полная версия

полная версияA Girl's Ride in Iceland

The next morning, as soon as we had breakfasted, we mounted our ponies with the regretful feeling the day's ride would be our last in Iceland. We had been unfortunate in missing the clergyman at Thingvalla both going and returning: we regretted it the more as we heard that he was a very clever man and a good English scholar. Our good-natured hostess, however, had done her best to supply his place, and we bade her a hearty farewell, with much shaking of hands. Off we went at a gallop, traversing the same route, fording the same rivers as on our up journey, arriving safely at Reykjavik on the fourth day from that on which we had left it, having compassed the 160 miles in three and a half days with comparatively little fatigue, which I attribute to our mode of riding being so much easier a movement than sitting sideways with a half twisted body. I can only repeat what I before said, that we should never have accomplished this long and fatiguing ride so easily, and in such a short time, either in a chair or on a side saddle; so if any lady should follow our example, and go to Iceland, let her be prepared to defy Mrs Grundy, and ride as a man.

We had certainly every reason to be contented with the result of our trip to the Geysers. The weather had been favourable, – very hot sometimes in the middle of the day, but cold at night; but this was rather refreshing than otherwise, and the scenery had well repaid our toil and trouble. The Icelandic landscapes do not lack colour, as has been asserted by some travellers; whilst the clearness of the atmosphere is wonderful, and the shades of blue, purple, carmine, and yellow in the sky melting into one another produce most lovely effects.

Unquestionably the landscape lacks trees and verdure, and one missed the gorgeous autumn colouring of our English woods, for there is no foliage, only low scrub jungle. It seems very doubtful if Iceland was ever wooded, as is supposed by some persons, as no trees of any size have as yet been discovered in the peat beds, a very conclusive evidence to the contrary.

Iceland is so sparsely populated that one often rides miles without encountering a human being. Even in the little town of Sauderkrok there is not much life in the streets; for instance, A. L. T. dropped his pipe as we rode out of the town, and on our return, eight hours later, we found it in the centre of a small street, exactly where he had dropped it. Now, as a pipe is a coveted luxury to an Icelander, it is presumable that no one could have passed along that street in our absence.

It was just 3 p. m. when we entered Reykjavik, having accomplished our last day's ride from Thingvalla in six and a half hours. The Camoens was still safely at anchor in the harbour, and we rejoiced at having returned without a single contretemps.

On our way through Reykjavik to the ship Mr Gordon ordered dinner at the hotel to be ready by 7 o'clock, and we looked forward to this repast with much pleasure after our tinned meat and biscuit diet of the last few days.

Before returning on board to change our riding dresses, we went in search of the washing. In a queer little wooden house, at the back of the town, we found the washerman, who smiled and nodded, and asked 3s. for what would have cost 30s. in England, handing us an enormous linen bag, in which the things were packed. This was consigned to A. L. T., who carried it in both arms through the town, and ultimately on board, where it landed quite dry; and to our surprise we found our linen had been most beautifully washed and got up, quite worthy of a first-class laundry.

The dinner was excellent, everything being very hot, and served in Danish style. As is the universal custom among the better class, the hostess waited on us herself, and told us she had spun her own dress and the sitting-room carpet the winter before, and always wove her own linen. This was our last evening ashore, as we were to heave anchor at midnight on Tuesday, 17th August, and in four and a half days we were, if all went well, to find ourselves back in Scotland. Alas! these expectations were not realised, as few human aspirations are!

During our four days' absence to the Geysers, the captain and crew had been engaged in shipping no less than 617 ponies, which additional cargo caused two days' delay. Poor little beasts, when we arrived on board we found they had all been so tightly stowed away as not to be able to lie down. Fine sturdy little animals they appeared, mostly under seven years of age, and in excellent condition; a very different sight to what they were on arriving at Granton, when, after six and a half days' voyage, every rib showed distinctly through their wasted, tucked up forms.

After our dinner we lounged about in Reykjavik, paying a farewell visit to the few objects of interest it has for travellers, most of which have already been cursorily noticed in a previous chapter.

