полная версия

полная версияThe Book-lover

THE student of English literature has indeed embarked upon a limitless ocean. A lifetime of study will serve only to make him acquainted with parts of that great expanse which lies open before him. He should pursue his explorations earnestly, and with the inquiring spirit of a true discoverer. His thirst for knowledge should be unquenchable; he should long always for that mind food which brings the right kind of mind growth. He should not rest satisfied with merely superficial attainments, but should strive for that thoroughness of knowledge without which there can be neither excellence nor enjoyment.

English literature is not to be learned from manuals. They are only helps, – charts, buoys, light-houses, if you will call them so; or they serve to you the purposes of guide-books. What do you think of the would-be tourist who stays at home and studies his Baedeker with the foolish thought that he is actually seeing the countries which the book describes? And yet I have known students, and not a few teachers, do a thing equally as foolish. With a Morley, or a Shaw, or even a Brooke in their hands, and a few names and dates at their tongues’ ends, they imagine themselves viewing the great ocean of literature, ploughing its surface and exploring its depths, when in reality they are only wasting their time “in dalliance on the shore.”

English literature does not consist in a mere array of names and dates and short biographical sketches of men who have written books. Biography is biography; literature “is a record of the best thoughts.” But the former is frequently studied in place of the latter. “For once that we take down our Milton, and read a book of that ‘voice,’ as Wordsworth says, ‘whose sound is like the sea,’ we take up fifty times a magazine with something about Milton, or about Milton’s grandmother, or a book stuffed with curious facts about the houses in which he lived, and the juvenile ailments of his first wife.”23 Instead of becoming acquainted at first hand with books in which are stored the energies of the past, we content ourselves with knowing only something about the men who wrote them. Instead of admiring with our own eyes the architectural beauties of St. Paul’s Cathedral, we read a biography of Sir Christopher Wren.

Again, it must be borne in mind that literature is one thing, and the history of literature is another. The study of the latter, however important, cannot be substituted for that of the former; yet it is not desirable to separate the two. To acquire any serviceable knowledge of a book, you will be greatly aided by knowing under what peculiar conditions it was conceived and produced, – the history of the country, the manners of the people, the status of morals and politics at the time it was written. Between history and literature there is a mutual relationship which should not be overlooked. “A book is the offspring of the aggregate intellect of humanity,” and it gives back to humanity, in the shape of new ideas and new combinations of old ideas, not only all that which it has derived from it, but more, – increased intellectual vitality, and springs of action hitherto unknown.

In the study of literature, one should begin with an author and with a subject not too difficult to understand. A beginner will be likely to find but little comfort in Chaucer or Spenser, or even in Emerson; but after he has worked up to them he may study them with unbounded delight. For a ready understanding and correct appreciation of the great masterpieces of English literature, a knowledge of Greek and Roman mythology and history is almost indispensable. The student will find the courses of historical reading given in a former chapter of this book of much value in supplementing his literary studies.

