полная версия

полная версияThirty Years' View (Vol. II of 2)

"This was the age of interested projects, inspired by a venal spirit of adventure, the natural consequence of that avarice, fraud, and profligacy which the MONEYED CORPORATIONS had introduced. The vice, luxury, and prostitution of the age – the almost total extinction of sentiment, honor, and public spirit – had prepared the minds of men for slavery and corruption. The means were in the hands of the ministry: the public treasure was at their devotion: they multiplied places and pensions, to increase the number of their dependents: they squandered away the national treasure without taste, discernment, decency, or remorse: they enlisted an army of the most abandoned emissaries, whom they employed to vindicate the worst measures in the face of truth, common sense, and common honesty; and they did not fail to stigmatize as Jacobites, and enemies to the government, all those who presumed to question the merit of their administration. The interior government of Great Britain was chiefly managed by Sir Robert Walpole, a man of extraordinary talents, who had from low beginnings raised himself to the head of the ministry. Having obtained a seat in the House of Commons, he declared himself one of the most forward partisans of the whig faction. He was endued with a species of eloquence which, though neither nervous nor elegant, flowed with great facility, and was so plausible on all subjects, that even when he misrepresented the truth, whether from ignorance or design, he seldom failed to persuade that part of his audience for whose hearing his harangue was chiefly intended. He was well acquainted with the nature of the public funds, and understood the whole mystery of stockjobbing. This knowledge produced a connection between him and the MONEY CORPORATIONS, which served to enhance his importance."

Such was the picture of Great Britain in the time of Sir Robert Walpole, and such was the natural fruit of a stockjobbing government, composed of bank and state, resting for support on heartless corporations, and lending the wealth and credit of the country to the interested schemes of projectors and adventurers. Such was the picture of Great Britain during this period; and who would not mistake it (leaving out names and dates) for a description of our own times, in our own America, during the existence of the Bank of the United States and the thousand affiliated institutions which grew up under its protection during its long reign of power and corruption? But, to proceed, with English history:

Among the corporations brought into existence by Sir Robert Walpole, or moulded by him into the form which they have since worn, were the South Sea Company, the East India Company, the Bank of England, the Royal Insurance Company, the London Insurance Company, the Charitable Corporation, and a multitude of others, besides the exchequer and funding systems, which were the machines for smuggling debts and taxes upon the people and saddling them on posterity. All these schemes were brought forward under the pretext of paying the debts of the nation, relieving the distresses of the people, assisting the poor, encouraging agriculture, commerce, and manufactures; and saving the nation from the burden of loans and taxes. Such were the pretexts for all the schemes. They were generally conceived by low and crafty adventurers, adopted by the minister, carried through parliament by bribery and corruption, flourished their day; and ended in ruin and disgrace. A brief notice of the origin and pretensions of the South Sea scheme, may serve for a sample of all the rest, and be an instructive lesson upon the wisdom of all government projects for the relief of the people. I say, a notice of its origin and pretensions; for the progress and termination of the scheme are known to everybody, while few know (what the philosophy of history should be most forward to teach) that this renowned scheme of fraud, disgrace, and ruin, was the invention of a London scrivener, adopted by the king and his minister, passed through parliament by bribes to the amount of £574,000; and that its vaunted object was to pay the debts of the nation, to ease the burdens of the subject, to encourage the industry of the country, and to enrich all orders of men. These are the things which should be known; these are the things which philosophy, teaching by the example of history, proposes to tell, in order that the follies of one age or nation may be a warning to others; and this is what I now want to show. I read again from the same historian:

"The king (George I.) having recommended to the Commons the consideration of proper means for lessening the national debt, was a prelude to the famous South Sea act, which became productive of so much mischief and infatuation. The scheme was projected by Sir John Blunt, who had been bred a scrivener, and was possessed of all the cunning, plausibility and boldness requisite for such an undertaking. He communicated his plan to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, as well as to one of the Secretaries of State. He answered all their objections, and the plan was adopted. They foresaw their own private advantage in the execution of the design. The pretence for the scheme was to discharge the national debt, by reducing all the funds into one. The Bank and the South Sea Company outbid each other. The South Sea Company altered their original plan, and offered such high terms to government that the proposals of the Bank were rejected: and a bill was ordered to be brought into the House of Commons, formed on the plan presented by the South Sea Company. The bill passed without amendment or division; and on the 7th day of April, 1720, received the royal assent. Before any subscription could be made, a fictitious stock of £574,000 had been disposed of by the directors to facilitate the passing of the bill. Great part of this was distributed among the Earl Sunderland, Mr. Craggs, Secretary of State, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Duchess of Kendall, the Countess of Platen, and her two nieces" (mistresses of the king, &c.)

