полная версия

полная версияA History of American Literature

I don’t know whether mine is a profession, or a trade, or what not… I am a schoolmaster, a private Tutor, a Surveyor, a Gardener, a Farmer, a Painter (I mean a House Painter), a Carpenter, a Mason, a Day-laborer, a Pencil-maker, a Glass-paper-maker, a Writer, and sometimes a Poetaster.

So as he was able to turn an honest penny whenever he needed one, and as his needs were few, he worked at intervals and betweenwhiles shocked many of his industrious townsfolk by spending long days talking with his neighbors, studying the ways of plants and animals in the near-by woods and waters, and occasionally leaving the village for trips to the wilds of Canada, to the Maine woods, to Cape Cod, to Connecticut, and, once or twice on business, to New York City. After college he became a devoted disciple and friend of Emerson. From the outset Emerson delighted in his “free and erect mind, which was capable of making an else solitary afternoon sunny with his simplicity and clear perception.” They differed as good friends should, Emerson acquiescing in laws and practices which he could not approve, and Thoreau defying them. The stock illustration is on the issue of tax-paying. Emerson, as a property-holder, paid about two hundred dollars and refused to protest at what was probably an undue assessment. Thoreau, outraged at the national policy in connection with the Mexican War, refused on principle to pay his few dollars for poll tax and had to be shut up by his good friend, Sam Staples, collector, deputy sheriff, and jailer, who tried in vain to lend him the money. Emerson visited him at the jail, where ensued the historic exchange of questions: “Henry, why are you here?” “Waldo, why are you not here?”

The records of the rambles of the two men are many. In his memorial essay on Thoreau, Emerson wrote:

It was a pleasure and a privilege to walk with him. He knew the country like a fox or a bird, and passed through it as freely by paths of his own. He knew every track in the snow or on the ground, and what creature had taken this path before him… On the day I speak of he looked for the Menyanthes, detected it across the wide pool, and on examination of its florets, decided it had been in flower five days.

Emerson’s records after walks with Thoreau are full of wood lore. He may have recognized the plants himself, but he seldom recorded them except when he had been with his more expert friend.

In 1839 Thoreau, in company with his brother, spent “A Week on the Concord and Merrimac Rivers,” from which he drew the material published ten years later in a volume with that title. It is a meandering record of the things he saw during the seven days and the thoughts suggested by them. In his lifetime the book was so complete a commercial failure that after some years he took back seven hundred of the thousand copies printed. In the meanwhile, from 1845 to 1847, he indulged in his best-known experience – his “hermitage” at Walden Pond, a little way out from Concord. This gave him the subject matter for his most famous book, “Walden,” published in 1854 and much more successful in point of sales. These two volumes, together with a few prose essays and a modest number of poems, were all that was given to the public during his lifetime. Since his death a large amount of the manuscript he left has been published, as shown in the list at the end of this chapter.

“Walden” is externally an account of the two years and two months of his residence at the lakeside, but it is really, like his sojourn there, a commentary and criticism on life. In the chapter on “Where I lived and What I lived for” he wrote:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived… I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then, to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.

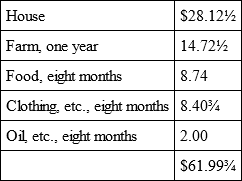

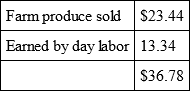

The actual report of his days by the lakeside can be separated from his decision as to what they were worth. He went out near the end of March, 1845, to a piece of land owned by Emerson on the shore of the pond. He cut his own timber, bought a laborer’s shanty for the boards and nails, during the summer put up a brick chimney, and counting sundry minor expenses secured a tight and dry – and very homely – four walls and ceiling for a total cost of $28.12–1/2. Fuel he was able to cut. Food he largely raised. His clothing bill was slight. So that his account for the first year runs as follows:

To offset these expenses he recorded:

leaving $25.21¾, which was about the cash in hand with which he started. The expense of the second year did not, of course, include the heaviest of the first-year items – the cost of the house.

