полная версия

полная версияThe Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

On the 27th of June the Abolition of the Slave Trade was read a third time in the Commons, and some curious facts came out in debate. One member called attention to the fact that there were 7,000 French prisoners on the Island of Barbadoes, besides a great number in prison-ships, and feared they would foment discontent among the negroes, who did not distinguish between the abolition of the slave trade and immediate emancipation. He also pointed out that the Moravian missionaries on the island were teaching, most forcibly, the fact that all men were alike God’s creatures, and that the last should be first and the first last.

An honourable member immediately replied in vindication of the missionaries, and said that no fewer than 10,000 negroes had been converted in the Island of Antigua, and that their tempers and dispositions had been, thereby, rendered so much better, that they were entitled to an increased value of £10.

Next day the Bill was taken up to the Lords and read for the first time, during which debate the Duke of Clarence said: “Since a very early period of his life, when he was in another line of profession – which he knew not why he had no longer employment in – he had ocular demonstration of the state of slavery, as it was called, in the West Indies, and all that he had seen convinced him that it not only was not deserving of the imputations that had been cast upon it, but that the abolition of it would be productive of extreme danger and mischief.”

Before the second reading he also presented two petitions against it, and when the second reading did come on, on the 3rd of July, Lord Hawkesbury moved that such reading should be on that day three months, and this motion was carried without a division, so that the Bill was lost for that year.

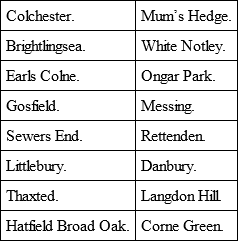

The Invasion Scare, although dying out, in this year was far from dead; but, though people did not talk so much about it, the Government was vigilant and watchful, as was shown by many little matters – notably the signals. In the eastern district of England were 32,000 troops ready to move at a moment’s notice; whilst the hoisting of a red flag at any of the following stations would ensure the lighting of all the beacons, wherever established:

Transport seems to have been the weakest spot in the military organizations, and a Committee sat both at the Mansion House, and Thatched House Tavern, to stimulate the patriotic ardour of owners of horses and carriages, in order that they might offer them for the use of the Government. A large number of job-masters, too, offered to lend their horses, provided their customers would send their coachmen and two days’ forage with them.

There was in this year a very close election for Middlesex, between Sir Francis Burdett and Mr. Mainwaring. The election lasted, as usual, a fortnight, and Sir Francis claimed a majority of one. This so elated his supporters that they formed a triumphal procession from Brentford, the county town, to Piccadilly, composed as under:

A Banner, on orange ground, inscribedVictoryHorsemen, two and twoFlags borne by HorsemenPersons on foot in files of six, singing “Rule, Britannia.”Handbell RingersBody of foot, as beforeCar with Band of MusicLarge Body of HorsemenSir Francis BurdettIn his Chariot, accompanied by his Brother, and anotherGentleman covered with Laurels and drawn bythe Populace, with an allegorical painting ofLiberty and Independence,and surrounded with lighted flambeauxA second Car, with a Musical BandA Body of HorsemenGentlemen’s and other Carriages in a long Cavalcade,which closed the ProcessionWas it not a pity, after all this excitement, that on a scrutiny, the famous majority of one was found to be fallacious, and that Mr. Mainwaring had a majority of five? a fact of which he duly availed himself, sitting for Middlesex at the next meeting of Parliament.

The close of the year is not particularly remarkable for any events other than the arrival in England, on the 1st of November, of the brother of Louis XVIII. (afterwards Charles X.), and the reconciliation which took place between the Prince of Wales, and his royal father, on the 12th of November, which was made the subject of a scathing satirical print by Gillray (November 20th). It is called “The Reconciliation.” “And he arose and came to his Father, and his Father saw him, and had compassion, and ran, and fell on his Neck and kissed him.” The old King is in full Court costume, with brocaded Coat and Ribbon of the Garter, and presents a striking contrast to the tattered prodigal, whose rags show him to be in pitiable case, and who is faintly murmuring, “Against Heaven and before thee.” The Queen, with open arms, stands on the doorstep to welcome the lost one, whilst Pitt and Lord Moira, as confidential advisers, respectively of the King and the Prince, look on with a curious and puzzled air.

