полная версия

полная версияThe White Prophet, Volume I (of 2)

Without more ado Gordon took her firmly in his arms, and with one hand on her forehead that he might look full in her face, he said —

"You are not angry with me, Helena – for what I said to your father just now?"

"No, oh no! you were speaking out of your heart, and perhaps it was partly that – "

"You didn't agree with me, I know that quite well, but you love me still, Helena?"

"Don't ask me that, dear."

"I must. I am going away, so speak out, I entreat you. You love me still, Helena?"

"I am here. Isn't that enough?" she said, putting her arms about his neck and laying her head on his breast.

He kissed her, and there was silence for some moments more. Then in a sharp, agitated whisper she said —

"Gordon, that man is coming between us."

"Ishmael Ameer?"

"Yes."

"What utter absurdity, Helena!"

"No, I'm telling you the truth. That man is coming between us. I know it – I feel it – something is speaking to me – warning me. Listen! Last night I saw it in a dream. I cannot remember what happened but he was there, and you and I, and your father and mine, and then – "

"My dear Nell, how foolish! But I see what has happened. When did you receive the Princess Nazimah's letter?"

"Last night – just before going to bed."

"Exactly! And you were brooding over what she said of the needle carrying only one thread?"

"I was thinking of it – yes."

"You were also thinking of what you had said yourself in your letter to me – that if I resisted my father's will the results might be serious for all of us?"

"That too, perhaps."

"There you are, then – there's the stuff of your dream, dear. But don't you see that whatever a man's opinions and sympathies may be, his affections are a different matter altogether – that love is above everything else in a man's life – yes, everything – and that even if this Ishmael Ameer were to divide me from my father or from your father – which God forbid! – he could not possibly separate me from you?"

She looked up into his eyes and said – there was a smile on her lips now – "Could nothing separate you and me?"

"Nothing in this world," he answered.

Her trembling lips fluttered up to his, and again there was a moment of silence. The sun had gone down, the stars had begun to appear, and, under the mellow gold of mingled night and day, the city below, lying in the midst of the desert, looked like a great jewel on the soft bosom of the world.

"You must go now, dear," she whispered.

"And you will promise me never to think these ugly thoughts again?"

"'Love is above everything' – I shall only think of that. Good-bye!"

"Good-bye!" he said, and he embraced her passionately. At the next moment he was gone.

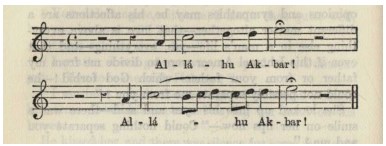

Shadows from the wing of night had gathered over the city by this time, and there came up from the heart of it a surge of indistinguishable voices, some faint and far away, some near and loud, the voices of the muezzins calling from a thousand minarets to evening prayers – and then came another voice from the glistening crest of the great mosque on the ramparts, clear as a clarion and winging its way through the upper air over the darkening mass below —

"God is Most Great! God is Most Great!"

Music fragment

CHAPTER XII

At half-past six Gordon was at the railway-station. He found his soldier servant half-way down the platform, on which blue-shirted porters bustled to and fro, holding open the door of a compartment labelled "Reserved." He found Hafiz also, and with him were two pale-faced Egyptians, in the dress of Sheikhs, who touched their foreheads as Gordon approached.

"These are the men you asked for," said Hafiz.

Gordon shook hands with the Egyptians, and then standing between them, with one firm hand on the shoulder of each and the light of an electric arc lamp in their faces, he said —

"You know what you've got to do, brothers?"

"We know," the men answered.

"The future of Egypt, perhaps of the East, may depend upon what you tell me – you will tell me the truth?"

"We will tell you the truth, Colonel."

"If the man we are going to see should be condemned on your report and on my denunciation you may suffer at the hands of his followers. Protect you as I please, you may be discovered, followed, tracked down – you have no fear of the consequences?"

"We have no fear, sir."

"You are prepared to follow me into any danger?"

"Into any danger."

"To death if need be?"

"To death if need be, brother."

"Step in, then," said Gordon.

At the next moment there was the whistle of the locomotive, and then slowly, rhythmically, with its heavy volcanic throb shaking the platform and rumbling in the glass roof, the train moved out of the station on its way to Alexandria.