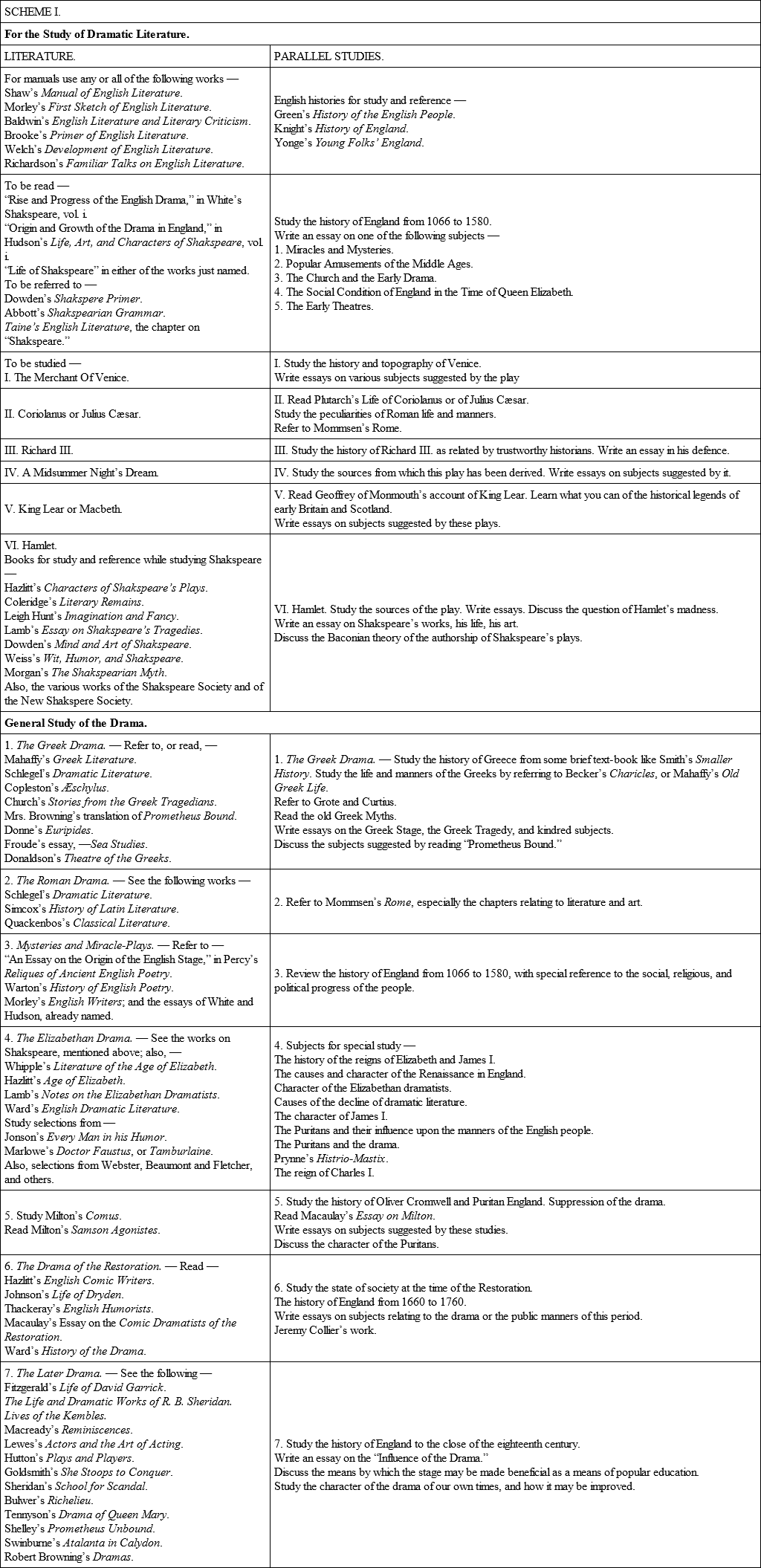

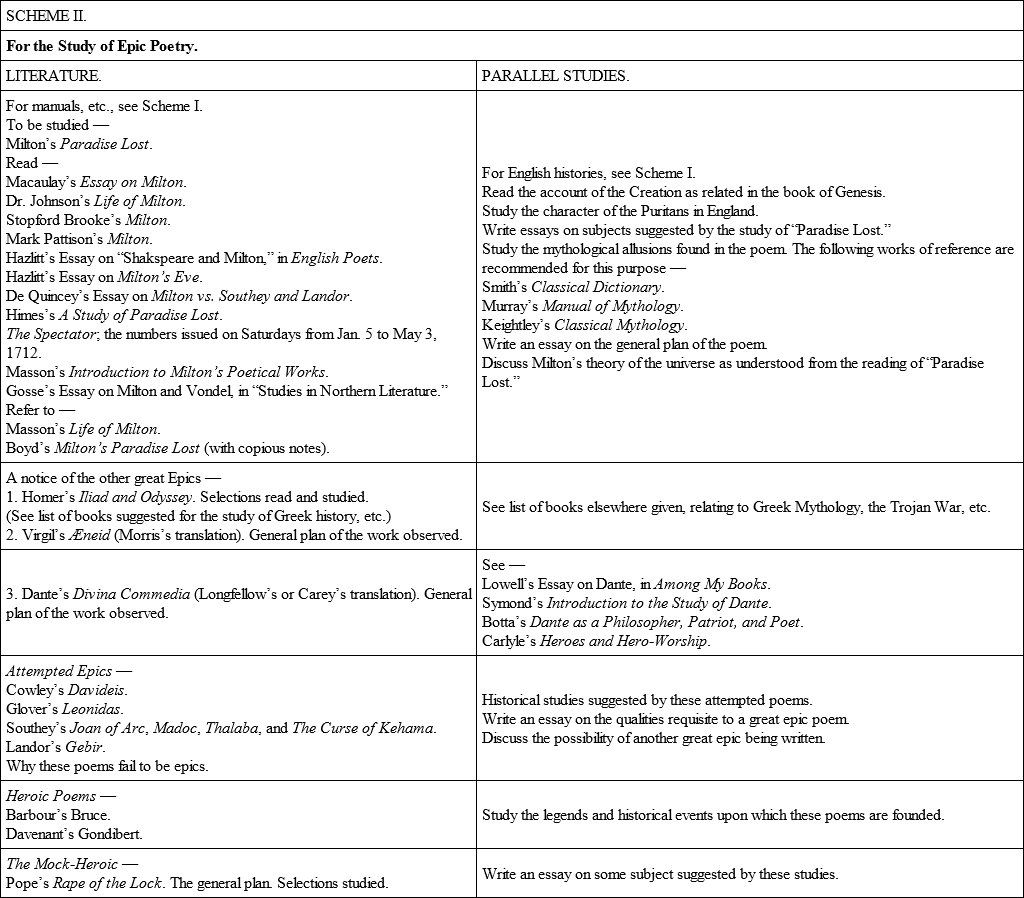

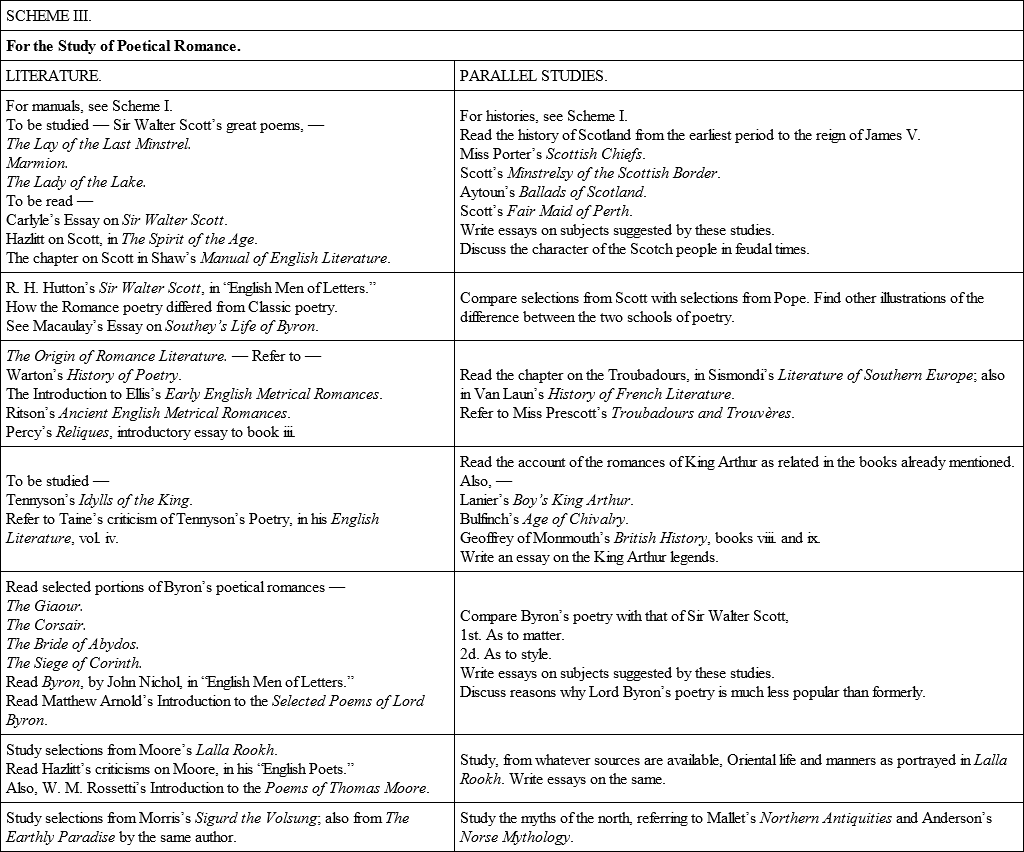

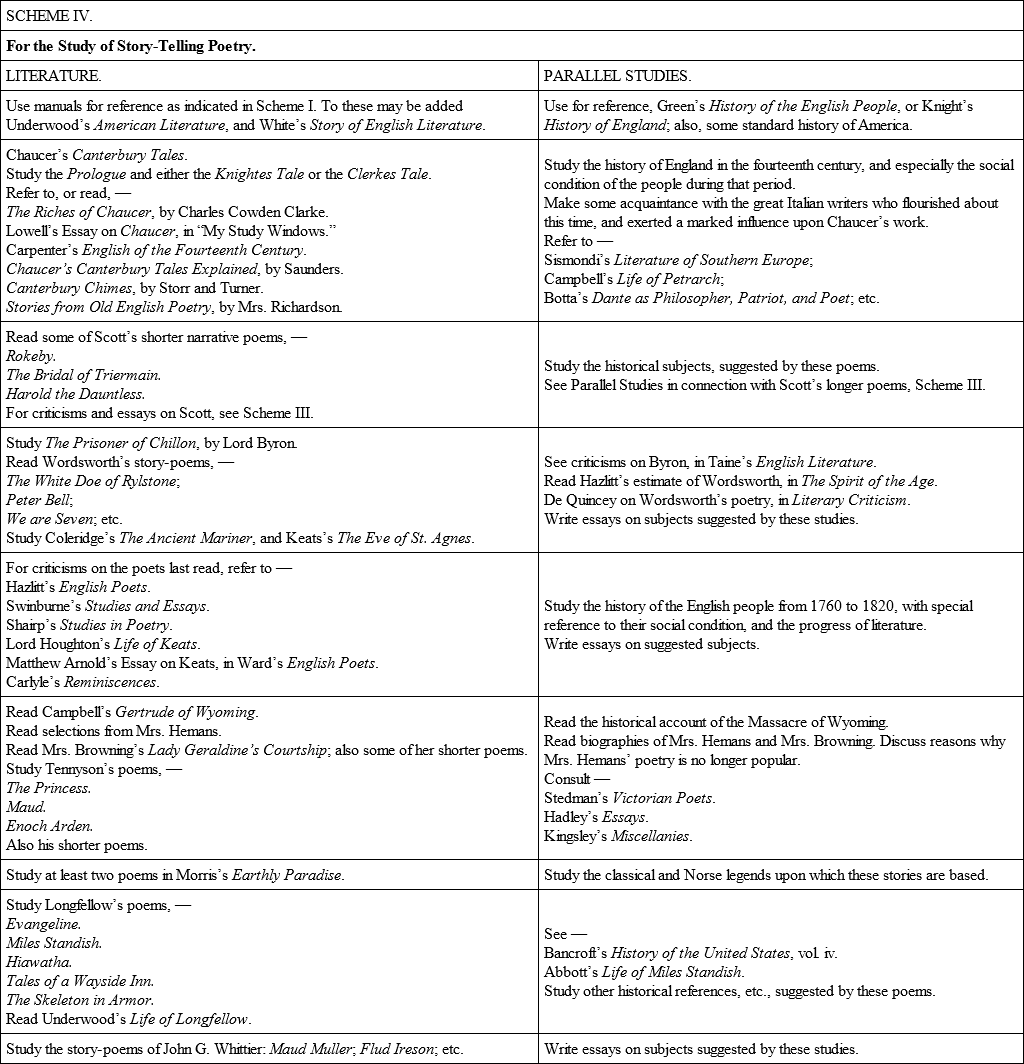

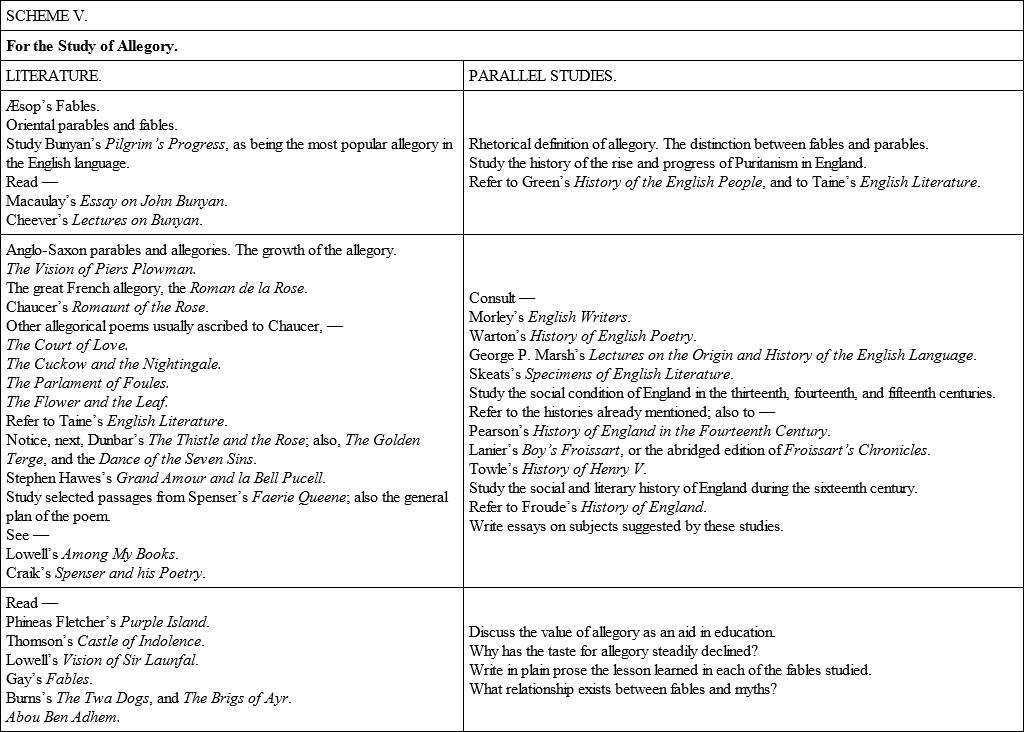

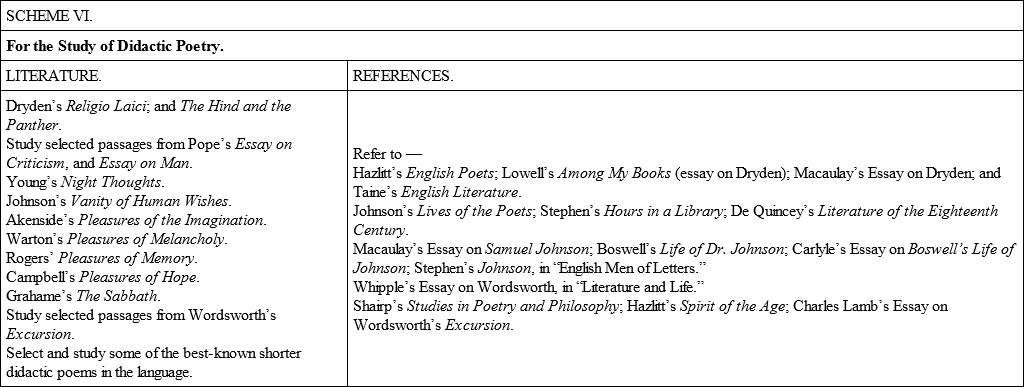

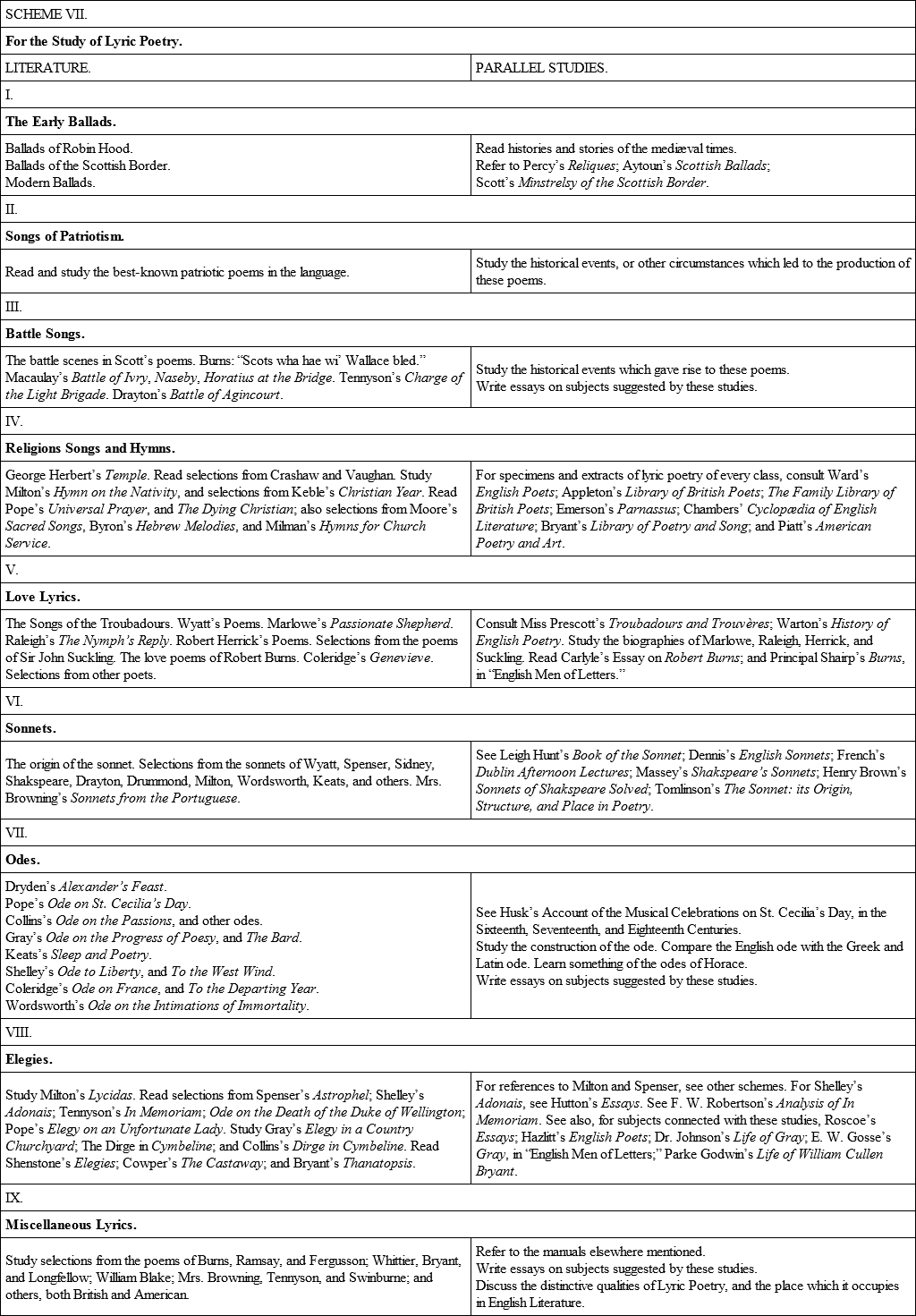

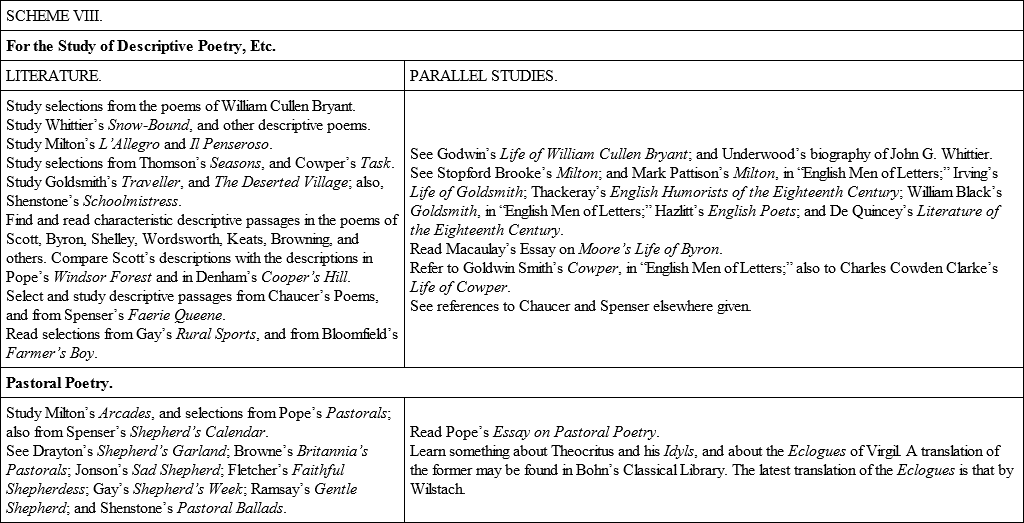

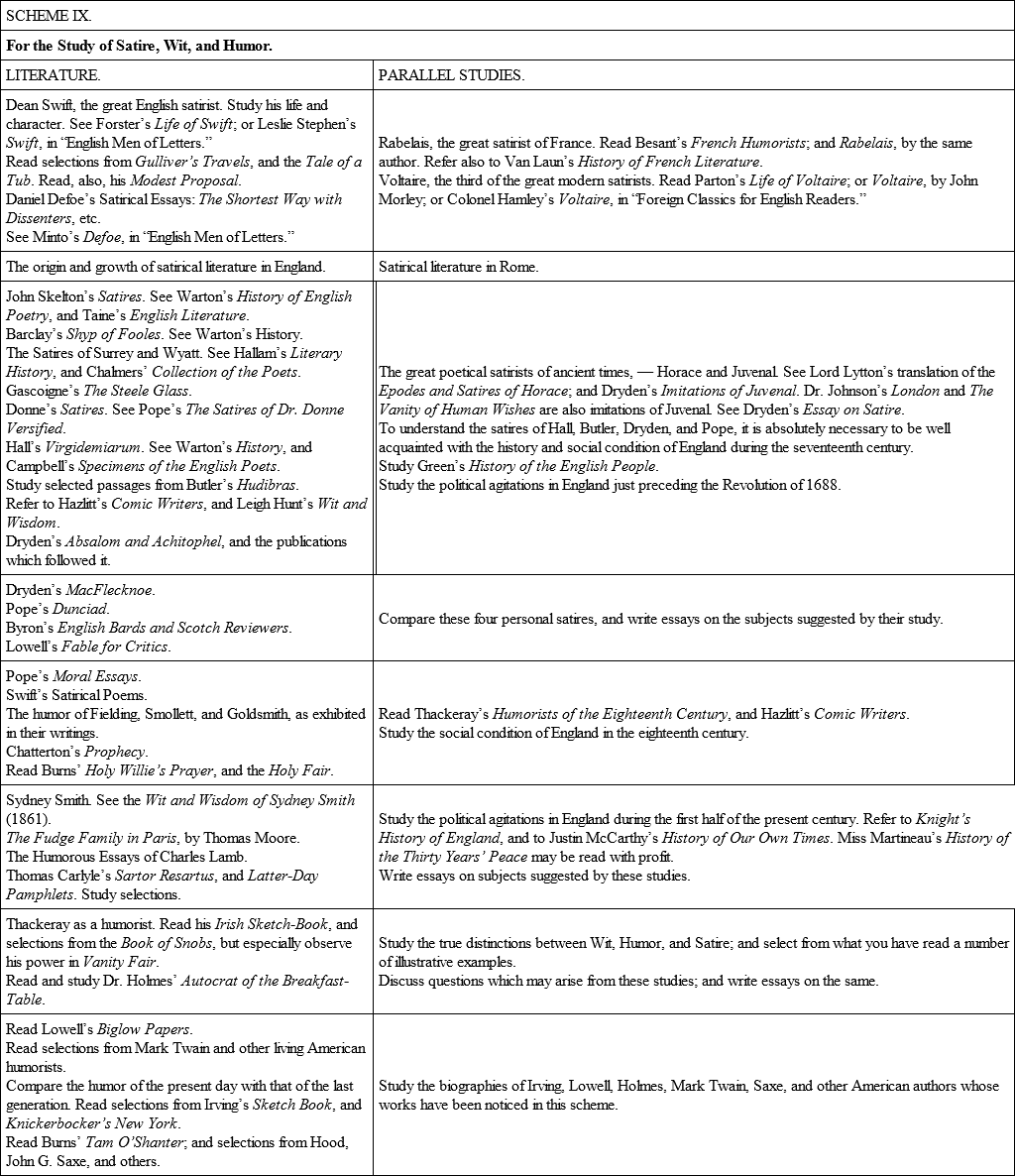

The great works of the world’s masterminds should be studied together, with reference to the similarity of