of unkempt creatures went off with sweeping salaams, and then the Sirdar dismissed his officers also, saying —

"Bear in mind that you are the recognised agents of a just and merciful Government, and whatever your personal opinions may be of these Arabs and their superstitions, please understand that you are to give no anti-Islamic colour to your British feelings. At the same time remember that we have worked for the redemption of the Soudan from a state of savagery, and we cannot allow it to be turned back to barbarism in the name of religion."

Both the Ulema and the other British officials being gone, the Sirdar was alone with his Inspector-General.

"Well?" he said.

"Well?" repeated the Inspector-General, biting the ends of his close-cropped moustache. "What more did you expect, sir? Naturally the man's own people were not going to give him away. They nearly did so, though. You heard what old Zewar Pasha said?"

"Tut! I take no account of that," said the Sirdar. "The brothers of Christ Himself would have put Him down, too – locked Him up in an asylum, I dare say."

"That's exactly what I would do with Ishmael Ameer, anyway," said the Inspector-General. "Of course he performs no miracles, and is attended by no angels. His removal to Torah, and his inability to free himself from a Government jail, would soon dispel the belief in his supernatural agencies."

"But how can we do it? Under what pretext? We can't imprison a man for preaching the second coming of Christ. If we did, our jails would be pretty full at home, I'm thinking."

The Inspector-General laughed. "Your old error, dear Sirdar. You can't apply the same principles to East and West."

"And your old Parliamentary cant, dear friend! I'm sick to death of it."

There was a moment of strained silence, and then the Inspector-General said —

"Ah well, I know these holy men, with their sham inspirations and their so-called heavenly messages. They develop by degrees, sir. This one has begun by proclaiming the advent of the Lord Jesus, and he will end by hoisting a flag and claiming to be the Lord Jesus himself."

"When he does that, Colonel, we'll consider our position afresh. Meantime it may do us no mischief to remember that if the family of Jesus could have dealt with the founder of our own religion as you would deal with this olive-faced Arab there would probably be no Christianity in the world to-day."

The Inspector-General shrugged his shoulders and rose to go.

"Good-night, sir."

"Good-night, Colonel," said the Sirdar, and then he sat down to draft a dispatch to the Consul-General —

"Nothing to report since the marriage, betrothal, or whatever it was, of the 'Rani' to the man in question. Undoubtedly he is laying a strong hold on the imagination of the natives and acquiring the allegiance of large bodies of workers; but I cannot connect him with any conspiracy to persuade people not to pay taxes or with any organised scheme that is frankly hostile to the continuance of British rule.

"Will continue to watch him, but find myself at fearful odds owing to difference of faith. It is one of the disadvantages of Christian Governments among people of alien race and religion, that methods of revolt are not always visible to the naked eye, and God knows what is going on in the sealed chambers of the mosque.

"That only shows the danger of curtailing the liberty of the vernacular press, whatever the violence of its sporadic and muddled anarchy. Leave the press alone, I say. Instead of chloroforming it into silence give it a tonic if need be, or you drive your trouble underground. Such is the common sense and practical wisdom of how to deal with sedition in a Mohammedan country, let some of the logger-headed dunces who write leading articles in England say what they will.

"If this man should develop supernatural pretensions I shall know what to do. But without that, whether he claim divine inspiration or not, if his people should come to regard him as divine, the very name and idea of his divinity may become a danger, and I suppose I shall have to put him under arrest."

Then remembering that he was addressing not only the Consul-General but a friend, the Sirdar wrote —

"'Art Thou a King?' Strange that the question of Pontius Pilate is precisely what we may find in our own mouths soon! And stranger still, almost ludicrous, even farcical and hideously ironical, that though for two thousand years Christendom has been spitting on the pusillanimity of the old pagan, the representative of a Christian Empire will have to do precisely what he did.

"Short of Pilate's situation, though, I see no right to take this man, so I am not taking him. Sorry to tell you so, but I cannot help it.

"Our love from both to both. Trust Janet is feeling better. No news of our poor boy, I suppose?"

"Our boy" had for thirty years been another name for Gordon.

CHAPTER XV

Grave as was the gathering in the Sirdar's Palace at Khartoum, there was a still graver gathering that day at the British Agency in Cairo – the gathering of the wings of Death.

Lady Nuneham was nearing her end. Since Gordon's disgrace and disappearance she had been visibly fading away under a burden too heavy for her to bear.

The Consul-General had been trying hard to shut his eyes to this fact. More than ever before, he had immersed himself in his work, being plainly impelled to fresh efforts by hatred of the man who had robbed him of his son.

Through the Soudan Intelligence Department in Cairo he had watched Ishmael's movements in Khartoum, expecting him to develop the traits of the Mahdi and thus throw himself into the hands of the Sirdar.

It was a deep disappointment to the Consul-General that this did not occur. The same report came to him. again and again. The man was doing nothing to justify his arrest. Although surrounded by fanatical folk, whose minds were easily inflamed, he was not trying to upset governors or giving "divine" sanction for the removal of officials.

But meantime some mischief was manifestly at work all over the country. From day to day Inspectors had been coming in to say that the people were not paying their taxes. Convinced that this was the result of conspiracy, the Consul-General had shown no mercy.

"Sell them up," he had said, and the Inspectors, taking their cue from his own spirit but exceeding his orders, had done his work without remorse.

Week by week the trouble had deepened, and when disturbances had been threatened he had asked the British Army of Occupation, meaning no violence, to go out into the country and show the people England's power.

Then grumblings had come down on him from the representatives of foreign nations. If the people were so discontented with British rule that they were refusing to pay their taxes, there would be a deficit in the Egyptian treasury – how then were Egypt's creditors to be paid?

"Time enough to cross the bridge when you come to it, gentlemen," said the Consul-General, in his stinging tone and with a curl of his iron lip.

If the worst came to the worst England would pay, but England should not be asked to do so because Egypt must meet the cost of her own government. Hence more distraining and some inevitable violence in suppressing the riots that resulted from evictions.

Finally came a hubbub in Parliament, with the customary "Christian" prattlers prating again. Fools! They did not know what a subtle and secret conspiracy he had to deal with while they were crying out against his means of killing it.

He must kill it! This form of passive resistance, this attack on the Treasury, was the deadliest blow that had ever yet been aimed at England's power in Egypt.

But he must not let Europe see it! He must make believe that nothing was happening to occasion the least alarm. Therefore to drown the cries of the people who were suffering not because they were poor and could not pay, but because they were perverse and would not, he must organise some immense demonstration.

Thus came to the Consul-General the scheme of the combined festival of the King's Birthday and the – th anniversary of the British Occupation of Egypt. It would do good to foreign Powers, for it would make them feel that, not for the first time, England had been the torch-bearer in a dark country. It would do good to the Egyptians, too, for it would force their youngsters (born since Tel-el-Kebir) to realise the strength of England's arm.

Thus had the Consul-General occupied himself while his wife had faded away. But at length he had been compelled to see that the end was near, and towards the close of every day he had gone to her room and sat almost in silence, with bowed head, in the chair by her side.

The great man, who for forty years had been the virtual ruler of millions, had no wisdom that told him what to say to a dying woman; but at last, seeing that her pallor had become whiteness, and that she was sinking rapidly and hungering for the consolations of her religion, he asked her if she would like to take the sacrament.

"It is just what I wish, dear," she answered, with the nervous smile of one who had been afraid to ask.