полная версия

полная версияThe White Prophet, Volume I (of 2)

That was what his soul was saying to itself, but at the same time his body was carrying him away – through the open gate and across the deserted square, swiftly, stealthily, like a criminal leaving the scene of his crime.

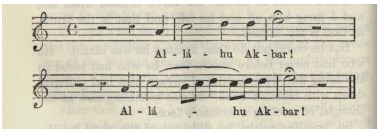

The day was now gone, the twilight was deep, and as he passed under the outer port of the Citadel in the dead silence of the unquickened air, a voice like that of an accusing angel, telling of judgment to come, fell upon his ear. It was the voice of the last of the muezzin on the minaret of the Mohammed Mosque calling to evening prayer – "God is Most Great! God is Most Great!"

Music fragment

END OF FIRST BOOK

SECOND BOOK

THE SHADOW OF THE SWORD

CHAPTER I

When Helena had left the General and Ishmael Ameer together, the signs she knew so well of illness in her father's face suggested that she should run at once for the Medical Officer. One moment she stood in the room adjoining the General's office, listening to the muffled rumble that came from the other side of the wall, the short snap of her father's impatient voice and the deep boom of the Egyptian's, and then she hurried into the outer passages to pin on her hat. There she met the General's Aide-de-camp, who, seeing her excitement, asked if there was anything he could do for her, but she answered "No," and then —

"Yes, I think you might go over to the Colonel" (meaning the Colonel commanding the Citadel) "and tell him this man is here with a crowd of his followers."

"He must know it already, but I'll go with pleasure," said the young Lieutenant. At the next moment there were three hasty beats on the General's bell, followed by a summons from the General's soldier servant, but the Aide-de-camp had disappeared.

Helena went out by the back of the house, and seeing her cook and the black boy as she passed the kitchen quarters an impulse came to her to send somebody else on her errand, lest anything should happen in her absence; but telling herself that nobody but herself and the Doctor must know the secret of her father's condition, she hurried along.

Her way was through the unoccupied courts of the old palace, down a flight of long steps, through an old gateway whereof the iron-clamped door always stood open, across a disused drawbridge, and so on to the open parade-ground. The Army Surgeon's quarters were on the farther side of it, and never before had it seemed so broad.

When she reached her destination the Surgeon was out on his evening round of the hospital, so she wrote a hurried note asking him to come to the General's house immediately, sent his assistant in search of him, and then turned back.

Returning hurriedly by the "married quarters," she was detained for some moments by a soldier's wife, a young thing, almost a child, who stood at the door of her house with a red woollen shawl about her shoulders, a baby in long clothes in her arms, and a look of radiant happiness in her round face.

"Ye've not seen 'im yet, have ye, Miss?" said the little mother, holding out her baby to be admired. "Only six weeks old and 'e weighs ten pounds. Colonel says as 'ow 'e's a credit to the reg'ment, and I'm agoin' to shorten 'im soon. To-morrow I'm 'avin' 'im photoed to send to mother. She lives in Clerkenwell, Miss, and she ain't likely to show 'is photo to nobody in our court. Oh no!"

Helena did her best to play up to the pride of the little Cockney mother, and was turning to go when the girl said —

"But my Harry tells me as how you're to be married yourself soon, so I wish ye joy, and many of 'em."

"Good-bye, Mrs. Dimmock," said Helena, but the young thing was not yet done. With a look of wondrous wisdom she said —

"They're a deal of trouble, Miss, but there ain't no love in the house without 'em. As mother says, they keeps the pot a-boilin'," and she was ducking down her head to kiss the child as Helena hurried away.

In the bright light of the young mother's life and the breadth of shadow that lay upon her own, Helena thought of Gordon and her anger rose against him again, but at the next moment she saw him in her mind's eye as she had seen him last, going out of the garden, a broken, bankrupt man, and then her eyes filled and it was as much as she could do to see her way.

In the quickening flow of her emotion this riot in her heart between anger with Gordon and with herself only led to deeper hatred of the Egyptian, and even the memory of his dignity and largeness in the single moment in which she had looked upon him made her wrath the more intense.