We spent some little time in the Museum again, which, after all, is not much of an exhibition, for, as our cicerone, the hotel-keeper's daughter, Fräulein Johannison, explained, all the best curiosities had been carried off to Denmark. I naturally looked everywhere in the little Museum for an egg of the Great Auk, or a stuffed specimen of the bird, but there was neither, which struck me as rather curious, considering Iceland was originally the home of this now extinct species. Not even an egg has been found for over forty years, although diligent search has been made by several well-known naturalists. The Great Auk was never a pretty bird; it was large in size, often weighing 11 lb. It had a duck's bill, and small eyes, with a large unwieldy body, and web feet. Its wings were extremely small and ugly, from long want of use, so the bird's movements on land were slow, and it was quite incapable of flight. On the water it swam fast and well.

There are only about ten complete specimens of this bird, and about seventy eggs, known to exist In March 1888, one of these eggs was sold by auction for £225.

From the Museum we entered some of the stores, and purchased a fair collection of photographs, some skin shoes, snuff-boxes, buckles, and other native curios; we than returned to the hotel, paid our bill, bade our host, hostess, and guides farewell, with many regretful shakes of the hand on either side, and finally quitted Icelandic ground about 9 p. m.

The evening was lovely, and after arranging our cabins we remained some time on deck watching the Northern Lights, which illuminated the entire heavens, and were most beautiful. Unfortunately we did not see the 'Aurora Borealis,' which in these latitudes is often visible.

The following afternoon as we were passing the curious rocky Westmann Islands, we slacked steam, to allow an old man in a boat to get the mail bag thrown over to him. He had rowed out some three miles to fetch the mail, and the bag contained exactly one letter, and a few newspapers. Steaming on again we sighted no more land until Scotland came in view, which we reached on Sunday afternoon. What a passage we had! It was rough going to Iceland, but nothing to be compared to our return voyage! We sat on deck, either with our chairs lashed, or else holding on to ropes until our hands were quite benumbed with cold, while huge waves, at least 15 feet high, dashed over the ship, often over the bridge itself. If we opened our cabin portholes for a little fresh air, which at times was really a necessity, the cabin was soon flooded, and our clothes and rugs spent half their time being dried in the donkey engine room.

Eleven of the poor ponies died, and had to be thrown overboard, a serious loss to their owners; but one could not help wondering that more of them did not succumb, so closely were they packed together, with very little air but that afforded by the windsails. It was marvellous how the sailors managed to drag out the dead from the living mass of animals. This they accomplished by walking on the backs of the survivors, and roping the dead animals, drew the carcases to the centre hold of the ship, when the crane soon brought them to the surface, and consigned them to a watery grave.

For six days the live cargo of beasts had to balance themselves with the ship's movement in these turbulent seas without one moment's respite or change of position. No wonder that on arriving at Granton they were in a miserable plight. Within five minutes, however, of our being roped to the pier they were being taken off in horse boxes, three at a time, and the entire number were landed in three hours.

The hot air from the stables was at times overpowering, notwithstanding that eight windsails were kept over it, which as they flapped in the wind, looked just like eight ghosts.

The Camoens was a steady sea boat, but better adapted for cargo than for passengers, especially lady passengers, and the captain did not disguise that he preferred not having the latter on board. Once in calm water we discovered we had seriously shifted our cargo, and lay all over on one side, so much so that a cup of tea could not stand, the slant being great, although the water was perfectly calm.

Well, we had accomplished our trip, and very much we had enjoyed it. We had really seen Iceland, that far off region of ice and snow, and had returned safely. The six days on board ship passed pleasantly enough for us; we had got accustomed to roughing it, and were all very good friends with each other, and the few other passengers. We found one of these especially interesting; he was a scientific Frenchman, who had been sent to Iceland to write a book for the Government, and being a very poor English scholar was very glad to find some one who could converse in his native tongue. We hardly saw a ship the whole way, but we saw plenty of whales, not, however, the kind which go to Dundee, where the whalebone fetches from £1200 to £2000 a ton.

We brought an enormous skeleton home which was found off the coast of Iceland; and such an immense size; it was sent to England as a curiosity for some museum.

Occasionally we had lovely phosphorescent effects, and as we neared Scotland, millions of pink and brown jelly-fish filled the water. At Thurso we hailed a boat to send telegrams ashore – such a collection! – to let our various friends know we had returned in safety from Ultima Thule. That night as we passed Aberdeen we entered calm water, and there was hardly a ripple all the way to Granton, where we landed at 3.30 on Monday, 23d August, exactly twenty-four days from starting.