I learned from my two years’ experience that it would cost incredibly little trouble to obtain one’s necessary food, even in this latitude… In short, I am convinced, both by faith and experience, that to maintain oneself on this earth is not a hardship but a pastime, if we will live simply and wisely; as the pursuits of the simpler nations are still the sports of the more artificial. It is not necessary that a man should earn his living by the sweat of his brow, unless he sweats easier than I do.

So much for the external account of the Walden years. The last words of the quotation give a cue to the criticism with which he accompanies the bare statement. This is contained chiefly in chapters I, “Economy” (the longest, amounting to one fourth of the book); II, “Where I lived and What I lived for”; V, “Solitude”; VIII, “The Village”; and XVIII, “Conclusion.” He contended that life had been made complex and burdensome because of the mistaken notion that property was much to be desired. This idea had led men to buy land and build houses, go into trade, construct railways and ships, and to set up government and rival governments, in order to protect the things men owned and those they were buying and selling. Being who he was, he asserted boldly and sometimes savagely a large number of charges against organized society and the men who submitted to it. “The laboring man has not leisure for a true integrity.” “The civilized man’s pursuits are not worthier than the savage’s.” “The college student obtains an ignoble and unprofitable leisure, defrauding himself.” “Thank God, I can sit and I can stand without the aid of a furniture warehouse.” “Men say a stitch in time saves nine, so they take a thousand stitches to-day to save nine to-morrow.” “Society is commonly too cheap.” “Wherever a man goes, men will pursue and paw him with their dirty institutions, and, if they can, constrain him to belong to their desperate, odd-fellow society.” At this point he challenges comparison again with Crèvecœur (see p. 60). To the hearty immigrant of the eighteenth century the common right to own the soil and to enjoy the fruits of labor seemed almost millennial in view of the Old World conditions which denied these privileges to the masses. To the New England townsman the ownership of property was oppressive in view of the aboriginal right to traverse field and forest without any obligation to maintain an establishment or “improve” an acreage. In Crèvecœur’s France, where for centuries the people had lived on sufferance, tenure of the land seemed an inestimable privilege. Thoreau’s America seemed so illimitable that he apparently supposed land would always be “dirt cheap.” Yet though one prized property and the other despised it, they were alike in not foreseeing the economic changes that the nineteenth century was to produce.

The more positive side of Thoreau’s criticism lies in the passages in which he told how excellent was his way of living, how full of freedom and leisure and how blest with solitude. There is no question that he did live cheaply, easily, happily, and independently, nor is there any question that the love of money and what it represents has made life more of a burden than a joy for millions of people; but there is this immense difference between the independence of Thoreau and the independence of Emerson – that Emerson discharged his duties in the family and in the state and that Thoreau protested at his obligations to the group even while he was reaping the benefits of other men’s industry. At Walden he lived on land owned by Emerson, who bought it and paid the taxes on it. The bricks and glass and nails in his shanty and the tools he borrowed to build it with were the products of mines and factories and kilns brought to him on the railroads and handled by the shopkeepers whom he scorned. He was therefore in the ungraceful position of being a beneficiary of society while he was carrying on a kind of guerrilla warfare against it.

As a citizen and as a critic of society Thoreau lacked the sturdy Puritan conscience which is the bone and sinew of Emerson’s character, and he lacked the “high seriousness” of his greater townsman. In consequence, instead of being serenely self-reliant he was often petulant; and instead of being nobly dignified he was nervously on guard against deserved rebuke. Emerson frequently uttered and wrote striking sentences which surprise one into pleased attention, Thoreau came out with smart and clever sayings like an eager and half-naughty boy who is trying to shock his elders. Almost the only rejoinder that his protests called forth must have been disturbing to him, because Oliver Wendell Holmes was so unruffled as he wrote his “Contentment.” Holmes seems to have said:

Little I ask, my wants are few;and then in playful satire he told about the hut – of stone – on Beacon Street that fronts the sun, where he too could live content with a well-set table, the best of clothes, furniture, jewelry, paintings, and a fast horse when he chose to take an airing. This was the attitude of many good-humored men and women of the world who were inclined to smile indulgently at whatever came out of Concord.