A vague fear, an indefinite forewarning, hardly able yet to assume a shape, was beginning to take possession of her. She recalled the scene she had left behind her in the General's office, the two men face to face, as if in the act of personal quarrel, and told herself that if anything happened to her father as the result of the excitement caused by the meeting, the Egyptian would be the cause of it.

In her impatience to be back she began to run. How broad the parade ground was! The air, too, was so close and lifeless. The sun had nearly set, the arms of night were closing round the day, but still the sky was a hot, dark red like the inside of a transparent shell that had a smouldering fire outside of it.

At one moment she heard hoarse and jarring voices that seemed to come from the square of the mosque in front of the house. Perhaps the Egyptian and his people were going off with their usual monotonous chanting of "Allah! Allah!" She was glad to reach the cool shade and silence of the empty courts of the old palace, but coming to the gateway she found it closed.

A footstep was dying away within, so she knocked and called, and after a moment an old soldier, a kind of caretaker of the Citadel, opened the gate to her.

"Beg pardon, Miss! Lieutenant Robson told me to shut up everything immediately," he said, but Helena did not wait for further explanation.

There was nobody in sight when she passed the kitchen quarters, and when she entered the house a chill silence seemed to strike to the very centre of her life.

Then followed one of those mystic impulses of the human heart which nobody can understand. In her creeping fear of what might have happened during her absence she was at first afraid to go into her father's room. If she had done so, there and then, and without an instant's hesitation, she must have found Gordon kneeling over her father's body. But in dread of learning the truth she tried to keep back the moment of certainty, and in a blind agony of doubt she stood and tried to think.

The voices of the men were no longer to be heard through the wall, and the deep rumble of the crowd outside had died away, therefore the Egyptian must have gone. Had her father gone too? She remembered that he was in uniform, and took a step back into the hall to see if his cap hung on the hat-rail. The cap was there. Had he gone into his bedroom? She crossed to the door. The door was open and the room was empty.

Hardly able to analyse her unlinked ideas, but with a gathering dread of the unknown, she found herself stepping on tiptoe towards the General's office. Then she thought she heard a faint cry within, a feeble, interrupted moan, and in an unsteady voice she called.

There was no answer. She called again, and still there was no reply. Then girding up her heart to conquer a vague fear, which hardly knew itself yet for what it was, she opened the door.

The room was almost dark. She took one step into the gloom, breathing rapidly, then stopped and said —

"Father! Are you here, father?"

There was no sound, so she took another step into the room, thinking to switch on the light over the desk and at the same time to reach the sofa. As she did so she stumbled against something, and her breath was struck out of her in an instant.

She stooped in the darkness to feel what it was that lay at her feet, and at the next moment she needed no light to tell her.

"Father! Father!" she cried, and in the dead silence that followed, the voice of the muezzin came from without.

She was lying prostrate over her father's body when the door was burst open as by a gust of wind and the Army Surgeon came into the room. Without a word he knelt and laid his hand over the heart of the fallen man, while Helena, who rose at the same instant, watched him in the awful thraldom of fear.

Then young Lieutenant Robson came in hurriedly, switching on the light and saying something, but the Surgeon silenced him with the lifting of his left hand. There was one of those blank moments in which time itself seems to stand still, while the Surgeon was on his knees and Helena stood aside with whitening lips and with eyes that had a wild stare in them. Then, lifting his face, which was stamped with the heaviness of horror and told before he spoke what he was going to say, the Surgeon rose, and turning to Helena, said in a nervous voice —

"I regret – I deeply regret to tell you…"

"Gone?" asked Helena, and the Surgeon bowed his head.

She did not cry or utter a sound. Only the trembling of her white lips showed what she felt, but all the cheer of life had died out of her face, and in a moment it had become hard and stony.

There was an instant of silence, and then the Surgeon and the young Lieutenant, casting sidelong looks at Helena, began to whisper together. At sight of her tearless eyes a certain fear had fallen on them which the presence of death could not create.