Consols were, January 56⅞; December 58⅝; having fallen as low as 54½ in February. The quartern loaf began the year at 9½d. and left off at 1s. 4½d. Average price of wheat 74s.

CHAPTER XII

1805Doings of Napoleon – His letter to George III. – Lord Mulgrave’s reply – War declared against Spain – General Fast – Men voted for Army and Navy – The Salt Duty – Withdrawal of “The Army of England” – Battle of Trafalgar and death of Nelson – General Thanksgiving.

THE YEAR 1805 was uneventful for many reasons, the chief of which was that Bonaparte was principally engaged in consolidating his power after his Coronation. He was elected Emperor on the 20th of May, 1804, but was not crowned until December of the same year. In March, 1805, he was invited by the Italian Republic to be their monarch, and, in April, he and Josephine left Paris for Milan, and in May he crowned himself King of Italy.

He was determined, if only nominally, to hold out the olive branch of peace to England, and on the 2nd of January, 1805, he addressed the following letter to George the Third.

“Sir and Brother, – Called to the throne of France by Providence, and by the suffrages of the senate, the people, and the army, my first sentiment is a wish for peace. France and England abuse their prosperity. They may contend for ages; but do their governments well fulfil the most sacred of their duties, and will not so much blood, shed uselessly, and without a view to any end, condemn them in their own consciences? I consider it as no disgrace to make the first step. I have, I hope, sufficiently proved to the world that I fear none of the chances of war; it, besides, presents nothing that I need to fear: peace is the wish of my heart, but war has never been inconsistent with my glory. I conjure your Majesty not to deny yourself the happiness of giving peace to the world, nor to leave that sweet satisfaction to your children; for certainly there never was a more fortunate opportunity, nor a moment more favourable, to silence all the passions and listen only to the sentiments of humanity and reason. This moment once lost, what end can be assigned to a war which all my efforts will not be able to terminate? Your Majesty has gained more within the last ten years both in territory and riches than the whole extent of Europe. Your nation is at the highest point of prosperity: to what can it hope from war? To form a coalition with some Powers of the Continent! The Continent will remain tranquil – a coalition can only increase the preponderance and continental greatness of France. To renew intestine troubles? The times are no longer the same. To destroy our finances? Finances founded on flourishing agriculture can never be destroyed. To take from France her colonies? The Colonies are to France only a secondary object; and does not your Majesty already possess more than you know how to preserve? If your Majesty would but reflect, you must perceive that the war is without an object, without any presumable result to yourself. Alas! what a melancholy prospect to cause two nations to fight merely for the sake of fighting. The world is sufficiently large for our two nations to live in it, and reason is sufficiently powerful to discover means of reconciling everything, when the wish for reconciliation exists on both sides. I have, however, fulfilled a sacred duty, and one which is precious to my heart. I trust your Majesty will believe in the sincerity of my sentiments, and my wish to give you every proof of it.

“Napoleon.”When the King opened Parliament on the 15th of January, 1805, he referred to this letter thus: “I have recently received a communication from the French Government, containing professions of a pacific disposition. I have, in consequence, expressed my earnest desire to embrace the first opportunity of restoring the blessings of peace on such grounds as may be consistent with the permanent safety and interests of my dominions; but I am confident you will agree with me that those objects are closely connected with the general security of Europe.”

The reply of Lord Mulgrave (who had succeeded Lord Harrowby as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs) was both courteous and politic. It was dated the 14th of January, and was addressed to M. Talleyrand.

“His Britannic Majesty has received the letter which has been addressed to him by the head of the French Government, dated the 2nd of the present month. There is no object which His Majesty has more at heart, than to avail himself of the first opportunity to procure again for his subjects the advantages of a peace, founded on bases which may not be incompatible with the permanent security and essential interests of his dominions. His Majesty is persuaded that this end can only be attained by arrangements which may, at the same time, provide for the future safety and tranquillity of Europe, and prevent the recurrence of the dangers and calamities in which it is involved. Conformably to this sentiment, His Majesty feels it is impossible for him to answer more particularly to the overture that has been made him, till he has had time to communicate with the Powers on the Continent, with whom he is engaged with confidential connexions and relations, and particularly the Emperor of Russia, who has given the strongest proofs of the wisdom and elevation of the sentiments with which he is animated, and the lively interest which he takes in the safety and independence of the Continent.