CHAPTER XIII

Ishmael Ameer was the son of a Libyan carpenter and boat-builder who, shortly before the days of the Mahdi, had removed with his family to Khartoum. His earliest memory was of the solitary figure of the great white Pasha, on the roof of the palace, looking up the Nile for the relief army that never arrived, and of the same white-headed Englishman, with the pale face, who, walking to and fro on the sands outside the palace garden, patted his head and smiled.

His next memory was of the morning after the fall of the desert city, when, awakened by the melancholy moan of the great ombeya, the elephant-horn that was the trumpet of death, he heard the hellish shrieks of the massacre that was going on in the streets, and saw his mother lying dead in front of the door of the inner closet in which she had hidden him, and found his father's body on the outer threshold.

He was seven years of age at this time, and being adopted by an uncle, a merchant in the town who had been rich enough to buy his own life, he was sent in due course first to the little school of the mosque in Khartoum, and afterwards, at eighteen, to El Azhar in Cairo, where, with other poor students, he slept in the stifling rooms under the flat roof and lived on the hard bread and the jars of cheese and butter which were sent to him from home.

Within four years he had passed the highest examination at the Arabic University, taking the rank of Alim (doctor of Koranic divinity), which entitled him to teach and preach in any quarter of the Mohammedan world, and then, by reason of his rich voice and his devout mind, he was made Reader in the mosque of El Azhar.

Morality was low among the governing classes at that period, and when it occurred that the Grand Cadi, who was a compound of the Eastern voluptuary and the libertine of the Parisian boulevards, marrying for the fourth time, made a feast that went on for a week, in which the days were spent in eating and drinking and the nights in carousing of an unsaintly character, the orgy so shocked the young Alim from the desert that he went down to the great man's house to protest.

"How is this, your Eminence?" he said stoutly. "The Koran teaches temperance, chastity, and contempt of the things of the world, yet you, who are a tower and a light in Islam, have darkened our faces before the infidel."

So daring an outrage on the authority of the Cadi had never been committed before, and Ishmael was promptly flung into the streets, but the matter made some noise, and led in the end to the expulsion of all the Governors (the Ulema) of the University except the one man who, being the first cause of the scandal, was also the representative of the Sultan, and therefore could not be charged.

Meantime Ishmael, returning no more to El Azhar, had settled himself on an island far up the river, and there practising extreme austerities, he gathered a great reputation for holiness, and attracted attention throughout the valley of the Nile by breathing out threatening and slaughter, not so much against the leaders of his own people who were degrading Islam as against the Christians, under whose hated bondage, as he believed, the whole Mohammedan world was going mad.

So wide was the appeal of Ishmael's impeachment and so vast became his following that the Government (now Anglo-Egyptian), always sure that, after sand-storms and sand-flies, holy men of all sorts were the most pernicious products of the Soudan, thought it necessary to put him down, and for this purpose they sent two companies of Arab camel police, promising a reward to the one that should capture the new prophet.

The two camel corps set out on different tracks, but each resolving to take Ishmael by night, they entered his village at the same time from opposite ends, met in the darkness, and fought and destroyed one another, so that when morning dawned they saw their leaders on both sides lying dead in the crimsoning light.

The gruesome incident had the effect of the supernatural on the Arab intellect, and when Ishmael and his followers, with nothing but a stick in one hand and the Koran in the other, came down with a roar of voices and the sand whirling in the wind, the native remnant turned tail and fled before the young prophet's face.

Then the Governor-General, an agnostic with a contempt for "mystic senses" of all kinds, sent a ruckling, swearing, unbelieving company of British infantry, and they took Ishmael without further trouble, brought him up to Khartoum, put him on trial for plotting against the Christian Governor of his province, and imprisoned him in a compound outside the town.

But soon the Government began to see that though they had crushed Ishmael they could not crush Ishmaelism, and they lent an ear to certain of the leaders of his own faith, judges of the Mohammedan law courts, who, having put their heads together, had devised a scheme to wean him from his asceticism, and so destroy the movement by destroying the man. The scheme was an old one, the vales of a woman, and they knew the very woman for the purpose.