This is a sample of the origin and pretensions of nearly all the great corporations which were chartered and patronized by the Walpole whigs: all of them brought forward under the pretext of relieving the people and the government – nearly all of them founded in fraud or folly – carried through by corruption – and ending in disgrace and calamity. Leaving out names, and who would not suppose that I had been reading the history of our own country in our own times? The picture suits the United States in 1840 as well as it suited England in 1720: but at one point, the comparison, if pushed a step further, would entirely fail; all these corporation plunderers were punished in England! Though favored by the king and ministry, they were detested by the people, and pursued to the extremity of law and justice. The South Sea swindlers were fined and imprisoned – their property confiscated – their names attainted – and themselves declared incapable of holding any office of honor or profit in the kingdom. The president and cashier of the charitable corporation – (which was chartered to relieve the distresses of the poor, and which swindled the said poor out of £600,000 sterling) – this president and this cashier were pursued into Holland – captured – brought back – criminally punished – and made to disgorge their plunder. Others, authors and managers of various criminal corporations, were also punished: and in this the parallel ceases between the English times and our own. With us, the swindling corporations are triumphant over law and government. Their managers are in high places – give the tone to society – and riot in wealth. Those who led, or counselled the greatest ruin which this, or any country ever beheld – the Bank of the United States – these leaders, their counsellors and abettors, are now potential with the federal government – furnish plans for new systems of relief – and are as bold and persevering as ever in seizing upon government money and government credit to accomplish their own views. In all this, the parallel ceases; and our America sinks in the comparison.

Corporation credit was ruined in Great Britain, by the explosions of banks and companies – by the bursting of bubbles – by the detection of their crimes – and by the crowning catastrophe of the South Sea scheme: it is equally ruined with us, and by the same means, and by the crowning villany of the Bank of the United States. Bank and state can no longer go together in our America: the government can no longer repose upon corporations. This is the case with us in 1841; and it was the case with Great Britain in 1720. The South Sea explosion dissolved (for a long time) the connection there; the explosion of the Bank of the United States has dissolved it here. New schemes become indispensable: and in both countries the same alternative is adopted. Having exhausted corporation credit in England, the Walpole whigs had recourse to government credit, and established a Board of Exchequer, to strike government paper. In like manner, the new whigs, having exhausted corporation credit with us, have recourse to government credit to supply its place; and send us a plan for a federal exchequer, copied with such fidelity of imitation from the British original that the description of one seems to be the description of the other. Of course I speak of the exchequer feature of the plan alone. For as to all the rest of our cabinet scheme – its banking and brokerage conceptions – its exchange and deposit operations – its three dollar issues in paper for one dollar specie in hand – its miserable one-half of one per centum on its Change-alley transactions – its Cheapside under-biddings of rival bankers and brokers: – as to all these follies (for they do not amount to the dignity of errors) they are not copied from any part of the British exchequer system, or any other system that I ever heard of, but are the uncontested and unrivalled production of our own American genius. I repeat it: our administration stands to-day where the British government stood one hundred and twenty years ago. Corporation credit exhausted, public credit is resorted to; and the machinery of an exchequer of issues becomes the instrument of cheating and plundering the people in both countries. The British invent: we copy: and the copy proves the scholar to be worthy of the master. Here is the British act. Let us read some parts of it: and recognize in its design, its structure, its object, its provisions, and its machinery, the true original of this plan (the exchequer part) which the united wisdom of our administration has sent down to us for our acceptance and ratification. I read, not from the separate and detached acts of the first and second George, but from the revised and perfected system as corrected and perpetuated in the reign of George the Third. (Here Mr. Benton compared the two systems through the twenty sections which compose the British act, and the same number which compose the exchequer bill of this administration.)