Such a lovely day! The Forth looked perfect as we steamed up to our harbour anchorage. The grand hills and rocks and the fine old Castle were a contrast to poor little Reykjavik, the capital of Iceland. The pretty town, and the trees, how we enjoyed the sight of the latter, for we had seen no trees for weeks, and their green looked most pleasing amongst the stone buildings.

How busy, how civilised everything appeared! When will trains and carts traverse the Northern Isle we had just left? Oh, but where are the emigrants? Let us go and watch their surprised faces as they catch the first glimpse of this new scene. We went, and were sorely disappointed. They were merely standing together with their backs to the view, putting on their boots, or occupied about minor matters, taking no notice whatever of their surroundings, and receiving no new impressions. It must require a civilised mind, we suppose, to appreciate civilisation, just as it requires talent to appreciate talent.

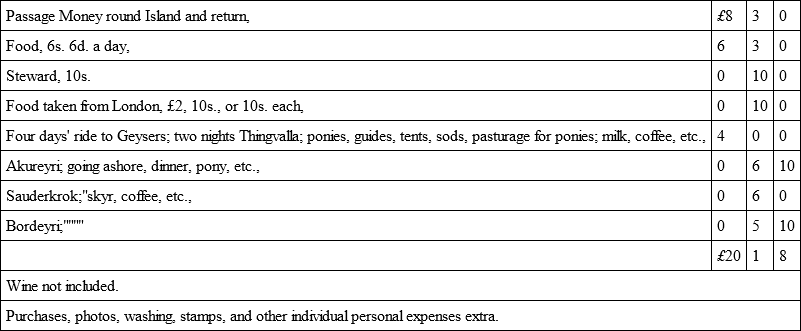

Below is a table of our expenditure during our trip, which may perhaps prove of service to one wishing to enjoy an uncommon autumn holiday: —

Five people travelling together for twenty-five days disbursed each £20, 1s. 8d.

CHAPTER XII.

VOLCANOES

In the foregoing pages it may seem strange that hardly any allusion has been made to the special characteristic of Iceland, viz., its volcanic structure, or to the numerous lava floods which, bursting forth in furious molten streams, have from time to time devastated its surface, leaving in their track a chaos of disrupted rocks, chasms, vast fissures, and subterranean caverns.

Our trip to Iceland was, however, unfortunately so limited in duration as to preclude, save in our four days' ride to the Great Geyser tract, any extension of travel in the various volcanic regions. Hence the omission. I have therefore extracted the following data relative to its principal volcanoes and their eruptions from such books of reference1 as have been available to me.

The annexed compilation will, I think, explain to such of my readers as are not acquainted with the geological strata of Iceland, its sterile nature, the extreme poverty of its inhabitants, and the constant terror under which their existence is passed, lest a fresh outbreak of lava should sweep away both them and their homesteads. It is somewhat singular, that although Iceland may be looked upon as a veritable mass of volcanoes and hot springs – for with the exception of some 4000 square miles of habitable ground, it may be said literally to rest on underground fires, and while the various eruptions of Etna, Vesuvius, and other volcanoes have for centuries been watched and recorded in the public papers with interest – it is only comparatively recently that the awe-inspiring volcanic eruptions of Iceland have been brought into notice. For instance, while full fifty pages in Ree's 'Cyclopædia' are devoted to the subject of volcanoes, those of Iceland are barely touched upon; yet their eruptions are by far the most devastating on record. So limited, indeed, formerly were the researches of science in these ice-clad regions, that for long Hecla was quoted as its only volcano.

Now that the Island has attracted the further notice of geologists, it has been shown that there exist no less than twenty volcanic mountains, all of which have been in active eruption within historic times, and nearly one hundred eruptions have been chronicled as having taken place in the Island.

Although Hecla is doubtless the best known of the Iceland volcanoes, it is by no means the largest; that of 'Askja' (a basket), far surpasses it in size. This latter volcano lies in a great central desert termed 'Odaxa-hraun' or 'Misdeed Lava Desert,' covering a space of 1200 square miles, and a most appropriate name it is, for the devastation caused by its last flood of lava is indescribable.