This was a girl named Adila, a Copt, only twenty years of age, and by no means a voluptuous creature, but a little winsome thing, very sweet and feminine, always freshly clad, and walking barefoot on the hot sand with an erect confidence that was beautiful to see.

Adila had been the daughter of a Christian merchant at Assouan, and there, six years before, she had been kidnapped by a Bisharin tribe, who, answering her tears with rough comfort, promised to make her a queen.

In their own way they did so, for those being the dark days of Mahdism, they brought her to Omdurman and put her up to auction in the open slave-market, where the black eunuch of the Caliph, after thrusting his yellow fingers into her mouth to examine her teeth, bought her, among other girls, for his master's harem.

There, with forty women of varying ages, gathered by concupiscence from all quarters of the Soudan, she was mewed up in the close atmosphere of two sealed chambers in the Caliph's crudely gorgeous palace, seeing no more of her owner than his coffee-coloured countenance as he passed once a day through the curtained rooms and signalled to one or other of their bedecked and be-ringleted occupants to follow him down a hidden stairway to his private quarters. At such moments of inspection Adila would sit trembling and breathless, in dread of being seen, and she found her companions only too happy to help her to hide herself from the attentions they were seeking for themselves.

This lasted nearly a year, and then came a day when the howling in the streets outside, the wailing of shells overhead, and the crashing of cannon-ball in the dome of the Mahdi's tomb, told the imprisoned women, who were creeping together in corners and clinging to each other in terror, that the English had come at last, and that the Caliph had fallen and fled.

When Adila was set at liberty by the English Sirdar she learned that, in grief at the loss of their daughter, her parents had died, and so, ashamed to return to Assouan, after being a slave girl in Omdurman, she took service with a Greek widow who kept a bakery in Khartoum.

It was there the Sheikhs of the law-courts found her, and they proceeded to coax and flatter her, telling her she had been a good girl who had seen much sorrow, and therefore ought to know some happiness now, to which end they had found a husband to marry her, and he was a fine handsome man, young and learned and rich.

At this Adila, remembering the Caliph, and thinking that such a person as they pictured could only want her as the slave of his bed, turned sharply upon them and said, "When did I ask you to find me a man?" and the Sheikhs had to go back discomfited.

Meanwhile Ishmael, raving against the Christians who were corrupting Mohammedans while he was lying helpless in his prison, fell into a fever, and the Greek mistress of Adila, hearing who had been meant for her handmaiden, and fearing the girl might think too much of herself, began to taunt and mock her.

"They told you he was rich, didn't they?" said the widow. "Well, he has no bread but what the Government gives him, and he is in chains and he is dying, and you would only have had to nurse him and bury him. That's all the husband you would have got, my girl, so perhaps you are better off where you are."

But the widow's taunting went wide, for as soon as Adila had heard her out she went across to the Mohammedan court-house and said —

"Why didn't you tell me it was Ishmael Ameer you meant?"

The Sheikhs answered with a show of shame that they had intended to do so eventually, and if they had not done so at first it was only out of fear of frightening her.

"He's sick and in chains, isn't he?" said Adila.

They admitted that it was true.

"He may never come out of prison alive – isn't that so?"

They could not deny it.

"Then I want to marry him," said Adila.

"What a strange girl you are!" said the Sheikhs, but without more ado the contract was made while Ishmael was so sick that he knew little about it, the marriage document was drawn up in his name, Adila signed it, half her dowry was paid to her, and she promptly gave the money to the poor.

Next day Ishmael was tossing on his angerib in the mud hut which served for his cell when he saw his Soudanese guard come in, followed by four women, and the first of them was Adila, carrying a basket full of cakes such as are made in that country for a marriage festival. One moment she stood over him as he lay on his bed with what seemed to be the dews of death on his forehead, and then putting her basket on the ground she slipped to her knees by his side and said —

"I am Adila. I belong to you now, and have come to take care of you."

"Why do you come to me?" he answered. "Go away. I don't want you."

"But we are married, and I am your wife, and I am here to nurse you until you are well," she said.

