полная версия

полная версияThirty Years' View (Vol. II of 2)

Mr. B. here exhibited a table showing the actual state of the navy, in point of numbers, at the commencement of the years 1841 and 1842; and showed that the increase in one year was nearly as great as it had been in the previous twenty years; and that its totality at the latter of these periods was between eleven and twelve thousand men, all told. This is what the present administration has done in one year – the first year of its existence: and it is only the commencement of their plan – the first step in a long succession of long steps. The further increases, still contemplated were great, and were officially made known to the Congress, and the estimates increased accordingly. To say nothing of what was in the Senate in its executive capacity, Mr. B. would read a clause from the report of the Senate's Committee on Naval Affairs, which showed the number of vessels which the Secretary of the Navy proposed to have in commission, and the consequent vast increase of men and money which would be required. (The following is the extract from Mr. Bayard's report):

"The second section of the act of Congress of the 21st April, 1806, expressly authorizes the President 'to keep in actual service, in time of peace, so many of the frigates and other public armed vessels of the United States, as in his judgment the nature of the service may require.' In the exercise of this discretion, the committee are informed by the Secretary of the Navy that he proposes to employ a squadron in the Mediterranean, consisting of two ships of the line, four frigates, and four sloops and brigs – in all, ten vessels; another squadron on the Brazil station, consisting, also, of two ships-of-the-line, four frigates, and four sloops and brigs; which two squadrons will be made from time to time to exchange their stations, and thus to traverse the intermediate portion of the Atlantic. He proposes, further, to employ a squadron in the Pacific, consisting of one ship-of-the-line, two frigates, and four sloops; and a similar squadron of one ship of the line, two frigates, and four sloops in the East Indies; which squadrons, in like manner, exchanging from time to time their stations, will traverse the intermediate portion of the Pacific, giving countenance and protection to the whale fishery in that ocean. He proposes, further, to employ a fifth squadron, to be called the home squadron, consisting of one ship-of-the-line, three frigates, and three sloops, which, besides the duties which its name indicates, will have devolved upon it the duties of the West India squadron, whose cruising ground extended to the mouth of the Amazon, and as far as the 30th degree of west longitude from London. He proposes, additionally, to employ on the African coast one frigate and four sloops and brigs – in all, five vessels; four steamers in the Gulf of Mexico, and four steamers on the lakes. There will thus be in commission seven ships-of-the-line, sixteen frigates, twenty-three sloops and brigs, and eight steamers – in all, fifty-four vessels."

This is the report of the committee. This is what we are further to expect. Five great squadrons, headed by ships of the line; and one of them that famous home squadron hatched into existence at the extra session one year ago, and which is the ridicule of all except those who live at home upon it, enjoying the emoluments of service without any service to perform. Look at it. Examine the plan in its parts, and see the enormity of its proportions. Two ships-of-the-line, four frigates, and four sloops and brigs for the Mediterranean – a sea as free from danger to our commerce as is the Chesapeake Bay. Why, sir, our Secretary is from the land of Decatur, and must have heard of that commander, and how with three little frigates, one sloop, and a few brigs and schooners, he humbled Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis, and put an end to their depredations on American ships and commerce. He must have heard of Lord Exmouth, who, with less force than he proposes to send to the Mediterranean, went there and crushed the fortifications of Algiers, and took the bond of the pirates never to trouble a Christian again. And he must have heard of the French, who, since 1830, are the owners of Algiers. Certainly the Mediterranean is as free from danger to-day as is the Chesapeake Bay; and yet our Secretary proposes to send two ships-of-the-line, four frigates, and four sloops to that safe sea, to keep holiday there for three years. Another squadron of the same magnitude is to go to Brazil, where a frigate and a sloop would be the extent that any emergency could require, and more than has ever been required yet. The same of the Pacific Ocean, where Porter sailed in triumph during the war with one little frigate; and a squadron to the East Indies, where no power has any navy, and where our sloops and brigs would dominate without impediment. In all fifty-four men-of-war! Seven ships-of-the-line, sixteen frigates, twenty-three sloops and brigs, and eight steamers. And all this under Jefferson's act of 1806, when there was not a ship-of-the-line, nor a large frigate, nor twenty vessels of all sorts, and part of them to remain in port – only the number going forth that would require nine hundred and twenty-five men to man them! just about the complement of one of these seven ships-of-the-line. Does not presidential discretion want regulating when such things as these can be done under the act of 1806? Has any one calculated the amount of this increase, and counted up the amount of men and money which it will cost? The report does not, and, in that respect, is essentially deficient. It ought to be counted, and Mr. B. would attempt it. He acknowledged the difficulty of such an undertaking; how easy it was for a speaker – and especially such a speaker as he was – to get into a fog when he got into masses of millions, and so bewilder others as well as himself. To avoid this, details must be avoided, and results made plain by simplifying the elements of calculation. He would endeavor to do so, by taking a few plain data, in this case – the data correct in themselves, and the results, therefore, mathematically demonstrated.