“Mulgrave.”Very shortly after this, England declared war against Spain, and the Declaration was laid before Parliament on January 24th. A long discussion ensued thereon; but the Government had a majority on their side of 313 against 106.

Probably, His Majesty’s Government had some inkling of what was coming, for on the 2nd of January was issued a proclamation for another general Fast, which was to take place on the 20th of February, “for the success of His Majesty’s arms.” History records that the Volunteers went dutifully to church; and also that “a very elegant and fashionable display of equestrians and charioteers graced the public ride about three o’clock. The Countesses of Cholmondeley and Harcourt were noticed for the first time this season, each of whom sported a very elegant landau. Mr. Buxton sported his four bays in his new phaeton, in a great style, and Mr. Chartres his fine set of blacks.” Thus showing that different people have different views of National Fasting and Chastening.

That the arm of the flesh was also relied on, is shown by the fact that Parliament in January voted His Majesty 120,000 men, including marines, for his Navy; and in February 312,048 men for his Army, with suitable sums for their maintenance and efficiency.

Of course this could not be done without extra taxation, and the Budget of the 18th of February proposed – an extra tax of 1d., 2d., and 3d. respectively on single, double, and treble letters (as they were called) passing through the post; extra tax of 6d. per bushel on salt, extra taxes on horses, and on legacies. All these were taken without much demur, with one exception, and that was the Salt Duty Bill. Fierce were the squabbles over this tax, and much good eloquence was expended, both in its behalf and against it, and it had to be materially altered before it was passed; one of the chief arguments against it being that it would injuriously affect the fisheries, as large quantities were used in curing. But a heavy tax on salt would also hamper bacon and ham curing, &c., and Mrs. Bull had an objection to see Pitt as

The Flotilla could not sail, and “the Army of England” was inactive, when circumstances arose that rendered the withdrawal of the latter imperative: consequently the Flotilla was practically useless, for it had no troops to transport. Austria had gone to war with France without the formality of a Declaration, and the forces of the Allies were computed at 250,000. The French troops were reckoned at 275,000 men, but “the Army of England” comprised 180,000 of these, and they must needs be diverted to the point of danger.

We can imagine the great wave of relief that spread over the length and breadth of this land at this good news. The papers were, of course, most jubilant, and the whole nation must have felt relieved of a great strain. Even the Volunteers must have got somewhat sick of airing and parading their patriotism, with the foe within tangible proximity, and must have greatly preferred its absence.

The Times is especially bitter on the subject:

“1. The scene that now opens upon the soldiers of France, by being obliged to leave the coast, and march eastwards, is sadly different from that Land of Promise which, for two years, has been held out to them, in all sorts of gay delusions. After all the efforts of the Imperial Boat Builder, instead of sailing over the Channel, they have to cross the Rhine. The bleak forests of Suabia will make but a sorry exchange for the promised spoils of our Docks and Warehouses. They will not find any equivalent for the plunder of the Bank, in another bloody passage through ‘the Valley of Hell;’ but they seem to have forgotten the magnificent promise of the Milliard.”21

The Times (September 13th) quoting from a French paper, shows that they endeavoured to put a totally different construction on the withdrawal of their troops, or rather to make light of it. “Whilst the German papers, with much noise, make more troops march than all the Powers together possess, France, which needs not to augment her forces, in order to display them in an imposing manner, detaches a few thousand troops from the Army of England, to cover her frontiers, which are menaced by the imprudent conduct of Austria. England is preparing fresh victories for us, and for herself fresh motives for decrying her ambition. After all, those movements are not yet a certain sign of war,” &c.

The greatest loss the English Nation sustained this year, was the death of Admiral Lord Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar, which was fought on the 21st of October, 1805.