"Take her away," whispered the Surgeon, and then the Lieutenant, whose throat was hard and whose eyes were dim, approached her and said with the sadness of sympathy —

"May I help you to your room, please?"

Helena shook her head and stood immovable a moment longer, and then, with a firm step, she walked away.

CHAPTER II

All the moral cowardice that had paralysed Gordon Lord was gone the moment he left the Citadel, and as soon as he reached the streets of the city the power of life came back to him. There, in tumultuous swarms, the native people were swinging along in one direction, uttering the monotonous cries of the Moslems when they are deeply moved. Into this maelstrom of emotion Gordon was swept before he knew it, and hardly conscious of where he was going he followed where he was led.

He felt, without knowing why, the lust of violence which comes to the soldier in battle who wants to run away until the moment when the first shot has been fired, and then – all fear and moral conscience gone in an instant – forges his path with shouts and oaths to where danger is greatest and death most sure.

In the thickening darkness he saw a great glow coming from a spot in front of him, as of many lanterns and torches burning together. Towards this spot he pushed his way, calling to the people in their own tongue to let him pass, or sweeping them aside and ploughing through. In his delirious excitement his strength seemed to be supernatural, and men were flung away as if they had been children.

At length he reached a place where a narrow lane, opening on to a square, was blocked by a line of soldiers, who were coming and going with the glare of the torch-light on their faces. Here the monotonous noises of the crowd behind him were pierced by sharp cries, mingled with screams. Perspiration was pouring down Gordon's neck by this time, and he stopped to see where he was. He was at the big gate of El Azhar.

On leaving the Citadel, Colonel Macdonald had taken two squadrons with him, telling the Lieutenant-Colonel commanding the regiment to follow with the rest.

"Half of these will be enough for this job, and we'll clear the rascals out like rats," he said.

The Governor of the city, a small man in European dress, acting on the order of the Minister of the Interior as Regent in the absence of the Khedive, had met him at the University. They found the gate shut and barred against them, and when the Governor called for it to be opened there was no reply. Then the Colonel said —

"Omar Bey, have I your permission to force an entrance?"

Whereupon the Governor, in whom the wine of life was chiefly vinegar, answered promptly —

"Colonel, I request you to do so."

A few minutes afterwards a stout wooden beam was brought up from somewhere, and six or eight of the soldiers laid hold of it and began to use it on the closed gate as a battering ram. The gate was a strong one clamped with iron, but it was being crunched by the blows that fell on it when some of the students within clambered on to the top of the walls and hurled down stones on the heads of the soldiers.

One of them was a young boy of not more than fourteen years, and while others protected themselves by hiding behind the coping stones, he exposed his whole body to the troops by standing on the very crest of the parapet. The windows of the houses around were full of faces, and from one that was nearly opposite to the gate came the shrill cry of a woman, calling on the boy to go back. But in the clamour of noises he heard nothing, or in the fire of his spirit he did not heed, for he continued to hurl down everything that came to his hand, until Colonel Macdonald commanded the troop to dismount with rifles and said —

"Stop that young devil up there!"

At the next moment there was the crack of a dozen rifles, and the boy on the parapet swayed aside, lurched forward, and fell into the street. The Colonel was giving orders that he should be taken up and carried away when the woman's cry was heard again, this time in a frenzied shriek, and at the next instant the soldiers had to make way for the mightiest thing on earth, an outraged mother in the presence of her dead.

The woman, who had torn the black veil from her face, lifted the boy's head to her breast and cried, "My God! My good God! My boy! Ali! Ali!" But just then the gate gave way with a crash, and the Colonel ordered one of the squadrons to ride into the courtyard of the mosque, where five thousand of the students and their professors could be seen squirming in dense masses like ants on an upturned ant-hill.

The soldiers were forcing their horses through the crowds and beating with the flat of their swords when two or three shots were fired from within, and it became certain that some of the students were using firearms. At that the bulldog in the British Colonel got the better of the man, and he wanted to shout a command to his men to use the edge of their weapons and clear the place at any cost, but the shrill cry of the mother over her dead boy drowned his thick voice.