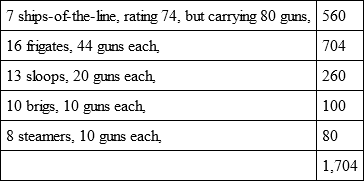

He would take the guns and the men – show what we had now, and what we proposed to have; and what was the cost of each gun afloat, and the number of men to work it. The number of guns we now have afloat is nine hundred and thirty-seven; the number of men between eleven and twelve thousand; and the estimated cost for the whole, a fraction over eight millions of dollars. This would give about twelve men and about nine thousand dollars to each gun. [Mr. Bayard asked how could these nine thousand dollars a gun be made out?] Mr. Benton replied. By counting every thing that was necessary to give you the use of the gun – every thing incident to its use – every thing belonging to the whole naval establishment. The end, design, and effect of the whole establishment, was to give you the use of the gun. That was all that was wanted. But, to get it, an establishment had to be kept up of vast extent and variety – of shops and yards on land, as well as ships at sea – of salaries and pensions, as well as powder and balls. Every expense is counted, and that gives the cost per gun. Mr. B. said he would now analyze the gentleman's report, and see what addition these five squadrons would make to the expense of the naval establishment. The first point was, to find the number of guns which they were to bear, and which was the element in the calculation that would lead to the results sought for. Recurring to the gentleman's report, and taking the number of each class of vessels, and the number of guns which each would carry, and the results would be:

Here (said Mr. B.) is an aggregate of 1,704 guns, which, at $9,000 each gun, would give $15,336,000, as the sum which the Treasury would have to pay for a naval establishment which would give us the use of that number. Deduct the difference between the 937, the present number of guns, and this 1,704, and you have 767 for the increased number of guns, which, at $9,000 each, will give $6,903,000 for the increased cost in money. This was the moneyed result of the increase. Now take the personal increase – that is to say, the increased number of men which the five squadrons would require. Taking ten men and two officers to the gun – in all, twelve – and the increased number of men and officers required for 767 guns would be 8,204. Add these to the 11,000 or 12,000 now in service, and you have close upon 20,000 men for the naval peace establishment of 1843, costing about fifteen millions and a half of dollars.

