полная версия

полная версияThe Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

CHAPTER V

1801The Union with Ireland – Proclamations thereon – Alteration of Great Seal – Irish Member called to order (footnote) – Discovery of the Planet Ceres – Proclamation of General Fast – High price of meat, and prosperity of the farmers – Suffering of the French prisoners – Political dissatisfaction – John Horne Tooke – Feeding the French prisoners – Negotiations for Peace – Signing preliminaries – Illuminations – Methods of making the news known – Ratification of preliminaries – Treatment of General Lauriston by the mob – More Illuminations – Manifestation of joy at Falmouth – Lord Mayor’s banquet.

“LE ROI EST mort. Vive le Roi.” Ring the bells to welcome the baby Nineteenth Century, who is destined to utterly eclipse in renown all his ancestors.

Was it for good, or was it for evil, that its first act should be that of the Union with Ireland? It was compulsory, for it was a legacy bequeathed it. There were no national rejoicings. The new Standard was hoisted at the Tower, and at St. James’s, the new “Union” being flown from St. Martin’s steeple, and the Horse Guards; and, after the King and Privy Council had concluded the official recognition of the fact, both the Park and Tower guns fired a salute. The ceremonial had the merit, at least, of simplicity.

A long Royal Proclamation was issued, the principal points of which were: “We appoint and declare that our Royal Stile and Titles shall henceforth be accepted, taken, and used, as the same are set forth in manner and form following; that is to say, the same shall be expressed in the Latin tongue by these words, ‘GEORGIUS TERTIUS, Dei Gratiâ, Britanniarum Rex, Fidei Defensor.’ And in the English tongue by these words, ‘GEORGE the THIRD, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith.’ And that the Arms or ensigns armorial of the said United Kingdom shall be quarterly – first and fourth, England; second, Scotland; third, Ireland; and it is our will and pleasure, that there shall be borne therewith, on an escocheon of pretence, the Arms of our dominions in Germany, ensigned with the Electoral bonnet. And it is our will and pleasure that the Standard of the said United Kingdom shall be the same quartering as are herein before declared to be the arms or ensigns armorial of the said United Kingdom, with the escocheon of pretence thereon, herein before described: and that the Union flag shall be azure, the Crosses-saltires of St. Andrew and St. Patrick quarterly per saltire countercharged argent and gules; the latter fimbriated of the second; surmounted by the Cross of St. George of the third, fimbriated as the saltire.” There is a curious memorial of these arms to be seen in a stained-glass window in the church of St. Edmund, King and Martyr, Lombard Street, which window was put up as a memento of the Union. In the above arms it is to be noticed that the fleur de lys, so long used as being typical of our former rule in France, is omitted. A new Great Seal was also made – the old one being defaced.12 On January 1, 1801, the King issued a proclamation for holding the first Parliament under the Union, declaring that it should “on the said twenty-second day of January, one thousand, eight hundred and one, be holden, and sit for the dispatch of divers weighty and important affairs.”

On the 1st of January, also, was a proclamation issued, altering the Prayer-book to suit the change, and, as some readers would like to know these alterations, I give them.

“In the Book of Common Prayer, Title Page, instead of ‘The Church of England,’ put ‘of the United Church of England and Ireland.’

“Prayer for the High Court of Parliament, instead of Our Sovereign, and his Kingdoms,’ read ‘and his Dominions.’

“The first Prayer to be used at sea, instead of ‘His Kingdoms,’ read ‘His Dominions.’

“In the form and manner of making, ordaining, and consecrating of Bishops, Priests, and Deacons, instead of the order ‘of the Church of England,’ read ‘of the United Church of England and Ireland.’

“In the preface of the said form, in two places, instead of ‘Church of England,’ read ‘in the United Church of England and Ireland.’

“In the first question in the Ordination of Priests, instead of ‘Church of England,’ read ‘of this United Church of England and Ireland.’

“In the Occasional Offices, 25th of October, the King’s accession, instead of ‘these realms,’ read ‘this realm.’

“In the Collect, before the Epistle, instead of ‘these Kingdoms,’ read ‘this United Kingdom.’

“For the Preachers, instead of ‘King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland,’ say, ‘King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.’”

The Union gave seats in the Imperial Parliament to one hundred commoners, twenty-eight temporal peers, who were elected for life, and four bishops representing the clergy, taking their places in rotation.13

The heavens marked the advent of the New Century by the discovery, by the Italian astronomer Piazzi, of the Planet Ceres on the 1st of January; and, to begin the year in a proper and pious manner, a proclamation was issued that a general fast was to be observed in England and Ireland, on the 13th, and in Scotland, on the 12th of February.