Here, resumed Mr. B. is the original of our exchequer scheme! here is the original of which our united administration has unanimously sent us down a faithful copy. In all that relates to the exchequer – its design – operation – and mode of action – they are one and the same thing! identically the same. The design of both is to substitute government credit for corporation credit – to strike paper money for the use of the government – to make this paper a currency, as well as a means of raising loans – to cover up and hide national debt – to avoid present taxes in order to increase them an hundred fold in future – to throw the burdens of the present day upon a future day; and to load posterity with our debts in addition to their own. The design of both is the same, and the structure of both is the same. The English board consists of the lord treasurer for the time being, and three commissioners to be appointed by the king; our board is to consist of the Secretary of the Treasury and the Treasurer for the time being, and three commissioners to be appointed by the President and Senate. The English board is to superintend and direct the form and mode of preparing and issuing the exchequer bills; our board is to do the same by our treasury notes. The English bills are to be receivable in all payments to the public; our treasury notes are to be received in like manner in all federal payments. The English board appoints paymasters, clerks and officers to assist them in the work of the exchequer; ours is to appoint agents in the States, with officers and clerks to assist them in the same work. The English paymasters are to give bonds, and be subject to inspection; our agents are to do and submit to the same. The English exchequer bills are to serve for a currency; and for that purpose the board may contract with persons, bodies politic and corporate, to take and circulate them; our board is to do the same thing through its agencies in the States and territories. The English exchequer bills are to be exchanged for ready money; ours are to be exchanged in the same manner. In short, the plans are the same, one copied from the other, identical in design, in structure, and in mode of operation; and wherein they differ (as they do in some details), the advantage is on the side of the British. For example: 1. The British pay interest on their bills, and raise the interest when necessary to sustain them in the market. Ours are to pay no interest, and will depreciate from the day they issue. 2. The British cancel and destroy their bills when once paid: we are to reissue ours, like common bank notes, until worn out with use. 3. The British make no small bills; none less than £100 sterling ($500), we begin with five dollars, like the old continentals; and, like them, will soon be down to one dollar, and to a shilling. 4. The British board could issue no bill except as specially authorized from time to time by act of Parliament: ours is to keep out a perpetual issue of fifteen millions; thus creating a perpetual debt to that amount. 5. The British board was to have no deposit of government stocks: ours are to have a deposit of five millions, to be converted into money when needed, and to constitute another permanent debt to that amount. 6. The British gave a true title to their exchequer act: we give a false one to ours. They entitled theirs, "An act for regulating the issuing and paying off, of exchequer bills:" we entitle ours, "A bill amendatory of the several acts establishing the Treasury department." In these and a few other particulars the two exchequers differ; but in all the essential features – design – structure – operation – they are the same.

Having shown that our proposed exchequer was a copy of the British system, and that we are having recourse to it under the same circumstances: that in both countries it is a transit from corporation credit deceased, to government credit which is to bear the brunt of new follies and new extravagances: having shown this, I next propose to show the manner in which this exchequer system has worked in England, that, from its workings there, we may judge of its workings here. This is readily done. Some dates and figures will accomplish the task, and enlighten our understandings on a point so important. I say some dates and figures will do it. Thus: at the commencement of this system in England the annual taxes were 5 millions sterling: they are now 50 millions. The public debt was then 40 millions: it is now 900 millions, the unfunded items included. The interest and management of the debt were then 11⁄2 millions: they are now 30 millions.

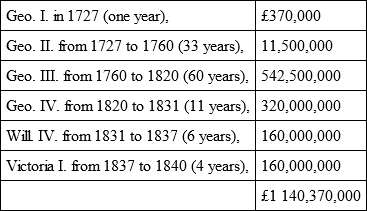

Here Mr. B. exhibited a book – the index to the British Statutes at large – containing a reference to all the issues of exchequer bills from the last year of the reign of George I. (1727) to the fourth year of the reign of her present Majesty (1840). He showed the amounts issued under each reign, and the parallel growth of the national debt, until these issues exceeded a thousand millions, and the debt, after all payments made upon it, is still near one thousand millions. Mr. B. here pointed out the annual issues under each reign, and then the totals for each reign, showing that the issues were small and far between in the beginning – large and close together in the conclusion – and that it was now going on faster than ever.