On the 6th of November the glorious news of the Victory was published, and there was but one opinion – that it was purchased too dearly. That evening London was but partially illuminated. On the 7th these symptoms of rejoicing were general, but throughout them there was a sombre air – a mingling of the cypress with the laurel, and men went about gloomily, thinking of the dead hero: at least most did – some did not; even of those who might have worn a decent semblance of woe – old sailors – some of whom, according to the Times, behaved in a somewhat unseemly manner. “A squadron of shattered tars were drawn up in line of battle, opposite the Treasury, at anchor, with their lights aloft, all well stowed with grog, flourishing their mutilated stumps, cheering all hands, and making the best of their position, in collecting prize money.”

A General Thanksgiving for the Victory was proclaimed to take place on the 5th of December. The good Volunteers were duly marched to church, and one member of the Royal Family – the Duke of Cambridge – actually attended Divine Worship on the occasion. At Drury Lane Theatre, “the Interlude of The Victory and Death of Lord Nelson seemed to affect the audience exceedingly; but the tear of sensibility was wiped away by the merry eccentricities of The Weathercock” – the moral to be learned from which seems to be, that the good folks of the early century seemed to think that God should not be thanked, nor heroes mourned, too much. This must close this year, for Nelson’s funeral belongs to the next.

After the Battle of Trafalgar, the Patriotic Fund was again revived, and over £50,000 subscribed by the end of the year.

Consols were remarkably even during this year, varying very little even at the news of Trafalgar: January, 61⅞; December, 65.

The quartern loaf varied from January 1s. 4¼d., to December 1s. 0¼d.

Wheat varied from 95s. to 90s. per quarter.

CHAPTER XIII

1806Nelson’s funeral – Epigrams – Death of Pitt – His funeral – General Fast – Large coinage of copper – Impeachment of Lord Melville – The Abolition of the Slave Trade passes the House of Commons – Death and funeral of Fox – His warning Napoleon of a plot against him – Negotiations for peace – Napoleon declares England blockaded.

THE YEAR opens with the Funeral of Nelson, whose Victory at Trafalgar had made England Mistress of the Ocean. He was laid to his rest in St Paul’s on January 9th, much to the profit of the four vergers of that Cathedral, who are said to have made more than £1000, by the daily admission of the throngs desirous of witnessing the preparations for the funeral. The Annual Register says, “The door money is taken as at a puppet show, and amounted for several days to more than forty pounds a day.” Seats to view the procession, from the windows of the houses on the route, commanded any price, from One Guinea each; and as much as Five Hundred Guineas is said to have been paid for a house on Ludgate Hill.22

Enthusiasm was at its height, as it was in later times, within the memory of many of us, when the Duke of Wellington came to rest under the same roof as the Gallant Nelson. His famous signal – which, even now, thrills the heart of every Englishman – was prostituted to serve trade Advertisements, vide the following: “England expects every man to do his duty. Nelson’s Victory, or Twelfth Day. To commemorate that great National Event, which is the pride of every Englishman to hand down to the latest posterity, as well as to contribute towards alleviating the sufferings of our brave wounded Tars, &c., H. Webb, Confectioner, Little Newport Street, will, on that day, Cut for Sale, the Largest Rich Twelfth Cake ever made, weighing near 600 lbs., part of the profits of which H. W. intends applying to the Patriotic Fund at Lloyd’s.”23

His body lay in State at Greenwich in the “Painted Hall” (then called the “Painted Chamber”) from Sunday the 5th of January until the 8th. Owing to Divine Service not being finished, a written notice was posted up, that the public could not be admitted until 11. a.m.; by which time many thousands of people were assembled. Punctually at that hour, the doors were thrown open, and, though express orders had been given that only a limited number should be admitted at once, yet the mob was so great as to bear down everything in its way. Nothing could be heard but shrieks and groans, as several persons were trodden under foot and greatly hurt. One man had his right eye literally torn out, by coming into contact with one of the gate-posts. Vast numbers of ladies and gentlemen lost their shoes, hats, shawls, &c., and the ladies fainted in every direction.

The Hall was hung with black cloth, and lit up with twenty-eight Silver Sconces, with two wax candles in each – a light which, in that large Hall, must have only served to make darkness visible. High above the Coffin hung a canopy of black velvet festooned with gold, and by the coffin was the Hero’s Coronet. Shields of Arms were around, and, at back, was a trophy, which was surmounted by a gold shield, encircled by a wreath having upon it “Trafalgar” in black letters.