The cry of scarcity of food still continued; wheat was mounting higher and higher in price. In January it was 137s. a quarter, and it rose still higher. The farmers must have had a good time of it, as the Earl of Warwick declared in Parliament (November 14, 1800), they were making 200 per cent. profit. “Those who demanded upwards of 20s. a bushel for their corn, candidly owned that they would be contented with 10s. provided other farmers would bring down their prices to that standard.” And again (17th of November) he said: “He should still contend that the gains of the farmer were enormous, and must repeat his wish, that some measure might be adopted to compel him to bring his corn to market, and to be contented with a moderate profit. He wondered not at the extravagant style of living of some of the farmers, who could afford to play guinea whist, and were not contented with drinking wine only, but even mixed brandy with it; on farms from which they derived so much profit, they could afford to leave one-third of the lands they rented wholly uncultivated, the other two-thirds yielding them sufficient gain to support all their lavish expenditure.”

Still the prosperity of the farmer must have been poor consolation to those who were paying at the rate of our half-crown for a quartern loaf, so that it is no wonder that the authorities were obliged to step in, and decree that from January 31, 1801, the sale of fine wheaten bread should be forbidden, and none used but that which contained the bran, or, as we should term it, brown, or whole meal, bread.

The poor French prisoners, of course, suffered, and were in a most deplorable condition, more especially because the French Government refused to supply them with clothes. They had not even the excuse that they clothed their English prisoners, for our Government looked well after them in that matter, however much they may have suffered in other ways.

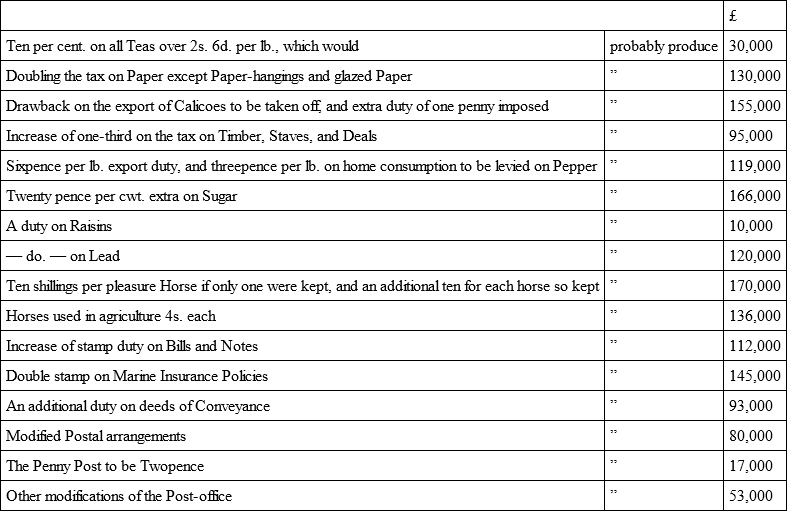

On the 18th of February Pitt opened his budget, and as an increase was needed of over a million and three quarters, owing to the war, and interest of loan, new taxes were proposed as follows:

There had been political dissatisfactions for some time past, which was dignified with the name of sedition, but the malcontents were lightly dealt with. On the 2nd of March those who had been confined in the Tower and Tothill Fields were liberated on their own recognizances except four – Colonel Despard, Le Maitre, Galloway, and Hodgson, who, being refused an unconditional discharge, preferred to pose as martyrs, and were committed to Tothill Fields. Of Colonel Despard we shall have more to say further on. Vinegar Hill had not been forgotten in Ireland, and sedition, although smothered, was still alight, so that an Act had to be introduced, prolonging the suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act in that kingdom.

In this year, too, was brought in a Bill which became law, preventing clergymen in holy orders from sitting in the House of Commons. This was brought about by the election (this sessions) of the Rev. John Horne Tooke for Old Sarum, a rotten borough, which in 1832 was disfranchised, as it returned two members, and did not have very many more voters. Tooke had been a partizan of Wilkes, and belonged, as we should now term it, to the Radical party, a fact which may probably have had something to do with the introduction of the Bill, as there undoubtedly existed an undercurrent of dissatisfaction, which was called sedition. Doubtless societies of the disaffected existed, and a secret commission, which sat for the purpose of exposing them, reported, on the 27th of April, that an association for seditious purposes had been formed under the title of United Britons, the members whereof were to be admitted by a test.