In one of the convulsions of this mountain in 1875, a quantity of lava five miles in circumference was disrupted, sinking into the mountain to a depth of 710 feet, and causing an earthquake which was felt all over the island. In one region, viz., that of the 'Myvatn's Orœfi' or 'Midge Lake Desert,' a fissure was opened which extended over 20 miles in a north-easterly direction, through which molten lava flowed continuously for four months after the earthquake. Although this fissure is at least 30 miles from Askja, so great was the column of fire thrown up by the eruption, that it was visible for four successive days at Reykjavik, 100 miles distant. The study of an Icelandic map will show the numerous volcanic ranges of mountains which intersect the island in almost every direction.

To the north there will be seen a wonderful volcanic tract. So vast, in fact, that Professor Johnstrup has termed it the Fire Focus of the North. To the north-east, again, is found a large lake, called 'Myvata,' or 'Midge Lake,' with a volcanic range of mountains which stretch from north to south; the most famous of these are 'Leivhnukr,' and 'Krafla,' which, after years of quiescence, poured forth such an amount of lava into the adjoining lake that for many days its waters stood at boiling heat. Other volcanoes in this region eject with terrible force a quantity of boiling mineral pitch, throwing up the dark matter completely enveloped in steam, accompanied by horrible rumbling noises.

Sir George Mackenzie, in his travels in Iceland, thus describes one of the deposits: —

'It is impossible,' he says, 'to convey any idea of the wonders of its terrors, or the sensations of a person even of strong nerves standing on a support which but feebly bears him, and below which fire and brimstone are in incessant action, having before his eyes tremendous proof of what is going on beneath him; enveloped in thick vapour, his ears stunned with thundering noises – such a situation can only be conceived by one who has experienced it.'

The extent of the sulphur beds too in this region are beyond calculation: they reproduce themselves every few years. In the vicinity of 'Krafla' is a curious rock, composed of obsidian, a substance which closely resembles black glass.

To the south of the Island is another volcano, termed the 'Kotlugja,' or 'Cauldron Rift,' lying among glaciers known as the 'Myrdals Jökull,' whose eruptions, thirteen of which have been noted, are considered to have done more mischief than any others in the Island. Between the Myrdals and the 'Orœja Jökla' lies one of the most noted volcanoes of Iceland – the 'Skaptar-Jökull,' whose eruption in 1783 is chronicled in all works on Iceland, as the prodigious floods of lava it poured forth in that year were unparalleled in historic times. The molten streams rushing seaward, down the rivers and valleys, the glowing lava leaping over precipices and rocks, which in after years, when they have cooled down, resemble petrified cataracts, and now form one of the grand scenic attractions of the Island.

In Mrs Somerville's 'Physical Geography,' she vividly describes this eruption, narrating how, commencing in May 1783, it continued pouring forth its fiery streams with unabated fury until the following August. So great was the amount of vapour, that the sun was hidden for months, whilst clouds of ashes were carried hundreds of miles out to sea. The quantity of matter ejected on this occasion was calculated at from fifty to sixty thousand millions of cubic yards. The burning lava flowed in a stream in some places 20 to 30 miles broad, filling up the beds of rivers, and entering the sea at a distance of 50 miles from where the eruption occurred. Some of the rivers were not only heated to boiling point, but were dried up, and the condensed vapour fell as snow and rain. Epidemic disease followed in the wake of this fearful lava flood. It was calculated that no less than 1300 persons, and 150,000 sheep and cattle perished, 20 villages were destroyed. The eruption lasted two years.

Mr Paulson, a geologist, who visited Iceland eleven years later, found smoke still issuing from the rocks in the locality.

The heat of this eruption not only re-melted old lavas, and opened fresh subterranean caverns, but one of its streams was computed to course the plains to an extent of 50 miles, with a depth of 100 feet, and 12 to 15 feet broad. Another stream was calculated at 40 miles long, and 7 wide. Men, their cattle and homesteads, their churches and grazing lands, were burnt up, whilst noxious vapours not only filled the air, but even shrouded the light of the sun.

The terrible convulsions which occurred in Iceland during the year 1783, were greater than those recorded at any other period. About a month previously to the convulsion of 'Skaptar-Jökull,' a submarine volcano burst out at sea, and so much pumice stone was ejected that the sea was covered with it for 150 miles round, ships being stopped in their course, whilst a new island was thrown up, which the King of Denmark claimed, and named Nyöe, or New Island. Before the year had elapsed, however, it as speedily disappeared, leaving only a reef of rocks some 30 fathoms under water to mark its site.