The bringing of the body from Greenwich to Whitehall by water, must have been a most impressive sight – and one not likely to be seen again, owing to the absence of rowing barges. That which headed the procession bore the Royal Standard, and carried a Captain and two Lieutenants in full uniform, with black waistcoats, breeches, and stockings, and crape round their hats and arms.

In the second barge were the Officers of Arms, bearing the Shield, Sword, Helm, and Crest, of the deceased, and the great banner was borne by Captain Moorsom, supported by two lieutenants.

The third barge bore the body, and was rowed by forty-six men from Nelson’s flag-ship the Victory. This barge was covered with black velvet, and black plumes, and Clarencieux King-at-Arms sat at the head of the coffin, bearing a Viscount’s Coronet, upon a black velvet cushion.

In the fourth barge came the Chief Mourner, Admiral Sir Peter Parker, with many assistant Mourners and Naval grandees.

Then followed His Majesty’s barge, that of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, the Lord Mayor’s barge, and many others; and they all passed slowly up the silent highway, to the accompaniment of minute guns, the shores being lined with thousands of spectators, every man with uncovered head. All traffic on the river was suspended, and the deck, yards, masts, and rigging of every vessel were crowded with men.

The big guns of the Tower boomed forth, and similar salutes accompanied the mournful train to Whitehall, from whence the body was taken, with much solemnity, to the Admiralty, there to lie till the morrow.

His resting-place was not fated to be that of his choice. “Victory, or Westminster Abbey,” he cried, forgetful that the Nation had apportioned the Abbey to be the Pantheon of Genius, and St. Paul’s to be the Valhalla of Heroes – and to the latter he was duly borne.

I refrain from giving the programme of the procession, because of its length, which may be judged by the fact, that the first part left the Admiralty at 11 a.m., and the last of the mourning coaches a little before three. The Procession may be divided into three parts: the Military, the funeral Pageant proper, and the Mourners. There were nearly 10,000 regular soldiers, chiefly composed of those who had fought in Egypt, and knew of Nelson; and this was a large body to get together, when the means of transport were very defective – a great number of troops in Ireland, and a big European War in progress, causing a heavy drain upon the Army. The Pageant was as brave as could be made, with pursuivants and heralds, standards and trumpets, together with every sort of official procurable, and all the nobility, from the younger sons of barons, to George Prince of Wales, who was accompanied by the Dukes of Clarence and Kent. The Dukes of York and Cambridge headed the Procession, and the Duke of Sussex made himself generally useful by first commanding his regiment of Loyal North Britons, and then riding to St. Paul’s on his chestnut Arabian. The Mourners, besides the relatives of the deceased, consisted of Naval Officers, according to their rank – the Seniors nearest the body; and, to give some idea of the number of those who followed Nelson to the grave, there were one hundred and eighty-four Mourning Coaches, which came after the Body, which was carried on a triumphal car, fashioned somewhat after his flag-ship the Victory– the accompanying illustration of which I have taken from the best contemporary engraving I could find.

The whole of the Volunteer Corps of the Metropolis, and its vicinity, were on duty all day, to keep the line of procession.

At twenty-three and a half minutes past five the coffin containing Nelson’s mortal remains was lowered into its vault. Garter King-at-Arms had pronounced his style and duly broken his staff, and then the huge procession, which had taken so much trouble and length of time to prepare, melted, and each man went his way; the car being taken to the King’s Mews, where it remained for a day or two, until it was removed to the grand hall at Greenwich – and the Hero, or rather his grave, was converted into a sight for which money was taken.

“EPIGRAM,ON THE SHAMEFUL EXHIBITION AT ST. PAUL’SBrave Nelson was doubtless a lion in war,With terror his enemies filling;But now he is dead, they are safe from his paw,And the Lion is shewn for a shilling.”24“THE INVITATIONLo! where the relics of brave Nelson lie!And, lo! each heart with saddest sorrow weeping!Come then, ye throng, and gaze with anxious eye —But, ah! remember, you must —pay for peeping.”25The cost of this funeral figures, in the expenses of the year, at £14,698 11s. 6d.