The question of feeding the French prisoners of war again turned up, and as it was not well understood, the Morning Post, 1st of September, 1801, thus explains matters: “Much abuse is thrown out against the French Government for not providing for the French prisoners in this country. We do not mean to justify its conduct; but the public should be informed how the question really stands. It is the practice of all civilized nations to feed the prisoners they take. Of course the French prisoners were kept at the expense of the English Government till, a few years ago, reports were circulated of their being starved and ill-treated. The French Government, in hopes of stigmatizing the English Ministry as guilty of such an enormous offence, offered to feed the French prisoners here at its own expense; a proposal, which was readily accepted, as it saved much money to this country; but the French Government has since discontinued its supplies, and thus paid a compliment to our humanity at the expense of our purse. In doing this, however, France has only reverted to the established practice of war, and all the abuse of the Treasury journals for withholding the supplies to the French prisoners, only betrays a gross ignorance of the subject.”

Of their number, the Morning Post, 16th of October, 1801, says, “The French prisoners in this country at present amount to upwards of 20,000, and they are all effective men, the sick having been sent home from time to time as they fell ill. Of these 20,000 men, nine out of ten are able-bodied seamen; they are the best sailors of France, the most daring and enterprising, who have been mostly employed in privateers and small cruisers.” Some of them had been confined at Portsmouth for eight years!

M. Otto, in spite of the rebuff he had experienced, the former negotiations for peace having been broken off, was still in London, where he acted as Commissary for exchange of prisoners. Napoleon was making treaties of peace all round, and, if it were to be gained in an honourable manner, it would be good also for England. So Lord Hawkesbury, who was then Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, entered into communication with M. Otto, on the 21st of March, signifying the King’s desire to enter into negotiations for peace, and they went on all the summer. Of course all did not go smoothly, especially with regard to the liberty of the English press, which Napoleon cordially hated, and wished to see repressed and fettered; but this, Lord Hawkesbury either would not, or dared not, agree to. The public pulse was kept in a flutter by the exchange of couriers between England and France, and many were the false rumours which caused the Stocks to fluctuate. Even a few days before the Preliminaries were signed, a most authentic report was afloat that all negotiations were broken off; so we may imagine the universal joy when it was proclaimed as an authentic fact.

It fairly took the Ministry by surprise when, on Wednesday, the 30th of September, an answer was received from Napoleon, accepting the English proposals. Previously, the situation had been very graphically, if not very politely, described in a caricature by Roberts, called “Negotiation See-saw,” where Napoleon and John Bull were represented as playing at that game, seated on a plank labelled, “Peace or War.” Napoleon expatiates on the fortunes of the game: “There, Johnny, now I’m down, and you are up; then I go up, and you go down, Johnny; so we go on.” John Bull’s appreciation of the humour of the sport is not so keen; he growls, “I wish you would settle it one way or other, for if you keep bumping me up and down in this manner, I shall be ruined in Diachilem Plaster.”

But when the notification of acceptance did arrive, very little time was lost in clinching the agreement. A Cabinet Council was held, and an express sent off to the King, whose sanction returned next afternoon. The silver box, which had never been used since the signature of peace with America, was sent to the Lord Chancellor at 5 p.m. for the Great Seal, and his signature; and, the consent of the other Cabinet Ministers being obtained, at 7 p.m. Lord Hawkesbury and M. Otto signed the Preliminaries of Peace in Downing Street, and his lordship at once despatched the following letter, which must have gladdened the hearts of the citizens, to the Lord Mayor.

“TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE THE LORD MAYOR“Downing Street, Oct. 1, 1801, at night.“My Lord,

“I have great satisfaction in informing your Lordship that Preliminaries of Peace between Great Britain and France have been signed this evening by myself, on the part of His Majesty, and by M. Otto, on the part of the French Government. I request your Lordship will have the goodness to make this intelligence immediately public in the City.

“I have the honour to be, &c.,“(Signed) Hawkesbury.”The Lord Mayor was not at the Mansion House, and the messenger had to proceed to his private house at Clapham. His lordship returned to town, and by nine o’clock the good news was known all over London. The Lord Mayor read the letter at the Stock Exchange, and also at Lloyd’s Coffee House, at the bar of which it was afterwards posted; for Lloyd’s was then a great power in the City, from which all public acts, subscriptions, &c., emanated, as was indeed but right, as it was the assembly which embraced all the rich and influential merchants.