But I am asked, and in a way to question my computation, how I get at these nine thousand dollars cost for each gun afloat? I answer – by a simple and obvious process. I take the whole annual cost of the navy department, and then see how many guns we have afloat. The object is to get guns afloat, and the whole establishment is subordinate and incidental to that object. Not only the gun itself, the ship which carries it, and the men who work it, are to be taken into the account, but the docks and navy-yards at home, the hospitals and pensions, the marines and guards – every thing, in fact, which constituted the expense of the naval establishment. The whole is employed, or incurred, to produce the result – which is, so many guns at sea to be fired upon the enemy. The whole is incurred for the sake of the guns, and therefore all must be counted. Going by this rule (said Mr. B.), it would be easily shown that his statement of yesterday was about correct – rather under than over; and this could be seen by making a brief and plain sum in arithmetic. We have the number of guns afloat, and the estimated expense for the year: the guns 936; the estimate for the year is $8,705,579. Now, divide this amount by the number of guns, and the result is a little upwards of $9,200 to each one. This proves the correctness of the statement made yesterday; it proves it for the present year, which is the one in controversy. The result will be about the same for several previous years. Mr. B. said he had looked over the years 1841 and 1838, and found this to be the result: in 1841, the guns were 747, and the expense of the naval establishment $6,196,516. Divide the money by the guns, and you have a little upwards of $8,300. In 1838, the guns were 670, and the expense $5,980,971. This will give a little upwards of $8,900 to the gun. The average of the whole three years will be just about $9,000.

Thus, the senator from New Hampshire [Mr. Woodbury] and himself were correct in their statement, and the figures proved it. At the same time, the senator from Delaware [Mr. Bayard] is undoubtedly correct in taking a small number of guns, and saying they may be added without incurring an expense of more than three or four thousand dollars. Small additions may be made, without incurring any thing but the expense of the gun itself, and the men who work it. But that is not the question here. The question is to almost double the number; it is to carry up 937 to 1,700. Here is an increase intended by the Secretary of the Navy of near 800 guns – perhaps quite 800, if the seventy-fours carry ninety guns, as intimated by the senator [Mr. Bayard] this day. These seven or eight hundred guns could not be added without ships to carry them, and all the expense on land which is incident to the construction of these ships. These seven or eight hundred additional guns would require seven or eight thousand men, and a great many officers. Ten men and two officers to the gun is the estimate. The present establishment is near that rate, and the increase must be in the same proportion. The present number of men in the navy, exclusive of officers, is 9,784: which is a fraction over ten to the gun. The number of officers now in service (midshipmen, surgeons, &c., included) is near 1,300, besides the list of nominations not yet confirmed. This is in the proportion of nearly one and a half to a gun. Apply the whole to the intended increase – the increase which the report of the committee discloses to us – and you will have close upon 17,000 men and 2,000 officers for the peace establishment of the navy – in all, near 20,000 men! and this, independent of those employed on land, and the 2,000 mechanics and laborers who are usually at our navy-yards. Now, these men and officers cost money: two hundred and twenty-six dollars per annum per man, and eight hundred and fifty dollars per annum per officer, was the average cost in 1833, as stated in the report of the then Secretary of the Navy, the present senator from New Hampshire [Mr. Woodbury]. What it is now, Mr. B. did not know, but knew it was greater for the officers now, than it was then. But one thing he did know – and that was, that a naval peace establishment of the magnitude disclosed in the committee's report (six squadrons, 54 vessels, 1,700 guns, 17,000 men, and 2,000 or 3,000 officers) would break down the whole navy of the United States.

Mr. B. said we had just had a presidential election carried on a hue-and-cry against extravagance, and a hurrah for a change, and a promise to carry on the government for thirteen millions of dollars; and here were fifteen and a half millions for one branch of the service! and those who oppose it are to be stigmatized as architects of ruin, and enemies of the navy; and a hue-and-cry raised against them for the opposition. He said we had just voted a set of resolutions [Mr. Clay's] to limit the expenses of the government to twenty-two millions; and yet here are two-thirds of that sum proposed for one branch of the service – a branch which, under General Jackson's administration, cost about four millions, and was intended to be limited to about that amount. This was the economy – the retrenchment – the saving of the people's money, which was promised before the election!