The following was the table of the issues under each reign:

Near twelve hundred millions of pounds sterling in less than a century and a quarter – we may say three-quarters of a century, for the great mass of the issues have taken place since the beginning of the reign of George III. The first issue was the third of a million; under George II., the average annual issue was the third of a million; under George III., the annual average was nine millions; under George IV. it was thirty millions; under William IV. twenty-three millions; and under Victoria, it is twenty-one millions. Such is the progress of the system – such the danger of commencing the issue of paper money to supply the wants of a government.

This, continued Mr. B., is the fruit of the exchequer issues in England, and it shows both the rapid growth and dangerous perversion of such issues. The first bills of this kind ever issued in that country were under William III., commonly called the Prince of Orange, in the year 1696. They were issued to supply the place temporarily of the coin, which was all called in to be recoined under the superintendence of Sir Isaac Newton. The first bills were put out by King William only for this temporary purpose, and were issued as low as ten pounds and five pounds sterling. It was not until more than thirty years afterwards, and when corporation credit had failed, that Sir Robert Walpole revived the idea of these bills, and perverted them into a currency, and into instruments for raising money for the service of the government. His practice was to issue these bills to supply present wants, instead of laying taxes or making a fair and open loan. When due, a new issue took up the old issue; and when the quantity would become great, the whole were funded; that is to say saddled upon posterity. The fruit of the system is seen in the 900,000,000 of debt which Great Britain still owes, after all the payments made upon it. The amount is enormous, overwhelming, appalling; such as never could have been created under any system of taxes or loans. In the nature of things government expenditure has its limits when it has to proceed upon taxation or borrowing. Taxes have their limit in the capacity of the people to pay: loans have their limit in the capacity of men to lend; and both have their restraints in the responsibility and publicity of the operation. Taxes cannot be laid without exciting the inquiry of the people. Loans cannot be made without their demanding wherefore. Money, i. e. gold and silver, cannot be obtained, but in limited and reasonable amounts, and all these restraints impose limits upon the amount of government expenditure and government debt. Not so with the noiseless, insidious, boundless progress of debt and expenditure upon the issue of government paper! The silent working of the press is unheard heard by the people. Whether it is one million or twenty millions that is struck, is all one to them. When the time comes for payment, the silent operation of the funding system succeeds to the silent operation of the printing press; and thus extravagant expenditures go on – a mountain of debt grows up – devouring interest accrues – and the whole is thrown upon posterity, to crush succeeding ages, after demoralizing the age which contracted it.

The British debt is the fruit of the exchequer system in Great Britain, the same that we are now urged to adopt, and under the same circumstances; and frightful as is its amount, that is only one branch – one part of the fruit – of the iniquitous and nefarious system. Other parts remain to be stated, and the first that I name is, that a large part of this enormous debt is wholly false and factitious! McCulloch states two-fifths to be fictitious; other writers say more; but his authority is the highest, and I prefer to go by it. In his commercial dictionary, now on my table, under the word "funds," he shows the means by which a stock for £100 would be granted when only £60 or £70 were paid for it; and goes on to say:

"In consequence of this practice, the principal of the debt now existing amounts to nearly two-fifths more than the amount actually advanced by the lender."

So that the English people are bound for two-fifths more of capital, and pay two-fifths more of annual interest, on account of their debt than they ever received. Two-fifths of 900,000,000 is 360,000,000; and two-fifths of 30,000,000 is 12,000,000; so that here is fictitious debt to the amount of $1,600,000,000 of our money, drawing $60,000,000 of interest, for which the people of England never received a cent; and into which they were juggled and cheated by the frauds and villanies of the exchequer and funding systems! those systems which we are now unanimously invited by our administration to adopt. The next fruit of this system is that of the kind of money, as it was called, which was considered lent, and which goes to make up the three-fifths of the debt admitted to have been received; about the one-half of it was received in depreciated paper during the long bank suspension which took place from 1797 to 1823, and during which time the depreciation sunk as low as 30 per centum. Here, then, is another deduction of near one-third to be taken off the one-half of the three-fifths which is counted as having been advanced by the lenders. Finally, another bitter drop is found in this cup of indebtedness, that the lenders were mostly jobbers and gamblers in stocks, without a shilling of their own to go upon, and who by the tricks of the system became the creditors of the government for millions. These gentry would puff the stocks which they had received – sell them at some advance – and then lend the government a part of its own money. These are the lenders – these the receivers of thirty millions sterling of taxes – these the scrip nobility who cast the hereditary nobles into the shade, and who hold tributary to themselves all the property and all the productive industry of the British empire. And this is the state of things which our administration now proposes for our imitation.