Among this class all was joy, and smiles, and shaking of hands. The Three per Cents., which only the previous day were at 59½ rose to 66, and Omnium, which had been at 8, rose to 18.

The news came so suddenly, that the illuminations on the night of the 2nd of October were but very partial. We, who are accustomed to brilliant devices in gas, with coruscating crystal stars, and transparencies, would smile at the illuminations of those days. They generally took the shape of a wooden triangle in each window-pane, on which were stuck tallow candles, perpetually requiring snuffing, and guttering with every draught; or, otherwise, a black-painted board with a few coloured oil-lamps arranged in the form of a crown, with G. R. on either side.

As is observed in the Morning Post of the 3rd October, 1884: “The sensation produced yesterday among the populace was nothing equal to what might have been expected. The capture of half a dozen men-of-war, or the conquest of a colony, would have been marked with a stronger demonstration of joy. The illumination, so far from being general, was principally confined to a few streets – the Strand, the Haymarket, Pall Mall, and Fleet Street. In the last the Globe Tavern was lighted up at an early hour, with the word Peace in coloured lamps. This attracted a considerable mob, which filled the street before the door. It was apprehended that they would immediately set out on their tour through the whole town, and enforce an universal illumination. This induced a few of the bye-streets to follow the example, but nothing more. There were several groups of people, but no crowd, in the neighbourhood of Temple Bar. The other streets, even those that were illuminated, were not more frequented than usual. St. James’s Street, Bond Street, and the west part of the town; east of St. Paul’s, together with Holborn, and the north part, did not illuminate. Several flags were hoisted in the course of the day, and the bells of all the churches were set a-ringing.”

To us, who are accustomed to have our news reeled out on paper tapes hot and hot from the telegraph, or to converse with each other, by means of the telephone, many miles apart, the method used to disseminate the news of the peace throughout the country, seems to be very primitive, and yet no better, nor quicker mode, could have been devised in those days. The mail coaches were placarded PEACE WITH FRANCE in large capitals, and the drivers all wore a sprig of laurel, as an emblem of peace, in their hats.

The Preliminaries of Peace were ratified in Paris on the 5th of October, but General Lauriston, who was to be the bearer of this important document, did not set out from Paris until the evening of the 7th, having been kept waiting until a magnificent gold box, as a fitting shrine for so precious a relic, was finished; and he did not land at Dover until Friday evening, the 9th of October, about 9 p.m. He stayed a brief time at the City of London Inn, Dover, to rest and refresh himself, sending forward a courier, magnificently attired in scarlet and gold, to order horses on the road, and to apprise M. Otto of his arrival. He soon followed in a carriage, with the horses and driver bedecked with blue ribands, on which was the word PEACE. Of course the mob surrounded him, and cheered and yelled as if mad – indeed they must have been, for they actually shouted “Long live Bonaparte!” At M. Otto’s house, the general was joined by that gentleman, who was to accompany him to Reddish’s Hotel, in Bond Street. In Oxford Street, however, the mob took the horses out of his carriage, and drew him to the hotel, rending the air with shouts of joy; some amongst them even mounting a tricoloured cockade. From the hotel window General Lauriston scattered a handful of guineas among his friends, the mob, who afterwards, when he went to Lord Hawkesbury’s office, once more took out the horses, and dragged him from St. James’s Square to Downing Street.

At half-past two the Park guns boomed forth the welcome news, and at three the Tower guns proclaimed the fact to the dwellers in the City, and the East end of London.

It was in vain that the general’s carriage was taken round to a back entrance; the populace were not to be baulked of their amusement, and, on his coming out, the horses were once more detached, men took their places, and he was dragged as far as the Admiralty. Here he remained some time, and was escorted to his carriage by Earl St. Vincent. Said he to the mob, “Gentlemen! gentlemen!” (three huzzas for Earl St. Vincent) “I request of you to be careful, and not overturn the carriage.” The populace assured his lordship they would be careful of, and respectful to, the strangers; and away they dragged the carriage, with shouts, through St. James’s Park, round the Palace, by the Stable-yard, making the old place ring with their yells, finally landing the general uninjured at his hotel.