However, a fair estimate of Thoreau and his case against the world should steer the wise course between taking him too seriously and literally and not taking him seriously at all, between Stevenson’s scathing attack in “Familiar Portraits” and Holmes’s supercilious “Contentment.” If one elects to act as a prosecuting attorney, one can say of him what Thoreau quotes a friend as saying of Carlyle, that he “is so ready to obey his humour that he makes the least vestige of truth the foundation of any superstructure, not keeping faith with his better genius nor truest readers.” But if one choose to value him as a friend might, one can exonerate him in the light of a warning and a confession of his own: “I trust that you realize what an exaggerator I am, – that I lay myself out to exaggerate whenever I have an opportunity, – pile Pelion upon Ossa, to reach heaven so.” This is the very point of his title-page inscription to “Walden”:It is easy to compare Emerson and Thoreau to the disadvantage of the younger man. But at one point they were quite alike, and that is in the fact that both were more social in their lives than in their writings. Thoreau was not an unmitigated anarchist, or hermit, or loafer. He was more capable and industrious than he admits; he was devoted to his family and a loyal friend. In his protest at the ways of the world he was, in a manner, “whistling to keep his courage up,” and often his whistling became rather shrill. The greater part of “Walden” and, indeed, of his writing as a whole is the work of a naturalist – the work included in such chapters as “Sounds,” “The Ponds,” “Brute Neighbors,” “Former Inhabitants,” and "Winter Visitors,” “Winter Animals,” and “The Pond in Winter.” In the two generations since Crèvecœur’s “Letters from an American Farmer” no one on this side the Atlantic had written about the out of doors with such fullness and intimate knowledge. In this respect, moreover, Thoreau, instead of being a student or imitator of Emerson, was his guide and instructor. Although modern science owes little to him and has corrected many of his findings, it recalls his help to Agassiz in collecting specimens; and modern literature has produced only one or two men, like John Burroughs and John Muir, who write of nature with the same sympathy and beauty. The title of his friend Channing’s book “Thoreau: the Poet-Naturalist” tells the whole story. He was fascinated by growing things. He could not learn enough about their ways. The life in Concord’s rivers, ponds, fields, and woods by day and night and during the changing seasons was an endless study and pleasure. In his journal he kept a detailed record of the pageant of the year, which after his death was assembled in the four volumes “Spring in Massachusetts,” “Summer,” “Autumn,” and “Winter.” When he went to other parts of the country he carried his knowledge of Concord as a sort of reference book. From Staten Island he wrote: “The woods are now full of a large honeysuckle in full bloom, which differs from ours… Things are very forward here compared with Concord.” In the Maine woods he recognized his old familiars but in more massively primitive surroundings than those at home. The sandy aridity of Cape Cod furnished him daily with fascinating contrasts, in natural surroundings and in their effect on the residents. On his trip to Mount Washington he found forty-two of the forty-six plants he expected, adding one to his list when, after falling and spraining his ankle, he limped a few steps and said, “Here is the arnica, anyhow,” reaching for an arnica mollis, which he had not found before. And when he chose to put into essay form some of the information he had gleaned, he was exact without being technical and never for long repressed his lively spirits.

The poet in him brought him back continually to the beauty in what he saw. He did not particularly incline to philosophize about creation like Emerson, the sheer facts of it meant so much more to him. Nor did he care to expound the beauties of nature; he simply held them up to view. Take, for example, this bit from “The Pond in Winter,” in which the last twelve words are quite as beautiful as the thing they describe:

Standing on the snow-covered plain, as if in a pasture amid the hills, I cut my way first through a foot of snow, and then a foot of ice, and open a window under my feet, where, kneeling to drink, I look down into the quiet parlor of fishes, pervaded by a softened light as through a window of ground glass, with its bright sanded floor the same as in summer; there a perennial waveless serenity reigns as in the amber, twilight sky.

Or, again, this prose poem quoted in Channing’s book:

One more confiding heifer, the fairest of the herd, did by degrees approach as if to take some morsel from our hands, while our hearts leaped to our mouths with expectation and delight. She by degrees drew near with her fair limbs (progressive), making pretence of browsing; nearer and nearer, till there was wafted to us the bovine fragrance, – cream of all the dairies that ever were or will be: and then she raised her gentle muzzle toward us, and snuffed an honest recognition within hand’s reach. I saw it was possible for his herd to inspire with love the herdsman. She was as delicately featured as a hind. Her hide was mingled white and fawn-color, and on her muzzle’s tip there was a white spot not bigger than a daisy; and on her side turned toward me, the map of Asia plain to see.