Mr. B. would not go into points so well stated by the senator from New Hampshire [Mr. Woodbury] on yesterday, that our present peace naval establishment exceeds the cost of the war establishment during the late war; that we pay far more money, and get much fewer guns and men than the British do for the same money. He would omit the tables which he had on hand to prove these important points, and would go on to say that it was an obligation of imperious duty on Congress to arrest the present state of things; to turn back the establishment to what it was a year ago; and to go to work at the next session of Congress to regulate the United States naval peace establishment by law. When that bill came up, a great question would have to be decided – the question of a navy for defence, or for offence! When that question came on, he would give his opinion upon it, and his reasons for that opinion. A navy of some degree, and of some kind, all seemed to be agreed upon; but what it is to be – whether to defend our homes, or carry war abroad – is a question yet to be decided, and on which the wisdom and the patriotism of the country would be called into requisition. He would only say, at present, that coasts and cities could be defended without great fleets at sea. The history of continental Europe was full of the proofs. England, with her thousand ships, could do nothing after Europe was ready for her, during the late wars of the French revolution. He did not speak of attacks in time of peace, like Copenhagen, but of Cadiz and Teneriffe in 1797, and Boulogne and Flushing in 1804, where Nelson, with all his skill and personal daring, and with vast fleets, was able to make no impression.

Mr. B. said the navy was popular, and had many friends and champions; but there was such a thing as killing by kindness. He had watched the progress of events for some time, and said to his friends (for he made no speeches about it) that the navy was in danger – that the expense of it was growing too fast – that there would be reaction and revulsion. And he now said that, unless things were checked, and moderate counsels prevailed, and law substituted for executive discretion (or indiscretion, as the case might be), the time might not be distant when this brilliant arm of our defence should become as unpopular as it was in the time of the elder Mr. Adams.

CHAPTER CIX.

MESSAGE OF THE PRESIDENT AT THE OPENING OF THE REGULAR SESSION OF 1842-3

The treaty with Great Britain, and its commendation, was the prominent topic in the forepart of the message. The President repeated, in a more condensed form, the encomiums which had been passed upon it by its authors, but without altering the public opinion of its character – which was that it was really a British treaty, Great Britain getting every thing settled which she wished, and all to her own satisfaction; while all the subjects of interest to the United States were adjourned to an indefinite future time, as well known then as now never to occur. One of these deferred subjects was a matter of too much moment, and pregnant with too grave consequences, to escape general reprobation in the United States: it was that of the Columbia River, exclusively possessed by the British under a joint-occupation treaty: and which possession only required time to ripen it into a valid title. The indefinite adjournment of that question was giving Great Britain the time she wanted; and the danger of losing the country was turning the attention of the Western people towards saving it by sending emigrants to occupy it. Many emigrants had gone: more were going: a tide was setting in that direction. In fact the condition of this great American territory was becoming a topic of political discussion, and entering into the contests of party; and the President found it necessary to make further excuses for omitting to settle it in the Ashburton treaty, and a necessity to attempt to do something to soothe the public mind. He did so in this message:

"It would have furnished additional cause for congratulation, if the treaty could have embraced all subjects calculated in future to lead to a misunderstanding between the two governments. The territory of the United States, commonly called the Oregon Territory, lying on the Pacific Ocean, north of the forty-second degree of latitude, to a portion of which Great Britain lays claim, begins to attract the attention of our fellow-citizens; and the tide of population, which has reclaimed what was so lately an unbroken wilderness in more contiguous regions, is preparing to flow over those vast districts which stretch from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. In advance of the acquirement of individual rights to these lands, sound policy dictates that every effort should be resorted to by the two governments to settle their respective claims. It became manifest, at an early hour of the late negotiations, that any attempt, for the time being, satisfactorily to determine those rights, would lead to a protracted discussion which might embrace, in its failure, other more pressing matters; and the Executive did not regard it as proper to waive all the advantages of an honorable adjustment of other difficulties of great magnitude and importance, because this, not so immediately pressing, stood in the way. Although the difficulty referred to may not, for several years to come, involve the peace of the two countries, yet I shall not delay to urge on Great Britain the importance of its early settlement."