"I shall never be well," he replied. "I am dying and will soon be dead. Why should you waste your life on me, my girl? Go away, and God bless you. Praise to His name!"

With that she kissed his hand and her tears fell over it, but after a moment she wiped her eyes, rose to her feet, and turning briskly to the other women she said —

"Take your cakes and be off with you – I'm going to stay."

CHAPTER XIV

Three weeks longer Ishmael lay in the grip of his fever, and day and night Adila tended him, moistening his parched lips and cooling his hot forehead, while he raged against his enemies in his strong delirium, crying, "Down with the Christians! Drive them away! Kill them!" Then the thunging and roaring in his poor brain ceased, and his body was like a boat that had slid in an instant out of a stormy sea into a quiet harbour. Opening his eyes, with his face to the red wall, in the cool light of a breathless morning, he heard behind him the soft and mellow voice of a woman who seemed to be whispering to herself or to Heaven, and she was saying —

"Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive them that trespass against us; and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil; for Thine is the kingdom, the power, and the glory. Amen."

"What is that?" he asked, closing his eyes again, and at the next moment the mellow voice came from somewhere above his face —

"So you are better? Oh, how good that is! I am Adila. Don't you remember me?"

"What was that you were saying, my girl?"

"That? Oh, that was the prayer of the Lord Isa (Jesus)."

"The Lord Isa?"

"Don't you know? Long ago my father told me about Him, and I've not forgotten it even yet. He was only a poor man, a poor Jewish man, a carpenter, but He was so good that He loved all the world, especially sinful women when they were sorry, and little helpless children. He never did harm to His enemies either, but people were cruel and they crucified Him. And now He is in heaven, sitting at God's right hand, with Mary His mother beside Him."

There was silence for a moment, and then —

"Say His prayer again, Adila."

So Adila, with more constraint than before, but still softly and sweetly, began afresh —

"Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be Thy name; Thy kingdom come; Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven; give us this day our daily bread; and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive them that trespass against us; and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil; for Thine is the kingdom, the power, and the glory. Amen."

Thus the little Coptic woman, in her soft and mellow voice, said her Lord's prayer in that mud hut on the edge of the desert, with only the sick man to hear her, and he was a prisoner and in chains; but long before she had finished, Ishmael's face was hidden in his bed-clothes and he was crying like a child.

There were three weeks more of a painless and dreamy convalescence, in which Adila repeated other stories her father had told her, and Ishmael saw Christianity for the first time as it used to be, and wondered to find it a faith so sweet and so true, and above all, save for the character of Jesus, so like his own.

Then a new set of emotions took possession of him, and with returning strength he began to see Adila with fresh eyes. He loved to look at her soft, round form, and he found the air of his gloomy prison full of perfume and light as she walked with her beautiful erect bearing and smiling blue eyes about his bed. Hitherto she had slept on a mattress which she had laid out on the ground by the side of his angerib, but now he wished to change places, and when nothing would avail with her to do so, he would stretch out his arm at night until their hands met and clasped and thus linked together they would fall asleep.

But often he would awake in the darkness, not being able to sleep for thinking of her, and, finding one night that she was awake too, he said in a tremulous voice —

"Will you not come on to the angerib, Adila?"

"Should I?" she whispered, and she did.

Next day the black Soudanese guard that had been set to watch him reported to the Mohammedan Sheikhs that the devotee had been swallowed up in the man, whereupon the Sheikhs, with a chuckle, reported the same to the Government, and then Ishmael, with certain formalities, was set free.

At the expense of his uncle a house was found for him outside the town, for in contempt of his weakness in being tricked, as his people believed, by a Coptic slave girl, his following had gone, and he and Adila were to be left alone. Little they recked of that, though, for in the first sweet joys of husband and wife they were very happy, talking in delicious whispers, and with the frank candour of the East, of the child that was to come. He was sure it would be a girl, so they agreed to call it Ayesha (Mary), she for the sake of the sinful soul who had washed her Master's feet with her tears and wiped them with the hair of her head, and he in memory of the poor Jewish woman, the mother of Isa, whose heart had been torn with grief for the sorrows of her son.

But when at length came their day of days, at the height of their happiness a bolt fell out of a cloudless sky, for though God gave them a child, and it was a girl, He took the mother in place of it.