their subject-matter. For example, the reading of Shakspeare will give occasion to the study of dramatic literature in all its forms; the reading of Milton’s “Paradise Lost” will introduce us to the great epics, and to heroic poetry in general; Sir Walter Scott’s “Lay of the Last Minstrel” will lead naturally to the romance literature of modern and mediæval times; Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales” fitly illustrate the story-telling phase of poetry; the study of lyric poetry may centre around the old ballads, the poems of Robert Burns, and the religious hymns of our language; Bunyan’s “Pilgrim’s Progress” introduces us to allegory, and Milton’s “Lycidas” to elegiac and pastoral poetry; and to know the best specimens of argumentative prose, we begin with the speeches of Daniel Webster and end with the orations of Demosthenes.

The following schemes for the study of different departments of English literature have been tested both with private students and with classes at school. Of course, many of the books mentioned are to be used chiefly as works of reference; some of them may be conveniently omitted in case it is desirable to abridge the course, and others may be exchanged for similar works upon the same subject.

ERE let us face the last question of all: In the shade and valley of Life, on what shall we repose? When we must withdraw from the scenes which our own energies and agonies have somewhat helped to make glorious; when the windows are darkened, and the sound of the grinding is low, – where shall we find the beds of asphodel? Can any couch be more delectable than that amidst the Elysian leaves of Books? The occupations of the morning and the noon determine the affections, which will continue to seek their old nourishment when the grand climacteric has been reached.

The Author of “Hesperides.”1

Robert Collyer: Addresses and Sermons.

2

The Doctor, Interchapter V., 1856.

3

Arthur Schopenhauer: Parerga und Paralipomena, 1851.

4

The Elements of Drawing, in Three Letters to Beginners, 1857.

5

The Spectator, No. 166.

6

Fortnightly Review (April, 1879), – “On the Choice of Books.”

7

Parerga und Paralipomena (1851).

8

The Critic (July 5, 1884), – “Leisure Reading.”

9

John Ruskin: Sesame and Lilies.

10

Guesses at Truth, by Two Brothers, 1848.

11

Society and Solitude, – “Books.”

12

George Gilfillan.

13

Friends in Council.

14

Views and Opinions, by Matthew Browne (W. H. Rands).

15

The Choice of Books.

16

Temple Bar (September, 1884), – “Barry Cornwall on the Reading of Books.”

17

Sesame and Lilies.

18

Meliora (October, 1867).

19

Sparks’s Life of Franklin, part i.

20

My Schools and Schoolmasters.

21

Memoir of Robert Chambers: with Autobiographic Reminiscences of William Chambers.

22

Chinese Classics, by J. Legge. 3 vols.

23

Frederic Harrison: Fortnightly Review (April, 1879), “On the Choice of Books.”