"He is dead! They have killed him! My only child! His father died last week. God took him, and now I have nobody. Ali, come back to me! Ali! Ali!"

"Take that yelping b – away!" shouted the Colonel, ripping out an oath of impatience, and that was the moment when Gordon Lord came up.

What he did then he could never afterwards remember, but what others saw was that with the spring of a tiger he leapt up to Macdonald, laid hold of him by the collar of his khaki jacket, dragged him from the saddle, flung him headlong on the ground, and stamped on him as if he had been a poisonous snake.

In another moment there would have been no more Macdonald, but just then, while the soldiers, recognising their First Staff Officer, stood dismayed, not knowing what it was their duty to do, there came over the sibilant hiss of the crowd the loud clangour of the hoofs of galloping horses, and the native people laid hold of Gordon and carried him away.

His great strength was now gone, and he felt himself being dragged out of the hard glare of the light into the shadow of a side street, where he was thrust into a carriage and held down in it by somebody who was saying —

"Lie still, my brother! Lie still! Lie still!"

For one instant longer he heard deafening shouts through the carriage glass, over the rumble of the moving wheels, and then a blank darkness fell on him for a time and he knew no more.

When he recovered consciousness his mind had swung back, with no memory of anything between, to the moment when he was leaving the General's house, and he was saying to himself again, "I must go back. She may curse me, but I cannot leave her alone. I cannot – I will not."

Then he was aware of a voice – it was the quavering voice of an old man, and seemed to come out of a toothless mouth – saying —

"Be careful, Michael! His poor hand is injured. We must send for the surgeon."

He opened his eyes and saw that he was being carried through a quiet courtyard where he could hear the footsteps of the men who bore him and see by the light of a smoking lantern the façade of a church. Then he heard the same quavering voice say —

"Take him up to the salamlik, my brother," and then there was a jerk and a jolt and he lost consciousness again.

He was lying on a bed in a dimly lighted room when memory returned and the events of the day unrolled themselves before him. He made an effort to raise himself on his elbows, but in his weakness he fell back, and after a while he dropped into a delirious sleep. In this sleep he saw first his mother and then Helena, and then Helena and again his mother – everything and everybody else being quite blotted out.

CHAPTER III

Soon after sunset Lady Nuneham had taken her last dose of medicine, and had got into bed, when the Consul-General came into her room. He had the worn and jaded look by which she knew that the day had gone heavily with him, and she waited for him to tell her how and why. With a face full of the majesty of suffering he told her what had happened, describing the scene in the General's office, and all the circumstances whereby matters had been brought to such a tragic pass.

"It was pitiful," he said. "The General went too far – much too far – and the sight of Gordon's white face and trembling lips was more than I could bear."

His voice thickened as he spoke, and it seemed to the mother at that moment as if the pride of the father in his son, which he had hidden so many years in the sealed chamber of his iron soul, had only come up at length that she might see it die.

"It's all over with him now, I suppose, and we must make the best of it. He promised so well, though! Always did – ever since he was a boy. If one's children could only remain children! The pity of it! Good-night! Good-night, Janet!"

She had listened to him without speaking and without a tear coming into her eyes, and she answered his "Good-night" in a low but steady voice. Soon afterwards the gong sounded in the hall, and, as she lay in her bed, she knew that he would be dining alone – one of the great men of the world, and one of the loneliest.

Meantime Fatimah, tidying up the room for the night and sniffling audibly, was talking as much to herself as to her mistress. At one moment she was excusing the Consul-General, at the next she was excusing Gordon. Lady Nuneham let her talk on, and gave no sign until darkness fell and the moment came for the Egyptian woman also to get into bed. Then the old lady said —

"Open the door of this room, Fatimah," pointing to a room on her right.

Fatimah did so, without saying a word, and then she lay down, blowing her nose demonstratively as if trying to drown other noises.

From her place on the pillow the old lady could now see into the adjoining chamber, and through its two windows on to the Nile. A bright moon had risen, and she lay a long time looking into the silvery night.