At night the illuminations were very fine, and there were many transparencies, one or two of which were, to say the least, peculiar. One in Pall Mall had a flying Cupid holding a miniature of Napoleon, with a scroll underneath, “Peace and Happiness to Great Britain.” Another opposite M. Otto’s house, in Hereford Street, Oxford Street, had a transparency of Bonaparte, with the legend, “Saviour of the Universe.” Guildhall displayed in front, a crown and G. R., with a small transparency representing a dove, surrounded with olive. The Post Office had over 6,000 lamps. The India House was brilliant with some 1,700 lamps, besides G. R. and a large PEACE. The Mansion House looked very gloomy. G. R. was in the centre, but one half of the R was broken. The pillars were wreathed with lamps. The Bank only had a double row of candles in front.

Squibs, rockets, and pistols were let off in the streets, and the noise would probably have continued all night, had not a terrible thunder-storm cleared the streets about 11 p.m.

On the 12th, the illuminations were repeated with even more brilliancy, and all went off well. One effect of the peace, which could not fail to be gratifying to all, was the fact, that wheat fell, next marketday, some 10s. to 14s. per quarter.

The popular demonstrations of joy occasionally took odd forms, for it is recorded that at Falmouth, not only the horses, but the cows, calves, and asses were decorated with ribands, in celebration of the peace; and a publican at Lambeth, who had made a vow that whenever peace was made, he would give away all the beer in his cellar, actually did so on the 13th of October.

As was but natural, the Lord Mayor’s installation, on the 9th of November, had a peculiar significance. The Show was not out of the way, at least nothing singular about it is recorded, except the appearance of a knight in armour with his page at the corner of Bride Lane, Bridge Street, had anything to do with it; probably he was only an amateur, as he does not seem to have joined the procession. In the Guildhall was a transparency of Peace surrounded by four figures, typical of the four quarters of the globe returning their acknowledgments for the blessings showered upon them. There were other emblematic transparencies, but the contemporary art critic does not speak very favourably of them. M. Otto and his wife, an American born at Philadelphia, were the guests of the evening, even more than the Lord Chancellor, and the usual ministerial following.

Bread varied in this year from 1s. 9¼d. on the 1st of January to 1s. 10½d. on the 5th of March, 10¼d. on the 12th of November, and 1s. 0¼d. on the 31st of December. Anent the scarcity of wheat at the commencement of the year, there is a singular item to be found in the “Account of Moneys advanced for Public Services from the Civil List (not being part of the ordinary expenditure of the Civil List),” of a “grant of £500 to Thomas Toden, Esq., towards enabling him to prosecute a discovery made by him, of a paste as a substitute for wheat flour.”

Wheat was on January 1st, 137s. per quarter; it reached 153s. in March; and left off on the 31st of December at 68s.

The Three per Cents. varied from 54 on the 1st of January, to 68 on the 31st of December.

CHAPTER VI

1802Disarmament and retrenchment – Cheaper provisions – King applied to Parliament to pay his debts – The Prince of Wales claimed the revenues of the Duchy of Cornwall – Parliament pays the King’s debts – Abolition of the Income Tax – Signature of the Treaty of Amiens – Conditions of the Treaty – Rush of the English to France – Visit of C. J. Fox to Napoleon – Liberation of the French prisoners of war.

THE year 1802 opened somewhat dully, or, rather, with a want of sensational news. Disarmament, and retrenchment, were being carried out with a swiftness that seemed somewhat incautious, and premature. But the people had been sorely taxed, and it was but fitting that the burden should be removed at the earliest opportunity.

Provisions fell to something like a normal price, directly the Preliminaries of Peace were signed, and a large trade in all sorts of eatables was soon organized with France, where prices ruled much lower than at home. All kinds of poultry and pigs, although neither were in prime condition, could be imported at a much lower rate than they could be obtained from the country.

Woodward gives an amusing sketch of John Bull enjoying the good things of this life, on a scale, and at a cost, to which he had long been a stranger.

On the 10th of February the Right Hon. Charles Abbot, afterwards Lord Colchester, was elected Speaker to the House of Commons, in the room of the Right Hon. John Nutford, who had accepted the position of Chancellor of Ireland; and, on the 15th of February, Mr. Chancellor Addington presented the following message from the King:

“George R“His Majesty feels great concern in acquainting the House of Commons that the provision made by Parliament for defraying the expenses of his household, and civil government, has been found inadequate to their support. A considerable debt has, in consequence, been unavoidably incurred, an account of which he has ordered to be laid before this House. His Majesty relies with confidence on the zeal and affection of his faithful Commons, that they will take the same into their early consideration, and adopt such measures as the circumstances may appear to them to require.