She made a bravo end, the sweet Coptic woman, only thinking of Ishmael and holding his hand to cheer him. It was noon, the sun was hot outside, and in the cool shade of the courtyard three Moslems chanted the "Islamee la Illaha," for so much they could do even for the infidel, while Ishmael sat within on one side of his wife's angerib, with his uncle, seventy years of age now, on the other. She was too weak to speak to her husband, but she held up her mouth to him like a child to be kissed.

A moment later the old man closed her eyes and said —

"Be comforted, my son – death is a black camel that kneels at the gate of all."

There were no women to wail outside the house that night, and next day, when Adila had to be buried, it was neither in the Mohammedan cemetery with those who had "received direction," nor in the Christian one with English soldiers who had fallen in fight, that the slave-wife of a prisoner could be laid, but out in the open desert, where there was nothing save the sand and the sky.

They laid her with her face to Jerusalem, wrapped in a cocoa-nut mat, and put a few thorns over her to keep off the eagles, and when this was done they would have left her, saying she would sleep cool in her soft bed, for a warm wind was blowing and the sun was beginning to set; but Ishmael would not go.

In his sorrow and misery, his doubt and darkness, he was asking himself whether, if his poor Coptic wife was doomed to hell as an unbeliever, he could ever be happy in heaven. The moon had risen when at length they drew him away, and even then in the stillness of the lonely desert he looked back again and again at the dark patch on the white waste of the wilderness in which he was leaving her behind him.

Next morning he took the child from the midwife's arms and, carrying it across to his uncle, he asked him to take care of it and bring it up, for he was leaving Khartoum and did not know how long he might be away. Where was he going to? He could not say. Had he any money? None, but God would provide for him.

"Better stay in the Soudan and marry another woman, a believer," said his uncle; and then Ishmael answered in a quivering voice —

"No, no, by Allah! One wife I had, and if she was a Christian and was once a slave, I loved her, and never – never – shall another woman take her place."

He was ten years away, and only at long intervals did anybody hear of him, and it was sometimes from Mecca, sometimes from Jerusalem, sometimes from Rome and finally from the depths of the Libyan desert. Then he reappeared at Alexandria, and entering a little mosque he exercised his right as Alim and went up into the pulpit to preach.

His teaching was like fire, and men were like fuel before it. Day by day the crowds increased that came to hear him, until Alexandria seemed to be aflame, and he had to remove to the large mosque of Abou Abbas in the square of the same name.

Such was the man whom Gordon Lord was sent to arrest.

CHAPTER XV

"HEADQUARTERS, CARACOL ATTARIN,

"ALEXANDRIA.

"MY DEAREST HELENA, – I have seen my man and it is all a mistake! I can have no hesitation in saying so – a mistake! Wallahi! Ishmael Ameer is not the cause of the riots which are taking place here – never has been, never can be. And if his preaching should ever lead by any indirect means to sporadic outbursts of fanaticism the fault will be ours – ours, and nobody else's.

"Colonel Jenkinson and the Commandant of Police met me on my arrival. It seems my coming had somehow got wind, but the only effect of the rumour had been to increase the panic, for even the conservative elements among the Europeans had made a run on the gunsmiths' shops for firearms and – could you believe it? – on the chemists' for prussic acid to be used by their women in case of the worst.

"Next morning I saw my man for the first time. It was outside Abou Abbas on the toe of the East port, where the native population, with quiet Eastern greeting, of hands to the lips and forehead, were following him from his lodging to the mosque.

"My dear girl, he is not a bit like the man you imagined. Young – as young as I am, at all events – tall, very tall (his head showing above others in a crowd) with clean-cut face, brown complexion, skin soft and clear, hands like a woman's, and large, beaming black eyes as frank as a child's. His dress is purely Oriental, being white throughout save for the red slippers under the caftan and the tip of the tarboosh above the turban. No mealy-mouthed person, though, but a spontaneous, passionate man, careless alike of the frowns of men and the smiles of women, a real type of the Arab out of the desert, uncorrupted by the cities, a man of peace perhaps, but full of deadly fire and dauntless energy.