The following passages fulfill the main tenets of the contemporary Imagists:

I am no more lonely than the loon in the pond that laughs so loud, or than Walden pond itself. What company has that lonely lake, I pray?.. I am no more lonely than a single mullein or dandelion in a pasture, or a bean-leaf, or sorrel, or a horse-fly, or a bumble-bee. I am no more lonely than the Mill Brook, or a weather-cock, or the north star, or the south wind, or an April shower, or a January thaw, or the first spider in a new house.

The wind has gently murmured through the blinds, or puffed with feathery softness against the windows, and occasionally sighed like a summer zephyr, lifting the leaves along, the livelong night. The meadow-mouse has slept in his snug gallery in the sod, the owl has sat in a hollow tree in the depth of the swamp; the rabbit, the squirrel and the fox have all been housed. The watch-dog has lain quiet on the hearth, and the cattle have stood silent in their stalls… But while the earth has slumbered, all the air has been alive with feathery flakes descending, as if some northern Ceres reigned, showering her silvery grain over all the fields.

No yard; but unfenced Nature reaching to your very sills. A young forest growing up under your windows, and wild sumachs and blackberry vines breaking through into your cellar; sturdy pitch-pines rubbing and creaking against the shingles for want of room, their roots reaching quite under the house. Instead of a scuttle or a blind blown off in the gale, – a pine tree torn up by the roots behind your house for fuel. Instead of no path to the front-yard gate in the Great Snow, – no gate – no front yard, and no path to the civilized world.

His manner of writing was so like Emerson’s that the comments on the style of the elder man (see pp. 212–215) apply for the most part to that of the younger.

From the year of “Walden’s” appearance to the end of Thoreau’s life, in 1862, three matters are specially worthy of record. The first is that recognition began at last to come. This probably did not hasten his writing, but it released some of the great accumulation of manuscript in his possession. Several of the magazines accepted his papers, notably The Atlantic Monthly, which took eight of his articles, although seven of them were not published until the two years just after his death. The second is his eager friendship for two of the most strikingly unconventional men of his day – Walt Whitman and John Brown “of Harper’s Ferry.” Of Whitman he wrote, when few were reading him and few of these approving:

I have just read his second edition (which he gave me), and it has done me more good than any reading for a long time… I have found his poems exhilarating, encouraging… We ought to rejoice greatly in him. He occasionally suggests something a little more than human. You can’t confound him with the other inhabitants of Brooklyn or New York. How they must shudder when they read him!.. Since I have seen him, I find I am not disturbed by any brag or egoism in his book. He may turn out the least of a braggart of all, having a better right to be confident.

John Brown he had met in Concord only a few weeks before the Harper’s Ferry raid. Two weeks after the capture of Brown he delivered an address on the issues, first in Concord and later in Worcester and in Boston, defying his friends who advised him to silence. And after the execution of the old Kansan he arranged funeral services in Concord.

It turns what sweetness I have to gall, to hear, or hear of, the remarks of some of my neighbors. When we heard at first that he was dead, one of my townsmen observed that “he died as the fool dieth”; which, pardon me, for an instant suggested a likeness in him dying to my neighbor living… This event advertises me that there is such a fact as death, – the possibility of a man’s dying. It seems as if no man had ever lived before; for in order to die you must first have lived… I hear a good many pretend that they are going to die; or that they have died, for aught that I know. Nonsense! I’ll defy them to do it. They haven’t got life enough in them. They’ll deliquesce like fungi; and keep a hundred eulogists mopping the spot where they left off. Only a half a dozen or so have died since the world began.

The final fact of these later years is the breakdown of his own health. In spite of the moderation and sanity of his out-of-door habits his strength began to fail him before he had reached what should be the prime of life. From the ages of thirty-eight to forty he had to exercise the greatest care, avoiding any heavy exertion. A severe cold caught in 1860 developed soon into consumption, which carried him off in the spring of 1862 at the age of forty-five.