Somewhere in the dead waste of early morning the Egyptian woman thought she heard somebody calling her, and, rising in alarm, she found that her mistress had left her bed and was speaking in a toneless voice in the next room.

"Fatimah! Are you awake? Isn't the boy very restless to-night? He throws his arms out in his sleep and uncovers little Hafiz too."

She was standing in her nightdress and lace nightcap, with the moon shining in her face, by the side of one of the two beds the room contained, tugging at its eiderdown coverlet. Her eyes had the look of eyes that did not see, but she stood up firmly, and seemed to have become younger and stronger – so swiftly had her spirit carried her back in sleep to the woman she used to be.

"Oh my heart, no," said Fatimah. "Gordon hasn't slept in this room for nearly twenty years – nor Hafiz neither."

At the sound of Fatimah's husky voice and the touch of her moist fingers the old lady awoke.

"Oh yes, of course," she said, and after a moment, in a sadder tone, "Yes, yes."

"Come, my heart, come," said Fatimah, and taking her cold and nerveless hand, she led her, a weak old woman once more, back to her bed, for the years had rolled up like a tidal wave and the spell of her sweet dream was broken.

On a little table by the side of her bed stood a portrait of Helena in a silver frame, and she took it up and looked at it for a moment, and then the light which Fatimah had switched on was put out again. After a little while there was a sigh in the darkness, and after a little while longer a soft, tremulous —

"Ah, well!"

CHAPTER IV

Helena was still in her room when the Consul-General, who had been telephoned for, held an inquiry into the circumstances of the General's death. She was sitting with her hands clasped in her lap and her eyes looking fixedly before her, hardly listening, hardly hearing, while the black boy darted in and out with broken and breathless messages which contained the substance of what was said.

The household servants could say nothing except that, following in the wake of the new prophet when he left the Citadel, they had left the house by the side gate of the garden without being aware of anything that had happened in the General's office. The Surgeon testified to the finding of the General's body, and the Aide-de-camp explained that the last time he saw his chief alive was when he was ordered to call Colonel Macdonald.

"Who was with him at that moment?" asked the Consul-General.

"The Egyptian, Ishmael Ameer."

"Was there anything noticeable in their appearance and demeanour?"

"The General looked hot and indignant."

"Did you think there had been angry words between them?"

"I certainly thought so, my lord."

Other witnesses there were, such as the soldier servant at the door, who made a lame excuse for leaving his post for a few minutes while the Egyptian was in the General's office, and the sentry at the gate of the Citadel, who said no one had come in after Colonel Macdonald and the cavalry had passed out. Then, some question of calling Helena herself was promptly quashed by the Consul-General, and the inquiry closed.

Hardly had the black boy delivered the last of his messages when there was a timid knock at Helena's door, and the Army Surgeon came into the room. He was a small man with an uneasy manner: married, and with a family of grown-up girls who were understood to be a cause of anxiety to him.

"I regret – I deeply regret to tell you, Miss Graves, that your father's death has been due to heart-failure, the result of undue excitement. You will do me the justice – I'm sure you will do me the justice to remember that I repeatedly warned the General of the dangers of over-exciting himself, but unfortunately his temperament was such – "

The Consul-General's deep voice in the adjoining room seemed to interrupt the Surgeon, and making a visible call on his resolution he came closer to Helena and said —

"I have not mentioned my previous knowledge of organic trouble. Lord Nuneham asked some searching questions, but the promise I made to your father – "

Again the Consul General's voice interrupted him, and with a flicker of fear on his face, he said —

"Now that things have turned out so unhappily it might perhaps be awkward for me if … In short, my dear Miss Graves, I think I may rely on you not to … Oh, thank you, thank you!" he said, as Helena, understanding his anxiety, bowed her head.

"I thought it would relieve you to receive my assurance that death was due to natural causes only – purely natural. It's true I thought for a moment that perhaps there had also been violence – "

"Violence?" said Helena.

"Don't let me alarm you. It was only a passing impression, and I should be sorry, very sorry – "