The excuse given for the omission of this subject in the Ashburton negotiations is lame and insufficient. Protracted discussion is incident to all negotiations, and as to losing other matters of more pressing importance, all that were of importance to the United States were given up any way, and without getting any equivalents for them. The promise to urge an early settlement could promise but little fruit after Great Britain had got all she wanted; and the discouragement of settlement, by denying land titles to the emigrants until an adjustment could be made, was the effectual way to abandon the country to Great Britain. But this subject will have an appropriate chapter in the history of the proceedings of Congress to encourage that emigration which the President would repress.

The termination of the Florida war was a subject of just congratulation with the President, and was appropriately communicated to Congress.

"The vexatious, harassing, and expensive war which so long prevailed with the Indian tribes inhabiting the peninsula of Florida, has happily been terminated; whereby our army has been relieved from a service of the most disagreeable character, and the Treasury from a large expenditure. Some casual outbreaks may occur, such as are incident to the close proximity of border settlers and the Indians; but these, as in all other cases, may be left to the care of the local authorities, aided, when occasion may require, by the forces of the United States."

The President does not tell by what treaty of peace this war was terminated, nor by what great battle it was brought to a conclusion: and there were none such to be told – either of treaty negotiated, or of battle fought. The war had died out of itself under the arrival of settlers attracted to its theatre by the Florida armed occupation act. No sooner did the act pass, giving land to each settler who should remain in the disturbed part of the territory five years, than thousands repaired to the spot. They went with their arms and ploughs – the weapons of war in one hand and the implements of husbandry in the other – their families, flocks and herds, established themselves in blockhouses, commenced cultivation, and showed that they came to stay, and intended to stay. Bred to the rifle and the frontier, they were an overmatch for the Indians in their own mode of warfare; and, interested in the peace of the country, they soon succeeded in obtaining it. The war died out under their presence, and no person could tell when, nor how; for there was no great treaty held, or great battle fought, to signalize its conclusion. And this is the way to settle all Indian wars – the cheap, effectual and speedy way to do it: land to the armed settler, and rangers, when any additional force is wanted – rangers, not regulars.

But a government bank, under the name of exchequer, was the prominent and engrossing feature of the message. It was the same paper-money machine, borrowed from the times of Sir Robert Walpole, which had been recommended to Congress at the previous session and had been so unanimously repulsed by all parties. Like its predecessor it ignored a gold and silver currency, and promised paper. The phrases "sound currency" – "sound circulating medium" – "safe bills convertible at will into specie," figured throughout the scheme; and to make this government paper a local as well as a national currency, the denomination of its notes was to be carried down at the start to the low figure of five dollars – involving the necessity of reducing it to one dollar as soon as the banishment of specie which it would create should raise the usual demand for smaller paper. To do him justice, his condensed argument in favor of this government paper, and against the gold and silver currency of the constitution, is here given:

"There can be but three kinds of public currency: 1st. Gold and silver; 2d. The paper of State institutions; or, 3d. A representative of the precious metals, provided by the general government, or under its authority. The sub-treasury system rejected the last, in any form; and, as it was believed that no reliance could be placed on the issues of local institutions, for the purposes of general circulation, it necessarily and unavoidably adopted specie as the exclusive currency for its own use. And this must ever be the case, unless one of the other kinds be used. The choice, in the present state of public sentiment, lies between an exclusive specie currency on the one hand, and government issues of some kind on the other. That these issues cannot be made by a chartered institution, is supposed to be conclusively settled. They must be made, then, directly by government agents. For several years past, they have been thus made in the form of treasury notes, and have answered a valuable purpose. Their usefulness has been limited by their being transient and temporary; their ceasing to bear interest at given periods, necessarily causes their speedy return, and thus restricts their range of circulation; and being used only in the disbursements of government, they cannot reach those points where they are most required. By rendering their use permanent, to the moderate extent already mentioned, by offering no inducement for their return, and by exchanging them for coin and other values, they will constitute, to a certain extent, the general currency so much needed to maintain the internal trade of the country. And this is the exchequer plan, so far as it may operate in furnishing a currency."