This is the way the exchequer and funding system have worked in England; and let no one say they will not work in the same manner in our own country. The system is the same in all countries, and will work alike every where. Go into it, and we shall have every fruit of the system which the English people now have; and of this most of our young States, and of our cities, and corporations, which have gone into the borrowing business upon their bonds, are now living examples. Their bonds were their exchequer bills. They used them profusely, extravagantly, madly, as all paper credit is used. Their bonds were sold under par, though the discount was usually hid by a trick: pay was often received in depreciated paper. Sharpers frequently made the purchase, who had nothing to pay but a part of the proceeds of the same bonds when sold. And thus the States and cities are bound for debts which are in a great degree fictitious, and are bound to lenders who had nothing to lend; and such are the frauds of the system which is presented to us, and must be our fate, if we go into the exchequer system.

I have shown the effect of an exchequer of issues in Great Britain to strike paper money for a currency, and as a substitute for loans and taxes. I have shown that this system, adopted by Sir Robert Walpole upon the failure of corporation credit, has been the means of smuggling a mountain load of debt upon the British people, two-fifths of which is fraudulent and fictitious; that it has made the great body of the people tributaries to a handful of fundholders, most of whom, without owning a shilling, were enabled by the frauds of the paper system and the funding system, to lend millions to the government. I have shown that this system, thus ruinous in England, was the resort of a crafty minister to substitute government credit for the exhausted credit of the moneyed corporations, and the exploded bubbles; and I have shown that the exchequer plan now presented to us by our administration, is a faithful copy of the English original. I have shown all this; and now the question is, shall we adopt this copy? This is the question; and the consideration of it implies the humiliating conclusion, that we have forgot that we have a constitution, and we have gone back to the worst era of English history – to times of the South Sea bubble, to take lessons in the science of political economy. Sir, we have a Constitution! and if there was any thing better established than another, at the time of its adoption, it was that the new government was a hard-money government, made by hard-money men, who had seen and felt the evils of government paper, and who intended for ever to cut off the new government from the use of that dangerous expedient. The question was made in the Convention (for there was a small paper money party in that body), and solemnly decided that the government should not emit paper money, bills of credit, or paper currency of any kind. It appears from the history of the Convention, that the first draft of the constitution contained a paper clause, and that it stood in connection with the power to raise money; thus: "To borrow money, and emit bills, on the credit of the United States." When this clause came up for consideration, Mr. Gouverneur Morris moved to strike out the words, "and emit bills," and was seconded by Mr. Pierce Butler. "Mr. Madison thought it sufficient to prevent them from being made a tender." "Mr. Ellsworth thought this a favorable moment to shut and bar the door against paper money. The mischief of the various experiments which had been made, were now fresh in the public mind, and had excited the disgust of all the respectable part of America. By withholding the power from the new government, more friends of influence would be gained to it than by almost any thing else. Paper money can in no case be necessary. Give the government credit, and other resources will offer. The power may do harm, never good." Mr. Wilson said: "It will have a most salutary influence on the credit of the United States, to remove the possibility of paper money. This expedient can never succeed while its mischiefs are remembered; and as long as it can be resorted to, it will be a bar to other resources." "Mr. Butler remarked that paper was a legal tender in no country in Europe. He was urgent for disarming the government of such a power." "Mr. Read thought the words, if not struck out, would be as alarming as the mark of the beast in Revelations." "Mr. Langdon had rather reject the whole plan than retain the three words, 'and emit bills.'" A few members spoke in favor of retaining the clause; but, on taking the vote, the sense of the convention was almost unanimously against it. Nine States voted for striking out: two for retaining.