But what of Hecla? which is 5000 feet high, and is situated close to the coast at the Southern end of a low valley, lying between two vast parallel table lands covered with ice.

If the eruptions of Hecla are not considered to have been quite so devastating as those just recorded of the 'Skaptar-Jökull,' their duration has been longer, some of them having lasted six years at a time.

When Sir George Mackenzie visited Hecla, he found its principal crater 100 feet deep, and curiously enough, it contained a quantity of snow at the bottom. There are many smaller craters near its summit, the surrounding rocks, consisting chiefly of lava and basalt, are covered with loose stones, scoria, and ashes.

A record of the eruptions of Hecla has been chronicled since the 10th century, and they number 43. One of its most violent convulsions occurred in the same year as that of the 'Skaptar-Jökull,' viz., in 1783. At a distance of two miles from the crater, the lava flood was one mile wide, and 40 feet deep, whilst its fine dust was scattered as far as the Orkney Islands, 400 miles distant.

The mountain itself is composed of sand, grit, and ashes, several kinds of pumice stone being thrown out of it. It also ejects a quantity of a species of black jaspars, which look as if they had been burned at the extremities, while in form they resemble trees and branches. All the different kinds of lava found in volcanoes are to be met with here, such as agate, pumice stone, and both black and green lapis obsidian. These lavas are not all found near the place of eruption, but at some distance, and on their becoming cold form arches and caverns, the crust of which being hard rock. The smaller of the caverns are now used by the Icelanders for sheltering their cattle. The largest of the caves known is 5034 feet long and from 50 to 54 feet broad and from 34 to 36 feet high.

It is believed by some geologists that a subterranean channel connects the volcanic vent of Hecla with the great central one of Askja. This theory is based on the fact that a number of lava floods have burst forth simultaneously at different times at great distances from the volcanoes, leading to the supposition that innumerable subterranean channels exist in the neighbourhood.

The eruptions attributed to the volcano of Hecla vary much in number, some authorities saying there have been 40. Mrs Somerville quotes them at 23, and Mr Locke, in his 'Guide to Iceland,' at 17 in number. In the latter's work is given a table of most of its principal eruptions. One of these was of a singular nature; huge chasms opened in the earth, and for three days the wells and fountains became as white as milk, and new hot springs sprang into existence.

The twelfth eruption of this mountain was also of unusual violence. It occurred in January 1597. For twelve days previously to the outbreak loud reports were heard all over the Island, while no less than eighteen columns of fire were seen ascending from it during its eruption. The ashes it threw out covered half the Island.

The seventeenth eruption commenced on the 2d September 1845, and continued for seven months. On this occasion the ashes were carried over to Shetland, and the columns of smoke rising from the mountain reached a height of 14,000 Danish feet.

Such is a brief description of the tremendous forces which dominate Iceland. Here Nature works in silence for long periods beneath the crust of the earth, and then, with little or no forewarning, bursts forth in uncontrollable fury, ruthlessly devastating with its fiery streams whatever impedes its course.

Who can wonder that, under such existing terrors, the scanty inhabitants of the Island are a sad and dejected race. A people with death and terror continually at their doors can hardly be otherwise; whilst competitive industry, energy, and hopeful prosperity are alike suppressed by the constant devastations which occur.

With respect to the Thermal Springs, these must be considered as products of the same underground fires, and which form a second characteristic of Iceland.

These Springs may be divided into three kinds, viz., those of unceasing ebullition, those which are only sometimes eruptive, and wells which merely contain tepid water, though supposed to have been formerly eruptive.

Professor Bunsen, who passed eleven days by the side of the Great Geyser in Iceland, attributes the phenomenon to the molecular changes which take place in water after being subjected to heat. In such circumstances, water loses much of the air condensed in it, and the cohesion of the molecules is thereby increased, and a higher temperature required to boil it. In this state, when boiled, the production of vapour is so instantaneous as to cause an explosion.

Professor Bunsen found that the water at the bottom of the great Icelandic Geyser had a higher temperature than that of boiling water, and that this temperature increasing, finally caused its eruption.