BOOK LIST

Henry David Thoreau. Works. The Riverside Edition. 1894. 10 vols. Walden Edition. 1906. 20 vols. (Of these volumes the last fourteen are the complete Journal, which includes in its original form what stands in Vols. V–VIII of the Riverside Edition, as Early Spring in Massachusetts, Summer, Autumn, Winter.) His works appeared in book form originally as follows: A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, 1849; Walden, 1854; Excursions, 1863; The Maine Woods, 1864; Cape Cod, 1865; Letters to Various Persons, 1865; A Yankee in Canada, 1866; Early Spring in Massachusetts, 1881; Summer, 1884; Winter, 1888; Anti-Slavery and Reform Papers, 1890; Essays and Other Writings, 1891; Autumn, 1892; Miscellanies, 1893; Familiar Letters, 1894; Poems, 1895.

Bibliography

A volume compiled by Francis H. Allen. 1908. Also Cambridge History of American Literature, Vol. II, pp. 411–415.

Biography and Criticism

The standard life is by Frank B. Sanborn. 1917.

Benton, Joel. The Poetry of Thoreau. Lippincot’s, May, 1886.

Burroughs, John. Indoor Studies. 1889.

Channing, W. E. Thoreau, the Poet-Naturalist. 1873.

Emerson, R. W. Lectures and Biographical Sketches. Centenary Edition. 1903.

Foerster, Norman. Humanism of Thoreau. Nation, Vol. CV, pp. 9–12.

Lowell, J. R. My Study Windows. 1871.

Macmechan, Archibald. Cambridge History of American Literature, Vol. II, Bk. II, chap. x.

Marble, A. R. Thoreau: his Home, Friends, and Books. 1902.

More, P. E. Shelburne Essays. Ser. 1. 1904.

Pattee, F. L. American Literature since 1870, chap. viii, sec. I. 1915.

Richardson, C. F. American Literature, Vol. I. 1887.

Salt, H. S. Life of Thoreau. 1890.

Salt, H. S. Literary Sketches. 1888.

Sanborn, F. B. Life of Thoreau. 1882. (A.M.L.Ser.)

Sanborn, F. B. Personality of Thoreau. 1901.

Stevenson, R. L. Familiar Studies of Men and Books. 1882.

Torrey, Bradford. Friends on the Shelf. 1906.

Trent, W. P. American Literature. 1903.

Van Doren, Mark. Henry David Thoreau: a Critical Study. 1916. Pertaining to Thoreau. S. A. Jones, editor. 1901. (Contains ten reprinted magazine articles on Thoreau.)

TOPICS AND PROBLEMS

Read Emerson’s “Woodnotes,” Vol. I, pp. 2 and 3, for a passage which admirably characterizes Thoreau, though it is said to have been written without specific regard to him.

Read “A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers,” noting chiefly either the passages on literature and men of letters or the passages of a sociological interest. Is there a connecting unity in these passages?

Read “Economy” in “Walden” and the second and third of Crèvecœur’s “Letters from an American Farmer” for the contrast in ideas on property or for the contrast in ideas on the privileges and the obligations of citizenship.

Read in “Walden” or “The Maine Woods” or “Cape Cod” or “A Yankee in Canada” or “Excursions” for examples of exaggeration and of aggressive self-consciousness. Is there any real likeness between Thoreau and Whitman in these respects?

Read the characterizations of Thoreau in the essays by Robert Louis Stevenson and James Russell Lowell and decide in which points they should be modified.

Read any one or two essays for Thoreau’s allusions to science and to the sciences, the kind of allusions made, and the kind of significances derived from them.

Read any two or three essays for the nature element in them, the kind of things alluded to, and the kind of significances derived from them.

CHAPTER XVI

NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE

The thought of Hawthorne (1804–1864) as a member of the “Concord group” should be made with a mental reservation. He did not belong to Concord in any literal or figurative sense, he was not an intimate of those who did, he lived there for only seven years at two different periods in his career, and, wherever he lived, he was in thought and conduct anything but a group man. Yet he was a resident there for the first three years after his marriage (1842–1846), and he developed enough of a liking for the town to return to it for the closing four years of his life. What the town was by tradition and what it had become through Emerson’s influence made it the most congenial spot in America for Hawthorne.